“Deer Hunting,” by Simon Sassafras (from Robert Merry’s Museum, May 1850; pp. 133-134)

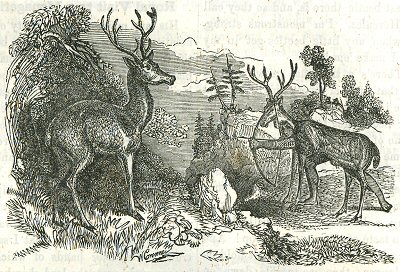

That’s a very confiding, unsuspicious deer in the picture. He never read the fable of the ass in the lion’s skin, or he might have been more on his guard. Our readers probably have sharper eyes than he, and will observe that the deer in the distance has six legs, two of which are copper colored, besides two heads, the one horned and the other tattooed. He seems also to be singularly skilled in the use of the crossbow. Our friend in the foreground looks on and smiles. Poor simpleton!

Yet that’s the way they did for many long years in this country, while the red men were yet masters of its soil, its forests, and rivers. The manner of proceeding was this: An Indian carrying a bow in his hand, and on his shoulders the horns and parts of the skin of a deer, steals quietly in among a herd who usually pay but little attention to the intrusion. From time to time he rubs the horns against his bow, imitating the gestures peculiar to the animal. He approaches by degrees, raising his legs very slowly, but setting them down suddenly, after the manner of a deer. If any of the herd leave off feeding to gaze upon this extraordinary phenomenon, it instantly stops and the head begins to play its part by licking its shoulders and performing other necessary movements. In this way the hunter attains the very centre of the troop without exciting suspicion, and has leisure to single out the fattest. The arrow flies, the victim falls, and the herd scampers off. The hunter trots after them, fitting another arrow to his bow as he runs. In a short time the poor animals halt to ascertain the cause of

-----

p. 133

their terror: the foe stops at the same instant and greets the gazers with a second fatal discharge. The consternation of the deer increases, they run to and fro in the utmost confusion, and sometimes a great part of the herd is destroyed within the space of a few hundred yards.

When the white men came to America, they too wanted to learn the trick—as if they didn’t know quite enough already, with their fire water, glass beads, and pewter money. The Indians imparted the secret to the pale faces, and taught them the art of hunting the deer. The engraving represents a native in the act of giving his class a lesson. A quick eye may detect the pupils peering out from among the trees and bushes in the background. We can see six; no doubt some of our friends who are smart at addition will be able to make out a dozen or more.

Our conscience would go against eating any venison captured in this way. A fair field and no quarter, say we! The deer has got four as fine legs as ever were made, to scamper with, and we should like to see him have a chance to use them, before any lurking shot lays him low. If flying from one foe, he runs into the range of another one’s fire; if his horns get entangled in a thicket, or a rolling stone sends him head over heels into a swamp—these are the fortunes of war, and as he can’t help it, neither can we. But to come out with one of his relations’ hide on your back, and pretend to be his mother or his aunt, and then aim, and draw, and let fly—we think this mean, and leave it for persons who’ve got nothing better to do. We could not eat any so ill-gotten venison. It would be apt to go down the wrong way. Currant jelly and a blaze would only make the matter worse.