The Red Diamond, by Samuel Scoville, jr. (1924, 1925)

[front cover, with spine]

-----

[frontispiece]

Inch by inch the tiger stole down the branch

-----

[title page]

RED DIAMOND

BY

SAMUEL SCOVILLE, JR.

Author of “Boy Scouts in the Wilderness,” “The Blue Pearl,” “The Inca Emerald,” etc., etc.

THE CENTURY CO.

New York & London

-----

[copyright page]

Copyright, 1924, 1925, by THE CENTURY CO. ------- COPYRIGHT, 1925, BY SAMUEL SCOVILLE, JR.

-----

[dedication]

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO

MY DEAR, DEAR BOY

HENRY

WHO URGED ME TO WRITE IT

BUT WHO COULD NOT STAY TO READ IT

-----

[blank page]

-----

[table of contents]

CONTENTS

CHAPTER PAGE

I AMBOYNA … 3

II THE FAR EAST … 29

III THE CLOUDED TIGER … 61

IV THE TALKING TREES … 90

V THE KING COBRA … 119

VI THE WILD MAN OF THE WOODS … 145

VII THE MASAI … 167

VIII THE DEMON OF THE JUNGLE … 194

IX BIRDS OF HEAVEN … 223

X TROBIAND … 246

XI THE TALISMAN … 274

XII THE RED DIAMOND … 302

-----

[blank page]

-----

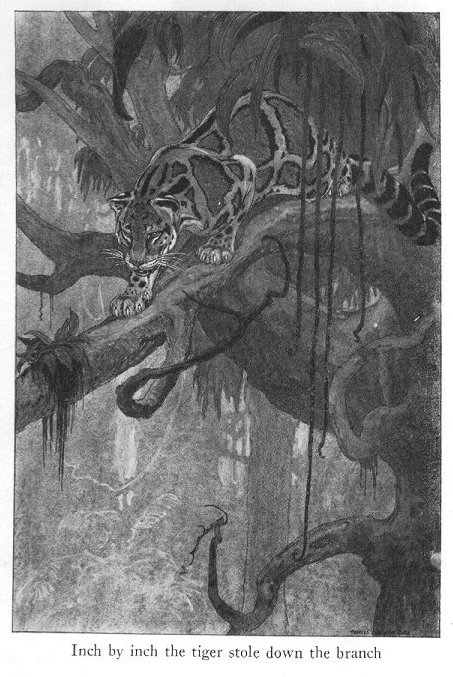

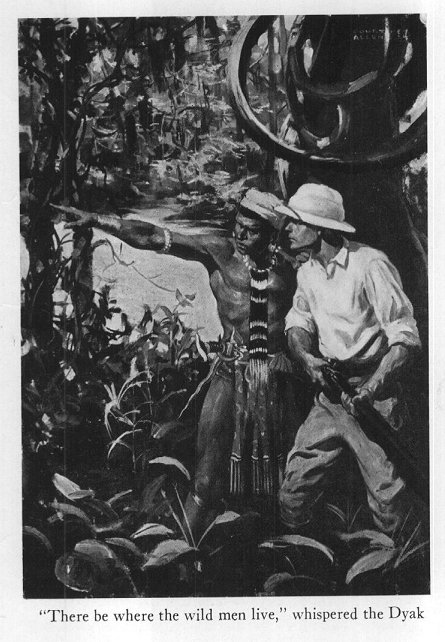

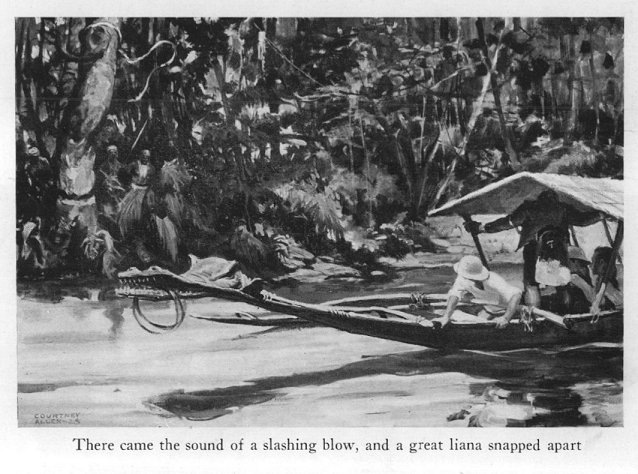

[table of illustrations]

FACING PAGE

Inch by inch the tiger stole down the branch … Frontispiece

“There be where the wild men live,” whispered the Dyak … 146

There came the sound of a slashing blow, and a great liana snapped apart … 200

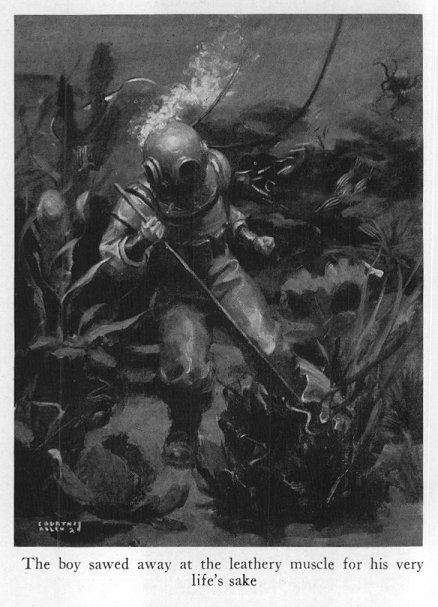

The boy sawed away at the leathery muscle for his very life’s sake … 316

-----

[blank page]

-----

[half-title page]

THE RED DIAMOND

-----

[blank page]

-----

p. 3

CHAPTER I

AMBOYNA

Wanted: Brave man; big danger; big money; no questions asked—nor answered. Write B. 73 “Sentinel” office.

A wiry little man with a gray beard, a shock of bushy gray hair, and steel-sharp gray eyes read this advertisement, one July afternoon in one of the advertising columns of the New York “Sentinel.” For over an hour he had been sitting in the lobby of New York’s largest hotel wearily watching the passing crowd.

“Sounds good to me,” he muttered to himself and sprang to his feet with the sudden swiftness of a young man, in spite of his gray hairs. Even as he spoke, a slim, black-eyed

-----

p. 4

boy stole up behind him and smote the old man mightily on the back.

“Judson Adams, you ’re under arrest!” he rumbled, in what he intended to be a deep bass voice, gripping the little man by the shoulders so that he could not turn around. “Will you come quietly, or shall I send for a patrol-wagon?”

Wriggling like an eel, Mr. Adams finally managed to catch a glimpse of the boy’s grinning face.

“Freddie Perkins!” he cried excitedly. “I ain’t seen you since we come back with the Blue Pearl!”

“Hello, Jud,” returned the boy, grasping the old man’s outstretched hand. “You ’re looking younger than ever—not a day over eighty.”

“There you go! Makin’ funny cracks at my age as usual,” returned Jud, peevishly. “How come you here, anyway?”

The grin faded from Fred’s face.

“I ’m looking for a job,” he said slowly.

“Sho! that ’s too bad,” said the old man, sympathetically. “Why, I thought you put

-----

p. 5

your share of the Blue Pearl into your uncle’s business an’ was a president or a foreman or somethin’ with him.”

“I did,” returned Fred. “Last week the business, the uncle, and all busted. I wish now I had gone to college with Bill Bright and Joe Couteau.”

The old man nodded his head wisely.

“Yes,” he said, “that ’s most certainly what you ought to have done. You young chaps seem to think that you ain’t goin’ to live much beyond twenty. Life ’s apt to last quite a piece longer. Eddication ’s the first thing; there ’s plenty of time to get all the money you need afterward,” he went on, as he convoyed the boy to an empty lounge. “Big Jim Donegan took my Blue Pearl and Inca Emerald money,” he resumed, as they sat down together in a quiet corner, “and invested it for me, an’ the interest is rollin’ in faster ’n I can spend it. It ’ll be a favor if you ’ll let me lend you enough to put you on your feet again.”

Fred shook his head emphatically. “You are certainly a good scout, Jud,” he said, pat-

-----

p. 6

ting the old man’s shoulder affectionately, “but I won’t borrow a cent from any one. I ’m going to take your advice, however,” he went on, “and get an education just as soon as I can get the money together. Tell me what you are doing in New York.”

The old man’s face fell.

“I ’m waitin’ here for Jim Donegan,” he replied. “He ’s upstairs attendin’ some kind of a meetin’ of gem-collectors. I been visiting Jim for ’bout a week an’ I ’m sure anxious to get back into the open again. These cities kind of smother me. Not but what Jim ’s taken mighty good care of me,” he added scrupulously. “The more I see of cities,” the old man continued earnestly, “the more I like deserts. I wish so much that it kind of hurts that I was off again with you an’ Bill Bright an’ Joe Couteau on the way to Goreloi or followin’ the Trail to Eldorado. What do you think of this?” he finished abruptly, passing the advertisement, which he had been reading, over to Fred.

