A Mid-Century Child and Her Books, by Carolyn M. Hewins (New York: Macmillan Company, 1926)

-----

[frontispiece]

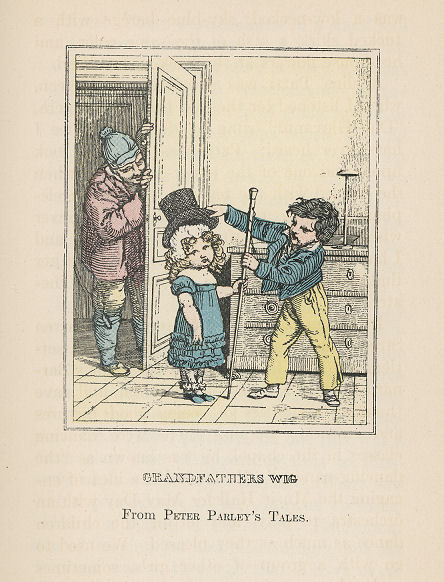

From Peter Parley’s Tales.

[Text:]

PETER PARLEY’S TALES.

[woman, three children, & toys]

S. G. GOODRICH & CO., BOSTON.

-----

[title page]

CHILD

AND HER BOOKS

CAROLINE M. HEWINS

“A Traveler’s Letters to Boys and Girls”

“A Booklist for Boys and Girls”

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1926

All rights reserved

-----

[copyright page]

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

——

Set up and electrotyped

Published November, 1926.

BY THE CORNWALL PRESS

-----

p. v

“Ever since the Winter’s evening when I made my first acquaintance with that delightful place,” writes Anne Thackeray Ritchie in her introduction to Cranford, “it has seemed to me something of a visionary country home which I have visited all my life long (in spirit) for refreshment and change of scene. I have been there in good company. ‘Thank you for your letter,’ Charlotte Brontë writes to Mrs. Gaskell. ‘It was as pleasant as a quiet chat, as welcome as spring flowers, as reviving as a friend’s visit; in short, it was very like a page of Cranford’.”

The copy of Cranford from which I quoted, with its delicately tinted drawings by Hugh Thomson, was a Christmas gift from Caroline Hewins in one of the early years of a friendship singularly rich in intimate associations with children and in the discovery of new and old books that children like. There is a likeness between Lady Ritchie’s picture of Cranford and my own feeling for Miss Hewins’s office in the Hartford Public Library. No “lofty pleasure-dome in Xanadu” did she rear for her dear friends, the books of her choice, but with the touch of a born magician she transformed an ordinary library room into a spacious hall of enchantment worthy of the mid-century child who fell in love with The Alhambra at the age

-----

p. vi

of ten. At home anywhere in the world, in this enchanting room one finds Caroline Hewins nearest to all she loves best and no one, child or grown-up who has visited her there will ever be the same again. Miss Hewins may have been reading or writing at her desk, she may have been solving a problem requiring hours of patient research and a sure sense of the latest authoritative statement, or again she may have been reading aloud,—the story of Persephone, if it was springtime,—or The Man of Snow, if it was near Christmas. Whatever she might be doing appeared in that setting quite the most fascinating thing in the world. Here are the books of her childhood from which she has brought forth a package to share with the readers of this little book just as she has so often shared them with groups of librarians and their friends in distant cities and towns as well as those of Connecticut. To hear Miss Hewins recite Pete[r] Piper[’s] Alphabet is something to remember. “It is my one parlor trick” she remarked characteristically when asked to repeat it in the children’s room of the New York Public Library at the opening of the annual holiday exhibition of children’s books. Needless to say it called forth tumultuous applause and every one went away determined to learn it. Here at last it is bound up with happy recollections of a delightful childhood.

Anne Carroll Moore.

New York City,

Hallowe’en, 1926.

-----

[p. vii]

PART I

Her Books … 49

-----

[p. viii blank]

-----

p. ix

Colored title-page from “Peter Parley’s Tales.” S. G. Goodrich & Co., Boston … Frontispiece

Title-page decoration from “Lilliput Levee.” Alexander Strahan, London, 1864 … 2

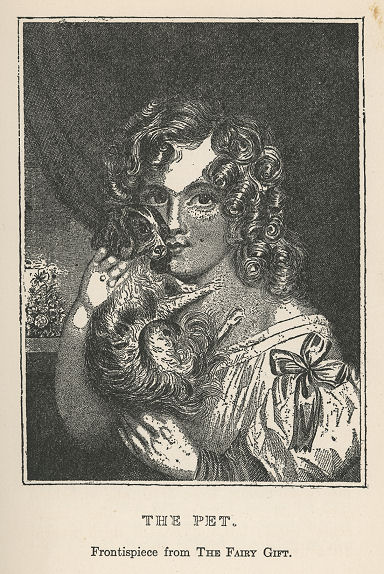

The Pet. Frontispiece from “The Fairy Gift.” Edward Dunigan, New York … 9

Decoration from “Mother Goose’s Nursery Rhymes,” Old Style. McLoughlin Bros., New York … 15

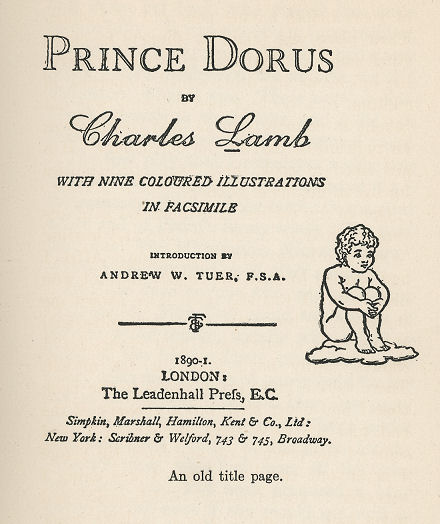

Title-page from facsimile edition of “Prince Dorus,” by Charles Lamb, first published by M. J. Godwin, London, 1811 … 21

Christmas Eve. From “Youth’s Keepsake,” Christmas and New Year’s Gift for Young People. William Crosby & Co., Boston, 1841 … 25

Grandfather’s Wig, illustration in color from “Peter Parley’s Tales.” S. G. Goodrich & Co., Boston … Facing 28

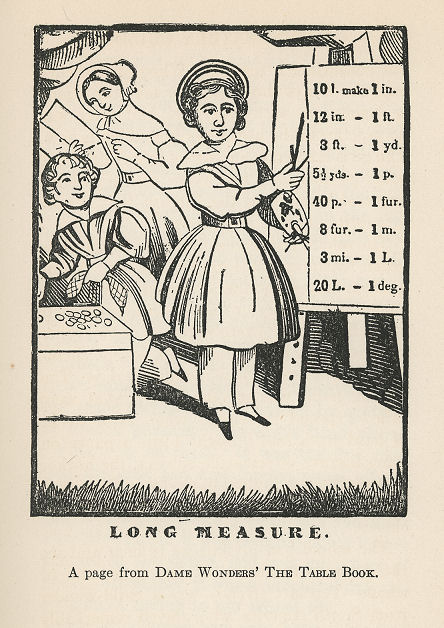

Long Measure. A page from Dame Wonder’s “The Table Book.” McLoughlin Bros., New York … 33

Little Boy and Hoop. A Decoration from “Grandmamma’s Book of Rhymes for the Nursery.” William Crosby & Co., Boston, 1841 … 37

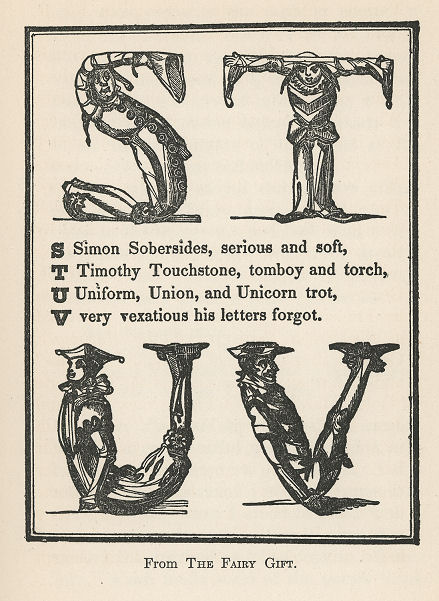

A page from “The Funny Alphabet,” found in the Fairy Gift. Edward Dunigan, New York … 41

Decoration from “Prince Dorus,” by Charles Lamb, first published by M. J. Godwin, London, 1811 … 48

-----

p. x

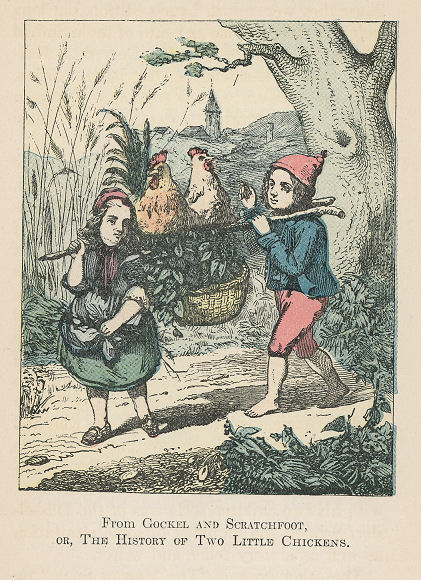

Illustration in color from “Gockel and Scratchfoot; or, The History of Two Little Chickens,” by G. Sus … Facing 52

