Artists illustrating early works on fossils were at a disadvantage. If they wanted to show the actual creature, they had no model. If they wanted to picture the fossils, they often still had no model. So artists turned to earlier illustrations.

Trying to identify the originals of illustrations is like trying to zero in on in just what millisecond the Big Bang occurred. Illustrators copied from illustrators who copied from other illustrators. However, Martin J. S. Rudwick’s readable and lushly illustrated Scenes From Deep Time: Early Pictorial Representations of the Prehistoric World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992) helps to set the illustrations in early American works for children in context. Many of the illustrations appear to have been copied from Gideon Mantell’s The Wonders of Geology, which was published in London in 1838 and in the United States in 1839. Others originated in Peter Parley’s Wonders of Earth Sea and Sky, published in London by Darton &; Clark in 1837 and reprinted by Goodrich for the American audience in 1840.

In identifying the sources of a number of the illustrations, I’ve relied heavily on Rudwick’s book. Luckily, the Darton book is available in microform, as part of the Opie Collection of Children’s Books. The Mantell is available online at google books. Still, some of the identifications are preliminary and a bit cursory.

A list of the illustrations in the transcribed pieces organized by subject appears at the end of this page.

- 1808: reconstruction of the skeleton of a Palaeotherium, by Georges Cuvier (Rudwick, p. 35). Reworked in Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky. London: Darton &; Clark, 1837 (p. 23). Reworked in Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky. NY: S. Colman, 1840 (p. 18).

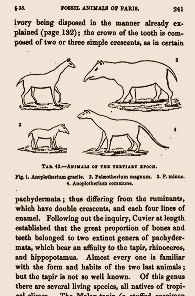

- 1822: outlines of two Palaeotherium and two Anoplotherium by Charles Laurillard from Georges Cuvier, Researches on Fossil Bones, 2nd ed. (Rudwick, p. 37). Reworked in American edition of Gideon Mantell, The Wonders of Geology, 1839, vol 1, p. 214. This was reworked in Wonders of Geology, 1845; and “Wonders of Geology,” Robert Merry’s Museum, 1848.

- 1824: plesiosaur skeleton by William Conybeare from “On the Discovery of an Almost Perfect Skeleton of the Plesiosaur,” Transactions of the Geological Society of London (Rudwick, p. 43). Georges Cuvier (Rudwick, p. 35). Reworked in Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky. London: Darton &; Clark, 1837 (p. 15). Reworked in Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky. NY: S. Colman, 1840 (p. 14); and “Wonders of Geology,” Robert Merry’s Museum, 1842.

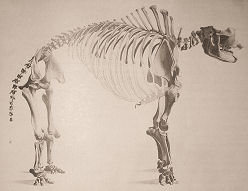

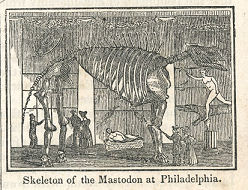

- 1826-1828: mastodon skeleton in Charles Willson Peale’s museum, drawn by Titian Ramsay Peale II in 1821, published in American Natural History, by John D. Godman, 1826-1828 (Edgar P. Richardson, Brooke Hindle, and Lillian B. Miller. Charles Willson Peale and His World. NY: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1982; p. 121). Possibly reworked in The First Book of History, 1831; The Child’s Own Book of American Geography, 1832; Peter Parley’s Tales about the State and City of New York, 1832.

- 1834: ichthyosaurus from Thomas Hawkins. Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri, Extinct Monsters of the Ancient Earth; also appears in British edition of Gideon Mantell, The Wonders of Geology, vol 2, p. 432. Reworked in “Letters About Geology,” The Student magazine, 1853.

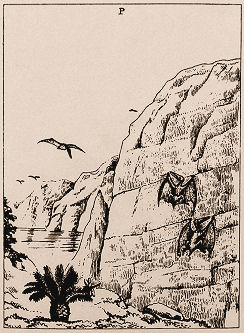

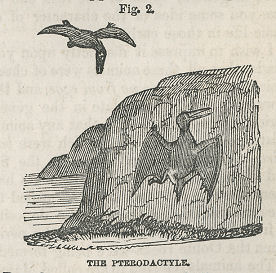

- 1836: pterodactyls clinging to a cliff from William Buckland, Geology and Mineralogy (Rudwick, p. 69). Reworked with one fewer pterosaur in “Letters About Geology,” The Student magazine, 1853.