The boy read the paragraph with the same interest which Jud had shown.

-----

p. 7

“Answer it,” he advised, “and send me word if there ’s any chance to let me in on it. Would n’t it be dandy,” he went on, “if we could have another trip like the one we went on after the Pearl with Bill Bright and Joe Couteau!”

“It sure would,” agreed Jud. “Bill would go in a minute an’ so would Professor Amandus Ditson, who went with Joe an’ Bill an’ me after the Emerald an’ give me a better idee of scientific chaps than I ever expected to get. Joe, though, is out of it. He ’s took all the money he made on both expeditions an’ has gone back to Akotan an’ is arrangin’ to get teachers an’ government protection for his tribe.”

“Good for old Joe!” returned Fred, heartily; “he ’s got the right stuff in him. Here ’s my address,” he went on, slipping a card into the old man’s hand. “I must run along. If there ’s anything doing in this big-danger, big-money scheme, let me know. I ain’t much on danger, but I sure need a piece of that big money.”

“I seem to remember a boy who did n’t

-----

p. 8

think of danger when I was fightin’ for my life with that devil-fish,” returned Jud, affectionately. “If it had n’t been for you, I would n’t be here now. An’ if there ’s anythin’ goin’ on, you ’ll be in it.” And with a final hand-grip, the two separated.

That night, Jud sent to the address given in the paragraph which had so captured his attention, a letter reading as follows:

Dear Mr. B. 73:

Your advertisement in the New York “Sentinel” to hand.

I ’m a fairly young man with considerable experience in big danger. I ’ve been a sailor and a pearl-diver in my time and have trapped and prospected clear up beyond the Circle. I was one of the party which brought back the Blue Pearl for Mr. James Donegan, the president of the International Lumber Company, and last year was on the expedition which got him the Inca Emerald from South America. I can give you his name for reference and that of Professor Amandus Ditson, of the Smithsonian Institute at Washington. If you and me, Mr. B. 73, decide to do business together, I can probably get two more

-----

p. 9

chaps to go along with us whom I can depend on.

Hoping to hear more from you about this big danger (likewise the big money),

Yours respectably,

Judson Adams

Late that afternoon, Mr. Donegan, the multi-millionaire head of the lumber trust, best known to his intimate friends as “Big Jim,” came up to Jud’s room where the old man was reading his paper after a ride through the park in Mr. Donegan’s imported car.

The lumber magnate seemed a little embarrassed.

“Would you mind, old man, if I left you

-----

p. 10

alone this evening?” he asked. “To-night is the dinner of the Ends-of-the-Earth Club. I tried to get you a ticket, but the guest-lists were closed.”

Jud grinned up at him cheerfully.

“Don’t you mind me, Jim,” he responded, “I ’ve got to meet a man this evening on business, anyhow, so you run right along an’ make a night of it.”

“All right,” returned the other, relieved. “I won’t go off without you again.”

Promptly at eight, Jud arrived at the Hotel Peerless and, upon inquiring at the desk, received one of the much-coveted invitations to the dinner of the Ends-of-the-Earth Club, which took its name from those lines of Kipling:

The Ocean at large was our share,

and which included in its membership explorers, big-game hunters, and wanderers from all over the world.

Jud was shot in an express elevator to the

-----

p. 11

banqueting-hall on the twentieth floor. There, amid a buzz of voices and the pleasant background of laughter, he found himself seated at one of the small tables next to a massive, red-faced man with bristling, graying red hair who was none other than Big Jim Donegan whom Jud had left only a short time before. The lumber king leaned forward in great astonishment.

“Jud Adams, you old sport! How in the world did you get here?” he boomed.

“You need n’t think you ’re the only man who can go to these swell dinners,” returned Jud, delightedly. “The thing that bothers me, though,” he went on, “is who invited me.”

At this point the other occupant of the little table took a part in the conversation.

“Perhaps I can explain,” he said in a low, rather precise voice. “Youa re here, Mr. Adams, as my guest.”

Jud stared at him, bewildered. The stranger was a tall, slim, rather distinguished-looking man with a pale oval face and a tiny, waxed mustache. It was his eyes, however,

-----

p. 12

which made him a man to be remembered anywhere. One was black as charcoal, while the ohter, in which he wore a monocle, was ice-blue. Jud had the feeling as he stared at the stranger that two men were looking out at him from the same face.

“Are you ‘B. 73’ who advertised about big danger,” he queried incredulously.

“Why not?” returned the other, quietly.

“Well,” answered Jud, bluntly, “you don’t look as if you knew much about it.”

The other stared at him fixedly for a moment without reply. Then a strange thing happened. The eye which held the monocle seemed to contract and the round glass shot across the stranger’s face into the other eye where it was caught and held while the unknown sat staring at Jud as if nothing had happened. Then, still without saying a word, he passed a handkerchief across his face and, with the gesture, his white, even teeth disappeared. His cheeks hollowed, his mouth puckered, and the face which stared into Jud’s became on the instant that of an old, old man. As the trapper shrunk away from him, the

-----

p. 13

other reached one hand to the side of his head. There was a sharp click and the next moment he was holding out one of his ears to the horrified Jud. The whole performance was so unnatural and unexpected that Jud sprang to his feet, whereupon the stranger spoke again.

“You don’t seem to be very brave yourself,” he remarked, restoring his teeth and ear as he spoke, and, with a blink, shooting his monocle back to the blue eye whence it came.

“I ain’t, hey!” Jud was beginning angrily when Big Jim Donegan interposed.

“Now, go easy, Jud,” he said, soothingly. “You ’re making the same kind of mistake that you made about Professor Ditson before you started with him for the Inca Emerald. This is Captain Vincton and I ’ve known him for a good many years. It was through him that I got the Rajah Ruby, one of the best stones in my collection. The captain ’s a great joker,” he went on, “and has charge of the native police in British North Borneo, which they tell me is no job for a timid man. I ’ve seen you change your face and do that

-----

p. 14

monocle stunt before, captain,” he went on, turning to the other man who had been listening impassively to the conversation, “but I never knew until to-night that you had an artificial ear.”

“I lost the real one the night I got your ruby,” returned the captain, in his curious, soft drawl. “Old Toku, the Dah of Dipa, got through my guard once with his barong and I was lucky that it was my ear and not my head that I lost.”

“I know what you can do in a pinch, captain,” returned the lumber king, “but I want you to become better acquainted with my old friend Jud Adams. In spite of his advanced age, Jud ’s chuck full of nerve and grit.”

“I ain’t a day older than you be, Jim Donegan,” snapped Jud, who was very sensitive about his age, “an’ I can do anythin’ you can or your friend here with the eyeglass—an’ a blame sight better.”

“Sure you can,” returned Mr. Donegan, soothingly. “You ’ve proved it many a time. Jud ’s the best shot in the Northwest,” he

-----

p. 15

went on, turning to Captain Vincton again.

“I know it,” returned the captain, bowing toward the bristling little trapper, who only glowered back at him. “When I got his letter, I turned down all other applicants and arranged this meeting immediately.”

“What does this mean, Jud Adams?” demanded Mr. Donegan, regarding the little trapper with affectionate sternness. “Have n’t I invested your money so that you get a steady income for life—more than you can spend? Why do you want to go off risking your life again when you might grow old comfortably and be up in Cornwall or down here with me in New York?”

“That ’s just it,” snarled the little man, while his gray hair and beard seemed fairly to bristle with energy. “I don’t want to grow old. I read where a chap named Stevenson wrote that the best way for a man to keep from growing old is to live dangerously. That ’s me! I want to live dangerously. I want to travel an’ explore an’ have good fights again an’ perhaps do somethin’ big for

-----

p. 16

somebody before I go down into the dust—” and the little man stopped, half-confused at his own enthusiasm.

Mr. Donegan started to protest again, but was interrupted by Captain Vincton.

“Wait a minute,” he said, incisively. “What I have in mind is exactly what Mr. Adams is seeking. Danger, money, help—that sounds like a good mixture, does n’t it?”

“You bet!” returned Jud, earnestly. “I ’m tired of cities an’ crowds an’ movies an’ theaters. I want to get out where I can breathe sky-air an’ sleep under the stars.”

“Good,” returned the captain. “If you go with me, it ’ll be months before you sleep under a roof again.”

“Now, Mr. Donegan,” he went on, as that gentleman started to speak, “let me see if I can convince you that Mr. Adams ought to go with me. In the first place, am I right in understanding that you have the largest and best collection of gems in the world?”

“Not the largest,” returned the lumber magnate; “the ex-King of Spain and one of

-----

p. 17

the Rothschilds have larger collections, but I claim that mine is one of the best.”

“What about diamonds?” Vincton asked.

