Peter Parley’s Story of the Trapper, by Samuel Griswold Goodrich (Boston: Watt & Dow, 1829)

-----

[front cover]

-----

[inside front cover]

[A young owner pasted this label into the book before it was resewn. “Louisa B Whites Book” is written on the fly leaf.]

-----

[frontispiece]

PETER PARLEY TELLING STORIES.

-----

[title page]

OF

THE TRAPPER:

ONE OF PARLEY’S WINTER EVENING TALES.

———

BOSTON:

[illegible]

-----

[copyright page]

District Clerk’s Office.

BE IT REMEMBERED, that on the 24th day of October, A. D. 1829, in the fifty-fourth year of the Independence of the United States of America, SAMUEL G. GOODRICH, of the said district, has deposited in this office the title of a book, the right whereof he claims as proprietor, in the words following, to wit:

Peter Parley’s Winter Evening Tales.

In conformity to the act of the Congress of the United States, entitled ‘An act for the encouragement of Learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned; and also to an act, entitled ‘An act supplementary to an act, entitled, “An act for the encouragement of learning by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies during the times therein mentioned;” and extending the benefits thereof to the arts of designing, engraving, and etching historical and other prints.’

Clerk of the District of Massachusetts.

BOSTON:

Waitt & Dow,

Print.—122 Washington Street.

-----

[blank page]

-----

[illustration]

-----

p. 5

THE TRAPPER.

I suppose you have heard of Lake Superior. It lies several hundred miles northwest of Boston. It is an immense sheet of water with many islands in it. The shores are in some parts wild and rocky, but the islands in summer are very green and beautiful.

This great lake is nearly surrounded by forests. There are no towns, and no white people there, but the woods are inhabited by wild beasts of various kinds, and tribes of Indians.

The wild animals are deer, of which there are a great many. Moose, an animal as tall as a horse, with large branching horns, buffaloes which are as big as oxen, beavers larger than a cat, with very soft fur, of which hats are made. Besides these there are wolves, foxes, martens, otters, and other

-----

p. 6

creatures whose skins are valuable for the fur.

The Indians who live around Lake Superior, reside sometimes in one place and sometimes in another. Their houses or wigwams consist of skins supported by sticks, their shape being somewhat like that of a sugar loaf. These houses are very easily moved, and accordingly the Indians wander about from place to place as they see fit.

The chief occupation of the Indian men is hunting. The women attend to matters about the house. The men sometimes use guns, and sometimes bows and arrows. Such is their strength and skill in the use of the bow that they will send an arrow quite through the body of a buffalo, and kill him dead. They eat the flesh of the animals they kill. Of some of the skins they make clothing; the rest they sell to white men who go to trade with them.

Sometimes there are parties of white men who go up into the wild regions around lake Superior for the purpose of catching

-----

p. 7

beaver, martens, foxes and other animals. These people generally use traps for catching these animals, and therefore they are sometimes called trappers. It is of one of these trappers that I am now going to tell you.

This man’s name was David Pelt. He went several successive seasons up into this country for the purpose of getting furs. He was a very brave hardy man, and he succeeded very well. Every year he caught a great many beavers, martens and other creatures; their skins he took sometimes to Detroit and sometimes to Montreal, where he sold them and thus obtained a good deal of money.

Now I must tell you that David Pelt had a wife and child, and they lived in Montreal, while he went on his trapping expeditions. His child was a fine boy about twelve years old. One winter while Pelt was gone his wife died. It was several months after that he returned. He had not heard the sad news. Expecting to see his wife and boy, he went to his comfortable

-----

p. 8

little house in Montreal. But the window shutters were closed and the door was locked. He was anxious and alarmed, and being a strong man he burst in the door. But there was no living thing there. All was silent and desolate; not even the old dog and the gentle cat were to be seen.