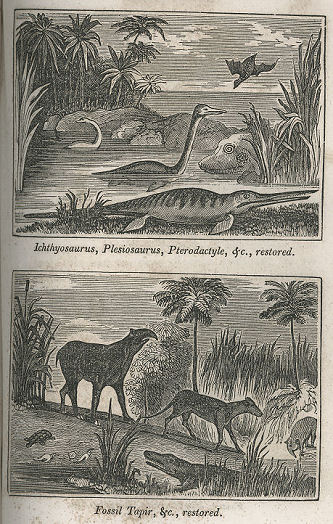

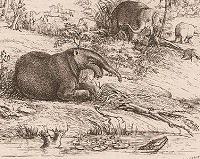

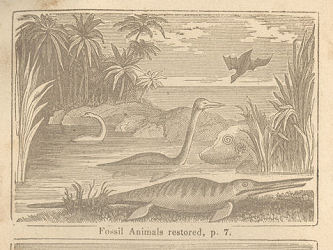

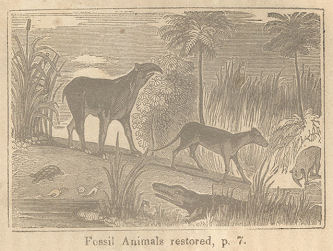

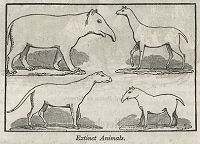

- 1837: landscapes (lithographs or mezzotints) from Georges Cuvier (Rudwick, p. 35) and Henry De la Beche (Rudwick, p. 57). Reworked in Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky. London: Darton &; Clark, 1837 (plates 1 &; 2; see also Rudwick, p. 75); both labeled “Extinct Animals”. Reworked as wood engravings in Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky. NY: S. Colman, 1840; and Wonders of Geology, 1845.

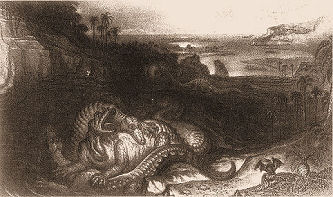

- 1838: “The Country of the Iguanodon,” by John Martin, in Gideon Mantell, The Wonders of Geology (Rudwick, p. 79). Reworked by Hammatt Billings as wood engraving “The Iguanodon,” Robert Merry’s Museum, 1842.

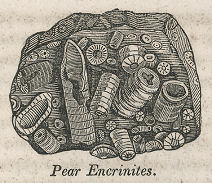

- 1838: lily crinoid from British edition of Gideon Mantell, The Wonders of Geology, vol 2, p. 419. Reworked in Samuel Goodrich, Wonders of Geology, 1845.

- 1838: crinoids from British edition of Gideon Mantell, The Wonders of Geology, vol 2, p. 513. Reworked in Samuel Goodrich, Wonders of Geology, 1845.

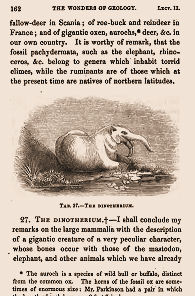

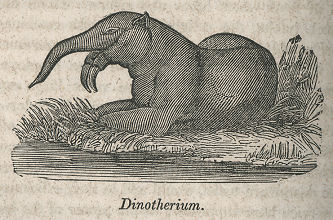

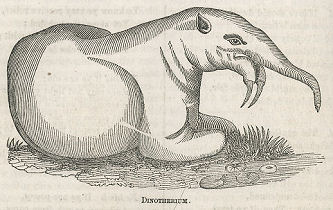

- 1839: dinotherium from American edition of Gideon Mantell, The Wonders of Geology, vol 1, p. 162. Reworked in Samuel Goodrich, Wonders of Geology, 1845. Another reworking in “Letters About Geology,” The Student magazine, 1853.

in American Natural History, by John D. Godman (1826-1828), from a drawing by Titian Ramsay Peale II (1821). [image from Edgar P. Richardson, Brooke Hindle, and Lillian B. Miller. Charles Willson Peale and His World. NY: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1982; p. 121]

The image resembles one by Georges Cuvier in his Recherces sur les ossemens fossiles [in Stanley Hedeen. Big Bone Lick: The Cradle of American Paleontology. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2008; p. 98]

in the discussion of Charles Willson Peale’s museum in The First Book of History (1831), by Samuel Griswold Goodrich; Goodrich also used the woodcut in The Child’s Own Book of American Geography (1832) and—thanks to some creativity—in Peter Parley’s Tales about the State and City of New York (1832)

in the American edition of The Wonders of Geology, by Gideon Mantell (1839); it very much resembles one by Rudolf Hofmann and Ludwig Becker which had appeared in 1836:

[image from Rudwick, p. 70]

in Wonders of Geology, by Samuel Goodrich (1845)

in “Letters About Geology,” by “Professor Pickaxe” (1853)

in the British edition of The Wonders of Geology, by Gideon Mantell (1839)

from Wonders of Geology, by Samuel Goodrich (1845)

in the British edition of The Wonders of Geology, by Gideon Mantell (1839)

from Wonders of Geology, by Samuel Goodrich (1845)

in Geology and Mineralogy, by William Buckland (1836); two pterosaurs cling to a cliff face while another flies in from the back [image from Rudwick, p. 69]

“Letters About Geology,” by “Professor Pickaxe” (1853); the clinging pterosaur appears to have been copied from the one on the right in the original

