What to Do and How to Do It; or, Morals and Manners Taught By Examples, by Samuel Griswold Goodrich. (New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1844)

front cover and spine: Peter Parley—dressed in his trademark “small clothes”—talks to children; his gouty foot rests on a footstool

-----

[title page, Hemingway copy]

[title page, 1856 copy]

AND

HOW TO DO IT;

OR,

MORALS AND MANNERS

TAUGHT BY

EXAMPLES.

BY

PETER PARLEY.

NEW YORK:

WILEY & PUTNAM.

1844.

-----

[copyright]

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1843,

By S. G. GOODRICH,

in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the United States,

for the District of Massachusetts.

-----

[p. iii]

CONTENTS.

PAGE

Chap. I. Everything is made to be Happy … 1

Chap. II. Do as you would be done unto … 6

Chap. III. Truth … 8

Chap. IV. The Choice, or Good and Evil … 16

Chap. V. What Kind of Heart have you got? … 22

Chap. VI. What Kind of Heart have you got? … 31

Chap. VII. Charity … 34

Chap. VIII. Charity … 41

Chap. IX. Charity … 48

Chap. X. Charity … 51

Chap. XI. Selfishness … 57

Chap. XII. The Value of Character … 59

Chap. XIII. Justice … 61

Chap. XIV. Humility … 63

Chap. XV. Mildness … 65

Chap. XVI. Candour … 67

Chap. XVII. Prejudice … 70

-----

p. iv

PAGE

Chap. XVIII. Mercy … 84

Chap. XIX. Courage … 87

Chap. XX. Patience and Impatience … 89

Chap. XXI. Cheerfulness and Gloom … 92

Chap. XXII. Good Habits and Good Manners taught by Example … 95

Chap. XXIII. Obedience … 108

Chap. XXIV. How to settle a Dispute …114

Chap. XXV. Politeness … 120

Chap. XXVI. Boasting … 133

Chap. XXVII. Weakness of Character … 136

Chap. XXVIII. Self-reliance—Perseverance … 142

Chap. XXIX. Gratitude … 150

Chap. XXX. Amusement … 153

Chap. XXXI. Do not be too positive … 156

Chap. XXXII. Attention … 160

Chap. XXXIII. Vanity … 165

Chap. XXXIV. Do not be discouraged by Difficulties … 169

-----

[p. 1]

WHAT TO DO,

AND HOW TO DO IT.

CHAPTER I.

EVERYTHING IS MADE TO BE HAPPY

If any one of my young friends will get up early in the morning and go forth among the birds, the insects, the four-footed beasts, he will see that they all seem made to be happy.

-----

p. 2

The robin in singing its song, the sparrow in building its nest, the swallow in pursuing its insect prey, the doves in their fond intercourse with each other, the busy crow in feeding its young—all seem made to enjoy their existence, and all seem to accomplish the design for which they were created.

The busy bee in storing away its honey, the bustling ants in carrying on the various affairs of the hill, the grasshopper in playing his little fiddle, the butterfly in his search of the sweetest flower, even the beetle in rolling his ball, the cricket in chirping beneath a heap of stones, and the spider in making or mending his net—all appear to be in pursuit of happiness, and all seem to obtain it.

And the squirrel, skipping from tree to tree, the mouse in gnawing a hole to get at the meal, the frog in the brook, the toad in his burrow of earth, the wild deer in the forest, the sheep upon the grassy hill side, the cows in the meadow, the dog at his master’s side—these all declare that they are in pursuit of enjoyment, and that they find what they seek.

-----

p. 3

Happiness, then, is the end and object for which these creatures were made: and they all, taken in a general view, attain it. Life to them is a blessing. It was given them by a good and loving Creator, who meant that they should enjoy it.

And were not human beings made for happiness too? Yes—and for even greater happiness than these birds, and insects, and quadrupeds. We are made not only to enjoy the pleasures of animal life, but those of the heart and of the mind: we are not only made to eat and drink, and perceive heat and cold, but to feel the beauty of virtue, and the grace of goodness; to enter the fields of knowledge, and enjoy the boundless pleasures of thought.

The Creator, then, intended us for happiness, but in giving us nobler endowments than those of mere animals, he has bestowed upon us liberty, or the power to act as we please. Here, then, he made a great difference between us and the beasts: he laid them under the laws of instinct: he placed in each of them certain wonderful aptitudes, habits, and powers, which govern and control them. Thus, obeying these laws, they

-----

p. 4

fulfil the designs of God, and attain the end of their existence. Man has good and evil placed before him, and he may choose which he pleases: it is God’s will that man should choose the good, and thus be happy: but still, having made us free, he leaves us to choose evil and suffer sorrow, if we will.

While God, therefore, guides the birds and fishes and insects and four-footed beasts, by their instincts, to happiness, He has left us to our own choice. It is for us to decide whether we will be happy or not. God has given us reason in the place of instinct, and if we will obey that reason wisely, and follow the paths which it points out, happiness is ours, not only for this world, but for that which is to come.

Now we do not send animals to school, and give them books, for God is their teacher: their instincts are all they need. But human beings are to be educated, instructed, and by a gradual progress, elevated to that high destiny for which they are qualified. Instruction is the means by which we are to be taught our duty, and by which we may accomplish the end for which we were created.

-----

p. 5

But instruction will not make us happy, unless we listen to it, and obey its teachings. We must not only know what is good and right, but we must pursue and do what is good and right.

We all desire to be happy: no one can by any possibility desire to be miserable. And how can we be happy? The answer is easy, to do good, and to do it in the right way. We must not only take care to have our hearts right, but our manners must be right: we must not only be honest, true, charitable, virtuous, but we must be amiable, kind, cheerful, agreeable. We must not make it our sole object to be happy ourselves, but we must constantly try to make others happy also. And how can we make others happy, if our manners, our looks, our words, our mode of speaking, are disagreeable?

Now proceeding upon the certainty that all my young friends desire to be happy, I write this book, to assist them in becoming so. I intend it to be a pleasant book, full of truth, but full of amusement also. My purpose is to teach young people the great art of life—that of doing right in the right way: that of being not only good, but agreeable.

-----

p. 6

CHAPTER II.

DO AS YOU WOULD BE DONE UNTO.

This sentence contains the substance of the moral law, that law which points out our duty to our fellow-men. Now what do we wish of our fellow-men—how do we desire that others should treat us? We wish them to treat us kindly, justly, charitably: we wish them to be polite, affectionate, cheerful, pleasant.

Let us then be kind, just, charitable, polite, affectionate, cheerful, pleasant to others. If all would observe this beautiful rule, which Christ himself has given us, how happy

-----

p. 7

should we be, and how happy should we make all around us! What a delightful world this would become, if every one would look about and do to his neighbour, as he would wish his neighbour to do to him!

To show how pleasantly this rule would work, let me tell you a story,—a true one:

The horse of a pious man happening to stray into the road, his heighbour put him into the pound. Meeting the owner soon after, he told him what he had done; “and if I catch him in the road again,” said he, “I will do it again.”

“Neighbour,” replied the other, “not long since I looked out of my window in the night, and saw your cattle in my headow, and I drove them out and shut them into your yard, and I will do it again.” Struck with the reply, the man liberated the horse from the pound, and paid the charges himself.

And let me tell my little readers, if they wish their playmates and companions to be kind to them, they can best secure their object by being kind themselves. Kindness begets kindness; doing good to others is the best way of doing good to ourselves.

-----

[p. 8]

CHAPTER III.

TRUTH.

Truth is conformity to fact, in a statement or representation. If I say that London is the largest city in the world, my statement conforms to fact, and is therefore true. If I say that Boston has more inhabitants than New York, my statement does not conform to fact, and therefore is not true.