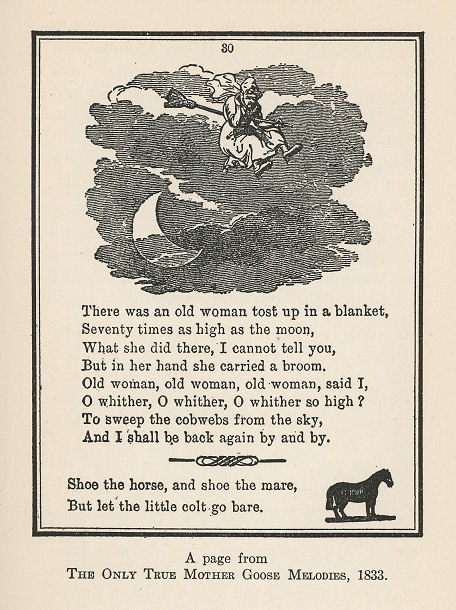

A page from “The Only True Mother Goose Melodies,” originally published in 1833 by Munroe & Francis … 55

Decorations from Beechnut; A Franconia Story,” by Jacob Abbott. Harper & Bros., New York, 1850:

“The Cocoa-man” … 58

“Old Polypod” … 59

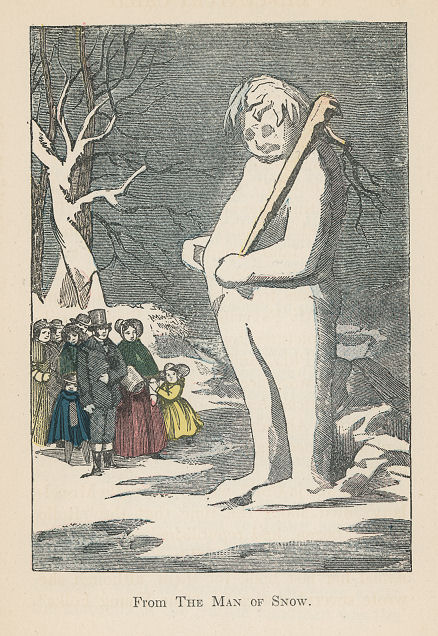

Illustration in color from “The Man of Snow,” by Harriet Myrtle … Facing 60

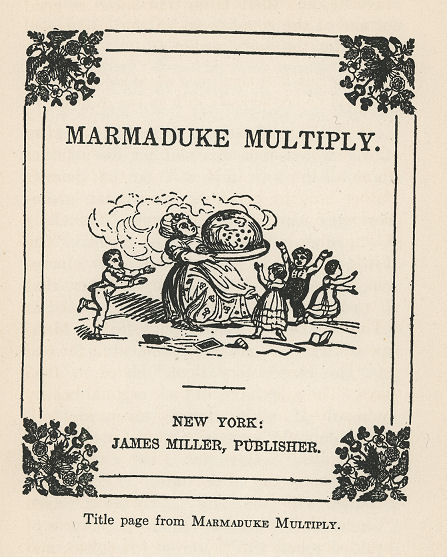

Title-page from “Marmaduke Multiply.” James Miller, New York … 63

"Twice 1 are 2.” Another page from “Marmaduke Multiply.” James Miller, New York … 67

Chiron and Jason from “Tanglewood Tales,” by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Ticknor & Fields, Boston, 1852 … 71

A page from “The Story of Little Kate, For a Good Girl.” Philip J. Cozans, New York … 75

Illustration in color from “Prince Dorus,” by Charles Lamb. M. J. Godwin, London, 1811 … Facing 80

A page from “Rhymes for the Nursery.” G. W. Cottrell, Boston, 1837 … 83

Illustration from “The History of Johnny Gilpin.” Daniel S. Durrie, Albany … 87

Illustration from “The History of Goody Two Shoes.” E. H. Pease & Co., Albany, 1852 … 91

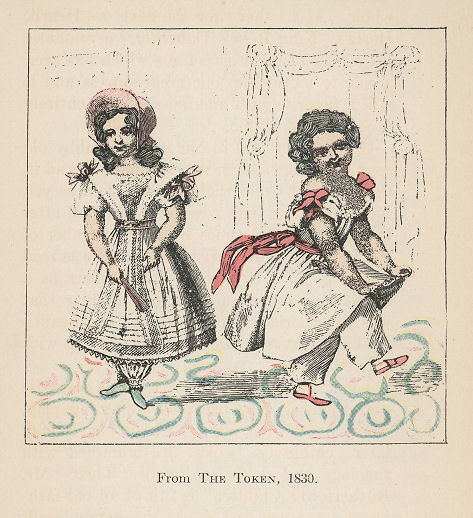

Illustration in color from “The Token,” edited by S. G. Goodrich. Carter & Hendee, Boston, 1830 … Facing 94

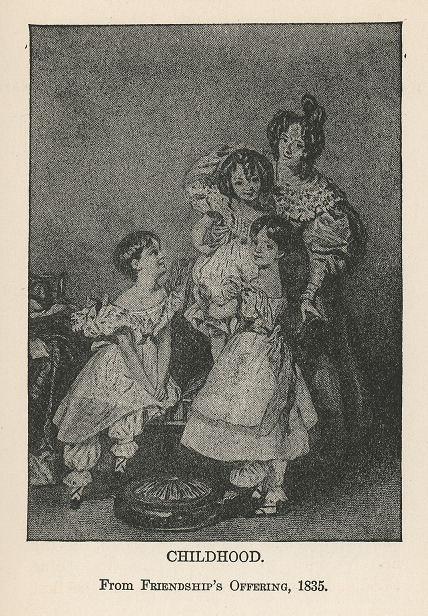

Childhood. Illustration from “Friendship’s Offering and Winter’s Wreath.” William Jackson, New York, 1835 … 97

-----

p. xi

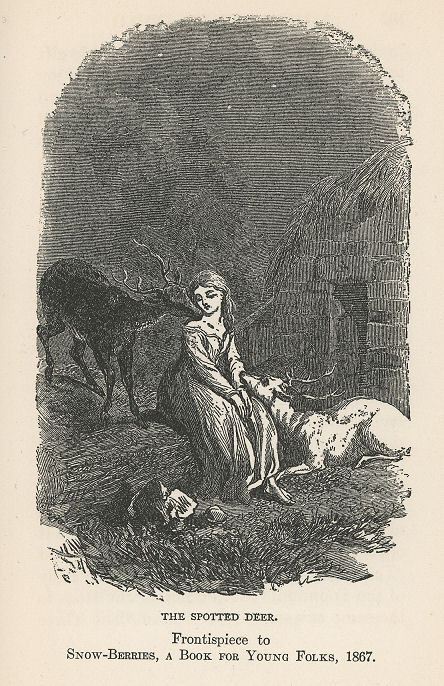

The Spotted Deer. Frontispiece to “Snowberries,” by Alice Cary. Ticknor & Fields, Boston, 1867 … 103

Decoration from “Grandmamma’s Book of Rhymes for the Nursery.” William Crosby & Co., Boston, 1841 … 107

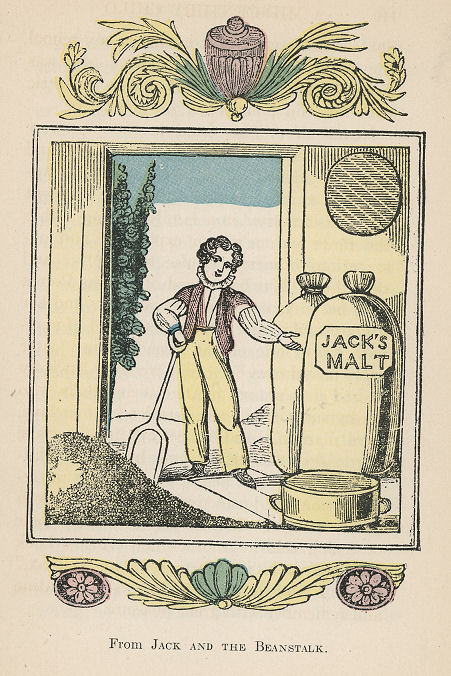

Illustration in color from “Jack and the Beanstalk.” … Facing 110

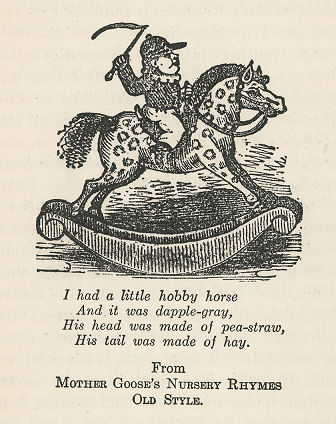

“I had a little hobbyhorse.” From “Mother Goose’s Nursery Rhymes,” Old Style. McLoughlin Bros., New York … 115

“Ride away, ride away.” From “Mother Goose’s Nursery Rhymes,” Old Style. McLoughlin Bros., New York … 120

Illustrations from “Peter Piper’s Practical Principles.” Facsimile edition, Grant Richards, London, 1902:

Andrew Airpump … 123

Davy Dolldrum … 123 [sic]

Jumping Jacky … 123 [sic]

X, Y, Z … 123 [sic]

-----

[blank page]

-----

[p. 1]

THE CHILD HERSELF

-----

[p. 2]

Title page decoration from Lilliput Levee, 1864.

-----

p. 3

AND

HER BOOKS

PART I

THE CHILD HERSELF

Not every little girl lives in the house with a great-grandmother, a lively little old lady who played a very good game of whist, a grandmother, two aunts and an uncle, besides her father and mother. The great-grandmother tried to teach me how to knit when I was four years old, but the only result was a distaste for knitting which I have never been able to overcome. Perhaps it would have grown easier if she had continued the lessons, but she went to live with another daughter when we moved a few miles farther out of town. A great-aunt of ours lived on the other side of Boston, and it was an event to go to her house with our grandmother or one of our

-----

p. 4

aunts for a day’s visit in the summer vacation, changing from steam-car to horse-car, waiting at Charlestown bridge for the schooners to go through the draw, seeing the bright red lobsters in the little shops at each end of the bridge, and Bunker Hill monument towering up before us. It was nearly noon when we rang the door-bell and were greeted by her pleasant-faced maid, Joanna, who usually told us that our aunt was out but would be in soon, and had left word for us to make ourselves at home. In a few minutes Joanna would come in with a large pitcher of lemonade and a loaf of sponge-cake, such as no one but aunt could make. She had a kitchen of her own with a Brussels carpet and her own special kitchen utensils, never touched by anyone else. After we had had all the sponge-cake and lemonade we could hold, there were always two books on the parlor table to look at, one of them “The Homes of American Authors,” the other a large edition of “Lalla Rookh,” which had one fo the most fiendish pictures I ever saw, illustrating “The Veiled Prophet of Khorassan.” By the time the thrills attendant on this had subsided our aunt would come home, delighted to see us.