David now went out of the house and went to one of the neighbors to inquire the meaning of all this. There, for the first time, he learnt that his wife had died four months before. He also learned that his son, to whom he had given the name of Martin, was living at the house of a friend who had kindly taken care of him after his mother’s death. The poor man was quite broken hearted, he sent for his son and then went to his own house. Here he staid but a few months. He appeared very sad, and as the trapping season approached, he set out with his son Martin for the border of the great Lake. Martin trotted away by the side of his father, and being fond of every thing that was new, he was delighted with the journey. At length they reached the

-----

p. 9

neighborhood of the Lake, and there the trapper determined to remain. Accordingly he built himself a tent, or wigwam of skins, and here he and his son slept at night very comfortably. During the day they were occupied in hunting wild animals and in attending to their traps.

Now you must understand that the trapper and his son were many hundred miles from any white people. They were alone in the wilderness with no friends near them. There were scattered tribes of Indians round them, but hitherto David had met with few of them, and those had not offered to do him any harm.

But notwithstanding the lonely situation of the trapper he seemed to be content. He was always grave and serious, nor could even the playfulness of his son induce him to smile. The boy amused himself as well as he could; he made little traps and caught some mice and small birds. He made bows and arrows and grew very expert in the use of them. Sometimes he would fish in the Lake which was near, and

-----

p. 10

as he grew more and more adventurous, he at length climbed the rocks that hung over the water in search of the eggs of wild birds that frequented those places. Sometimes he would wander to a considerable distance, but he was never absent any great length of time, and therefore his father had no anxiety on his account.

But I am now come to a painful part of my story. One day the trapper left his son in the tent and went to visit the traps. He was gone longer than usual, but when he came back his son was not there. He waited some time. But the boy did not come. He then went out of the tent and called his son with a loud voice, but he received no answer. He now became very anxious, and went to the top of a little hill, hoping that he might see him. But he was no where to be seen. He went into the woods and called him aloud. This was all in vain. He then went to the top of a cliff that overhung the water where he knew his son sometimes went to amuse himself. The dreadful idea came across his mind

-----

p. 11

that the boy had probably fallen from the rocks into the water and was drowned.

So strongly had this fear taken possession of his mind that when he arrived at the top of the cliff, he hardly dared to look over upon the water, fearing that he should see the body of his drowned boy floating upon the waves. Yet he did look down upon the Lake, but saw there no trace of the object of his search.

It was now night, and the distressed father went back to his little tent. He did not attempt to sleep that night. Although he repeatedly heard the wolves howling around him, he made several excursions into the woods in various directions. Fearing that his son was wandering in the woods alone and lost, he called again and again, and his deep distress adding to this strength, he made the wide forest resound with his call.

But the morning came, and the trapper saw not his son; all that day he spent in unavailing search; another night followed, and at length a week had passed, and the agonized father was still alone. He had

-----

p. 12

been obliged to adopt the belief that his boy was dead; but how had he died? Had he fallen from the rocks and been drowned? Had he wandered into the wilderness got lost and died for want of food? Or had he fallen a prey to some wild beast? Or had he met with the savages, and had they carried him into captivity? Or had they taken his life?

All these questions and many more he put to himself, but he could only answer them by conjecture. In a state of total uncertainty he was obliged to admit the painful conclusion that he should never see his boy any more.

He determined however to remain on the spot a short time longer, and then go among the Indians and see if he could not learn some tidings respecting his boy. This latter project he put in execution about a week afterwards. He went among the Indians and met with various adventures. Some of these were very interesting, but I cannot tell you of them now. Having spent several months in his inquiry, and all to no

-----

p. 13

effect, he at length determined to return to Montreal.

He had set out upon his return and progressed a considerable way on his journey, when one evening he was approaching an Indian village. He saw the wigwams in a little open plain at the distance of half a mile.

He stopped a moment and was hesitating whether he should go to the village and seek a lodging there, or whether he should avoid it altogether. Before he had made up his mind, he heard the cry of some one in distress at no great distance. He instantly ran toward the spot from whence the sound proceeded, and there he saw an Indian boy about twelve years old beset by a wolf. The boy had nothing to defend himself with, but with admirable courage he stood facing the howling animal, which though daunted with the bold bearing of the boy, was still close to him barking and snapping at him, and evidently on the point of fastening his teeth in his flesh.