There is one thing more to be considered, which is, that the statement must conform to fact in the sense in which it is meant to be understood. If I say a thing which is lite-

-----

p. 9

rally true, but which is not true in the sense in which I mean it to be understood, then I am guilty of falsehood, because I intend to deceive. The following story will illustrate this:

Two boys, who had been studying geography, were walking together one evening, when one of them exclaimed, “How brightly the sun shines!” The other boy immediately replied that, as it was evening, the sun did not shine. The first boy insisted that it did shine; whereupon a dispute arose, one of the boys insisting that the sun did shine, the other that it did not. At last, they agreed to leave the point to their father, and accordingly they went to him and stated the case. They both agreed that it was nine o’clock at night; that the stars were glittering in the sky; that the sun had been down for nearly two hours; and yet John, the elder of the boys, maintained that, at that moment, the sun was shining as brightly as at noon-day.

When the father demanded an explanation, John said that the geography he had just been studying, stated that when it was

-----

p. 10

night here, it was day in china—“and now,” said he, “of course the sun is shining there, though it is night here. I said that the sun shines, and so it does.”

To this the father replied as follows:

“What you say now, John, is true, but still, what you said to James was a falsehood. You knew that he understood you to say that the sun shone here—you meant that he should so understand you; you meant to convey a statement to his mind that did not conform to fact, and which was therefore untrue. You had a reservation in your own mind, which you withheld from James. You did not say to him that yoou restricted your statement to China—that was no part of your assertion.

“Truth requires us not only to watch over our words, but the ideas we communicate. If we intentionally communicate ideas which are false, then we are guilty of falsehood. Now you said to James that which was untrue, according to the sense in which you knew he would, and in which you intended he should, receive it, and therefore you meant to violate the truth. I must accord-

-----

p. 11

ingly decide against you, and in favour of James; you were wrong, and James is right. The sun did not shine as you said it did, and as James understood you to say it did.”

There are many other cases which illustrate this “truth to the letter and lie to the sense.” Some years since, when the laws against travelling on the Sabbath were in force, a man was riding on horseback near Worcester, in Massachusetts. It was on a Sunday morning, and the traveller was soon

-----

p. 12

stopped by a tythingman,* who demanded his reason for riding on the Lord’s day, and thus violating the law.

“My father lies dead in Sutton,” said the other, “and I hope you will not detain me.”

“Certainly not,” said the tythingman, “under these circumstances;” and accordingly he allowed the man to proceed. About two days after, the traveller was returning, and happened to meet the tythingman in the road. The two persons recognized each other, and the following conversation ensued:

“You passed here on Sunday morning, I think, sir,” said the tythingman.

“Yes, sir,” said the traveller.

“And you told me you were going to your father’s funeral—pray when did he die?”

“I did not say I was going to my father’s funeral—I said he lay dead in Sutton, and so he did; but he has been dead for fifteen years.”

*The word tythingman, in New England, is the title of a town officer, who sees to the observance of certain laws relating to the due observance of the Sabbath.

-----

p. 13

Thus you perceive that while the words of the traveller were literally true, they conveyed an intentional falsehood to the tythingman, and therefore the traveller was guilty of deception. I know that people sometimes think these tricks very witty, but they are very wicked. Truth would be of no value if it might be used for the purposes of deception; it is because truth forbids all deception, and requires open dealing, that it is so much prized.

It is always a poor bargain to give away truth for the sake of a momentary advantage or for the purpose of playing off an ingenious trick. To barter truth for fun or mischief is giving away gold for dross. Every time a person tells a lie, or practises a deception, he inflicts an injury upon his mind, perhaps not visible to the eye of man, but as plain to the eye of God as a scar upon the flesh. By repeated falsehoods, a person may scar over his whole soul, so as to make it offensive in the sight of that Being whose love and favour we should seek, for his friendship is the greatest of all blessings.

Truth is the great thing to be sought, and

-----

p. 14

falsehood the chief thing to be avoided. Truth is the foundation of most other virtues—of honesty, justice, and fidelity. No character is so much prized as that of a lover of truth, none so much despised as the liar and the deceiver, for falsehood lies at the bottom of almost every vice.

The Horse and his Groom.

A groom, whose business it was to take care of a certain horse, let the animal go loose into the field. After a while, he wanted to catch him, but the brute chose to run about at liberty, rather than be shut up in the stable; so he prance about the field and kept out of the groom’s way.

The groom now went to the granary, and got the measure with which he was wont to bring the horse his oats. When the horse saw the measure, he thought to be sure that the groom had some oats for him; and so he went up to him, and was instantly caught and taken to the stable.

Another day, the horse was in the field, and refused to be caught. So the groom

-----

p. 15

again got the measure, and held it out, inviting the horse, as before, to come up to him. But the animal shook his head, saying, “Nay, master groom; you told me a lie the other day, and I am not so silly as to be cheated a second time by you.”

“But,” said the groom, “I did not tell you a lie; I only held out the measure, and you fancied that it was full of oats. I did not tell you there were oats in it.”

“Your excuse is worse than the cheat itself,” said the horse. “You held out the measure, and thereby did as much as to say, “I have got some oats for you.’ ”

Actions speak as well as words. Every deceiver, whether by words or deeds, is a liar; and nobody, that has been once deceived by him, will fail to shun and despise him ever after.

-----

p. 16

CHAPTER IV.

THE CHOICE, OR GOOD AND EVIL.

There are few persons who do precisely as they ought to do. It is very seldom that any one, even for a single day, discharges every duty that rests upon him, at the same time avoiding everything that is wrong. There is usually something neglected, delayed, or postponed, that ought to be done to-day. There is usually some thought entertained, some feeling indulged, some deed committed, that is sinful. If any person doubts this, let him make the experiment; let him closely watch every thought and action for a single day, and he will perceive that what we say is true—that all fall far short of perfect obedience to the rule of right.

And yet, if a person can once make up his mind to do right, it is the surest way to

-----

p. 17

obtain happiness. I shall endeavour to illustrate this by an allegory:

The Garden of Peace.

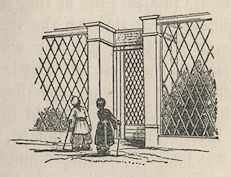

In an ancient city of the East, two youths were passing a beautiful garden. It was inclosed by a lofty trellis, which prevented their entering; but, through the openings,

they could perceive that it was a most enchanting spot. It was embellished by every object of nature and art that could give beauty to the landscape. There were groves of lofty trees, with winding avenues between them: there were green lawns, the grass of which seemed like velvet: there were groups of shrubs, many of them in bloom, and scattering delicious fragrance upon the atmosphere.

-----

p. 18

Between these pleasing objects there were fountains sending their silvery showers into the air; and a stream of water, clear as crystal, wound with gentle murmurs through the place. The charms of this lovely scene were greatly heightened by the delicious music of birds, the hum of bees, and the echoes of many youthful and happy voices.

The two young men gazed upon the scene with intense interest; but as they could only see a portion of it through the trellis, they looked out for some gate by which they might enter the garden. At a little distance, they perceived a gateway, and they went to the spot, supposing they should find an entrance here. there was, indeed, a gate; but, it was locked, and they found it impossible to gain admittance.

While they were considering what course they should adopt, they perceived an inscription over the gate, which ran as follows:

“Ne’er till to-morrow’s light delay

What may as well be done to-day;

Ne’er do the thing you ’d wish undone,

View’d by to-morrow’s rising sun.

Observe these Rules a single year,

And you may freely enter here.

-----

p. 19

The two youths were much struck by these lines; and, before they parted, both agreed to make the experiment by trying to live according to the inscription.

I need not tell the details of their progress in the trial: both found the task much more difficult than they at first imagined. To their surprise, they found that an observance of the rule they had adopted required an almost total change of their modes of life; and this taught them, what they had not felt before, that a very large part of their lives—a very large share of their thoughts, feelings and actions—were wrong, though they were considered virtuous young men by the society in which they lived.

After a few weeks, the younger of the two, finding that the scheme put too many restraints upon his tastes, abandoned the trail. The other persevered, and, at the end of the year, presented himself at the gateway of the garden.