-----

p. 5

It was not very long before early dinner was ready, and we were fed with delicious thick steak and water-melon, with the addition of green peas for the elders. After dinner we walked on the graveled garden paths, which have always recalled to me the lines in “O Mother dear, Jerusalem,”

Thy gardens and thy goodly walks

Continually are green.

There was hardly time for a visit to a little cousin across the street when we were called in to tea, and after that came leave-takings and the crown of the whole day to the two little sisters who were in the party, permission to go to the closed piano in the back parlor and choose whatever gift they liked best from those that covered the top. One was a small sugar bonnet, I remember, that lasted for years, and there were picture-books and games and all the things that children like best. I was too old for them, but one day when aunt gave me a dollar at parting I spent it on my way home for a copy of “Idylls of the King,” which I have yet.

I was born in the old town of Roxbury, now a ward of Boston. The only thing that I

-----

p. 6

know about my birthplace is that there was a pond with goldfish in the garden. The house was burned before I was old enough to be taken to see it. We left it before I was two years old and went to Jamaica Plains, two or three miles farther out. There we stayed for five years, and I remember the house and garden very well. The garden was large enough for old-fashioned flowers, coreopsis, mourning bride, hollyhocks, portulaca, larkspur, monkshood and the rest, the names of which I learned as a matter of course and have never forgotten.

Then my father bought from Francis George Shaw, the father of Robert Gould Shaw, five acres of land in West Roxbury. There he liked to work on summer mornings and holidays. He had a blue smock, such as farmers used to wear, that covered him from head to foot and kept him from soiling his clothes. He planted trees of which there are one hundred and twenty left. One tree, an elm, was too large to move and remains where it was when the land was bought. A large, flowered magnolia was a great ornament to the garden which was planted after we moved to the new house. But an ever-

-----

p. 7

green, over which a wistaria had run, was blown down by a severe gale and in its fall injured the magnolia seriously. The vegetable garden gave all that we could use and some for friends. In the pastures anemones bloomed on May Day, and within a short distance were hepaticas, not in large numbers but enough to give a few precious blossoms to flower lovers, who knew where to find them. An uncle of ours and one of his friends used to look for them every year, not together—for they lived several miles apart—but the first of the two to find the buds open always left his card there for the other. For years the pasture was full of fringed gentians in September and early October; but the winged seeds have a way of flying off to no one knows where, and one year there was not a plant to be seen. The next year, about a mile away, I happened to find a flourishing colony that probably sprang from the vagrant seeds, the descendants of which never came back.

Beyond this pasture were woods with Indian pipe, wild indigo, partridge berries and flowers whose names we did not know. A little farther on was what we called The Lake

-----

p. 8

of the Woods. It was dry in summer, but full in spring and fall, and we always connected it with Grimm’s “Iron Man,” half expecting to see him come out of the water. In the swamp opposite there was a pond and a spring that flowed all winter and did not freeze solid, as was proved by a goldfish that came out of it in fine condition several months after he was put in. In the pasture our cow grazed. Her name was Jessie, which dates her to 1858 when Frémont was candidate for President. I was induced to learn to milk by the gift of a small, orange pail, but my only effort showed that “Cushy cow, bonny” would not “let down her milk” for me and that the consequence would be a smaller yield even to grown-ups and experience handlers of kine, therefore I was not invited to milk again.

There were few entertainments for children in country villages at that time. One evening Signor Blitz with his wonderful taking dog, Bobby, and a troupe of trained canaries filled the by-no-means large Hall, and delighted every child there. After that, other “magicians” came; but not one of them was as attractive as dear Signor Blitz.

-----

[p. 9]

THE PET.

Frontispiece from The Fairy Gift.

-----

[p. 10 blank]

-----

p. 11

Children’s parties were simple and early, from two o’clock until six on Saturdays, in Sunday clothes, with games like “Pillow,” “Post Office,” “Open the Gate as High as the Sky,” “Uncle Johnny’s Very Sick,” “Hunt the Squirrel through the Wood,” “I’ve Lost Him, I’ve Found Him,” which can all be played in a room without boisterous running about. Out-of-door picnics for schools were unheard of. Kissing games, which at that time were a matter of course at picnics for grown-up young folks, soon fell into disuse except in the back country.

In the summer there were two days that we longed for, and remembered with great pleasure. One was a drive to Sharon, about fifteen miles and back, to visit a great-uncle and some cousins who lived in the old farmhouse which had belonged to the family for a hundred years or more. It was a low, unpainted house with a gambrel roof, lilacs in the front yard, and a cheese room where we could follow the making from the curd to the finished product set away to ripen. Near the house was a pond where turtles sat sunning themselves on logs, and a pleasant walk through the woods around the edge of the

-----

p. 12

pond, to where lady-slippers and checker-berries grew. On the way to Sharon we looked for the school children who stopped playing at recess to bow and curtsy to the strangers driving by, a mark of good manners which has unfortunately fallen into disuse in this country. It was sometimes dark before we were at home again, and I remember my first sight of a large number of fireflies dancing in a meadow, and recalled Drake’s:

Through their clustering branches dark

Glimmers and dies the fire-fly’s spark—

Like starry twinkles that momently break

Through the rifts of the gathering tempest’s rack.

The other summer holiday was in Milton, on the eastern side of Blue Hill, where there was another farmhouse near a pond. Huckleberries grew there for anyone to pick, and we carried home all that we could use. Before we said good-by we had supper at a long table, flapjacks nearly as large as dinner plates with cider apple-sauce, which we never saw anywhere else. The old lady whose house we were in was a relation of our “Uncle John,” who was not related to us except by the mar-

-----

p. 13

riage of his brother to our aunt. He used to tell us of spending a winter there. One morning the fire was out, and he had to go half a mile to get a burning log to rekindle it. It was before matches were in general use.

We learned to watch for shadbush in bloom where the shad came into the rivers, and once, without looking for them, I found calopogon and pogonia growing in a meadow. At another time by the banks of the Charles River I walked unexpectedly close to a tall bush of pink-purple flowers that I somehow knew as Emerson’s “fresh rhodora in the woods.” It was the only one I ever saw in Massachusetts, but in Connecticut it is not at all uncommon. A small plant with blossoms of the same color, the fringed polygala, grew near a brook in another woodsy place, to be looked for in May. The Fourth of July was the time to expect the white azalea and water lilies that grew near the river. Every month had its own wild flowers, up to November, when witch-hazel bloomed “like a gleam of pale sunshine”—as one nature-lover describes it.

Apple and pear time in the fall was always

-----

p. 14

welcomed. We knew the names of the pears, Louise Bone, Seckel, Beurre d’Anjou, Clapp’s Favorite, Beurre Bose, Flemish Beauty and the rest that our father had planted. Some of the apple trees, Red Astrachan, Snow, Baldwin, Russet, Greening, were on the land when we bought it, and we helped in the picking and the packing in barrels.

The County Agricultural Society had a fair every September in a large building and grounds in Dedham. We all went, as a matter of course, and visited the spading contests, where a skillful Irishman, Dennis Doody by name, always came out at the head. Then we visited the horses and cattle, and ended in the hall where the vegetables, fruit, patchwork quilts and fancy-work were on exhibition. In the afternoon there were horse races and, once certainly, a baseball game. I went to see it from school without luncheon, and distinguished myself by fainting in the hot sun.

Of children of my own age I knew very little. One or two in the neighborhood used to come to play with me, and a cousin lived not far away. But, not going to school, I did not learn out-of-door games and had more

-----

p. 15

spare time than if I had been in the school-room morning and afternoon. There were no kindergartens then on this side of the

From Mother Goose’s Nursery Rhymes Old Style.

Atlantic. If there had been, I should have known many things that I have never learned.

It was in the early fifties that my mother taught me to read and spell. I do not re-

-----

p. 16

member the process, but I have no knowledge of a time when the words in an ordinary printed book and the marriages, deaths and accidents in the Boston Evening Transcript were beyond my powers of pronouncing and understanding. “My First School Book” was the means of an easy and pleasant acquaintance with print. My copy disappeared long ago; but in a collection of school books within my reach is one much fresher and less used, from which I am able to renew my acquaintance with “The Disobedient Rabbit” and the two boys, one selfish and one generous, who had ninepence each to spend on Fourth of July. One ate up his very soon, but the other one proved his altruistic character by spending half of his wealth for an orange to give to a sick friend. “Emerson’s First Part,” a simple little arithmetic, had pictures to beguile young mathematicians along the difficult paths of addition, subtraction, multiplication and division, with sometimes a short story like this: “When Nathaniel was sick, one of his schoolmates brought him four grapes, but his physician said that he must eat only one at a time. How many times could he eat one before they were all gone?” The

-----

p. 17

little book ended with the multiplication table up to twelve times twelve. I never saw afterward an arithmetic for school use made enticing with pictures.

