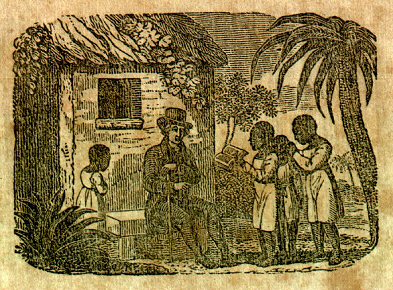

The front cover for 1836 featured a white man teaching young black boys to read.

-----

[cover p. 2; inside front cover]

THE SLAVE TRADER.

From ocean’s wave a wanderer came,

With visage tanned and dun;

His mother, when he told his name,

Scarce knew her long lost son;

So altered were his face and frame,

By the ill course he had run.

“There’s blood upon my hands,” he said,

“Which water cannot wash;

It was not shed where warriors bled,

But dropped from the gory lash,

As I whirled it o’er and o’er my head,

And with each stroke left a gash.

“With every stroke I left a gash,

While negro blood sprang high,—

And now all ocean cannot wash

My soul from murder’s dye;

Not e’en thy prayer, dear mother, stop

That woman’s wild death-cry!

“Her cry is ever in my ear

And will not let me pray,

Her look I see—her voice I hear—

As when in death she lay,

And said, ‘With me thou must appear,

On God’s great Judgment Day!’ ”

-----

[p. 1]

SLAVE’S FRIEND.

==================================================

NO. XI.

==================================================

SLAVE VESSELS.

Rufus. What Ship is that?

Seth. That is not a Ship, dear brother, but a Brig. Her name is Saint Nicholas.

Rufus. Is that the slaver?

-----

p. 2

Seth. She is supposed to be a slave-vessel.

Rufus. I heard that the collector of New-York had seized that brig, just as she was ready for sea, and that the captain and part of the crew had been taken before the United States Judge. What made them think it was a slaver?

Seth. She was built very sharp, so as to sail fast, and take but little cargo. That shows she was not intended for a merchant-ship. The English ships of war cruise on the coast of Africa, and they will capture slave-ships if they do not sail very fast. Then she had large water tanks, that would hold upwards of one hundred and twenty gallons of water each. This shows that they expected to have a large number of people on board to drink this water. Merchant vessels take water in casks. There were also cannon, muskets, cutlasses, and pistols on board.

Rufus. But I heard some one say she

-----

p. 3

might belong to the navy, or be a privateer?

Seth. If she had been either they would have shown their commission. Besides, there were iron-gratings for the hatchways.

Rufus. What use could they make of the gratings?

Seth. They put them over the hatchway, so that light and air can go down into the hold of the vessel, and the slaves can still be kept from escaping. Slave vessels always have them. And the witnesses who had seen slave-vessels, had no doubt from her general appearance that this brig was one. The cargo consisted of such goods as the slave-traders take to Africa to exchange for slaves. There were, beside other articles, twenty- five boxes of muskets, and five hundred kegs of powder! they can buy a slave in Africa for a musket, or a flask of gunpowder.

Rufus. O, dreadful! What wicked men! But could not they make the

-----

p. 4

sailors tell where they were going? And what they were going for?

Seth. No, they would not confess any thing before the Judge. But two of them, who were Italians, had told a few days before, that they were going to Africa “after nigger,” and when they had brought them to the island of Cuba, they were going to sell them. So the Judge sent these two sailors to prison, and they will be tried, and as there was not evidence enough to commit the rest they were set at liberty.

Rufus. What will be done to such people, and to the brig, if the men are proved to be guilty?

Seth. The vessel will be confiscated, that is taken from them; besides, they will have to pay a large fine, and be put in prison. Now, Rufus, what will you say when I tell you this brig was built at Baltimore, and that people in this country join with wicked men of other nations, in fitting out vessels for the slave-trade, every year?

-----

p. 5

Rufus. What will I say? Why, that it is a disgrace to this country, and a horrible wickedness in the sight of God. I read the other day about

These wicked brokers in the trade of blood,

Who buy, and sell, and steal, for gold.

Seth. I have read also what Jonathan Edwards said, forty-three years ago,—“To steal a man, or to rob him of his liberty, is a greater sin than to steal his property, or to take it by violence. And to hold a man in a state of slavery, who has a right to his liberty, is to be every day guilty of robbing him of his liberty, or of man-stealing.” I wish that all ministers, now a days, would preach the truth so faithfully. Then, as your father said yesterday, slavery would soon come to an end; and when there is no slavery there will be no slave-trade.

James. I have just heard that the St. Nicholas has gone to sea! The grand jury have indicted the captain; but the consignees had given bonds for a quarter of the brig, and so away went the pirate-brig!

-----

p. 6

[The illustration is oriented sideways in the original, in order to fit on the page.]