To his great joy, he was instantly admitted; and if the place pleased him when seen dimly through the trellis, it appeared far more lovely, now that he could actually tread

-----

p. 20

its pathways, breathe its balmy air, and mingle intimately with the scenes around. One thing delighted, yet surprised him—which was this: it now seemed easy for him to do right; nay, to do right, instead of requiring self-denial and a sacrifice of his tastes and wishes, seemed to him a matter of course, and the pleasantest thing he could do.

While he was thinking of this, a person came near, and the two fell into conversation. After a little while, the youth told his companion what he was thinking of, and asked him to account for his feelings. “This place,” said the other, “is the Grden of Peace. It is the abode of those who have chosen God’s will as the rule of their lives. It is a happy home provided for those who have conquered selfishness; those who have learned to conquer their passions and do their duty. This lovely garden is but a picture of the heart that is firmly established in the ways of virtue. Its ways are ways of pleasantness, and all its paths are peace.”

While they were thus conversing, and as they were passing near the gateway, the youth saw on the other side the friend who

-----

p. 21

had resolved to follow the inscription, but who had given up the trial. Upon this, the companion of the youth said, “Behold the young man who could not conquer himself! How miserable is he in comparison with yourself! What is it makes the difference? you are in the Garden of Peace; he is excluded from it. This tall gateway is a barrier that he cannot pass; this is the barrier, interposed by human vices and human passions, which separates mankind from that peace, of which we are all capable. Whoever can conquer himself, and has resolved firmly that he will do it, has found the kay of that gate, and he may freely enter here. If he cannot do that, he must continue to be an outcast form the Garden of Peace.”

-----

p. 22

CHAPTER V.

WHAT KIND OF HEART HAVE YOU GOT?

Many people seem to think only of their external appearance, of their personal beauty, or their dress. If they have a handsome face, a good figure, and a fine attire, they appear satisfied; nay, more, we often see persons showing vanity and pride merely because they have beautiful garments on, or because they are called pretty or handsome.

Now I am not such a sour old fellow as to despise these things, it is certainly desirable to appear well, indeed it is our bounden duty to make ourselves agreeable; but I have remarked that those persons who are vain of outside show, forget that the real character of a person is within the breast, and that it is of vastly greater importance to have a good heart than a handsome person.

The heart within the body is of flesh, but

-----

p. 23

it is the seat of life: upon its beatings our life depends. Let the heart stop, and death immediately follows. Beside this, the heart is influenced by our feelings. If one is suddenly frightened, it beats more rapidly. Any strong emotion, or passion, or sensation, quickens the action of the heart.

It is for these reasons, because the heart is the seat of life, and because it seems to be the centre or source of our passions and feelings, that we often call the soul itself, the heart. Thus the heart of flesh is a sort of emblem or image of the soul. When I ask, therefore, what sort of heart have you got? I mean to ask what sort of soul have you got?

We often hear it said that such a person has a hard heart, and such a one has a kind or tender heart. In these cases we do not speak of the heart of flesh, but of the mind and intention. A hard heart, in this sense, is a soul that is severe, harsh, and cruel; a kind and tender heart, is a soul that is regardful of the feelings of others, and desirous of promoting the peace and happiness of others.

You will see, therefore, that it is very im-

-----

p. 24

portant for every individual to assure himself that he has a good heart. the reasons why it is important, I will endeavour to place before you.

In the first place, “God looketh on the heart.” He does not regard our dress, or our complexion, or our features. These do not form our character; they have nothing to do with making us good or bad. If God looks into the breast and finds a good heart there, a tender, kind soul, full of love toward Him and all mankind,—a heart that is constantly exercised by feelings of piety and benevolence,—he approves of it, and he loves it.

God does not care what sort of garment covers such a heart, or what complexion or features a person with such a heart has got. He looketh on the heart, and finding that good, he bestows his blessing, which is worth more than all the wealth of this wide world.

Personal appearance is of no value in the sight of God. It is only because men value it, that it is to be regarded. But upon the character of the hear, the favour or displea-

-----

p. 25

sure of God depends. It is of the greatest importance, therefore, for each person to see what kind of heart he has got. If he loves to do mischief; if he loves to say or do harsh and unkind things; if he loves to wound the feelings of others; if he loves to see another suffer; if he wishes, in any way, to injure another in his mind, body, or estate, then he has a bad heart; and God looks on that bad heart as we look upon a malignant and wicked countenance.

Before God, every heart has a character. We cannot see into the bosom, but God can. All things are transparent to Him, and he looketh on the heart as we do upon one another’s faces: and to Him, every heart is as distinctly marked as men’s countenances are to us. A wolf has a severe, harsh, and cruel expression in his countenance. A bad heart has as distinct an expression in the sight of God, as the wolf’s face to human eyes.

The second reason for having a good heart is, that it not only wins the favour of God, but of men. However we may fancy that mankind think only of outside appear-

-----

p. 26

ance, they do in fact think more of internal goodness. Mankind, in all ages and countries, love, respect, and revere the person who has a good heart; the person whose soul is habitually exercised by piety toward God and love toward mankind, is always esteemed and loved in return.

Such a person is almost sure to be happy; even if he is destitute of money, he has that which in this world is of more value, the good will, the sympathy, the kind wishes and kind offices of his fellow-men. If a person wishes success in life, therefore, there is no turnpike road to it like a good heart. A man who seeks to extort, to require, to command the good will of the world, will miss his object. A proud person, who would force men to admire him, is resisted; he is looked upon as a kind of robber, who demands what is not his own, and he is usually as much hated as the person who meets you on a by-road at night, and, holding a pistol in your face, demands your purse.

The proud person, the person who demands your respect, and tries to force you into good will toward him, turns your feel-

-----

p. 27

ings against him; [while?] the gentle, the humble, and the kind-hearted, appeal to the breast with a power we cannot resist. The person, therefore, of real power, is the person with a good heart. He wields a sceptre which men would not resist if they could, and could not if they would.

The third reason for having a good heart is, that while the exercise of a bad heart is painful, the exercise of a good heart is blissful. A heart that indulges in envy, malice, anger, revenge, jealousy, covetousness, becomes unhappy and miserable; a heart that exercises piety, love, charity, candour, peace, kindness, gentleness, becomes happy.

The exercise of piety and good feelings brings pleasure and enjoyment to the soul, as cool, fresh water does to a thirsty lip: bad feelings bring pain and misery to the soul, as bitter and poisoned water does to the palate and the stomach. A person, therefore, who indulges in bad feelings, is as unwise as one who refuses pure water and drinks poison.

The fourth reason for having a good heart is, that it is the surest way to be handsome.

-----

p. 28

A person with a good heart is almost always good-looking; and for this reason, that the soul shines through the countenance. If the heart is angry, the face is a tell-tale, and shows it. If the heart is exercised with piety, the countenance declares it.

Thus the habits of the soul become written on the countenance; what we call the expression of the face is only the story which the face tells about the feelings of the heart. If the heart is habitually exercised by malice, then a malicious expression becomes habitually stamped upon the face. The expression of the countenance is a record which sets forth to the world the habitual feelings, the character of the heart.

I know very well that some persons learn to put a false expression upon their faces: Shakspeare speaks of one who “can smile and smile and be a villain still.” This false veil, designed to hide a bad heart, is, however, generally too thin to answer its purpose. Mankind usually detect the veil of ypocrisy, and as flies see and shun a spider’s web, so mankind generally remark and avoid the hypocrite’s veil. They know

-----

p. 29

that the spider, the dastardly betrayer, is behind it, ready to make dupes and victims of those whom he can deceive.

The only true way, therefore, to have a good face, a truly and permanently handsome face, is to ahve a good heart, and thus have a good expression. There can be no genuine and abiding beauty without it: complexion and features are of little consequence. Those whom the world call handsome, have frequently neither regularity of features nor fairness of complexion. It is that indescribable thing called expression, the pleasant story which the countenance tells of the good heart within, that wins favour.