There must have been picture books given me in my early days that went the way of most paper-covered books for children. I remember dimly one about a wood-cutter, but it was not Red Riding Hood. The pictures of that date were usually very crude, colored by hand with a generous bestowal of vermilion, Prussian blue, gamboge and crimson lake that overflowed the edges of the children’s garments. A little earlier the colors were put on by boys and girls, each of whom was responsible for only one tint before passing on a picture to the next in order.

The school where my brother and I went was first in a large, sunny room in an old-fashioned house where an old lady, known as Aunt Electa, was kindness itself to the children, especially if they had fallen or had any of the various pains and aches that children have. After a year or two the school was moved to a small building farther away from the village street, and remained there until the teacher was married and went to

-----

p. 18

Europe for a year before going to live in Boston.

There was a little girl in the class above me who was a bookworm and had the run of two libraries, one a minister’s, the other the property of a leading Boston publisher. We came together like “halves of one dissevered world” and what one had not read the other had, from Miss Yonge’s “Daisy Chain” to Edgar Allan Poe.

One day a pleasant white-haired man came to our house to sell some books he had written. His name was Warren Burton, and he was well known as a teacher until he retired. One of the books, “The District School as it Was,” was a favorite of mine and I lived over the life of the boys and girls in the little red schoolhouse, from three years old to the nearly grown-up pupils of the winter months, the teachers, from dear Mary Smith to the pompous or ineffective college students, and the champion speller who understood an order from the master to “go and spell Jonas”—who was splitting wood—to mean that he was to give him all the hard words in the spelling book and report on those he missed. An “exhibition” was a festive occasion to them,

-----

p. 19

with “pieces” spoken and, once in a while, a dialogue or a scene from a play enacted on a stage curtained with checked blankets and lighted by candles or oil lamps.

This country school was of the late twenties or early thirties. Some improvements had been made in schoolhouses before 1850, but they had none of the luxuries of to-day. There were no swimming pools, gymnasiums, folk-dances, library books, luncheon counters, pianos, fire-drills, sewing, graduation presents, talks about books or pictures, celebrations of Christmas or other holidays, or manual training. Children had less “homework” than they do now, and life was not as hurried. Country boys and girls had chores to do at home that kept them busy a part of out-of-school hours, and made them grow up under a sense of responsibility. Girls had washing dishes, sweeping, dusting and keeping rooms in order; the boys shoveling snow, feeding horses, cows and poultry, and doing errands. In most families the girls did a “stint” of sewing every day, and some of them cross-stitched the alphabet large and small, the figures up to ten, and their name and age in bright-colored wools on canvas, the elaborate and dismal samplers

-----

p. 20

of years before having gone out of fashion. Their place was taken by slippers in cross-stitch and crocheted bags of twine for carrying luncheons and other school properties, in addition to a book or two. Sewing was not taught in country schools, and cooking was an unheard-of part of the curriculum. If a girl liked to cook there were opportunities for her in the home kitchen.

One of my earliest remembrances is of sitting in front of a soft-coal fire and hearing “Flow gently, sweet Afton” sung. After I had learned to read, the singer, and aunt who died before I was six, must have shown me the song in her little fine-print, gilt-edged Burns with a black and gold cover, for I should hardly have found it for myself. There were a great many words in the book that I had never seen, but a glossary at the end told me what they meant and I read some of the poems over and over, till before I or anyone else know what I was doing I was able to read Lowland Scotch easily, and never had to stumble over it in later years.

I was about seven when I was taken to hear a trained orchestra and Camilla Urso, then a girl of fourteen or so, with braids of

-----

[p. 21]

An old title page.

[Text:]

Prince Dorus

BY

Charles Lamb

WITH NINE COLOURED ILLUSTRATIONS

IN FACSIMILE

INTRODUCTION BY

ANDREW W. TUER, F. S. A. [picture of naked child]

[decoration]

1890-1.

LONDON:

The Leadenhall Press, E. C.

———

Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., LTD:

New York: Scribner & Welford, 743 & 745, Broadway.

-----

[p. 22 blank]

-----

p. 23

hair down her back, who played the violin wonderfully. It was something to remember, everyone said. Applause, which I had never heard before, frightened me at first, until I understood what it was. There were no children’s concerts in those days, and I did not hear any great music again for several years.

The first play that I remember seeing was “Cinderella,” though my impressions of it are fragmentary, chiefly of the fairies in spangled white and of Pedro’s funny tricks. The next play was “The Midsummer Night’s Dream,” which I did not read until after seeing it.

In those days anyone who was on Boston Common on May Day could see groups of girls in white muslin, usually with a boy as King of the May. There must have been many colds and attacks of pneumonia for the rest of the month. The first May Day party that I ever went to was in the large parlor of a neighbor’s house. It was given for the hostess’s niece who had been ill the winter before, and had been promised a May party by her aunt if she would get well in time for it. A tall Maypole stood in the middle of the room, and every girl but one had a wreath of arbutus—she was a little older

-----

p. 24

than the others and wore a wreath of pansies. I think that the boys had wreaths, but am not quite sure. I kept mine quite dry for several years. The party was over at sunset, and everyone went home happy. May parties were not uncommon, though a Massachusetts May is, as Lowell said, “more like mayn’t.” The schools of to-day have found it wiser to crown their May Queens later in the month.

At one of the simple afternoon parties a sea captain, whose home was in the neighborhood, and who had just landed from a long voyage, came in with something new and strange in his hand—a stereoscope and a few views at which we were all invited to look. The only one that I remember distinctly is Notre Dame. It was not long before we had a stereoscope of our own, with views of Tintern Abbey and other delightful places that were soon as familiar as if we had really seen them.

In the early fifties Christmas trees were not common. Stockings were hung on Christmas Eve and filled with small presents, including candy animals; but the family celebration was later in the day. The first Christmas tree

-----

[p. 25]

CHRISTMAS EVE

From Youth’s Keepsake, 1841.

-----

[p. 26 blank]

-----

p. 27

that any of us ever saw was a hat-tree covered with pine branches and hung with toys, books and whatever children would like best. Santa Claus came with it to distribute the gifts, though his call was short on account of the many homes that he had to visit. I remember that there were waiting for me a doll’s iron bedstead, with beautifully made sheets and blankets, a wax doll beautifully dressed, a gold pencil and a silver fruit-knife which I have to this day.

One year, when I was twelve or thirteen, a family in the neighborhood persuaded a dancing teacher to open a class in the hall which was our only place for lectures, concerts or dances. There were about a dozen girls to every boy. The teacher was a woman of mature years with carefully woven hair on each side of her face, a black silk gown, and very neat feet in black silk stockings and slippers. The Varsovienne, the Polka, Redowa and other dances of the period were taught us as well as the Lancers, other “square cotillions” and some of the old-fashioned country dances. At the end of the quarter there was an exhibition in the evening when the girls all wore their prettiest dresses. Mine

-----

p. 28

was a low-necked, sky-blue barége with a tucked skirt, a sash of the same color, and hot-house flowers at the back of my head.

Adelina Patti was seventeen, I thirteen, when I listened for the first time to an opera, “Don Giovanni,” sung by the finest voice I have ever heard. Patti was lovely to look upon, and one of the papers said that when she danced with the tenor it was like an elephant turning round a gazelle. I never wished to hear her after her voice broke, and I have always remembered her as I heard her that Saturday afternoon in the Boston Theatre.

In the middle of the century the Warren Street Chapel was much like the modern settlement. The Reverend Charles Francis Barnard made it a church for children, and gave them opportunities of seeing good pictures and statues. Because there were dancing classes in the chapel, he was known as “the dancing parson.” He formed the idea of engaging the Music Hall for May Day with an orchestra to play, and letting the children dance as much as they pleased. We used to go with a group of other girls, sometimes under the care of one mother, again with two

-----

GRANDFATHERS [sic] WIG

From Peter Parley’s Tales.

-----

p. 29

or three. There were tableaux in a small hall on a lower floor, flowers and ice cream for sale, and it was altogether a very pleasant day to remember. A remembrance of the Music Hall even earlier is of going to one of the horticultural exhibitions when I could not have been more than three or four years old. One of the party opened by mistake the door of a room where a committee of white-haired gentlemen was deciding on prizes for grapes and pears. I began to cry when no one offered me even a taste of one, and the door was hastily shut behind us.

Schoolrooms of those days were bare and uninviting compared with their modern successors. Our high school was in a hall the use of which for town meetings gave us three days’ holidays, “one to make ready,” the second for the meeting and the third for cleaning. On a raised platform on one side was a large glass case of apparatus used to illustrate what is now called physics. There was not a photograph of any famous building, picture or statue in the room. Equipment was of the simplest and most meagre, but the teaching was so thorough that I have never forgotten Latin or French irregular verbs, and

-----

p. 30

can read the two languages at sight as well as I ever could.

My high-school diploma was given me, and then, because I was younger than the other graduates, and colleges for girls were in their infancy, it was a puzzle what to do with me next. The Girls’ High and Normal School, as it was called, in Boston was highly recommended. I passed the examination on one of the rainiest days of my life, and was admitted. It was not easy to adjust myself to the conditions there, in a class of sixty or seventy girls who had had public-school training from the beginning; but I floundered along somehow and kept my head above water, although my marks were not high. The normal training was for the most part obtained by the Squeers method of substituting in the schools where a teacher was ill or absent for any reason, and we had no lectures on pedagogy.

Before long I began to make friends with a few girls who were lovers of literature, and they introduced me to “Water Babies,” “Marjorie Fleming” and other books that have lived for more than half a century. The class had free discussion in the English literature

-----

p. 31

hours, and gained the habit of talking easily and to the point, though some views were original—to say the least. When we were reading Gray’s “Elegy” one of the girls insisted that “the little tyrant of the fields” was some small animal, like a weasel or a fox.