“I ’m not so good in diamonds as some,” returned Mr. Donegan, “although I own what is probably the finest black diamond in this world as well as the Dragon, which belonged to an Emperor of China and is the largest yellow diamond known to collectors. I have others, but those are the best.”

“What ’s the rarest kind of diamond?” inquired the captain again.

“Well,” said the old lumber king, reflectively, “there ’s the Hope Diamond which is a brilliant blue, but the blues are not especially rare diamonds. Perhaps the Dresden Green, one of the crown jewels of Saxony, which weights forty carats and is a fine apple-green in color, is the rarest.”

“How about a red diamond?” inquired the captain.

Mr. Donegan shook his head.

“No red diamond large enough for a collecion has ever been found,” he said. “There

-----

p. 18

are some rosy diamonds, but there is no such thing as a large red diamond in any collection.”

“How about a red diamond,” went on Captain Vincton, “larger than a pigeon’s egg and bright as a big of petrified fire?”

Jim Donegan’s face flared as red as the diamond which Captain Vincton was describing. With no near relative left in the world, the old man’s gems had become dear to him as children and his agents were constantly ransacking the markets of the world for rare or beautiful specimens which, when found, he bought regardless of price.

“The Prince of Monaco was said to have a red diamond,” he said, finally. “When I was last in Europe I stopped to look at his collection. The red diamond was a red sapphire. The great red diamond which used to be among the crown jewels of Portugal was a spinel ruby. No,” he concluded, shaking his head again, “the whole world does n’t hold a diamond of the color and size you describe.”

“What price for a red diamond of the first

-----

p. 19

water, cut in a way, of which the secret has been lost for a thousand years, a diamond with a color like clear red flame on water—what would it be worth to you?” he insisted.

Big Jim Donegan drew a deep breath.

“Half a million dollars!” he snapped out at last.

There was a pause during which the many-keyed clamor of the dinner surged on around them unheeded. At last Captain Vincton spoke again.

“That sounds like a reasonable sum,” he said. “For five hundred thousand dollars even a timid chap like myself would be willing to take chances,” and he stopped as if he had finished.

“Go on,” urged Big Jim Donegan.

“Yes, go on,” piped Jud Adams. “What you got back of all this talk about diamonds big as ostrich eggs?”

“Pigeon was the word I used,” corrected the captain.

“Well, let ’s have it,” urged Jud. “I ’ve listened to some tall treasure-stories in my day an’ I ’m all set to hear this one.”

-----

p. 20

“Well,” resumed the captain, in his quiet voice, “last year I was cruising in the Sulu Sea after some Papuan pirates who were making trouble. One broiling day, we came across an unconscious white man drifting in a curious, crescent-shaped canoe.

“He was in a bad way from hunger and thirst and heat-stroke. I got him back to the island and sent a hundred miles down the coast for a missionary doctor—but it was too late. He became conscious before he died and told me that he had been to the Island of Amboyna.”

Again the captain came to a full stop, as if the name explained everything.

“Yes, yes,” said Jim Donegan, after waiting in vain for him to go on. “I heard you. Amboyna. A fine name for a Pullman car, but it don’t mean anything in my young life. What about the Red Diamond?”

“Every native in the Far East,” returned the captain, “knows the story of the mysterious Island of Amboyna hidden away somewhere among the reefs and shoals in the shallow sea between Australia and New Guinea.

-----

p. 21

For hundreds of years the story-tellers in the streets, old men around the camp-fires, and mothers to their children have told the story of Amboyna. A thousand years ago, a white tribe deserted their city on the Oxus, founded by Alexander the Great, in the face of a Tartar invasion from the North. They sailed down the river and across strange seas until they came to an unknown island with a great mountain in its interior, guarded by ferocious beasts and man-eating tribes. The fugitives fought their way to the mountain and there they have lived ever since. Some day, their priests have taught them, men shall come from the West bringing a golden pearl, the symbol of peace, who will help and not harm. For these men is kept the sacred Red Diamond. Afterward, the People of the Peak, as they call themselves, will come back to their city and become a great nation,” and again the captain stopped.

“Sounds like a story from the Arabian Nights,” commented Mr. Donegan, while old Jud sniffed skeptically.

“Yes,” agreed Captain Vincton, quietly,

-----

p. 22

“it does sound like a fairy story. I ’ve never believed in a treasure-city although I have an old sergeant in my troop who claims in his youth to have visited the Island of Amboyna and come back safely. This castaway, whom we rescued, said that not only had he visited the island but, by some bit of wonderful luck, got through the ring of tribes which surround the mountain and actually visited the City of the Peak itself. He gave me the latitude and longitude of the island, and a rough map showing where the only harbor on the island is located and the trail which leads through the morasses and jungles straight to the city itself. You see,” he went on after another pause, “the poor fellow was very grateful for the little I was able to do for him. He told me, too, that he had seen the Red Diamond itself in one of the temples and he did not believe there could be anything like it in all the world.”

The captain’s voice had sunk low before he finished and there was a rapt look in his strange eyes as if once more he listened to

-----

p. 23

the tale told by the dying man. The silence was broken again by Jim Donegan’s voice.

“Captain,” he said, “I ’m sure you believe what the man told you, but these treasure-cities of the East are mirages. The poor fellow might have been telling you a dream of his delirium. I would n’t take any stock in a story like that without some real proof.”

“I feel the same way,” chimed in Jud, from where he sat.

As they spoke, Captain Vincton glanced from one to the other with a half-smile on his clean-cut face. Then, without a word, he slipped his hand into an inner pocket and passed to the lumber king a tiny package about the size of a Lima bean. The outside of it was composd of some felt-like substance like fine wood-fibers matted together.

“Open it!” he said.

With some difficulty Mr. Donegan pulled apart the fibers with his great blunt fingers until there suddenly dropped into his guarding hand a small stone which gleamed and flashed like a drop of crimson flame. Hold-

-----

p. 24

ing this to the light he looked at it intently. Then he felt it all over and held it up to his cheek as if to test its temperature. Finally he spoke and it was evident that he was greatly excited.

“There ain’t any possible doubt about it,” he said. “That stone is a small red diamond. It has the gleam and flash of a diamond and it feels cool and greasy to the touch as all real diamonds do. Where did it come from?”

“McFee, the man who died, gave it to me,” explained Captain Vincton. “He had it from the priests of the Temple of the Red Diamond to show his people and hasten the coming of the Golden Pearl, which they believed would bring them peace and prosperity and restore them to their lost city. McFee said that the priests had a quantity of these small red diamonds and that there were others in the possession of the more prominent members of the tribe. Probably,” went on Captain Vincton, “before they left India they had discovered a drift of these red diamonds near their lost city.”

-----

p. 25

Mr. Donegan pondered the captain’s explanation for a long moment.

“What do you want me to do about all this?” he said at last.

“Nothing at all except bid on the Red Diamond when we get it,” returned the captain, calmly. “I came to New York to find out first, whether a red diamond, such as McFee described, was worth risking my life and money on; second, to pick up a good man to go along with me.”

“What about the Golden Pearl?” inquired Jud, who had been staring first at one speaker and then at the other.

“That ’s where you come in,” returned captain Vincton. “I know the one coast in the world where yellow pearls are found in considerable abundance, but I ’m no diver. It ’ll be up to you to find a good yellow pearl before we start. Then, with McFee’s map and chart and the help of old Sergeant Bariri of my company, I think we can get through the cannibals and reach the city, if any one can. What do you say?”

“Before you say anything,” broke in Big

-----

p. 26

Jim Donegan, explosively, “you listen to me. I ’ll grub-stake this trip, provide the diving-suit, the bearers, the boat, and everything else and agree to pay you a half million dollars for the Red Diamond if it ’s as per description. If not, you keep the diamond and I lose the money. How ’s that strike you?”

“That suits me,” returned Captain Vincton, promptly. “You and I have done business together before and I ’ll be glad to have you back of me again.”

Jud still hesitated.

“The captain here may be all right, though he don’t look it,” he said at last, “but I ’ll feel more comfortable if I can take along a couple of chaps of my own choosing.”

Captain Vincton was not at all offended at Jud’s frankness.

“It ’s my monocle and my timid nature which is holding Mr. adams back,” he remarked. “That ’s the reason I wanted to have a brave man like him along with me.”

“Jud,” said Mr. Donegan, earnestly, “you ’re making as much of a mistake about Captain Vincton as you did about Professor

-----

p. 27

Ditson when you went after the Inca Emerald. Who are the fellows you want to take with you anyway?”

“Those kids, Bill Bright an’ Fred Perkins,” returned Jud, promptly.

This time it was the captain who demurred slightly.

“This trip is no place for boys,” he said.

“I ’ll vouch for these two,” returned Mr. Donegan. “Will has been on two dangerous trips and Fred on one and they both of them made good. Moreover, I ’d like to nominate Professor Amandus Ditson to go along too. His knowledge of native life might be a great help.”