There are many other good reasons for having a good heart; but I have not room to tell them here. I must say a word, however, as to the means of curing a bad heart and getting a good one.

The first thing is, to find out what a good heart is, and what a bad heart is; and in making this inquiry it will much help you to read carefully the account given of Jesus Christ in the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. There are no pages like

-----

p. 30

these so full of instruction, and that so readily impart their meaning to the soul of the reader.

They give us a portrait of our Saviour,—and what a portrait! How humble, yet how majestic! how mild, yet how dignified! how simple, yet how beautiful! He is represented as full of love toward God, and toward manking; as going about doing good; as having a tender and kind feeling for every human being; as healing the sick, giving sight to the blind, and pouring the music of sound upon the deaf ear. Love to God, which teaches us to love all mankind, evidently filled the heart of Jesus Christ; and his great desire seems to have been, that all mankind should have hearts filled with the same feeling that governed his. A good heart, then, is one like Christ’s; a bad heart is one that is unlike Christ’s. A good heart is one that is habitually exercised by love to God and charity to man; a bad heart is one that is exercised by selfishness, covetousness, anger, revenge, greediness, envy, suspicion, or malice.

-----

p. 31

CHAPTER VI.

WHAT KIND OF HEART HAVE YOU GOT?.

Having learned what is meant by a good and bad heart, the next thing is to look into our own breasts and see what kind of a heart we ourselves have got. This is of first-rate importance, and therefore it is that I ask the question—“What sort of heart have you got, reader?”

Having, by careful examination, found out what sort of a heart you have got, then you are prepared to act with good effect. If you find that you have a good heart, a heart like Christ’s, filled with the love of God and feelings of obedience to God, and with love an charity to all mankind, evinced by a desire to promote the peace and happiness of all; then be thankful for this best of gifts, and pray Heaven that it may continue to be yours. An immortal spirit, with the prin-

-----

p. 32

ciple of goodness in it, is yours—and how great a blessing is that!

But if you discover that you have a bad heart, pray set about curing it as soon as possible. An immortal spirit with a principle of badness in it, is surely a thing to be dreaded; and yet this is your condition, if you have a bad heart. In such a case, repentance is the first step for you to take. Sorrow, sincere sorrow, is the condition upon which past errors are forgiven by God; and this condition must be complied with.

There is no forgiveness without repentance, because there is no amendment without it. Repentance implies aversion to si; and it is because the penitent hates sin, that the record of his offences is blotted out. While he loves sin, all his crimes, all his transgressions must stand written down andd remembered against him, because he says that he likes them,—he vindicates, he approves of them. Oh take good care, kind and gentle reader—take good care to blot out the long account of your errors, before God, speedily! Do not, by still loving sin, say to God that you are willing to have those

-----

p. 33

that you have committed, and those you may commit, brought up in judgment against you. Draw black lines around the record of your transgressions, by repentance.

And having thus begun right, continue to go on right. At first, the task may be difficult. To break-in a bad heart to habits of goodness, is like breaking a wild colt to the saddle or harness; it resists, it rears up, it kicks, it spurns the bit, it seeks to run free and loose, as nature and impulse dictate and as it has been wont to do before: but master it once, and teach it to go in the path, and it will soon be its habit, its pleasure, its easy and chosen way to continue in the path.

To aid you in this process of making a good heart out of a bad one, study the Bible, and especially that which records the life and paints the portrait of Christ. Imitate, humbly, but reverently and devoutly, his example; drink at the fountain at which he drank, the overflowing river of love to God.

This is the way to keep the spark of goodness in the heart; and to cherish this, to keep it bright, exercise yourself in good deeds, in good thoughts, in good feelings.

-----

[p. 34]

CHAPTER VII.

CHARITY.

Charity is that kindness of heart which makes us desirous of rendering others happy. It is one of the greatest of virtues, and without it, no one can be good. It is a pure love of mankind, and of all things that live, and breathe, and feel. It is a beautiful sentiment, and in the sight of God is of more value than all the gold and silver of the world. It is indeed the pearl of great price:

-----

p. 35

one who has it is rich in the sight of God; one who has it not, is poor indeed, though he may have lands and money in abundance.

The most common form of charity is that of giving alms to the poor: and every one who loves his money so well that he cannot part with a portion of what is not necessary for his own comfort, or that of his family, to aid the needy and the helpless, in the sight of God and true wisdom, is worse than a beggar. Rich in the things of this world, he is pinched with selfishness, which implies a miserable dearth of true riches.

Another form of charity is that of putting kind and favorable constructions upon the conduct of others. A person who is harsh in judging and severe in speaking of others is destitute of charity. I am afraid that some of my young friends, who are apt to say unpleasant things of their companions, are in this condition.

Think a moment of it, my gentle reader;—why should you desire to wound the heart of another—to tear his character to pieces? Have you any better right to injure the

-----

p. 36

feelings or reputation of another, than to wound his person? Is it not as bad to destroy his good name, as to break his bones? In the sight of God, one is as bad as the other; they both show a want of that love which we call charity, and this every good heart possesses.

There are many persons who think that it is witty to be severe; that it shows talent to find fault; that it displays superiority to be dexterous in picking out and showing-up the follies and foibles of others. This is a great mistake, for of all kinds of vulgarity and meanness, that of fault-finding is the most easy and the most common. Who is there so weak, so dull, as not to be able to make another appear wicked, unamiable, or ridiculous, if he will watch his actions and be resolved to attribute them to bad motives?

It is easy to draw a charicature likeness of another: you have only to represent the prominent features, with a little absurd exaggeration, and any body sees at once the ridiculous resemblance. Thus a caricature of even a handsome person excites laughter: but it is a very poor vocation—this of draw

-----

p. 37

ing caricatures—because a very stupid person can succeed in it; because it is a species of lying, for it violates the truth and inculcates falsehood; because it cultivates bad habits in his who executes and him who sees the false picture; and because it wounds the feelings of the subject of the caricature, and does him as gross injustice as if you robbed him of his money; and because it stirs up enmity and strife in society.

The true art of the painter is to seize upon the agreeable expression of the person he would represent, and to portray it so that all will know it at once as a likeness. The art of doing this is a noble art, and it requires ability and genius to excel in it.

Now, these remarks may be fairly applied to moral painting: it is easy, in speaking of others, to draw caricatures of them and to make them seem ridiculous. i am afraid, it is because the thing is so easy

-----

p. 38

that it is so common. Why is so much of our conversation made up of uncharitable talk about our neighbours, companions—perhaps those we call our friends? Is it not because the heart is wrong and loves scandal—caricature—ridicule—and the tongue finds it easy to exercise itself in this way?

Perhaps my readers may think that they will become dull and uninteresting, if they only speak of pleasant things. It is not so, my dear young readers. Nothing can better show good sense—a good heart—good taste—good talents, than the habit of perceiving and pointing out the good qualities of others. Which shows the best taste—going forth into the fields to gather noxious weeds and offensive plants; or going forth to gather sweet-scented flowers and lovely blossoms? Which is most lovely—one who is addicted to making and exhibiting nosegays, gathered and grouped from the pleasant things in the characters of their friends; or one who is in the habit of treasuring up the unpleasant things they can discover in those around them, and retailing them for the poor compensation of a smile or a laugh?

-----

p. 39

To illustrate the advantages of dealing in the good things which we may see in others, if we will only seek for them, let me tell you a matter of fact. I have the pleasure to know a lady, who is one of the most agreeable, the most gifted, and the most famous in America, and though I have known her intimately for years, I never heard her say an unkind word of any living being!

This lady has written many books—some of prose and some of poetry, and her name is honoured as well in the Old World as the New; yet you cannot find in them a page of satire, or a sentence of misanthropy. All is charity—all is a display of the beautiful in nature and the lovely in character; she is enamoured of beauty and virtue wherever they dwell, and her books as well as her conversation are but exhibitions of that holy affection. What a glorious thing it is to have a heart to admire and a genius to display the loveliness which God has scattered over the landscape, and made to flourish and bloom in the human bosom!