Another habit, unusual in schools of that date, was connected with our study of history. We had “date-books” in which we wrote from dictation brief histories of reigns, to be learned for the next lesson, in addition to a full account of an earlier reign from books at home, in the public library, the good school library or anywhere else. I read French more easily than most of the girls, and quite as often took the history of a reign from a book of that language on the school shelves as from histories in English.

The “Elegy” followed Gray’s “Bard” and preceded “Hamlet,” which led to many long discussions over sentences and phrases not easy to understand. We had not much practice in writing English. I cannot remember writing more than one theme, or “composition,” as it was called in those days. A list of subjects was read aloud and the girls chose what they liked best or thought easiest, with-

-----

p. 32

out consulting a teacher. When the teacher read the essays she went over her corrections or suggestions with every girl; but there was not practice in the use of words as there is now. The girls learned some things thoroughly, but could go through a four years’ course without any real training in the English that is now a favorite elective in college.

The school year ended and most of the class began teaching in the graded schools. About a dozen stayed for the advanced year of languages, psychology or mental philosophy as it was called then. There were one or two other studies which I have forgotten, except chemistry, which nearly blew me up one day. The writing habit was encouraged by what were called “special exercises,” when after weeks of hard work had brought forth a paper on some literary or scientific subject, the author or compiler was invited to read it in the school hall to an admiring audience from all the classes.

The school had invitations to hear and see the favorite musicians of the time, one of whom—Teresa Carreño—was a child-wonder from South America who played remarkably on a grand piano in Music Hall. The schools

-----

[p. 33]

LONG MEASURE.

A page from Dame Wonders’ The Table Book.

-----

[p. 34 blank]

-----

p. 35

gave a concert in the same hall for the officers of a Russian warship that was anchored at a Boston dock for a short time. In return they invited the schools to visit the ship on a specified day. The school principals agreed that a general invitation would bring too great a crowd, and that it would be better to limit the guests to the graduating classes in the high schools. It was a cloudless day in late June or early July, for the summer vacation did not begin until after the middle of the month. The ship was spotless, and the officers were in equally immaculate uniforms. There were flowers everywhere, and later a delicious luncheon was served. Some of the officers spoke excellent English, and those who did not made themselves understood by gestures or French phrases. The ship’s band played for dancing on deck. It was the first time that the girls had met foreign naval officers and they never forgot them. A member of one of the graduating classes and the most attractive girl in it was escorted home by her partner in the dance, and was an object of envy. Altogether, it was a delightful day and a pleasant ending to our school life.

Our schoolhouse had once been a medical

-----

p. 36

college—of some notoriety from the murder of Dr. Parkman by Dr. Webster and the discovery of his remains in the furnace by the janitor, who showed in evidence a set of false teeth identified by the dentist who made them. The basement and cellar were ghastly enough to be the scene of any crime. The house was in Mason Street, just around the corner from West Street and the stately houses of Colonnade Row, at the window of one of which a white-haired gentleman used to sit, the youngest son of Paul Revere and the father of two sons killed in the Civil War.

My grown-up library began with the first edition of Hawthorne’s “Marble Faun” and was soon increased by Longfellow’s “Golden Legend,” a blue and gold Tennyson and Jean Paul’s “Titan” in two thick volumes, which I have never found interesting. Palgrave’s “Golden Treasury” is a book that I bought at about the same time, and I never look at it without a feeling of thankfulness that I own it. Pope’s Homer and Wright’s Dante have Flaxman’s outlines to add to their interest, and I was familiar with the pictures in both before my high-school days. I had

-----

p. 37

had very little public-school training and was at a disadvantage in much of the new work, but an acquaintance with the Greek and Roman gods and goddesses and the Siege of Troy besides the habit of looking up subjects in the “Encyclopædia Britannica” kept me from absolute ignorance. I knew something

LITTLE BOY AND HOOP.

From Grandmamma’s Book of Rhymes for the Nursery, 1841.

of great artists and their paintings. Pictures and statues with stories always appealed to me—such as Crawford’s Orpheus, Virgil and Dante meeting the Latin poets and the Scheffer Dante and Beatrice. I knew the Flaxman outlines in the Wright translation of Dante, and also in Pope’s Homer, and the

-----

p. 38

floating figures of Paolo and Francesca on the library wall of a Dante scholar.

One-fourth of the boys in the High School, taken in alphabetical order, “spoke a piece” every Friday. The girls, although they mounted the platform to read what were then called “compositions,” were not expected to repeat in public the poetry that they learned, but were permitted to say it at the noon hour or at other odd times to a teacher in the privacy of a class-room. In four years a girl could commit to memory and make her own forty poems she had herself selected, and of any length she pleased. In this way I learned many lines of Longfellow, Tennyson and Scott and some poems of Milton, Bryant and Whittier. One Christmas I was given a copy of “L’Allegro,” illustrated and without notes, and I learned it by heart with the enjoyment which a girl who reads it for the first time in “College English” requirements where Cerberus, the Styx, the Graces, May Day, the skylark, Queen Mab and Robin Goodfellow are supposedly unknown and carefully explained, can never feel.

In West Roxbury there had been a small library in a room leading out of “Betsy’s”

-----

p. 39

country store, where she sold a varied assortment of goods from molasses to calico. The library had been closed for many years, but at the beginning of my last year at school it was moved to a room not much larger, that was used, when necessary, for a dressing room at dances in the hall where it adjoined. This library was remarkably well chosen and had received many gifts from Theodore Parker during his ministry in the old white church not far away. It was kept alive by annual dollar subscriptions, and cared for by an old gentleman and his wife who were “uncle” and “aunty” to all the children in the neighborhood. They bought the books, prepared them for circulation, made the fires in the stove all through the winter months, repaired loose leaves and bindings and were at their posts every Monday for fifty weeks in the year. They gave their services freely, but after a while the circulation increased and an assistant was employed at twenty-five dollars a year, afterwards increased to fifty. Everyone in town regardless of church or political affiliations would help the library, and though the actual assets were not large judged by city standards, they meant a great deal to us.

-----

p. 40

Various entertainments were given for it, fairs, suppers, a Dickens party, an exhibition of antiques, tableaux with negro spirituals sung between, led by a woman who had given years of service in the South Sea islands. When the librarian and his wife were on vacation it fell to me, as secretary of the Library Association, to charge and discharge the books in a ledger under the names of the readers. The pleasure of knowing the library well enough to find books easily was increased by the treasures on the shelves, unnoticed by most of the readers, Ben Jonson, Leigh Hunt, George Sand’s “Consuelo” in the translation by Francis George Shaw and first published in the Brook Farm paper, the Harbinger, and “German Romance,” with the eerie “Golden Jar,” some of Tieck’s fairy tales and Jean Paul’s “Quintus Fixlein.” An English neighbor who went home for a visit brought back a collection of three-volume novels for the library. They were received with some doubt and looked over carefully before they were admitted to the shelves, but I never heard any objections made to them, though

-----

[p. 41]

From The Fairy Gift.

[Text:]

S Simon Sobersides, serious and soft,

T Timothy Touchstone, tomboy and torch,

U Uniform, Union, and Unicorn trot,

V very vexatious his letters forgot.

-----

[p. 42 blank]

-----

p. 43

they were probably the work of second or third class authors. Some of the families in the town finally decided that the library would be more used in a more central position, and it was moved into a room a little larger than its former home, and made free to all the inhabitants of that part of the town—men, women and children.

There was a reading club in our village after the free library opened, and once or twice in the winter the members used to impersonate the characters from some favorite author. Once we had a Mother Goose party, when one lady made a great success as:

My mother’s maid,

She stole oranges, I’m afraid,

Some in her pocket and some in her sleeve;

She stole oranges, I do believe.

Wherever she was she dropped an orange. We had a great stuffed goose, though I cannot remember where we borrowed it. I was so worn out with reading notes of regret that I did not care what I stood for, and with a sad countenance and a dismal gown I answered the doorbell as “The maiden all forlorn,” which made some of the guests think

-----

p. 44

that something serious had happened to one of the family.

My twenty-first birthday was an unusual day for October, almost as warm as midsummer with nasturtiums untouched by frost, and cut in long trails to decorate the house for a Dickens party. My father, as Mr. Wardle, received the guests the first part of the evening, and later appeared as Alfred Jingle. I had asked not to have it entirely a young party and, on that account, the characters were played with much more spirit than if the parts had been taken by boys and girls. It made no difference whether they had ever met before or not. Captain Cuttle and Jack Bunsby brought down the house by dancing a “fore and after.” Sairey Gamp did not know that Betsey Prig would be there but when they saw each other their only regret was that Mrs. Harris had not been invited. Dolly Varden and her mother were in evidence, Dolly with her hair elaborately dressed by a kind neighbor. Betsey Trotwood was there and the faithful Janet, Sam Weller and Bob Sawyer, Lizzie Hexam and the Doll’s Dressmaker, Mrs. Jarley and Little Nell. I

-----

p. 45

wish that we had kept a list of the characters, for some of them have entirely gone from my memory.

The next morning was dark and cold and rainy. The nasturtiums were all frost-bitten in the night. But the fun and unexpectedness of the party remained with all who were present.

-----

[p. 46 blank]

-----

[p. 47]

HER BOOK

-----

[p. 48]

From Prince Dorus, 1811.

-----

p. 49

HER BOOKS

Looking back into the early fifties, I can see as plainly as any of the faces of family or friends the big, unwieldy, two-volume Froissart in a faded purplish binding with a gilt knight on horseback on the cover, and pictures of ladies in litters and processions of knights and soldiers that I loved to look at, and the fat one-volume edition of Gibbon in figure much like the author. Both books must have been too tall for the bookcase shelves, because they were on the table between the front windows. In the room where they lived I was discovered one Sunday afternoon reading Godey’s Lady’s Book which, although extremely mild and harmless, was thought in those days a little grown-up for a person of four and a half. The next day I was taken into town and made the proud owner of a copy of Jacob Abbott’s “Lucy’s

-----

p. 50

Conversations,” my first bound book, which I have to this day, with my name and the date in it. It is in this book that Lucy has croup in the night and the next morning is given a powder in jelly and a roasted apple that was cooked by hanging it in front of the fire from a string held by a flatiron on the mantelpiece.