“All right, all right,” returned Captain Vincton, resignedly. “If you ’re going to finance this expedition, you certainly have a right to say who goes. Personally, I would n’t choose a professor and a couple of small boys as traveling companions among the man-eaters of Amboyna.”

“You ’ll find they shape up all right,” returned Jud heatedly, “even if they don’t wear window-panes in their eyes. I ’ve been in

-----

p. 28

some tight places with all of them and they certainly stood by me fine. I only ask one thing,” he went on, turning to Mr. Donegan; “you tell Professor Ditson to lay off snakes this trip. Let him collect butterflies or birds’ eggs, but no more snakes. I dream of that blame bushmaster even yet which he and Will collected when we were after the Emerald.”

-----

p. 29

THE FAR EAST

Some six weeks after the meeting at the dinner of the Ends-of-the-Earth Club, a little group of passengers stood at the bow of the steamer Malay and watched the northern coast of Borneo show across the South China Sea. Will Bright, whose adventures have already been chronicled in “Boy Scouts in the Wilderness,” “The Blue Pearl,” and “The Inca Emerald,” was the same young viking as ever, with blue eyes, a shock of copper-colored hair, and square-set shoulders, in vivid contrast to his old schoolmate Fred Perkins, lithe, dark, and swift as in the days when he won the mile run for Cornwall and voyaged to Goreloi after the Blue Pearl. Beside him was Professor Amandus Ditson, with his hooked beak of a nose and ice-blue eyes, coldly confident and self-contained as when

-----

p. 30

he led the expedition which brought back the great Emerald from the haunted lake of Eldorado. Near him was Jud Adams, the old trapper and Indian fighter, sharp-eyed, gray-bearded, and still sensitive about his age. With them, too, was a new figure, Captain Vincton, faultlessly dressed, with monocle and waxed mustache, apparently the last man to lead an expedition among the savage beasts and still more savage men of the South Seas.

Old Jud felt that way, in spite of the reputation for cool daring which Jim Donegan, the lumber-king had given him, while Professor Ditson, who had spent half of his life collecting in tropical jungles, did not attempt to conceal his contempt for his immaculate companion.

As they reached the shore of that vast, mysterious island, the largest of the East Indies, whose unexplored jungles and towering mountains conceal so many mysteries, the sea was the color of rose-leaves, and above a shore of misty blue the sunset sky showed pale gold and apple-green. Across the water came the breath of the tropics, compounded

-----

p. 31

of the pungent odor of cocoanut-oil, the earthy perfume of the palm-groves, and the smoke of innumerable woodfires.

As soon as they landed at the tiny port of Maceo, Captain Vincton conducted the whole party to the quarters which he occupied as chief of police of the province of North British Borneo.

His quarters consisted of a cool, comfortable house surrounded by a large courtyard which was used as a drilling-ground for his command of picked native police, whose barracks flanked the house. As the party entered the compound the whole company were drawn up to receive their captain. All of them showed their Malay blood in their height, which rarely exceeded five feet, their supple, wiry figures, and tiny hands and feet. In front of them all stood Sergeant Bariri, one of the captain’s most trusted men. Formerly a chief of a fierce interior tribe, he had been captured when he tried to raid a town protected by Captain Vincton’s men. Confronted by a long term of imprisonment, he had suggested to the captain that he would

-----

p. 32

like to work out his time serving in his troop. Knowing his reputation for desperate courage the captain had his sentence suspended, allowed him to enlist, and he had become his right-hand man. The sergeant was a gaunt, dark little man, well past middle age, with every ounce of superfluous flesh burnt off him by the hot sun of the tropics, and his arms and bare legs, which showed beneath his sarong,—a kind of kilt worn by all Malay tribes,—seemed made of black wire.

As the captain approached, the sergeant saluted, with a wide grin on his fleshless face. There was a rattle in the rank as the men grounded their carbines, and a swish as each trooper flashed into the air his barong, the heavy knife with which every Malay trooper is armed. Captain Vincton regarded his men for a moment silently with a grim smile on his thin lips. As he looked at them, once again his monocle shot across his face from his right eye, and a second later was seen to be firmly screwed into position in his left. Accustomed though they were to this accomplishment, yet a little murmur of admiration

-----

p. 33

went up involuntarily from the men, for, like the other natives, they still regarded this glittering glass which leaped from one eye to the other as indicating uncanny powers on the part of their leader. Then, for the first time, the captain addressed them. “O evil-doers,” he said in the purring, hissing Malay tongue, “I see that ye have grown fat in my absence from lack of work. Undoubtedly ye deserve punishment for your sloth and your many wickednesses!” Accustomed to this kind of talk from their leader, whom they adored almost as much as they feared, the dark little men in front of him grinned cavernously.

“Suppose, however,” went on the captain, “that in spite of your badness I had brought back presents from the far lands in which I have been, what would you desire most of all?”

“Mostizos—scissors!” shouted the whole troop, with one accord.

Captain Vincton regarded them fiercely. “Aha, scoundrels!” he said, “I can read your thoughts even when afar off.” And opening

-----

p. 34

a large package which his orderly brought to him, he presented each man in the troop with a pair of the much-desired scissors. These were received with the hissing intake of breath which among the Malays takes the place of cheers.

By the time the review of the company was over, dinner was announced, and Captain Vincton led his guests to where a table was spread in a screened upper veranda. From a long way off deep in the jungle came the steady throb of tom-toms, where some of the natives would dance all night long. Across a darkening violet sky, in which strange stars were beginning to flare, flitted processions of great fruit-bats on their way to the heavy-laden fruit-trees which fringed the village, remnants of abandoned plantations which the inexorable jungle had claimed. Near the table a group of native servants dressed in snowy white waved long fans, while behind each guest stood another, to assist in serving the dinner.

Old Jud, who had been appalled to learn what Big Jim Donegan paid a week for serv-

-----

p. 35

ants in New York, was much impressed. “Cap’n,” he remarked, “all these butlers and fanners must set you back quite a ways.”

“Yes,” agreed the captain, “it ’s a bit of an expense. The best of them cost me all of six cents a day in American money. The rest work for their board.”

The dinner itself, to the dismay of Jud, the epicure of the party, seemed to consist of but one dish, the celebrated rice-taffle of the East Indies. Before each guest was placed an enormous platter of rice, cooked with that hot, delicious dryness of which only Chinese cooks seem to know the secret. On this, as a foundation, was heaped a layer of grilled boneless chicken, cooked in spices and garnished with a chutney sauce. On the top of this was spread schools of tiny fish, salted, broiled, and roasted, and highly seasoned with another sauce. Then came spiced meats, candied bacon, toasted cocoanut, boiled shrimps, salted almonds, bamboo sprouts, and sliced water-chestnuts, while every crevice and cranny of the edifice was chinked with delicious mushrooms. Even the boys had to stop before they

-----

p. 36

had finished the first layer. Jud alone, made his way down to the rice-foundation, soaked and saturated with the juices and spices of all that had gone before. After a few spoonsful of this, however, he stopped with a long sigh.

Captain Vincton regarded him with admiration. “You have come nearer to finishing a taffle than any white man I ever met,” he remarked courteously.

Before Jud could answer, enormous dishes of different kinds of fruit were brought in, many of which Jud and the boys had never seen before. Among these were fully a dozen different kinds of bananas, selected from the fifty or more varieties found in Borneo. Red, yellow, and green in color, they ranged from giants eighteen inches long down to tiny, pear-shaped specimens which made but a single melting mouthful. Then there were lansats, which looked like white plums and tasted like ripe oranges, sweet lemons, shaddocks, mangostans, and custard-apples full of seeds surrounded by a delicious fragrant pulp which was taken out by long, narrow spoons provided for the purpose. At the sight of this

-----

p. 37

dessert Jud’s appetite revived, and even Will and Fred, who had declared they would never eat again, managed to sample several varieties of the number which were set before them.

“Wait,” said the captain, when they complimented him on his dessert. “The durian, the best of all fruits is coming. Some people can’t stand its smell, so I have saved it until the last so as not to spoil your dinner.”

“Bring ’em in,” returned Jud, stoutly; “there ain’t nothin’ can spoil my dinner. I ’ve got just about room left for a durian, whatever it is.”

At a word from Captain Vincton, one of the servants brought in a great tray containing dark green fruits, each one the size of a cocoanut. As the waiter approached, Will and Fred involuntarily buried their noses in their napkins. Through the room spread a devastating odor, like a mixture of sewer-gas and garlic.

Just then Jud turned his head and came within range of this gas barrage. “Help, help!” he gasped, burying his face in his napkin like the boys.

-----

p. 38

“It has rather a high bouquet,” admitting the captain; “but if you once taste a durian, you’ll forget all about its smell.”