Though I have said a good deal more than I intended on charity, still there is

-----

p. 40

much more to be said of it. The Bible tells us that it covers a multitude of sins, which means, that a person who has true charity will seek rather to hide than to display the faults of others.

Alas, how unhappy should we be, if God, who looketh on the heart, and sees all our motives, were not more kind and charitable to us, than we are to our fellow-men! If we would hope for mercy above, let us practise it here below.

-----

[p. 41]

CHAPTER VIII.

CHARITY.

History of the Two Seekers.

There were once two boys, Philip and Frederick, who were brothers. Philip waqs a cheerful, pleasant, good-natured fellow; he had always a bright smile on his face, and the mere sight of him made everybody feel an emotion of happiness. His presence was like a gleam of sunshine, peeping into a dark room—it made all light and pleasant around.

Beside this, Philip had a kind heart; indeed, his face was but a sort of picture of his bosom. But the quality for which he was remarkable was a disposition to see good things only in his friends and companions: he appeared to have no eye for bad qualities. If he noticed the faults, errors, or

-----

p. 42

vices of others, he seldom spoke of them. He never came to his parents and teachers, exaggerating the naughty things that his playmates had done. On the contrary, when he spoke of his friends, it was generally to tell some pleasant thing they had said or done. When he felt bound to notice another’s fault, he did it only from a sense of duty, and always with reluctance, and in mild terms.

Now Frederick was quite the reverse of all this. He loved dearly to tell tales. Every day he came home from school, giving an account of something wrong that had been done by his playmates, or brothers and sisters. He never told any good of them, but took delight only in displaying their faults. He did not tell his parents or teacher these things from a sense of duty, but from a love of telling unpleasant tales. And, what was the worst part of it all, was this: Frederick’s love of tale-bearing grew upon him, by indulgence, till he would stretch the truth, and make that which was innocent in one of his little friends appear to be wicked. He seemed to have no eye for pleasant and good

-----

p. 43

things—he only noticed bad ones: nay, more, he fancied that he saw wickedness, when nothing of the kind existed. This evil propensity grew upon him by degrees; for you know that if one gets into a bad practice, and keeps on in it, it becomes at last a habit which we cannot easily resist. A bad habit is like an unbroken horse, which will not mind the bit or bridle, and so is very apt to run away with his rider.

It was just so with Frederick: he had got into the habit of looking out for faults, and telling of them, and now he could see nothing else, and talk of nothing else.

The mother of these two boys was a

-----

p. 44

good and wise woman. She noticed the traits of character we have described in her sons, and while she was pleased with one, she was pained and offended on account of the other. She often talked with Frederick, told him of his fault, and besought him to imitate his amiable brother: but as I have said, Frederick had indulged his love of telling tales, till it had become a habit, and this habit every day ran away with him. At last the mother hit upon a thing that cured Frederick of his vice—and what do you think it was?

I do not believe that any of you can guess what it was that cured master Frederick. It was not a pill, or a poultice; no, it was a story—and as I think it a good one, I will relate it to you.

“There were once two boys,” said the mother, “who went forth into the fields. One was named Horace, and the other was named Clarence. The former was fond of anything that was beautiful—of flowers, of sweet odours, of pleasant landscapes. The other loved things that were hideous or hateful—as serpents and lizards—and his

-----

p. 45

favourite haunts were slimy swamps and dingy thickets.

“One day the two boys returned from their rambles; Horace bringing a beautiful and fragrant blossom in his hand, and Clarence bringing a serpent. They rushed up to their mother, each anxious to show the prize he had won. Clarence was so forward, that he placed the serpent near his mother’s hand: on which the reptile put forth his forked tongue, and then fixed his fangs in her flesh.

“In a moment a pain darted through the mother’s frame, and her arm began to swell up: she was in great distress, and sent for the physician. When he came, he manifested great alarm, for he said the serpent was an adder, and its bite was fatal, unless he could find a rare flower, for this alone could heal the wound. While he said this, he noticed the blossom which Horace held in his hand. He seized upon it with joy, saying—‘This, this is the very plant I desired!’ He applied it to the wound, and it was healed in an instant.”

But this was not the whole of the story.

-----

p. 46

“while these things were taking place, the adder turned upon the hand of Clarence, and inflicted a wound upon it. He screamed aloud, for the pain was very acute. The physician instantly saw what had happened, and applying the healing flower to the poor boy’s wound, the pain ceased, as if by enchantment, and he, too, was instantly healed.”

Such was the story which the mother told to her two sons. She then asked Frederick if he understood the meaning of the tale. The boy hung his head, and made no answer. The mother then went on as follows:

“My dear Frederick—the story means that he who goes forth with a love of what is beautiful, pleasant, and agreeable, is sure to find it: and that he who goes forth to find that which is evil, is also sure to find what he seeks. It means that the former will bring peace and happiness to his mother, his home, his friends; and that the latter will bring home evil—evil to sting his mother, and evil that will turn and sting himself. The story means that we can find good, if we seek it, in our friends, and that this good

-----

p. 47

is like a sweet flower, a healing plant, imparting peace and happiness to all around. The story means that we can find or fancy evil, if we seek for it, in our friends; but that, like an adder, this only wounds others, and poisons those who love to seize upon it.”

Frederick took the story to heart; he laid it up in his memory. When he was tempted to look out for the faults of his companions, and to carry them home, he thought of the adder, and turning away from evil, he looked out for good; and it was not long before he was as successful in finding it as his brother Philip.

-----

[p. 48]

CHAPTER IX.

CHARITY.

In the southern part of France is a large city called marseilles: here there once lived a man by the name of Guizon; he was always busy, and seemed very anxious to get money, either by his industry, or in some other way.

He was poorly clad, and his food was of the simplest and cheapest kind: he lived alone, and denied himself all the luxuries and many of the comforts of life.

He was honest and faithful, never taking that which was not his own, and always performing his promised; yet the people of

-----

p. 49

Marseilles thought he was a miser, and they held him in great contempt. As he passed along the streets, the rich men looked on him with scorn, and the poor hissed and hooted at him. Even the boys would cry out, “There goes old Skinflint.”

But the old man bore all this insult with gentleness and patience. Day by day, he went to his labour, and day by day, as he passed through the crowd, he was sluted with taunts, and sneers, and reproaches.

Thus time passed on, and poor Guizon was now more than eighty years of age. But he still continued in the same persevering industry, still lived in the same saving, simple manner as before.

Though he was now bent almost double, and though his hair was thin and as white as snow; though his knees tottered as he went along the streets; still the rude jokes and hisses of the throng pursued him wherever he went.

But, at length, the old man died, and it was ascertained that he had heaped together in gold and silver, a sum equal to forty thousand pounds. On looking over his

-----

p. 50

papers, his will was found, in which were the following words:

“I was once poor, and I observed that the poor people of Marseilles suffered very much for the want of pure, fresh water. I have devoted my life to the saving of a sum of money sufficient to build an aqueduct to supply the city of Marseilles with pure water, so that the poor may have a full supply.”

Let us be careful how we judge others uncharitably, in denouncing, ridiculing, persecuting those who live differently from what we do—who seem to us to be narrow-minded and selfish—it may be that we are doing them great injustice, and injuring those who are in reality far better than ourselves. let us, rather, be charitable, for this is always safe.

-----

[p. 51]

CHAPTER X.

CHARITY.

One evening as I was passing along a street in Boston (in America,) I saw a poor ragged fellow, known by the name of Simple Simon. He had in his face a look of melancholy, and his clothes bespoke at once poverty and neglect. He was in fact a harmless, helpless creature, having hardly common sense, and living for the most part upon charity.