The other Lucy books followed in due time, at intervals of a few months. Was there ever a more delightful journey than that which Lucy was invited to make to the seashore with her friend Marielle and Marielle’s mother, the mysterious Lady Jane who “came form some foreign country”? How grand it was for the little girls to travel in a carriage, to have tea by themselves in Lady Jane’s sisters library, waited on by a black serving man, and to look at drawers of curiosities, shells and minerals and a picture in mosaic of a burning mountain, by way of entertainment! “Lucy in the Mountains” is not nearly as impressive or awe-inspiring; but the stay at the General’s and his monthly inspection of everything in the house and farm buildings, ending with a round cake for every one of the children, lingers in my memory together with the “beautiful little apple pie” in “Lucy’s

-----

p. 51

Stories” and other food described with the detail which Jacob Abbott knew children love. An American family as simple and happy was described in “Clara’s Amusements” by Mrs. Anna Bache of Philadelphia, a descendant of Benjamin Franklin, who in her preface says that she has seen the plan of parents interesting themselves in their children’s recreations “acted out with success in a family of small means and simple habits.” The children played Robinson Crusoe. Their father and mother told them about the French Revolution, showed them pictures of Robin Hood and King Alfred and taught them how to make scrapbooks, play games and guess riddles. They learned, too, from their mother’s example to be good neighbors and help her cook for a poor, sick woman, and to make her more comfortable. In all this there was no self-righteousness, but a perfectly natural and wholesome spirit.

It could not have been long after this that Lane’s three-volume “Arabian Nights,” with Harvey’s illustrations, came to a shelf in the grown-up bookcase, not too high for small hands to reach. I did not read “Aladdin” or “The Forty Thieves” for several years, be-

-----

p. 52

cause they were not in Lane’s edition, but long before I had ever seen or heard of them Sinbad the Sailor, the Flying Horse, Bedreddin Hassan, one-eyed calenders, dervishes, afrites, genii, gazelles and ghouls were as well known to me as the Mother Goose people or Lucy and her family.

I have now two books that were given me for Christmas just after I was six years old. They have never lost their charm. One is “Gockel and Scratchfoot, or The History of Two Little Chickens” from the German of G. Sus, published in a square octavo by Willis P. Hazard of Philadelphia, with full-page lithographs very well drawn and hand colored—the miller’s wife feeding her poultry, the visit of Scratchfoot to her aunt, the duck, and the triumphant return of the two lost chickens in a flower-decked basket carried by Henry and Christina, the brother and sister who had found them in the wood. Within a few years I have seen in a German bookseller’s catalogue a picture of this author, Gustav Sus, with his two children. He was of the Düsseldorf School, and an artist of some reputation as well as a story-teller and writer.

The other book is “The Man of Snow” by

-----

From Gockel and Scratchfoot, or, The History of Two Little Chickens.

-----

p. 53

Harriet Myrtle (Mrs. Hugh Miller, wife of the geologist), one of a series of three, telling the simple, happy life of a family, father, mother and little girl, who go from London to live in a cottage in the country. “The Man of Snow” is the record of a joyous Christmas time, when the mother tells little Mary and her two boy cousins about the funny things that happened to a snow man when she was a child.

Many of the picture books of the fifties were published in Albany by Sprague or by Fisk and Little, hand colored or rather hand daubed, and in pasteboard covers. The best of them all was “The Alderman’s Feast” because it told so much about London. The city’s name is not mentioned in the book, but somehow I knew where to find Bow Church and the “yeoman so stout and tall, in scarlet and gold,” and I looked forward to the time when I should really see them. With the Aldermen and Dick Whittington for friends, what wonder that Bow Church was as familiar a building as the Boston State House? Besides, its bells were ringing in “Oranges and Lemons” in our Mother Goose, of which there were two editions that we learned by heart.

-----

p. 54

One was a reprint of the little square “only pure edition” first issued by Munroe and Francis in 1833 with wood cuts, many of them English, some with suggestions of Bewick and his school. The other was “Mother Goose in Hieroglyphics,” published by Appleton in 1849, an auction copy, more tattered and torn than the man in “The House that Jack Built.” The poem runs thus:

Robert (Barns) with (bellows) fine

(Can) you (shoe) this (horse) of mine?

Yes, good (Sir), that (I can)

As (well) as any other (man),

the words in parentheses being represented by pictures, easy to guess except, “Sir,” who is a man in full armor with shield, lance and plumed helmet. The beginning of my acquaintance with Mother Goose was from this book. The other came later. The habit of guessing the pictures had always helped me in solving puzzles in magazines, in all kinds of riddles and in digging out allusions.

I know that my mother taught me to read out of “My First School Book” because I remember the book afterward, but I have no idea how I learned the letters unless I picked

-----

[p. 55]

A page from The Only True Mother Goose Melodies, 1833.

[Text:]

There was an old woman tost up in a blanket,

Seventy times as high as the moon,

What she did there, I cannot tell you,

But in her hand she carried a broom.

Old woman, old woman, old woman, said I,

O whither, O whither, O whither so high?

To sweep the cobwebs from the sky,

And I shall be back again by and by.

[decoration]

Shoe the horse, and shoe the mare,

But let the little colt go bare. [picture of horse]

-----

[p. 56 blank]

-----

p. 57

them up from blocks or, as one of the family did later, got them from the names blown in glass bottles.

Back as far as I can remember any books I can see an old “Æsop’s Fables,” coverless and titleless, with long s’s and old wood cuts. It was Croxall’s translation into eighteenth century English with “applications,” not “morals” attached, which sometimes were as entertaining as the fables and the cuts. It is uncertain who the illustrator was, whether Kirkall or another, but Bewick followed him closely in his cuts for “Æsop.” The pictures of the gods and goddesses of Roman mythology in the sky, with Juno attended by her peacock, or the more homely scenes like “The Stag in the Ox-Stall” or “The Nurse and the Wolf” were as interesting to me as they were to the children of two or three generations before, who had read and owned the book. There is very plain English in the Fables, and words not now heard in the polite world are freely used, but I am sure that I was never the worse for them.

Maria Edgeworth’s stories, prosaic as they seem to twentieth-century schoolgirls, are of a pleasant family life where mother, father

-----

p. 58

THE COCOA-MAN.

From Beechnut: A Franconia Story, 1850.

and children have the same interests. If the mother and father went to pay a visit the children went, too, and by this means met people worth knowing. The Edgeworths’ friends and family connections—the Wedgwoods, the Darwins and others—were all in advance of their time, inventors or men of science, and it is life with such families that Harry and Lucy, Frank and Rosamond Knew. They always had something to do and to

-----

p. 59

OLD POLYPOD.

From Beechnut: A Franconia Story, 1850.

think of—riddles, puzzles and nonsense. Their study of history was made real by games like “Contemporaries,” and they were taught to learn poetry and to connect it with history or science.

Jacob Abbott’s “Rollo Books” and “Franconia Stories” are full of practical good sense in dealing with children and in suggesting occupations for them. One of these occupations, letter writing, had an unexpected result

-----

p. 60

when Phonny let his imagination run away with him in describing the supposed burning of his mother’s house and barn, and the letter was mailed by mistake, bringing Beechnut home from Boston in the middle of a rainy night to find house and farm buildings in their usual condition.

The “Aimwell” series, published in the fifties, had the same ideals of family life. The children and the older folks on a Vermont farm had a family paper, learned to guess riddles and puzzles, and played memory games. It was from one of these books and also from “My Favorite Picture Book,” a collection of pictures by Birket Foster, Harrison Weir, “Phiz” and other English illustrators, that I was once able to answer a request in the American Journal of Folklore for “The Peter Piper Alphabet,” and afterward to have a pleasant meeting with the family who asked for it.

Lydia Maria Child, whose “Juvenile Miscellany” died about the time that the “Rollo Books” began, had republished many of her stories in “Flowers for Children.” In 1855 she issued her last book for them, although she wrote several stories for “Our Young Folks”

-----

From The Man of Snow.

-----

p. 61

between 1865 and 1869. Her “New Flowers for Children” has one of her most charming tales, “The Royal Rosebud,” the story of the little princess, Edward IV’s youngest daughter, whose mother in the troubled times after the king’s death, made her a nun as the safest way of disposing of her. Mrs. Child’s “Girls’ Own Book” taught me many games and riddles, English and French. Her “Frugal Housewife” was full of the industrious, thrifty New England spirit which, carried into her simple living, enabled her to give sums out of all proportion to her income to philanthropic societies.

Translations from the German were in fashion at this time. It was through German that Mary Howitt had introduced Hans Andersen to English readers about 1845. Some of her translations, by no means exact, had been published by Wiley and Putnam in a little square book with colored illustrations in 1847. It was in a gift book called “Christmas Roses” which belonged to Jenny across the street that I first read “Ole Luckoie,” “Little Ida’s Flowers” and “The Nightingale.” “Ole Luckoie” with its wonderful journeys under the umbrella of the Danish Sandman was the

-----

p. 62

favorite, and there is no translation as good of one of the couplets which the lead pencil made for the doll’s wedding:

Her skin it is made of a white kid glove,

And on her he looks with an eye of love.