“No man with a nose could ever forget that smell,” murmured Jed, plunging still deeper into his napkin.

Captain Vincton picked up a knife and, where five lines showed faintly, cut through the rind of the strange fruit. As the fruit opened out under his strong hand, the smell of decaying onions became so strong that the boys fled to the window. Only Professor Ditson, who was quite accustomed to the ways of tropical fruit, held his ground, along with the native waiters, who regarded the boys in mild astonishment. The crescent-shaped slices were satiny white within and filled with a mass of cream-colored pulp in which were imbedded several seeds about the size of chestnuts. The captain filled a spoon from one of the segments and passed it over to Jud.

“Swallow that,” he said, “and be happy!”

The tears streamed from Jud’s eyes as a wave of the pungent, penetrating odor swept over him. “I only hope I can keep it down!”

-----

p. 39

he murmured. “This is worse than that flying dragon I ate in South America.” Then, holding his breath he thrust the spoon apprehensively into his mouth. As the flavor of the fruit reached his palate he stretched out his hand for another crescent. “Best eatin’ I ever had,” he remarked between mouthfuls.

Thus encouraged, Will and Fred at last tried a spoonful. One taste convinced them. The flavor of the durian was that of a rich, creamy custard flavored with almonds, with a curious, spicy taste besides. It was neither acid nor sweet nor juicy, but more of a food than a fruit.

“One durian is worth the whole voyage!” remarked Jud, when at last he had finished; and the boys agreed with him.

That night they all slept out on the cool, screened veranda high above the ground. The minute the sun went down, the sudden darkness of the tropics fell upon the tiny village nad the vast jungle beyond. Little waves of coolness swept through the hot, moist, scented air, and in a sky like dark-blue velvet flamed and flared the great constella-

-----

p. 40

tions of the South. Directly overhead shone the Southern Cross, which used to serve as a sky-clock for the old Spanish voyagers four hundred years ago and by which the natives still tell the time of the night. Suddenly a red glow showed on the horizon, and through the heat-haze above the edge of the jungle wheeled the full moon, red as blood. Streamers of mist floated up from the steaming jungle and stretched across its face like the bars of a furnace.

As if only waiting for the rising of the moon, the whole jungle burst into a pandemonium of noises. Insects buzzed and whirred from the trees, and from every pool, frogs croaked, and rattled and bellowed. Above them all, however, sounded an appalling medley of howls and screams. Starting low with a wail of unutterable sadness, the chorus rose higher and higher into a volley of full-throated shrieks of terrible agony, which finally died away in a long, quivering sob. Old Jud stood it for awhile. Then he tumbled out of his hammock. “Somethin’s got to be done about this,” he remarked to Will, who

-----

p. 41

was vainly trying to bury both ears in his pillow at once. “It must be a massacre.”

On the way to the far end of the veranda, where Captain Vincton was sleeping, he passed Professor Ditson’s hammock. “What ’s the matter,” inquired the latter, as he heard Jud’s bare feet go padding past him.

“I ’m goin’ to wake up the captain,” returned Jud, briefly, “an’ see if something can’t be done to help those poor natives who are being killed out there in the jungle.”

The professor chuckled. “I would n’t do that,” he suggested; “the captain needs his sleep. Those are n’t natives; those are a species of small monkey,” he explained. “They always howl like that when there is a full moon, and they are enjoying themselves.”

For some time Jud could not be convinced. “Well, all I can say,” he finally remarked, as he returned to his hammock, “if them monkeys scream that way when they ’re happy, I ’d sure hate to hear ’em when they feel bad.”

Early the next morning, before the sun was hot, Sergeant Bariri took Fred to his cocoanut grove for a drink of “tuba,” as the fresh

-----

p. 42

sap of the cocoanut-palm is called. The sergeant’s house was a tiny one, almost surrounded by the towering trunks of the cocoanut-palms, which ran up for a hundred feet before they branched. In the side of each, notches had been cut clear to the top. As they came to the first one, the sergeant slipped off his jacket and sandals, and barefooted, wearing a pair of short, baggy trousers, proceeded to walk up the tree as easily as if he were going upstairs, his long toes gripping the trunk at each notch just as surely as did his fingers. Swung across one shoulder he carried a hollow joint of bamboo, the open end of which was corked, while in his belt he wore a sharp, curved knife. Fred watched in astonishment as he mounted the palm to a dizzy height, his body hanging away from the smooth trunk at a dangerous angle. At the tip-top of the tree the branches of a blossom stalk of the palm had been tied together and their cut ends thrust into another larger bamboo-joint, which was nearly full of the fresh sap. Clinging precariously, supported only by the grip of his knees and toes at over a

-----

p. 43

hundred feet above the ground, Bariri nonchalantly filled his bamboo from the sap-container, cut and dropped to the ground from the near-by branches a half-dozen green cocoanuts, and then proceeded to walk backward down the tree as easily as he had climbed it.

“I ’m glad to see you back again safe and sound!” exclaimed Fred, as the sergeant slipped lightly to the ground from the last notch.

Bariri grinned widely. “That nothing,” he assured the boy, “I teach you to climb higher tree than that.”

“Much obliged,” returned Fred, doubtfully.

Uncorking his wooden bottle, the sergeant handed it to the boy. Fred found the tuba clear and cold as ice, sweet and spicy, with just enough tartness to make it appetizing—as invigorating a drink as could be imagined on which to begin a hot day. Then with a cut of his keen knife Bariri bisected one of the green cocoanuts. It was half full of sweet, nutty cream, perhaps the most delicious tast-

-----

p. 44

ing substance in the whole vegetable kingdom.

On the way back to breakfast they stopped at Bariri’s hut, small, but neat and clean. In place of glass, the windows had, as panes, squares of translucent shell. There Fred met the sergeant’s wife, a tiny woman, not more than four feet high, with snapping black eyes, who ruled her husband with a rod of iron. As they left the hut they met the sergeant’s little ten-year-old girl wearing a wreath of crimson hibiscus flowers around her blue-black hair and playing with her tame fawn. The year before she had found two tiny fawns where their mother had hidden them in the brush. One was spotted like most fawns, but the other was pure white. Taking one under each arm, she had started back home with them. The way was long, however, and the day ht, and finally she had to let the spotted fawn go to return to hits hiding-place, where the anxious doe was waiting for it. The white one she carried back, and brought it up on a bottle. It was so tame that, although it wandered into

-----

p. 45

the near-by jungle to feed, it always came back at her call.

As they started back by another route, their way led along the edge of the sluggish, muddy river. The path which they followed was a full fifty yards from the water, and, as they walked, Fred started to follow the edge of the bank, hoping to catch sight of some of the strange fish which haunt Eastern rivers. Before he had taken many steps he felt the sergeant’s hand on his arm and was respectfully, but firmly, dragged back to the path.

“No walk close to river,” remarked Bariri, in his broken English. “This river not healthy.”

Even as he spoke, a half-grown pig, one of many which wandered about the village, left a group of his friends in the shade of a thicket and trotted down to the water.

“Look!” whispered Bariri, suddenly gripping Fred’s arm. What seemed to be a floating log, with two knots in one end, showed in the murky water. Just as Fred realized that the log was moving against the current, there was a sudden swish, and a

-----

p. 46

vast ridged tail swung out of the water and through the air like a huge scythe catching the unfortunate pig full in the side with tremendous force. there was a terrified squeal and the pig shot through the air in a wide arc and struck the water with a splash. As he came to the surface, just behind him showed the long pointed head and evil yellow eyes of a great crocodile. The next instant a pair of vast jaws filled with rows of knife-like teeth flashed open. There was another piteous squeal and the jaws of death closed, leaving only a swirl showing in the water. Bariri turned to Fred, who had been watching the tragedy with horrified interest.

“There ’s where you ’ll be,” he remarked, “if you not mind old man Bariri.”

Fred drew a deep breath. “I ’ll say I will!” he promised.

The rest of the party were just sitting down to breakfast by the time Fred reached the house. Captain Vincton had planned to spend a week at the village so that his guests might rest after the voyage and have a chance to become used to the climate and country.

-----

p. 47

Will and Professor Ditson had decided to spend the time collecting birds and butterflies, while Fred wanted to go fishing in some stream not infested with crocodiles.

All of these plans were set aside that morning by the arrival of a Dyak runner. Just as the party had seated themselves in the shade after breakfast, along one of the narrow forest trails in the jungle, which lapped almost to the edge of the compound, sounded the rapid pad-pad of bare feet. The next moment the fringe of boughs screening the edge of the jungle was dashed apart and a Dyak boy, about the age of Will, burst into the open. The red-brown skin of his bare legs and breast gleamed like tinted ivory, and, unlike the Malays who made up the captain’s body-guard, his eyes were brown and almond-shaped, while his blue-black hair was cut in a neat bang across his forehead and held back by a twisted circlet of pale yellow silk. In one hand he carried a naked serpent-kris, a vicious-looking weapon with a wavy, double-edged blade, and a long crimson gash showed across his bare left shoulder.