"Extinct Animals,” from Peter Parley’s Wonders of Earth, Sea, and Sky, London: Darton &; Clark, 1837 [image from Rudwick, p. 75]

"Fossil Animals restored,” from Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky, NY: S. Colman, 1840

"The Country of the Iguanodon,” by John Martin, in Gideon Mantell, The Wonders of Geology. Preying on one reptile, the mighty (pudgy) iguanodon is attacked by another, as an excited pterodactyl looks on; the Cretaceous is a violent place. [image from Rudwick, p. 79]

"The Iguanodon,” by Hammatt Billings, in Robert Merry’s Museum (1842). Alone, the mighty iguanodon (much slimmer) roars to the sky; the little pterodactyl has been moved from earth to sky, though the wings are pretty much in the same position.

The pterodactyl is outlined.

in the American edition of The Wonders of Geology, by Gideon Mantell (1839); it is based on outlines of two Palaeotherium and two Anoplotherium by Charles Laurillard, from Georges Cuvier, Researches on Fossil Bones, 2nd ed. (1822):

[image from Rudwick, p. 37]

from Wonders of Geology, by Samuel Goodrich (1845) The images are reversed, as if the artist copied the Mantell illustration directly onto the block and engraved it; the image prints in reverse.

unnumbered, unlabelled, and unnamed, in “Wonders of Geology,” by William Buckland, in Robert Merry’s Museum (1848)

- ancient landscapes: Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky (1840). “Wonders of Geology” (Robert Merry’s Museum; 1842). The Wonders of Geology, by Samuel Goodrich (1845). “Letters About Geology,” by “Professor Pickaxe” (The Student; 1853).

- buckler fish: “Wonders of Geology” (The Schoolmate; 1852).

- crinoids: The Wonders of Geology, by Samuel Goodrich (1845). “Wonders of Geology” (The Schoolmate; 1852).

- dinotherium: The Wonders of Geology, by Samuel Goodrich (1845). “Wonders of Geology” (The Schoolmate; 1852). “Letters About Geology,” by “Professor Pickaxe” (The Student; 1853).

- "human footprints": “Fossil Foot-Prints” (Young People’s Mirror; 1849).

- ichthyosaurus: Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky (1840). “Letters About Geology,” by “Professor Pickaxe” (The Student; 1853). skeleton: Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky (1840). “Wonders of Geology” (Robert Merry’s Museum; 1842). “Wonders of Geology” (The Schoolmate; 1852).

- iguanodon: “Wonders of Geology” (Robert Merry’s Museum; 1842). iguana, instead: “Letters About Geology,” by “Professor Pickaxe” (The Student; 1853).

- Irish elk skeleton: Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky (1840). The Wonders of Geology, by Samuel Goodrich (1845).

- mastodon skeleton: “The Mammoth” (Robert Merry’s Museum; 1841). The Wonders of Geology, by Samuel Goodrich (1845).

- megatherium skeleton: Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky (1840). “The Picture Gallery: Organic Remains” (Youth’s Cabinet; 1841). The Wonders of Geology, by Samuel Goodrich (1845). “Wonders of Geology” (The Schoolmate; 1852). “Letters About Geology,” by “Professor Pickaxe” (The Student; 1853).

- Palaeotherium; Anoplotherium: Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky (1840). “Wonders of Geology” (Robert Merry’s Museum; 1842). The Wonders of Geology, by Samuel Goodrich (1845). “Wonders of Geology,” by William Buckland (Robert Merry’s Museum; 1848).

- plesiosaur: Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky (1840). “Wonders of Geology” (Robert Merry’s Museum; 1842). “Wonders of Geology” (The Schoolmate; 1852). skeleton: “Wonders of Geology” (Robert Merry’s Museum; 1842). The Wonders of Geology, by Samuel Goodrich (1845).

- pterosaur; pterodactyl: Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky (1840). “Wonders of Geology” (Robert Merry’s Museum; 1842). “Letters About Geology,” by “Professor Pickaxe” (The Student; 1853). skeleton: Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky (1840). “Wonders of Geology” (Robert Merry’s Museum; 1842). The Wonders of Geology, by Samuel Goodrich (1845).

- shells: “The Picture Gallery: Organic Remains” (Youth’s Cabinet; 1841). The Wonders of Geology, by Samuel Goodrich (1845).

- tapir: Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky (1840). “Wonders of Geology” (Robert Merry’s Museum; 1842). “Wonders of Geology” (The Schoolmate; 1852).

- trilobite: “The Picture Gallery: Organic Remains” (Youth’s Cabinet; 1841). “Wonders of Geology” (The Schoolmate; 1852).

- vegetation: Peter Parley’s Wonders of the Earth, Sea, and Sky (1840). “Wonders of Geology” (The Schoolmate; 1852). annularia: “The Picture Gallery: Organic Remains””(Youth’s Cabinet; 1841). ancient palms: The Wonders of Geology, by Samuel Goodrich (1845)