It must have been two or three years after this, when it was an event for one’s father to go all the way to New York, that Jenny’s father brought her from there a fat, green-covered Andersen with the creepy “Travelling Companion,” “The Little Red Shoes,” “The Little Mermaid” and all the other stories. She had another book, too, even fatter, that I tried to find for years and at last traced as “The Child’s Own Book,” published by Munroe and Francis. An advertisement at the end of “The Boys’ Story Book” issued in 1845 says, “The tales have all their original beauty unimpaired; nothing changed except any vulgar or mproper expression unfit for the juvenile reader.” How the titles “Griselda,” “Jack and the Beanstalk,” “Peronella,” “Riquet with the Tuft,” “Fortunio,” even “Cinderella,” bring back the little pictures of beauteous ladies in short-waisted gowns, and the amateur dramatized versions of “Blue-

-----

[p. 63]

Title page from Marmaduke Multiply.

-----

[p. 64 blank]

-----

p. 65

beard” and “Fatal and Fortune” performed in the barn by some venerable persons of sixteen and eighteen before an admiring audience of fewer years! How the book recalls, too, the glorious Hall of Mirrors in “The Invisible Prince” and Bluet, the Princess’ cat, deprived of his food by the supposedly invisible Leandor in full sight of the audience, in all the beauty of his blue and silver doublet and white-plumed hat.

Grimm’s Fairy Tales, although they were published in 1853 by C. S. Francis in a very good two-volume translation with Wehnert’s illustrations, did not come into the house until nearly ten years later and stayed for only a short time, for the precious copy was sent by the owner, a younger sister, to the soldiers in the hospitals as the dearest thing she could give to her country.

Munroe and Francis were the American publishers of “Marmaduke Multiply,” who made even the multiplication table amusing and easy to learn. Is it possible to forget “Five times twelve are sixty,” illustrated by a sour-faced woman picking her steps over a threshold and saying, “This house is like a pigsty,” or “Four times eight are thirty-two,”

-----

p. 66

where a very fat, waddling person exclaims, “I once could dance as well as you,” or “Seven times eight are fifty-six,” where a boy is running away after having broken the toy cart belonging to another who, instead of running after him and giving him what he deserves, is merely standing in a wooden attitude and saying, “That fellow merits twenty kicks”?

“The Wonder Book” was on my pillow when I opened my eyes on the morning of my seventh birthday. The purple-covered “Tanglewood Tales” with Proserpine and Europa, Theseus, Jason and Circe is still mine; but the dear green “Wonder Book” with the Hammatt Billings pictures of the groups of children on Tanglewood porch, Perseus holding up the Gorgon’s head, King Midas, Pandora, the three Golden Apples, Baucis and Philemon and the Chimera vanished long years ago, and not even the Walter Crane or Maxfield Parrish editions will ever take its place.

I had read, skipping the moralizing, a little old “Robinson Crusoe” in the house, with yellow paper and small type. But I never really loved it as I loved a book that was brought me from New York about this time—“The Swiss Family Robinson”—their suggestive

-----

[p. 67]

From Marmaduke Multiply.

[Text:] Twice 1 are 2.

This book is something new.

-----

[p. 68 blank]

-----

p. 69

makeshifts and picnicky ways of living in tent, tree and cavern, their pet monkey and all the fauna and flora of the remarkable island which combined the vegetation of the tropical and the temperate zones, and where everyone could do and find just the right thing in an emergency.

Grace Greenwood (Sara Lippincott) had written “Recollections of My Childhood” and “History of My Pets” a few years before this time. The stories in the first are often sentimental, but the account of her child life in western New York is most amusing. Her monthly paper, The Little Pilgrim, published in Philadelphia, came to me through the mail, and I had the pleasure of going to the post office to get it and of reading her stories of history and travel, which made Shakespeare, Scott and Byron, the royal prisoner, James I of Scotland, Jane Beaufort and Catherine Douglas, Guy of Warwick and Sir Philip Sydney real living persons whose homes I looked forward to seeing some day.

Shakespeare was not my “daily food,” but there were two books illustrated with the steel engravings of the time that led me to him. They were in the parlor where we sat on

-----

p. 70

Sunday afternoons, and were an unfailing source of pleasure. One of them was a large edition of Mrs. Jameson’s “Characteristics of Women.” From the faces, sad like Ophelia, mirthful like Beatrice, frowning like Lady Macbeth, or merely pretty and meaningless like Perdita and Miranda, I began to read what the book had to say about them, and after a while the plays themselves. The only Shakespeare girls that I had ever seen—Helena and Hermia—were not in the “Characteristics” at all. And when I saw them in “Midsummer Night’s Dream” they were overshadowed by the clowns and the fairies. The other book, Allan Cunningham’s “Gallery of Pictures,” had some of the old Boydell prints—Reynolds’s Puck, Henry V before Honfleur, the Duke of Rutland, Kemble as Hamlet, Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn and Hero and Ursula watching for Beatrice in the pleached bower. In that, or more probably in a portfolio of prints cut from magazines, were Anne Page and Slender and Christopher Sly in the palace. These all gave me a bowing acquaintance with Shakespeare characters, though for some time, two or three years perhaps, the “Midsummer Night’s Dream” was the only

-----

[p. 71]

From Tanglewood Tales for Boys and Girls, 1852.

[Text:] Chiron and Jason p. 272.

-----

[p. 72 blank]

-----

p. 73

play that I really read. The portraits of the great actors, Kemble as Hamlet and Mrs. Siddons as the Tragic Muse, in the “Gallery of Pictures” fascinated me and made me wish to know more about them and their lives. I had not been in a real theater more than three or four times, but I loved the stage and anything about actors, always reading over and over the advertisements of plays at the theaters in Boston, knowing the names and who acted in them. The first life of anyone that I ever read, except perhaps Abbott’s “Josephine,” “Madame Roland” and “Marie Antoinette,” was a book that has never lost its charm—Mrs. Mowatt’s “Autobiography of an Actress.” I was interested in her life in the old French château, the plays acted by the large family of children there, and later in New York, the runaway marriage, the happy country life afterward, and the play-acting that hd been a pleasure and a recreation for the young wife and her sisters turned into a means of support when her husband lost his fortune.

Among the Sunday afternoon books were volumes of the London Art Journal that had, besides copies of a great many early Victorian

-----

p. 74

pictures and statues of no great merit, some old Italian masters and more from Van Dyck, Reynolds, Gainsborough and Turner. With them and the Cunningham Gallery as companions, it was like going home to go into the National Gallery and find the Titian “Bacchus and Ariadne” and the Rubens “Chapeau de Paille,” besides the Hogarths that I had read of and the Turner “Ulysses and Polyphemus” that I had seen on a wall in a house where I used to go as a child. These Art Journals had all kinds of miscellaneous information—pictures from English history like Ward’s “James II Hearing of the Landing of the Prince of Orange,” Dr. Johnson in Lord Chesterfield’s waiting room, Hogarth’s portrait of Garrick and his wife, some of Thornbury’s scenes from the lives of English artists, and articles about Nuremberg and Albrecht Dürer’s grave.

“Emigravit” is the inscription on the tombstone where he lies;

Dead he is not, but departed, for the artist never dies.

-----

[p. 75]

A page from The Story of Little Kate: For a Good Girl.

[Text:]

LITTLE KATE.

Because she was so good a girl,

The little girls and boys;

Presented her a Christmas box,

Brim full of Pretty Toys.

-----

[p. 76 blank]

-----

p. 77

This was the beginning of an interest in Dürer and his work which has grown with the years. In one of my books—“Country Life”—there was a story called “The Adventures of a Pin.” At one period of its existence this pin had lived in a house where the family read aloud, among other books, “The Heir of Redclyffe.” This made me want to read it, too, and I found in it allusions to La Motte Fouqué’s “Sintram.” I soon discovered that it was founded upon the idea of Dürer’s Knight riding on undismayed by Death or the Devil, and it was a great pleasure to renew and extend my acquaintance with him through some of the woodcuts, and later through a book of his drawings and color sketches in the British Museum. It was, I think, my interest in the stage, in Garrick and Mrs. Siddons, and in Ward’s pictures that led me to a somewhat intimate acquaintance with eighteenth-century London, its men of letters and the actors who made it famous.

Charles Reade’s “Art, a Dramatic Tale,” which Ellen Terry made familiar to American playgoers as “Nance Oldfield,” was at that time published in weekly installments in the Liberator, an Abolition paper, and I remem-

-----

p. 78

ber the vivid picture of the eighteenth-century stage and the “Rival Queens,” Roxana and Statira, acted by Mrs. Bracegirdle and Mrs. Oldfield.

I can date my first reading of a novel by the place where I read it. When the little sister, seven and a half years to a day younger than I, was a few weeks old I was left with her and my mother, with instructions to call someone if they needed anything. As an inducement to be very quiet “The Lamplighter,” then new, was given me to read. The woes of little Gerty, her years in the old part of Boston when the kind lamplighter took her home, her life with the Grahams after his death, her journey up the Hudson, her heroic conduct and the romantic ending to the tale made a deep impression on me.

It was in the summer of the same year that I fell down a steep flight of stairs and, as a consolation for aches and bruises, was offered “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” I read it so many times that when I later heard Mrs. Stowe’s son tell “How Uncle Tom’s Cabin was Built,” repeating some of the scenes almost literally, I found so many of the phrases familiar and like household words that I could have helped

-----

p. 79

him if his memory had failed and told many things that he omitted. I could have described the cake that Aunt Chloe invited George to share, the difficulties thrown in the way of Haley starting in pursuit of Eliza, the scene at the senator’s and in the Quaker family and just how Cassy and Emmeline’s hiding place in Legree’s garret was made and furnished.