-----

p. 52

As I came near him, a finely-dressed young man passed him by. According to his habit, Simple Simon held out his hand to the youth, as if asking for alms. The latter turned his head aside with unconcealed disgust, and making no other reply to the beggar than this look of aversion, went his way.

As I was curious to see the effect of this rudeness upon poor Simon, I went up to him, and after a little conversation, I spoke of the youth in a manner to draw out his feelings.

“You say he is a handsome fellow, and so he is,” said Simon: “and he is a good young man, too, for aught I know; but he cannot condescend to speak to me: and why should he? I am now a poor creature and unfit to be spoken to by one who wears a good coat and kid gloves, and is the son of a great man. Why should he speak to Silly Simon?”

“Then you know him, do you?” said I.—“Know him!—yes,” said the beggar, “and his father before him. His father was a rich man and president of a college. My father was poor, but still he wished to have

-----

p. 53

his children well educated; so he sent my brother Ben to the university. But things went ill with my father; and as the saying is—worse always comes behind to kick bad down hill. Still, Ben was a good scholar, and my father did not take him from the college, hoping and striving all the time to make things improve: so he got in debt to the college, for Ben’s instruction.

“Well, one day my father had a sheriff’s officer sent after him, and as he could not pay the debt, he was taken to prison. Now, I do not mind being sent to prison myself, for I am a poor good-for nothing. I have been sent there several times, and though I never knew what it was for, still it is all the same to Silly Simon. But my father was a sensitive man, and to be shut up in a stone room, where the air was damp and close, was a strange thing to him. He was a little nervous too, I believe, for it affected him very much. He had been respected by the world at large, and had spent his life in acts acknowledged to be beneficial to mankind: and now, to be confined as if he were guilty of some crime, and unworthy of breathing

-----

p. 54

the fresh air, and of holding intercourse with his fellow-men! all this turned his head. It affected him the more, that the blow came from the college which ought, as he said, to set examples of humanity.

A friend went to the president and begged him to let my poor father out of prison, but he pretended to know nothing about it, and refused to interfere. At last some friend, hearing of my father’s situation, paid the debt and he was released. But the affair sunk deep into his heart; and perceiving that the richer and more respectable members of society took part with the president; that the latter was kept in his place, and not only vindicated but cherished—while he was himself neglected and despised, because he had become poor and been put in prison—he lost his confidence in mankind and himself, and soon died of a broken heart.

“Misfortunes never come single you know—so, soon after my father died, poor Ben followed. I was left destitute, and there was no one to care for me. By and by I was taken sick of a fever: it settled on my brain, and left it at last in a terrible

-----

p. 55

state. I never could get it fairly cleared up, and all the better it is for me. If I had my senses, then the things of which I tell you would make me unhappy; but as it is, I am contented. I can see the president’s son pass by in scorn, and feel sorry for him; for, after all, I think it must give him more pain than it does me. Poverty is a sad thing, Mr. Parley, but there is something worse.”

“And what is that?”

“Selfishness,” said Simon; “that kind of selfishness which makes a man forget how others feel. I am poor, silly, as they call me,—but still, I never forget what is going on in the breasts of others. There are some men so proud, so lofty that they regard a great part of their fellow-men as little as we do worms and insects in our path. They stride proudly on, thinking that if any one is crushed beneath their mighty tread, it is because he gets in their way, and this is all they think or care about it. Now I am one of those worms and I have often been trod upon. I know the agony—the cruel agony which attends such cases; and I therefore feel for every human being who suffers. I

-----

p. 56

would not even tread upon a worm, if I knew it.”

I left the poor beggar with his words treasured in my heart: and I drew this lesson from his story,—that a beggar may still impart truth and wisdom; that under the garb of poverty, there may be something to respect and admire; that even seeming weakness has often a touching moral for those who will listen and learn; and that God sends down to the crushed bosom, in kindness and for consolation, that mantle of charity, which is even better than garments of purple and fine linen.

-----

[p. 57]

CHAPTER XI.

SELFISHNESS.

A dog and a cat were once sitting by a kitchen door, when the cook came out and threw several pieces of meat to them.

They both sprang to get it, but the dog was the strongest, and so he drove the cat away, and devoured all the meat himself. this was selfishness; by which I mean, that the dog cared only for himself. The cat wanted the meat as much as he did; but he was the strongest, and so he took it all.

But was this wrong? No,—because the dog knew no better. The dog has no idea of God, or of that beautiful golden rule of conduct, which requires us to do to others as we would have them do to us.

-----

p. 58

Dr. Watts says,—

“Let dogs delight to bark and bite,

For God hath made them so;

Let bears and lions growl and fight,

For ’tis their nature too.”

But children have a different nature, and a different rule of conduct. Instead of biting and fighting, they are required to be kind and gentle to one another, and to all mankind.

Instead of being selfish, like the dog, they are commanded to be just and charitable; by which I mean, that they should always give to others what is their due, and also give to others, if they can, what they stand in need of.

If a child snatches from another what is not his, he is selfish and wicked. If a child tries in any way to get what belongs to another, he is selfish, and is in his heart a thief or a robber. Selfishness is caring only for one’s self. It is a very bad thing, and every one should avoid it. A selfish person is never truly good, or truly happy, or truly beloved, when his character is known.

How miserable should we all be, if every person was to care only for himself! Suppose children and grown-up people, were all to be as selfish as cats and dogs; what constant fighting there would be among them.

-----

[p. 59]

CHAPTER XII.

THE VALUE OF CHARACTER.

I shall relate a fable to you, which shows what a bad thing it is to have a stain on one’s character, and how it may sometimes subject one to be punished for what one has not committed.

A wolf once made complaint that he had been robbed, and charged the theft upon his neighbour the fox. The case came on for trial before a monkey, who was justice of the peace among the quadrupeds in those parts. The parties did not employ lawyers, but chose to plead their cause themselves. When they had been fully heard, the judge,

-----

p. 60

assuming the air of a magistrate, delivered his sentence as follows:

“My friends and neighbours,—I have heard your case, and examined it attentively; and my judgment is, that you both be made to pay a fine; for you are both of bad character, and if you do not deserve to be punished now, it is likely you will deserve to be so very soon.

“That I have good grounds for this decree, is sufficiently evident by the fact, that Mr. Wolf’s jaws are even now stained with blood, and I can see a dead chicken sticking out of Sir Fox’s pocket, notwithstanding the air of injured innocence which he wears. And beside, one who gets and evil reputation should think it no hardship if he is occasionally made to suffer for a crime he did not commit.”

This fable teaches us to beware of an evil reputation; for it may cause us to be punished for the misdemeanors of others. Thus, if a person gets the character of a liar, he will not be believed when he tells the truth; and when a theft is known, it is of course laid to some one who has been caught in stealing before.

-----

[p. 61]

CHAPTER XIII.

JUSTICE.

Justice is rendering to others what is their due, and not only requires of us fair dealing in matters of property, but it requires of us fair dealing in all the intercourse of life. Every kind of advantage we take of others, even in the smallest things, bespeaks the spirit of injustice, and is to be condemned.

The child that snatches away another’s toys; the shrewd and knowing boy that overreaches his more simple fellow in a barter of penknives; the person who gives currency to a scandalous tale; all these are guilty, at the bar of conscience, of the crime of injustice.

One of the most common and yet most mischievous kinds of injustice is that of putting false and injurious constructions on the actions of others. How often do we hear people say,—such a one is proud—that man

-----

p. 62

is seeking display—this one is puffed up with conceit! In most cases these imputations are false, and therefore unjust. How wicked then is this practice of evil speaking, as it does much harm and no good!

If I were to draw the portrait of a truly noble character, I should make justice the basis of it. A just person must have many virtues; he must be a lover of truth, a lover of honesty, a lover of what is right. He must despise falsehood, trick, deception and fraud of any kind. Let any of my readers who desire to adorn their souls with a noble attribute, cultivate justice, not only in deeds, but in words, thoughts, and feelings. Let them be just even in the little arguments that arise around the fireside, in all the familiar intercourse, sports, pleasures, and controversies of the field, the high road, and the schoolroom. Let them establish the habit of being just, even in trifles: let them cherish the feeling of justice as they would the dearest friend.