-----

p. 48

As the boy reached the steps he staggered and his face went suddenly gray as if overlaid with ashes.

“O Heaven-Born!” he gasped, bowing before the captain although so weak from fatigue and loss of blood that he could scarcely stand, “the Masai had burned our village and slain and wounded many of our men and have carried off my father and many others to be slaves. I alone have escaped and traveled through the jungle many days to bring the word to thee.” His voice trailed off into silence and he clung half-fainting to a post of the veranda.

Captain Vincton sprang to his feet. His monocle dropped unheeded from his eye, his face flushed a dark red, and when he spoke, there was not a trace of drawl in his incisive voice.

“Fret not thyself,” he said to the wounded boy in the native language. “The Masai knew that I was away or this would not have happened. I will go even myself to their village, release thy people, and bring their chief back to justice, and they shall pay

-----

p. 49

heavily for the harm they have done. Rest here quietly and be healed of thy wounds.” And he spoke a few quick words to Sergeant Bariri.

A moment later and he was again the immaculate exquisite with whom the rest of the party had voyaged. “I shall have to be away awhile,” he apologized; “but my people will make you comfortable. I shall only take Bariri and some bearers and will not be gone long.”

“Do you mean that only two of you are going to tackle a whole tribe?” exclaimed Jud, incredulously.

“Yes,” returned the captain, quietly.

“How about your leave of absence,” inquired Professor Ditson.

“Leaves of absence don’t count when there is any trouble in this distric,” returned the captain, emphatically.

“I don’t know how the rest of you feel,” said Will, who had been looking at the captain as if he had never seen him before, “but I ’m going with Captain Vincton if he ’ll take me.”

-----

p. 50

“Same here,” said Fred, briefly.

“I ’m in this too,” was Jud’s contribution to the conversation.

“Perhaps there may be a chance to get some new specimens,” remarked Professor Ditson, precisely. “I also would like to come if the captain will permit me.”

Captain Vincton looked at them all for a moment before replying, and his face flushed with pleasure as he sensed their changed attitude toward him.

“I shall be glad to have your company,” he said at last, slowly.

The next morning everything was ready. For a moment they stood in the clear blaze of the tropical sun, where a turquoise sky yearned down to a lapis sea and the air seemed mingled fire and crystal. Three steps along a path which showed like a sword-slash through the damp green of the jungle, and they wer in another world, where the light was dim and green-shadowed and filtered down through interlacing boughs of trees draped and festooned with strange vines and creepers.

-----

p. 51

Once again they were afield, and the clear sweet thrill of adventure ran like fire through their blood. Bariri had arranged every detail of the trip with the utmost care and forethought—save one. The first day out, the native cook whom he had brought along proved to be a total loss. Some of the messes he cooked had a taste which even Professor Ditson, used to lean living on collecting-trips, could not abide. As for that epicure Jud, he grew more and more mournful every hour.

The crisis came when at one meal the Indian brought in a large platter of what looked like shrimps cooked in oil. Jud ate several before he discovered that they were fried dragon-flies with the wings removed. For dessert that day the inspired chef laid before them a box of fat white grubs which he had dug out of the trunks of sago-palms. These grubs feed entirely on the pure starch of the palm-pith, which are turned by their digestive juices into sugar, and are regarded by the natives of the jungle much as candy is among white races. This last course was too much for Jud.

-----

p. 52

“Here ’s where that well-known traveler, Judson Adams, Esquire, lives on fruit for the rest of this trip,” he announced positively.

Captain Vincton regarded his guests in despair. If the white men cooked for themselves, they would lose caste with the bearers and trail-cutters whom Bariri had brought along; and above all things, in dealing with natives it is important to keep their respect. On the other hand, a few more days of native cooking bade fair to break down the morale of the whole party.

“I ’d give anything for a good cook,” the captain soliloquized as their chief retired, much puzzled that the white men did not care for the delicacies he had prepared. Just as he voiced this cry of civilization the bushes parted, and into the clearing stepped the strange figure of a dwarfish old man. He wore only a pair of short trousers, with a startling array of weapons at his belt. His hair was long and—a most unusual thing for a native—he wore a drooping mustache. On his back was a large basket in which he carried his provisions and various belongings,

-----

p. 53

while hard at his heels trotted a scrawny yellow dog. In broken Spanish the stranger introduced himself.

“I am Mateo, of the Mindari tribe, O Chief,” he began. “I have heard of thy fame and would travel with thee.”

“What can you do?” inquired the captain.

“I know all the trails and can track and hunt better than any man in the jungle,” returned the old man, modestly. “Moreover,” he went on, “I am such a cook as no white man has ever known.”

“He certainly commends himself very highly,” broke in Jud, who understood Spanish, “but if he can cook anything besides insects, I say we give him a trial.”

In addition to the array of knives which he wore in his belt, Mateo carried in one hand the sumpitan, the inevitable companion of every Mindari hunter. This was none other than the blow-pipe, which Jud and Will and Professor Ditson had seen used in South America. It was a hollow iron-wood tube, fully six feet in length, with a tiny, gleaming squirrel-tooth thrust in the farther end for a

-----

p. 54

sight. Like a rifle equipped with a bayonet, the sumpitan ended in a long, keen spear-head. Armed with one of these, native hunters can kill game anywhere within a range of fifty yards, while the spear-head makes it effective also for use at close quarters.

The old tracker seemed well and favorably known to all the native members of the party. “He best shot in all his tribe,” confided Sergeant Bariri to the captain.

“Let ’s see him shoot,” demanded Jud jealously, who had heard the sergeant’s last remark.

Bariri jabbered something to the old hunter in his own dialect and the latter grinned understandingly. Taking a wild orange, he fastened it at about the height of a man’s shoulder on the branch of a thorny bush. Then moving back some forty yards, he reached with his left hand into the lizard-skin pouch which he wore fastened to his belt. From this he drew a handful of the tiny darts made from slivers of sharpened bamboo, smeared with a mixture of the sap of the poison-tree and cobra-venom and feath-

-----

p. 55

ered with a tuft of silk-cotton. Jud watched him critically.

“If he can hit that orange once out of ten shots with them pizen darts, I ’ll say he ’s some shot,” he remarked.

Drawing a breath which made his bony chest stand out like a box, the old man inserted a dart, gripped the blow-gun at one end with his two hands close together, sighted for a second, and, with a sudden puff, sent the tufted missile whirring through the air like a bee. There was a tiny thud followed almost instantaneously by another puff. Almost as quickly as a man could shoot an automatic revolver, the Mindari sent six darts in succession at the mark. As he lowered his weapon Jud rushed over to examine the orange, and found that no less than five of the vicious little thorns of death were buried deep in the target.

Once again the old hunter repeated the feat, this time with hardened pellets of clay which he used for killing small birds. Then he showed Jud, whom he seemed to recognize as a fellow-sportsman, a special compartment

-----

p. 56

in his belt where he kept a number of larger and heavier darts, weighted with tin. These contained double the amount of venom used in the others. With a dart like these, he assured Jud, he had killed a rhinoceros.

While this conversation about blow-guns had been going on, Captain Vincton had been questioning Bariri further about the Mindari and suddenly turned to the wizened-up little hunter.

“It has come to my ears, O Mateo,” he said solemnly, “that the Mindari and man-eaters. How know I that if I take you along, you will not eat us all up?”

“We be a fierce people,” answered the old man, grinning cavernously, “but it is the fault of our ancestors. It was a wolf who first brought a Mindari warrior into this world. ‘How am I to live?’ he asked the wolf. That is the reason why in times past that the Mindari ate men—because they could get nothing else. Nowadays, however,” he went on reassuringly, “we eat only the bravest and

-----

p. 57

strongest of our enemies so that we too may grow more brave and strong.”

“It is really a compliment to be eaten by a Mindari,” murmured the captain to Jud, who had been listening with bulging eyes.

“I don’t calculate to let any Injun eat me whether he does it as a compliment or as a pleasure,” returned the old trapper, positively. “What I want to know,” he went on, “is whether he can cook a good meal.”

“Of a certainty I can,” returned Mateo, who understood the last part of Jud’s remark, “any time, anywhere.”

“Go to it,” retorted Jud; “let ’s see you cook one right here and now.”