About this time I began to go to school. My mother had taught me to read and write and spell, besides a little arithmetic and geography, but with four children she had her hands full. So my brother and I were sent to a small, private school in a large, low, sunny room of an old-fashioned house, up whose yard we could go at recess to a blacksmith’s shop and watch him shoeing horses—a never-failing pleasure. I can smell my school reader now! There was an odor about the printer’s ink that always remained in it. It was “The Gradual Reader” with which I was already familiar in the older edition that my mother had used at school. Hers ended soon after “Thomas and his Little Sister,” but it included the little girl with whom I have always had the deepest sympathy—“The Bad

-----

p. 80

Seamstress.” Our friends Rollo and Lucy were in the book and “Self Denial”:

“I should like another, I think, mother,” said Frank, just as he had dispatched a large hemisphere of mince pie.

“Any more for you, my dear Harry?” said his mother.

“If you please. No, thank you, though,” said Harry, withdrawing his plate. “For,” thought he, “I have had enough and more than enough to satisfy my hunger, and now is the time for self-denial.”

One of the poems, “The Pretended Morning Drive,” was by Mary Howitt and a great favorite. I have found it recently in Mrs. Forbes’ “Favorites of a Nursery of Seventy Years Ago.” Others were less cheerful. “The Little Graves,” for instance, and

I like it not—this noisy street,

I never like, nor can I now.

In the additions of the later edition was:

There once was a man who contrived a balloon

To carry him whither? Why, up to the moon.

And years and years afterward when I climbed up from Salisbury to see where Old Sarum once had been, it was not on account of Sid-

-----

The Enchanted Cat.

From Prince Dorus.

-----

p. 81

ney Smith’s famous Rotten Borough article, but for the sake of the milestone:

Twelve miles to Old Sarum,

To Andover, nine

that undeceived the man when he thought he was in the moon.

After “The Gradual Reader” had been read through, the next step was to Swan’s “Grammar School Reader.” Up to that time I had not known much about poetry, barring Mother Goose and other infantile jingles, the poems in “The Gradual Reader” and Mrs. Turner’s “Daisy” and “Cowslip” verses in reprint; but this book opened a new world. Here was “The Deserted Village,” “The Pet Lamb,” “The Butterfly’s Ball,” “The Winged Worshippers,” “The Shepherd and the Philosopher,” “The Needless Alarm,” “Extracts from Beattie and Byron,” Wordsworth’s “Fidelity” and the poem that made the deepest impression of all, with long lines, solemn diction, and a wonderful choice of words—Gray’s “Elegy in a Country Churchyard,” whose opening stanzas I remember learning for the love of the sound of them. The story of “Eyes and No Eyes,” too, appealed to a

-----

p. 82

dawning sense of out-of-door beauty, and “The Boy without a Genius,” “Alexander and the Robber” and “Charles the Second and William Penn” have never been forgotten.

I have spoken of Wordsworth’s “Fidelity.” Somewhere, somehow I had found and liked better Scott’s version of the same tale, “Helvellyn.” It may have been in “Youatt on the Dog” or “The Dog and the Sportsman”—from which I learned every breed and every disease of dogs—but I think that I first saw it in Anna Cabot Lowell’s “Gleanings from the Poets.” The melody of it always haunted me. When later on I heard an Englishman answer “Catchedicam” to the question, “What is that mountain?” that we saw from Dunmail Raise, and an American girl said quickly, “He is making fun of us, he made up that queer name,” I knew that she had never read over and over:

But meeter for thee, gentle lover of Nature,

To lay down thy head like the meek mountain lamb;

When, wildered, he drops from some cliff huge in stature,

And draws his last sob by the side of his dam;

-----

[p. 83]

A page from Rhymes for the Nursery, 1837.

[Text:]

Go, naughty Ann, O go away,

You know you’ve not been good,

You’ve not been happy whilst at play,

And, heedless what your sisters say,

I don’t see how you should.

If little girls will peevish get,

And quarrel whilst at play

If they will learn to pine and pet,

To grow dissatisfied and fret,

This is the only way,

-----

[p. 84 blank]

-----

p. 85

And more stately thy couch by the desert lake lying,

Thy obsequies seen by the gray plover flying,

With one faithful friend but to witness thy dying

In the arms of Helvellyn and Catchedicam.

The book had been passed on to Jenny by an older sister, who being a Young Lady and going to Evening Parties, had no more use for school books. I used to borrow it when lessons were done to find a poem to repeat or to lose myself in the pages. They had a wide range, form “Busy, curious, thirsty fly” to “The Ancient Mariner.” The poem that I loved best was Lockhart’s “Lamentation for Celin.” I cannot look at the book now without seeing the mournful procession at the Vega Gate and hearing the slow tread of the horses, the wailing of the black-veiled sisters, the beat of the muffled drums, the shriek of the old nurse, all lamenting for “Granada’s darling knight,” lying dead with black crusted blood on his armor.

We had some dearly loved books that some older cousins had outgrown, books of the early forties. Among them was “The Crofton Boys,” Masterman Ready” and “The Fairy

-----

p. 86

Cabinet”—a little book bound in blue, translated from some of the “Cabinet de Fées.” It had “The Blue Bird” and “Finetta Cindretta.” The two lines that the Princess says to the bird,

Blue Bird, thou of Time’s own hue,

Haste thee to thy mistress true,

are in no other edition. There were, too, some volumes of Parley’s Magazine, with Miss Leslie’s “Week of Idleness” and stories of the boyhood of noted men. Knowing “The Crofton Boys” it was a great pleasure, long years afterward, to look out of the upper windows of a hotel just off Fleet Street and see “the leads” and watch the streamers going by on the Thames. One of the cousins’ books was, as it remembered it, a volume of Coleman’s Magazine, but I tried in vain to find it under that title in the Boston Public Library. In it were Tennyson’s “May Queen,” “Piping down the Valleys Wild” and Hunt’s “Abou Ben Adhem.” There were riddles, too, and puzzles, Hawthorne’s “Daffy-down-Dilly” and some other good stories. I did not get a copy of it until one Christmas, when a children’s librarian several hundred miles

-----

[p. 87]

From The History of Johnny Gilpin.

-----

[p. 88 blank]

-----

p. 89

away, who knew nothing of my search for the magazine, sent me a package of old books that she could not use and among them was my old friend, bound under the title “The Boys’ and Girls’ Annual.”

A school reader with a green cover and a sheepskin back came also from the cousins. I do not remember the title nor the name of the compiler, but I do recall that in it I made acquaintance with three famous poems—“John Gilpin,” “The Battle of Blenheim” and “The Cataract of Lodore.” What a “trainband captain eke” was I did not know, nor did I ask, for I had a way of keeping to myself whatever puzzled me, but Cheapside and Islington were two more of the places which I must see in London, and I had firm faith that Lodore was always doing everything that Southey said. Fortunately this faith has never been disturbed, for, instead of trickling over bare rocks as some travelers have described it, the cataract when I saw it was behaving even better than in the photographs, pouring masses of white foam into Derwentwater.

Not far from the slave seats in the gallery corner of the old, square, white, slender-

-----

p. 90

steepled church where Theodore Parker had preached for several years in the days when some of the Brook Farm used to listen to him every Sunday, there was a bookcase which must have held two or three hundred volumes, the library for the Sunday School, which was open on Sunday mornings every year from May to November, not in winter from the difficulty of heating the church in the early mornings. There were in it, as far as I can remember, no memoirs of children who died young—indeed I never saw one until after I grew up. My especial favorites there were two fat volumes, “Howitt’s Tales” and “Howitt’s Stories,” in one of which the heroine had for tea “hot pikelets,” which I afterward found in Derbyshire. Another, “Little Coin, Much Care,” was more real than ever when I saw the half-burned ruins of Nottingham Castle. The best of all was “Strive and Thrive,” the story of a widow and her children who kept a little shop in London. The daughter, who had learned to make designs for wall-paper, had one of the designs stolen and later identified by a mouse peeping from behind an acanthus leaf that she had sketched in the British Museum.

-----

[p. 91]

From The History of Goody Two Shoes, 1852.

[Text:]

Goody Two Shoes so clever,

She set up a School,

To arise with the skylark,

Was always her rule.

-----

[p. 92 blank]

-----

p. 93

In our village street was a large house where two sisters used to live, in an atmosphere of old-fashioned elegance. Going into the hall, with its crimson-carpeted winter parlor on the south, its blazing fire with the ladies sitting before it with little screens to shield their faces, was like walking into a book. So was the entrance in summer into the north parlor, cool and dark, with a green, mossy carpet and the portrait of the Beautiful Lady in low-necked, crimson velvet dress and gauzy scarf, with her hand on a stair rail. She kept her beauty, even when her hair was white, and with it her love of books. Her room upstairs was fairly crammed with them, and a bookseller in town had a standing order to send her whatever was best worth reading. She was very generous, too, in lending and in giving it to her friends. I have several books of later years with her name in them, that she passed on to me. One day she lent me a volume, not new, that she thought would please a bookish little girl. It was the first edition of Drake’s poems with “The Culprit Fay,” which I read with great delight. The music of the verse, the descriptions and the fairy

-----

p. 94

tale all combined into a new and charming whole. At another time she gave me Henrik Hertz’s “King Rene’s Daughter,” a romantic little play of much sweetness which has been a rôle to more than one great actress and is still a favorite with amateurs, a play entirely innocent and idyllic.

One day I found in our attic a shabby old copy of “Pickwick” in two volumes. I read it, then “David Copperfield,” which I have yet, incomplete and with covers dropping off after being read so many times by every member of the family. “The Christmas Carol” was read in school once by one of the teachers as a consolation for a hoped-for half holiday that was not granted. Not long after, the Beautiful Lady lent it to me in the first edition with colored plates.

I got my first idea of an English dramatic performance, the Christmas mumming play, from the Warner sisters, whose novels and, later, children’s books, are crammed with theology and sickly sentiment. Their “Mr. Rutherford’s Children” is full of an old-fashioned fragrance and shows the happy, well-ordered life of two little sisters in their uncle’s country house. In “Carl Krinken and His

-----

From The Token, 1830.

-----

p. 95