-----

[p. 63]

CHAPTER XIV.

HUMILITY.

This is a humble virtue, yet a most lovely one. Jesus Christ has said that the poor in spirit—the humble—the meek—are blessed, for they shall see God. What a mighty preference! what a noble promise! Humility is, therefore, a pearl of great price, and is really better than money and lands and merchandise. It is not the rich, not the haughty, the proud man, but the humble one that is to see God.

Humility is often of great advantage in life; for when the proud are resisted and crushed, the meek and lowly are frequently

-----

p. 64

permitted to pass on, unheeded perchance, but yet unhurt. The fable of the Oak and the Reed will illustrate this.

An oak stood on the bank of a river, and growing at its foot was a reed. The oak was aged, and its limbs were torn away by the blasts of years; but still it lifted its head in pride, and looked down with contempt upon the reed.

At last there came a fearful tempest. The oak defied it, but the reed trembled in every fibre. “See,” said the oak, “the advantage of strength and power; see how I resist and triumph!”

While it spoke thus, a terrible rush of the gale beset it, its roots gave way, and it fell to the earth with a tremendous crash. But while the oak was thus destroyed in its pride, the humble reed bowed to the blast, and, when the storm was over, it arose and flourished as before.

-----

[p. 65]

CHAPTER XV.

MILDNESS.

The Sun and Wind once fell into a dispute as to their relative power. The Sun insisted that, as he could thaw the iceberg, and melt the snows of winter, and bid the plants spring out of the ground, and send light and heat over the world, he was the most powerful. “It may be,” said he to the Wind, “that you can make the loudest uproar, but I can produce the greatest effect. It is not always the most noisy people that achieve the greatest deeds.”

“This may seem very well,” said the

-----

p. 66

Wind; “but it is not just. Do I not blow the ships across the sea, turn windmills, drive the clouds across the heavens, get up squalls and thundergusts, and topple down steeples and houses with hurricanes?”

Thus the two disputed, when, at last, a traveller was seen coming along; and they agreed each to give a specimen of what he could do, and let the traveller decide between them.

So the Wind began, and it blew lustily. It nearly took away the traveller’s hat and cloak, and very much impeded his progress: but he resisted stoutly. The Wind having tried its best, then came the Sun’s turn. So he shone down with his summer beams, and the traveller found himself so hot that he took off his hat and cloak, and almost fainted; he soon decided that the Sun had more power than the Wind.

Thus our fable shows that the gentle rays of the Sun were more potent than the tempest; and we generally find in life that mild means are more effective, in the accomplishment of any object, than violence.

-----

[p. 67]

CHAPTER XVI.

CANDOUR.

Candour is that state of heart which disposes a person to see and confess the truth. It belongs to all real lovers of truth. Without it no person can be honest, just, sincere, or faithful.

It is a most important virtue, for it lies at the very root of goodness, and is indispensable to rectitude of conduct and real force of character. Candour is opposed to prejudice: while prejudice would blind the mind, candour would give it clearness of perception. Candour is like a clear atmosphere, enabling us to see objects distinctly: prejudice is like a wrinkled glass, that would distort the objects which are seen through it. Candour would wipe clean the spectacles of the mind: prejudice would obscure them, or perhaps paint them over with false and decpetive images.

-----

p. 68

Candour is opposed to many other vices, all of which are unfriendly to truth. Disingenuoousness, which would conceal the truth by some deceptive veil; artifice, which would make falsehood pass for truth; improper concealment, which would hide the truth where it is required; moral cowardice, which makes one fear the truth; these mean yet dangerous and besetting vices are all opposed to candour. If any of my readers feel that any of these sad diseases are in their souls, let them administer candour, for this is a certain cure for them all.

Candour is necessary to those who would be wise, for wisdom consists in knowing the truth; and how can one see and know the truth, if he is blinded by an imperfect vision, or misled by an atmosphere that presents objects either falsely or obscurely?

Candour is not only thus useful and necessary, but it is a most delightful grace in character. No person can be amiable without it: no person can have sincere friends without it; no person can possess true beauty of soul without it. The face is usually an index to the soul; it is a sort of mirror re-

-----

p. 69

flecting the passions that are within. If a person is destitute of candour, destitute of a love of truth, and therefore a lover of falsehood, the face is very apt to tell the sorry tale. If, on the contrary, a love of truth is in the heart, it is likely to shine forth in that which we call the expression. Think of this, my gentle friends—think of this; and if you would have true beauty of face, take care to make candour an habitual tenant of the soul.

-----

[p. 70]

CHAPTER XVII.

PREJUDICE.

Prejudice is a false judge that comes into the mind, and induces it to pronounce sentence of condemnation, either without inquiry, or in opposition to truth and knowledge. It is a thief that steals truth and candour from the soul, leaving it in the possession of malice, envy, or falsehood—whichever may make the strongest appeal to self-love or selfishness.

If there were in the place where we live some horrid monster, as, for instance, a fierce lion that infested the path of the traveller, or an insidious serpent that stole

-----

p. 71

around our footsteps and stung us with its deadly poison, how soon would the whole mass of society be in arms to destroy the enemy. Yet prejudice is more hurtful to the peace of mankind; it is a thousand times more destructive of human happiness than such a monster or such a reptile as we have supposed. Iit is a snake in the grass, that poisons our souls unseen: it is a spider that weaves its fatal web in the chambers of thought, and carries on its work of destruction in silence and secrecy.

Prejudice influences us without our being fully aware of its presence; and after we have got into the habit of acting according to its dictates, we often think that we are doing right when we are doing very wrong. I shall endeavour, by a few tales and incidents, to show some of the ways in which we are influenced by prejudice.

Prejudice Conquered.

Several children were one day passing by a church, when they noticed a litt girl, sitting on a stile. One of the elder

-----

p. 72

girls of the group, whose name was Lydia Flair, thus spoke to the girl upon the stile.

“Well, Miss Gridley, pray what are you doing there?”

The girl looked up with some surprise at this rude speech, but answered mildly,—“Oh, I am sitting here, because it is so pleasant all around.”

“Very sentimental, indeed!” said Lydia; and the little party moved along.

“Do you know Grace Gridley?” said Ellen Lamb, one of the party, to Lydia.

“To be sure I do, and I hate her,” was the reply.

“Hate her!” said Ellen; “that is a strong expression,—and why do you hate her?”

-----

p. 73

“Oh, I do not know, exactly!” said Lydia; “but she goes to church three times on a Sunday, and associates with people that pretend to be so pious, and so much better than other people.”

“You hate her, then, because she goes to church so often?” said Ellen.

“Why that is not all: she has such a prim precise air; there is always something about her so correct, that I feel uneasy where she is. Beside, everybody says she is good and handsome, and all that. I hate people that are always praised by everybody, for I believe they are no better than other people, and are only more deceitful.”

“You feel, perhaps, a sort of envy, and this may lead you to see their conduct in a false light. Envy and prejudice, Lydia, will often deceive us. Now I know Grace Gridley, and I think her as different as possible from what you think her to be. So far from being precise and hypocritical, she is one of the most frank, sincere, and kind-hearted creatures that I ever knew. I wish you would allow me to make yoou better acquainted with her.”

-----

p. 74

“No, no—I know enough of her: I could never like her.”

“You would like her—you could not help it. Come! go back with me, and let us see a little more of Grace.”

Lydia permitted herself, though very reluctantly, to be led back to the place where Grace was sitting. She had not only a vague dislike of her, from the fact that Grace went to church so often, and was one of those whom her own parents were in the habit of calling stiff, over-righteous, and bigoted; but she had now been impertinent to Grace, and as we are apt to dislike those whom we have injured, Lydia had a new motive for prejudice against her. However, the party were soon brought back to the stile, and grace was induced to join them. She made herself agreeable to all; and before Lydia parted, the first steps were taken toward a better acquaintance. The final result of this was, an entire change of feeling and opinion, on the part of Lydia, toward Grace.