Without a word, the Mindari laid down his sumpitan and his basket and tied his dog to a sapling. With a blow of his machete he cut off from a near-by clump a dry joint of a dead bamboo about three quarters of an inch in diameter. Splitting this in half, he cut with the sharp edge of his blade a groove clear through the convex side of one of the pieces. From the other half of the joint he

-----

p. 58

fashioned a sharp-edged strip which looked much like a paper-knife. Placing the first joint on a low rock, flat-side down, he placed the edge of the wooden knife across the groove and began to saw back and forth with it against the convex side of the joint. In a few seconds a little heap of wood-dust began to trickle into the groove. Faster and faster he sawed, until a tiny conical pile of dust appeared at the bottom of the slit. In about ten seconds a faint smoke showed, which increased to a cloud as the saw moved faster and faster. Suddenly stopping, Mateo struck the edge of the joint a blow to dislodge any sparks which might be clinging to its under-surface, and then snatched it up, leaving a little cone of charred dust, at the apex of which a bright spark showed. Upon this he hurriedly placed a pinch of tinder made from palm-husk, which he drew from his pouch, and carefully blew against the spark until it burst into a blaze. Over this he heaped splinters of dry bamboo, and in less than a minute had a good fire crackling and snapping in front of him. With another

-----

p. 59

blow of his machete, he cut a green joint of bamboo some six inches across and a foot high, open at one end and closed by the joint at the other. Filling this with clear water from the spring, beside which the party was camping, he placed it over the fire propped up with a forked stick on either side. The green bamboo joint did not burn, but allowed the heat to penetrate its surface, and in a few moments the water was bubbling in this wooden kettle. While waiting for the water to boil, Mateo cut from the same bamboo clump a cluster of fragrant green shoots. These he dropped into the water as it came to a boil. Then, still using his machete, he deftly made a rude knife and fork and a platter from split bamboo joints. On this last he dished out a few moments later the savory steaming contents of his green kettle, and with a flourish passed the knife, fork, and dish of boiled shoots to Jud. The whole operation had taken him less than fifteen minutes.

Jud sat down on a near-by stump and sampled the steaming contents of his platter.

-----

p. 60

With the very first taste, an expression of intense satisfaction spread over his face. The young bamboo sprouts had a taste something between asparagus and young cabbage, and made as delicious and wholesome a dish as could be found anywhere in the East.

“Cannibal or not, I move he be elected cook of this expedition,” mumbled Jud, between mouthfuls; and after the rest of the party had sampled the savory sprouts, Jud’s motion was unanimously carried.

-----

p. 61

THE CLOUDED TIGER

From that day on, Mateo became one of the most important officials of the expedition. No one ever knew when he got up or when he went to bed, or when or where he found the provisions which he served to them.

One morning, breakfast began with mangoes, like small melons, and ripe paw-paws, which Mateo had found time to gather, fresh and dewy, in the dawn-dusk. After this course, he raked out of the hot coals half a dozen charred and blackened objects, each about the size of a large cantaloupe. Laying these on platters of smooth green palm-leaves on the top of a stump, the old man split them open with his machete. Each half seemed filled with a smooth, creamy batter.

“Breadfruit,” explained Captain Vincton,

-----

p. 62

much delighted. “They are the first I ’ve seen for years.”

Falling upon them, spoon in hand, each one of the party soon sampled the new food. Jud said it was like mashed potatoes and milk; Captain Vincton stood out for Yorkshire pudding; while the boys thought it tasted more like hot sweet rusks than anything else. The breakfast ended with broiled palm-pigeons, beautiful green birds, which Mateo had brought down from the tops of trees with his deadly little clay bullets.

Later that morning, Mateo introduced them to another delicacy, of which Jud approved even more highly. They had been following a winding trail through tree-ferns which had trunks like palms and leaves thirty feet long, like beautiful ferns in their color and tracery. All around them gleamed patches of brilliant orchids, shining like stars in the scented, steaming air, which Will said reminded him of a hothouse. Suddenly Mateo, who had been leading the way, stopped. Just in front of him towered a pandanus-tree, whose great glossy, curved leaves

-----

p. 63

curled down like green plumes. The lowest tier sagged heavily from their stems, and seemed to be thatched with gray shingles, the nests of the native bees. From these, at intervals, clear drops fell, making a long line od drippings on the ground beneath the tree.

Without a word, the old Mandari stooped and smeared his bare arms, legs, face, and head with honey. Then, with his machete, he cut a length of tough green liana. With this he fastened himself to the tree, in a wide loop. Then, leaning back on the knot of the loop, with his basket on his back, clinging to the sides of the tree with his tough feet, he walked up the smooth trunk, pushing the loop ahead of him with every step. In less than a minute, he was directly under the gray honeycombs, out of which suddenly swarmed a perfect cloud of bees.

“He ’s a goner,” exclaimed Jud, who had been watching him. “They ’ll sting him to death.”

As coolly as if he were safe on the ground, the old Indian broke off comb after comb of the gray wax, filled to overflowing with

-----

p. 64

delicious honey. Not until his basket was nearly full did he stop and begin to descend, followed by the cloud of buzzing, whirling bees, not one of which molested him or even alighted on his smeared body.

“I guess Borneo bees don’t have stings,” observed Jud, as he watched him come down, still unscathed.

A moment later, when a little scouting-party of the descending column alighted on the back of Jud’s neck, he changed his mind.

“Ouch! Help! Fire!” he bellowed, as the fierce stings pierced his skin, and, waving his hands wildly, he plunged into the underbrush for shelter, followed hastily by the rest of the party, who kept a safe distance from Mateo until the bees had gone back to their tree-top.

The honey was delicious, sweet, limpid, and fragrant as the best white-clover honey made by United States bees, and Jud took an extra helping to make up for his stings, and afterward argued that Mateo was one of those rare and fortunate people whom for some unknown reason insects will not bite

-----

p. 65

or sting. Professor Ditson took no stock in that theory, but was most positive that without the honey with which he was smeared, he would be stung like any one else. An accident which happened later that day showed that the scientist was right.

It was just before the noonday siesta, when the whole party slept through the hottest hours of the day in their hammocks in the shade, that Mateo, for some unknown reason, started to cut down a small tappan-tree with his machete. The very first stroke dislodged a long dead branch near the top, which fell directly on his head. The sudden blow knocked the old man over, and before he could get up, a swarm of hornets, big as bumblebees, with stings like red-hot fish-hooks, settled upon him, while at the same time, to add to his troubles, a multitude of red-and-green ants rushed out from a hole in the branch and bit him like fire. Mateo explained to Jud, afterward, that they were so many that they had to take turns in biting him—but probably that was an exaggeration. At any rate, he was so stung and

-----

p. 66

bitten that it was many hours before he stopped calling them all the bad names he knew in Indian, Spanish, and English.

It was Jud at last who calmed him by admiring the armory of weapons which he wore in his belt, all made by native smiths from gray, hand-forged steel and of wonderful temper and keenness. On his left side the old man wore a campilan-a straight double-edged sword, whose blade was wide at the tip and narrowed toward the hilt. The dull gray steel, with its myriads of interlacing lines, showed how anxiously and tirelessly some unknown smith had hammered and forged and tempered the weapon. With such a sword, balanced and weighted for dreadful blows, Mateo told Jud he had killed the rhinoceros, the most dreaded of all Bornean beasts, the keen blade shearing through even the two-inch armor which that battleship of the jungle wears.

On the right-hand side of the belt of the old hunter was thrust a serpent kris, a short left-handed weapon with a narrow, wavy, double-edged blade, used only for thrusting.

-----

p. 67

The one worn by Mateo had an ivory handle and was beautifully inlaid with gold. Besides these tow deadly weapons, the old man wore, next to his campilan, a baron, perhaps the most effective cutting weapon for its size ever invented. This one had a wide blade shaped like a cleaver, with a heavy back and a thin, razor-like edge, while the handle was wound with palm-fiber, to give a firm grip.

“What do you do with all these slashers and stickers, Mateo?” inquired Jud.

The old Indian smiled grimly. “In the jungle one has to fight for his life often,” he replied at last. “When those times come, a good blade is a man’s best friend.”

After the siesta was over, they started off again in the cool of the afternoon through a part of the jungle more beautiful than any which they had yet passed through. Among the trees drifted butterflies, beautiful as the flowers whose colors they imitated. Here and there the trees were lined and laced with the flaming scarlet blossoms of the D’Albertia creeper, whose flowers have a color

-----

p. 68

which no paints yet discovered by man can imitate.

“How large do the flowers grow?” inquired Will, of Professor Ditson, as they admired the jeweled vine.

“Some which I found on the island of Mindanaeo,” returned the scientist, “had blossoms three feet across.”

As he spoke, Fred stooped and held up a vivid green pitcher-plant, whose gold-lined pitcher held nearly two quarts of water and, unlike the American variety, was provided with a neat cover. Another one of the same family had a narrow pitcher some twenty inches long, growing on a plant many feet in length. Just beyond these pitchers, Jud came across a number of small trees heavily laden with tempting fruit. Some were crimson in color, others of a deep gold, blotched with pink, while a third variety was all amber and russet, all of them being divided into two lobes separated by a deep groove, unlike any fruit which the old trapper had ever seen before. They had just passed through a fruit-

-----

p. 69

belt, the remains of orchards planted by some native tribe whose clearings had long been swallowed up by the jungle. There Jud had sampled several varieites and found them all good. Concluding that these brilliant specimens were equally good to eat, he picked a handful of the ripest. Just as he started to bite into one of them, Professor Ditson happened to turn around and saw what he was doing. For once he showed considerable excitement.