-----

p. 14

The trapper ran with all his speed toward the boy, but before he could reach him, the wolf caught hold of his leg, and drew him to the ground. The boy grappled with him, but had not the trapper arrived at the instant he did, it is probable he would have killed the boy.

But David, as I have said before, was a powerful man. He instantly seized the wolf by one of his hind legs, drew him off from the boy, and swung him round, bringing his head against a tree with such violence, as to kill him with the blow.

The poor boy was considerably wounded, and could not walk. David took him up and carried him to the village. He soon found where the boy’s parents lived, and carried him to their wigwam. The boy told the story to his parents, and the grateful Indians were anxious to show hospitality to the white man who had saved their son. So they invited him into their wigwam, and they set before him some meat to eat. He was sitting on the ground with his supper before him, when a boy entered the wigwam

-----

p. 15

with a dress like that of the white people. It was somewhat dark, but the trapper started to his feet and laid hold of the boy, imagining that he saw in him a resemblance to his long lost son. He drew him instantly to the door of the tent, and the light fell upon the boy’s face. All doubt was instantly dissipated. It was indeed his boy, his long lost boy.

I need not stop to tell you of the happiness of both the father and son, but I must tell you how little Martin fell into the hands of these Indians. He had gone one day to hunt bird’s eggs upon the cliff that hung over the lake. He was near one hundred feet above the water, when his foot slipped, and he fell into the waves. It chanced that an Indian was at that moment near the spot in his canoe. He saw the boy fall, and took him out of the water. He was however stunned with the fall, and the Indian carried him away in a state of insensibility. It was more than a fortnight before he entirely recovered his recollection, and the Indian had carried him a distance of more than one

-----

p. 16

hundred miles to the village, where his father found him, as I have told you above.

Little Martin was a great favorite in the Indian village. The Indian who saved his life, was particularly fond of him, and he was very loth to let his father take him away. But the trapper had saved the life of the Indian’s boy, and he could not refuse to restore the white boy to his father.

The next day, the trapper and his son set out on their journey, and arrived safely at Montreal, and there my story must end.

-----

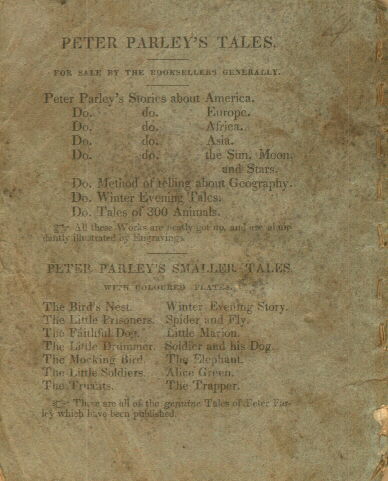

[back cover]

PETER PARLEY’S TALES.

FOR SALE BY THE BOOKSELLERS GENERALLY.

Peter Parley’s Stories about America.

[Peter Parley’s Stories about] Europe.

[Peter Parley’s Stories about] Africa.

[Peter Parley’s Stories about] Asia.

[Peter Parley’s Stories about] the Sun, Moon, and Stars.

[Peter Parley’s] Method of telling about Geography.

[Peter Parley’s] Winter Evening Tales.

[Peter Parley’s] Tales of 300 Animals.

All these Works are neatly got up, and are abundantly illustrated by Engravings.

WITH COLOURED PLATES.

The Bird’s Nest.

The Little Prisoners.

The Faithful Dog.

The Little Drummer.

The Mocking Bird.

The Little Soldiers.

The Truants.

Winter Evening Story.

Spider and Fly.

Little Marion.

Soldier and his Dog.

The Elephant.

Alice Green.

The Trapper.

These are all of the genuine Tales of Peter Parley which have been published.