A few months after the scene we have described, the following conversation took place between Ellen Lamb and Lydia Flair.

-----

p. 75

E. So you confess that you like Grace Gridley, after all?

L. Why I cannot help liking her; she is as different as possible from what I conceived she was: I thought her bigoted,—but I find, although she is very pious, and very firm in her principles, that her heart is overflowing with kind and generous feelings. I deemed her deceitful,—but she is frankness itself. I expected that she would be severe and censorious—but she is the most considerate and charitable creature in the world. Although very handsome, yet she seems not to care anything about it. I never saw any one that I liked so much, and if I had committed a fault, I would sooner go to her, confess it, and ask her advice in the matter, than to any other person.

E. I am glad to hear you say that, for it is no more than just. But, my dear Lydia, I wish you to reflect one moment, and then tell me what it was that made you once dislike Grace so much, and do her such injustice?

L. I have told you, I believe; I told you

-----

p. 76

she associated with stiff, over-pious people, and I supposed she must be stiff and shining herself.

E. In other words, you had a prejudice against her; you had a dislike, without any just reason. Let us take care of such prejudices, my dear Lydia! and allow me to ask if you are not indulging the same unreasonable feeling, when you speak of Grace’s friends and associates, as stiff and whining and hypocritical?

L. Oh no—at least, I think not.

E. And yet, Lydia—you do not know these people. Is not this in itself wicked? Observe how this false reasoning misled you in respect to Grace Gridley. It led you to call her bigoted and hypocritical—whereas, you now admit, that she is the reverse of all this. Only think of the awful injustice you did her;—you tried to steal away her good character, and committed that worst of all cruelty—you gave her a bad name.—

Here Lydia, stung to the heart with a sense of her error, burst into tears: she was thoughtless, but not hardened, and had only done as too many do; she had indulged

-----

p. 77

prejudice—and thus had been guilty of great wickedness. She had done thus, in partial ignorance of her sin, for as I have said prejudice is like a spider—it creeps slily into the mind, and takes possession of it unseen, and often hangs it over with dismal cobwebs, which are invisible to the owner of the tenement, though plain enough to the eye of God and man.

The Story of Aristides.

There is a story handed down us in the history of ancient Greece, which shows us that prejudice may even lead ignorant and wrong-minded people to dislike and oppose excellence.

There was in Greece, a man named Aristides, so celebrated for his integrity, his honesty, his love of truth and his uprightness, that he was called Aristides the Just. Well, in consequence of a false charge brought against him by some of his enemies, whose unjust proceedings he had opposed, the people of Athens were about to banish him from the city, but before this

-----

p. 78

could be done, the vote of every citizen was to be taken.

It was the custom for the Greeks in those days to vote for the banishment of a person by handing in tiles, or shells, on which the name of the accused was inscribed. An ignorant fellow, at the time of voting, seeing Aristides near, and not knowing him, but judging him to be a man of education, and capable of writing, went up and asked him to write the name of Aristides on his tile.

Aristides did as he was requested, and having handed the tile to the man, asked him, as a matter of curiosity, why he wished to banish Aristides. “Because,” said the freeman, “I am tired of hearing him called the Just.”

Here then, we see that a man, even acting in the high and responsible capacity of a freeman, indulges an unreasonable dislike, a prejudice,—he even allows a hatred o[f] excellence to influence him, when he is exercising a trust which involves the happiness of the whole community.

-----

p. 79

Truth Triumphant.

It sometimes happens that people living in the same town or village, without any good reason, contract a dislike of each other, and when they meet scarcely speak to each other: they are cold and distant, and by degrees get into the habit of thinking and speaking ill of each other.

One day as john Sawyer and Allen Highsted, both of whom lived in the village of Tintonex, met each other,—the former addressed the latter with a pleasant salutation, which was received with a cold look and a silent tongue. When one of his companions, Seth Mead, asked Allen why he treated Johnthus, “I do not like him,” was the reply.

“And why do not you like him?” said Seth.

“Because I do not,” says Allen; “and what is more—because I will not.”

“But this is unreasonable,” said the other.

-----

p. 80

“It may seem so—yet I have my reasons[,]” said Allen. “I think he is an impudent upstart.”

“Indeed! Are you acquainted with him?”

“No, and I do not wish to be: he is in a different condition of life from what I am; his father is a shopkeeper, and mine is a merchant. How should we have any intercourse? We cannot feel alike; we cannot live alike. Our manners, our tastes, our pursuits, our associates must all be dissimilar. Beside, he is a mean-spirited, narrow-minded fellow.”

“You were never more mistaken, Allen Highsted—never more in your life. John is a frank, honest, noble-minded fellow: and though his father is a shopkeeper, the boy is as well-bred, and has as good manners as any other in the village. Indeed, I think he is a pattern of good manners and right feelings. My father is, as you know, a man of large fortune; he has been well educated, and has seen the best society in this and other countries; and he thinks very highly of John’s father, and he encourages me to associate with John.”

-----

p. 81

“Well, you can do as you like—but I hate the fellow.”

“And will you indulge a hatred without reason?”

“No—I have reason for what I say and feel. John dislikes me, and takes every opportunity to say things against me.”

“Do you know this?”

“I know it as well as I wish to.”

“Can you cite an instance?”

“Yes—no longer ago than yesterday, in that affair of Lacy’s; I have reason to suppose that he caused me to be suspected of frightening the child into fits, about which there was such a clamour.”

“Well, what reason had you to suppose so?”

“Why, it is just like him; beside, I was suspected, and how should that have happened if he did not bring it about?”

“Let me tell you the truth, Allen. You were suspected, because you were seen near the place about the time the thing happened. I was at Lacy’s house last evening, and there were several people there talking about it. It was said that you frightened the child, but John Sawyer defended you

-----

p. 82

bravely: if he had been your brother, he could not have spoken of you more kindly. There were some evil-minded persons there, who knew that you had treated John ill, and they tried to make him take revenge of you, by helping on the suspicion against you. But he was above it all, and believing you innocent, he was too noble, too just, to try to make people think you guilty.”

“Indeed!—indeed!”—said Allen, reddening deeply; “is this so? How wicked—how cruel, then have I been! Forgive me, pray forgive me, my dear fellow.”

“I forgive you with all my heart,” said Seth;—“I have, indeed, nothing to forgive; but I shall be most happy to see you dismiss such a prejudice as you have indulged toward John Sawyer: he is really a fine fellow, and worthy of your esteem.”

“I believe it—I know it,” said Allen; “and I fear that I have had a secret consciousness, all the time, that I was doing him wrong. I tried to think ill of him, and I spoke ill of him, only because I did not know him, or because I felt that his excellence was a kind of reproach of me. I had treated him ill, too, on many occasions, and

-----

p. 83

being conscious of this, I wished to excuse my injustice by making him out a bad fellow: so I took a malignant and satirical view of all he did, and tried my ingenuity to prove myself just and right. But, my dear friend, I am cured of this weakness for ever. I will go this instant to John, and make him a due apology for my rudeness and unfairness.”

—

I hope these sketches will be sufficient to show my readers some of the most common forms in which prejudice operates, and how it frequently contrives to cheat and mislead mankind. Let us all guard against it as a great enemy to our present and future peace. It is a fierce and malignant tyrant, always seeking dominion over us, and when once enshrined in the heart, it is difficult to resist its influence or check its authority.

All those who desire to be free-minded, fair-minded, just and true, should strictly examine every personal dislike they feel: they should be careful to analyse it—see upon what it rests—and if it be unfounded, if it be but a prejudice, let them cast it out if they would not harbour an evil spirit in the heart.

-----

[p. 84]

CHAPTER XVIII.

MERCY.