“Drop it!” he shouted. “They belong to the apocynaceæ family.”

“This belongs to the Judson Adams family,” returned the old trapper, obstinately, “and they smell mighty good.”

“Exactly,” returned the professor; “they look good and they smell good and likewise they taste good, but the Indians call them ‘apples of Satan.’ ”

“How come?” inquired Jud, somewhat taken aback by the name.

“Because,” Professor Ditson assured him, “if you eat a piece of any of them as big as

-----

p. 70

a half-dollar, in about half an hour you ’ll be tied up in knots. That condition lasts for some time, depending on the individual.”

“Yes, an’ then what?” queried Jud, as the scientist turned away to examine an orchid perched like a golden butterfly on a tree-fern.

“Then you die,” the professor called back as he joined the rest of the party.

“Huh!” grudged Jud, tossing away the treacherous fruit, “apples always did make trouble for the Adamses ever since Eve’s day.”

A little later on, he had a far more disastrous experience with another one of the demons of the plant-world. Turning off into a little by-path to get a look at a jungle-cock which had just strutted past, he brushed against the branches of a tree covered with glossy dark-green leaves, which looked much like those of the laurel at home. Instantly a dreadful burning pain shot through him, so agonizing that involuntarily he cried out. at the sound, Bariri, who was near, hurried to him and was immediately joined by Captain Vincton and the rest of the party. They found the old man writhing on the ground in

-----

p. 71

a paroxysm of pain which not even his tried and tested fortitude could conceal.

“It ’s the devil-tree,” said the captain, “one touch of its leaves is an unspeakable agony.”

“Is n’t there anything we can do for him?” implored Will, the perspiration standing on his forehead as he watched the suffering of his old friend.

“Nothing,” returned the captain; “he has been touched lightly and the pain will stop soon.”

The time seemed long enough to poor Jud. Gradually, however, the waves of agony, which had thrilled through every nerve of his body, died away, and, weak and shaken, he smiled wanly up at the sympathizing group surrounding him.

“What with Satan-apples and devil-trees,” he said at last, getting to his feet with difficulty, “this jungle ’s no safe place for respectable people.”

Although he protested that he was ready to go on, the old man was so plainly weakened by the dreadful venom of the tree that Captain Vincton decided to make camp im-

-----

p. 72

mediately and rest there the next day, until Jud was entirely recovered.

The next morning, as always, the party was up before sunrise in order to take advantage of the cool hours before the blinding heat came, in which every exertion was a burden.

After breakfast, Professor Ditson decided to spend every minute of this unexpected holiday in collecting.

“Collect anything but snakes,” requested Jud, weakly, from his hammock.

Professor Ditson was somewhat annoyed by his unreasonable attitude. “Do you realize, Mr. Adams,” he remarked reprovingly “that in these latitudes are found some of the largest, rarest, and deadliest of all the serpents? Surely you would be glad to be known as a member of a party which succeeded in securing a full-grown specimen of the hamadryas or king-cobra, the deadliest and fiercest serpent known, or to help secure a thirty-foot reticulated python.”

“I would not,” returned Jud, positively; “I want to be known as one of a party which

-----

p. 73

keeps as far away as possible from snakes, big, little, pizen, or harmless.”

Professor Ditson shook his head sadly at such a lack of scientific interest, but in view of Jud’s invalid condition, agreed to confine himself that day to butterflies and to have nothing to do with reptiles. In Borneo, however, it is sometimes easier to make than to keep such a resolution.

Across a low open glade where the party had made camp and which ran for several hundred yards into the jungle, butterflies of indescribable beauty drifted like floating flowers. Upon these the scientist descended armed with his butterfly-net and collection-jar. Among the first which he caught was the Arjuna butterfly, whose wings seemed powdered with grains of golden-green and blotched with moon-shaped spots of the same. He also secured five specimens of the specter butterfly, whose white wings reflected a variety of prismatic colors, the pale-winged peacock butterfly, the sapphire-colored little blue, and a host of others. As Will stood with him watching this kalei-

-----

p. 74

doscope of shifting beauties, Professor Ditson suddenly drew a deep breath and gripped his arm convulsively. Just in front of them, hovering over a patch of marshy ground, floated the most beautiful creature which the boy had ever imagined. It was a butterfly whose velvet-black and green wings had a spread of over seven inches, larger than many a bird. The wings were long and pointed, like those of the spynx-moth, with a curved band of brilliant emerald-green spots extending across them from tip to tip. Every spot was shaped like a small, triangular feather, which increased the insects resemblance to a brilliant bird. The butterfly’s body was of gold, and it had a crimson breast.

“It ’s the Poseidon, one of the most beautiful of all the bird-wing butterflies,” whispered the professor. “Don’t move,” he hissed, gliding like a snake toward the wet moss on which it settled as he spoke. Inch by inch, with the utmost care, he moved toward the spot where the great butterfly gleamed from the ground, waving its pointed wings like jeweled fans as it sucked up

-----

p. 75

moisture from the tiny puddle at whose edge it had alighted. At last the professor reached a point not more than six feet away from the living jewel which gleamed just before him. Slowly and with infinite pains, he stretched out the long handle of his butterfly-net, ready to swoop down upon the unwary butterfly as soon as he was near enough to do so with every chance of success. Perhaps at the last moment, in his excitement, he thrust the net out too quickly; perhaps the butterfly had drunk its fill and decided to go elsewhere; at any rate, whatever the reason, just as his outstretched arm quivered before it made the final swoop, the unfeeling Poseidon suddenly wheeled, swift as a swallow, into the air, and flew away. Although Professor Ditson swept his net through the air like lightning, he missed the jeweled wings by an inch, and, with a deep groan, stood watching the escaping bird-wing sail over the tops of the low trees like a meteor and disappear in the distance.

The great scientist walked dejectedly back to Will. “For years,” he said sadly, “I have

-----

p. 76

been trying to obtain a Poseidon for my collection. Once I had one, but the ants ate it before I reached home. Another time I was captured by a raiding-party of Moros just as I caught a superb specimen. My friends,” continued the professor, in a melancholy voice, “were kind enough to ransom me, but the Moros kept everything I had, including that magnificent bird-wing. The last I saw of my Poseidon it was pinned to the hat of a Moro chief.”

“Perhaps you ’ll get another one later in the day,” sympathized Will.

“I ’m afraid not,” returned the professor, pessimistically. “One does n’t often have a chance to catch two bird-wings in one day.”

He had no more than spoken when Will suddenly pointed excitedly to a flowering shrub showing through the thickets about fifty yards away. It was covered with brilliant yellow blossoms, and over these, like a gleaming bird, was poised the figure of another of the great butterflies. This one had broader wings than the Poseidon, and its

-----

p. 77

colors, a flaming gold and pansy-purple against the same background of velvety black, gave the new-comer an indescribably vivid beauty. The professor stared at the new butterfly like a man transformed. In all their life-and-death adventures together, Will had never seen him so excited. His long, gaunt arms shook as if he had a chill; beads of perspiration stood out all over his craggy face; and when he spoke it was in a strained, harsh, and unnatural voice.

“A Nova!” he said reverently; “a new specimen never before collected or catalogued!” And with the words he rushed toward the butterfly, his net streaming out behind him like the tail of a comet.

By the time that he had reached the bush, the butterfly had floated like a bird of fire over to another patch of flowering shrubs. Unheeding his steps, his eyes fixed only on that golden will-o’-the-wisp, Professor Ditson zigzagged back and forth through thicket, clearing, and jungle alike. Rattans, which the Indians called jungle-ropes, slender as strings and circled with cruel thorns, tangled

-----

p. 78

about his legs and slashed through clothes and skin alike. Now and then their grappling-lines wound about his waist and held him fast or hurled him headlong to the ground. When that happened he would struggle to his feet again, slash his way clear with the machete which he wore at his belt, and, with clothing torn and hanging in shreds, and his face, hands, and body bleeding from a score of gashes, still pursue the bird-wing, which danced on ahead like the image of gold with which fleeing Fortune used to lure her votaries, according to the old Greek mythology.

At first, Fred laughed heartily as he watched the excitement of Professor Ditson, usually so self-controlled and unruffled. Even Will, who had more of the collecting instinct, could not keep from smiling at the scientist’s frantic efforts. Only Captain Vincton and the Indians did not laugh. They knew from cruel experience the truth of the native proverb, “He who runs in the jungle, races with Death.” As the course of the flitting butterfly brought it nearer to

-----

p. 79