THE GOOD OLD MAN.

In Slave’s Friend, No. VI, there was an account given of a good old man,

-----

p. 7

who used to hear some children read, and give them little picture-books. Some wicked boys used to pelt these children with stones, and call them niggers, so that they did not love to go to school. Therefore, this good old gentleman used to teach them, in front of his cottage. I thought my little readers would like to see the picture once more.

LETTER FROM AN INFANT SLAVE TO THE CHILD OF ITS MISTRESS—BOTH BORN ON THE SAME DAY.

Baby! be not surprised to see

A few short lines coming from me,

Addressed to you;

For babies black of three months old

May write as well, as I’ve been told,

Some white ones do.

There are some things I hear and see,

Which very much do puzzle me,

Pray don’t they you?

For the same day our lives began,

And all things here beneath the sun,

To both are new.

-----

p. 8

Baby, sometimes I hear you cry,

And many run to find out why,

And cure the pain;

But when I cry from pains severe,

There’s no one round who seems to hear,

I cry in vain.

Except it be when she is nigh,

Whose gentle love, I know not why,

Is all for me;

Her tender care soothes all my pain,

Brings to my face those smiles again,

She smiles to see.

With hunger faint, with grief distressed,

I once my wretchedness expressed,

With urgent power;

Some by my eloquence annoyed,

To still my grief rough blows employed;

Oh, dreadful hour!

When first thy father saw his child,

With hope, and love, and joy, he smiled—

Bright schemes he planned;

Mine groaned, and said with sullen brow,

Another slave is added now

To this free land.

Why am I thought so little worth,

You prized so highly from your birth?

Tell, if you know;

-----

p. 9

Why are my woes and joys as nought,

With careful love your’s [sic] shunned or sought?

Why is it so?

My own dear mother, it is true,

Loves me as well as your’s [sic] does you;

But when she’s gone,

None else to me a care extends;

Oh, why have you so many friends,

I only one?

Why must that one be sent away,

Compelled for long, long hours to stay

Apart from me?

I think as much as I she mourns,

And is as glad when she returns,

Her child to see.

One day I saw my mother weap,

A tear fell on me when asleep,

And made me wake;

Not for herself that tear was shed,

Her own woes she could bear, she said,

But for my sake.

She could not bear, she said, to think,

That I the cup of woe must drink,

Which she had drunk;

That from my cradle to my grave,

I too must live a wretched slave,

Degraded, sunk.

-----

p. 10

Her words I scarcely understood,

They seemed to speak of little good,

For coming years;

But joy with all my musings blends,

And infant thought not far extends

Its hopes or fears.

I ponder much to comprehend

What sort of beings, gentle friend,

We’ve got among;

Some things in my experience,

Do much confound my budding sense

Of right and wrong.

Baby, I love you; ’tis not right

To love you less because you’re white;

Then surely you

Will never learnt o scorn or hate,

Whom the same Maker did create

Of darker hue.

Beneath thy pale uncolored skin,

As warm a heart may beat within,

As beats in me.

Unjustly I will not forget,

Souls are not colored white or jet,

In thee or me.

Your coming of the tyrant race,

I will not think in you disgrace,

Since not your choice;

-----

p. 11

If you’re as just and kind to me,

Through all our lives, why may not we,

In love rejoice?

E. T. C.

BAYLER COOLEY’S FAMILY.

This worthy man was a slave in Virginia. He earned money enough to purchase his freedom, and to buy a small piece of land on Long Island. The past winter he has been going around to beg for money to buy his wife, and some of his children, and to remove them to his little farm. He showed a paper like this:—

This is to certify, that we have agreed, for the accommodation of Bayler, to sell to him the said Bayler, his wife and five young children, namely, Lucy, Nancy, Charity, Charlotte, and Nelly, for the sum of seven hundred and fifty dollars, provided he shall call for them by the first of March next. Given under our hands this 10th day of December, 1835.

P. W. B.

J. R. B.

I had a desire to know the ages of these children, and what the slave-hold-

-----

p. 12

ers asked for each of them. So Mr. Cooley said that his wife’s name was Clara, and that they asked for her three hundred dollars. That Lucy was about ten years old, and the price for her was two hundred dollars. that Nancy was five, and they asked for her one hundred dollars. That Charity was three, and the price for her was fifty dollars; and that Charlotte and Nelly were twins, and will be two years old next May, if they live. The slave-holders asked for both these little girls one hundred dollars.

I asked him if he had any other children. He said, “yes, but they asked so much for them, I do not expect to be able to buy them.” John Albert is twenty-one years of age; Aurenia Ann is nineteen; Moses is fourteen; and Joshua is twelve.

-----

p. 13

LITTLE SLAVE’S COMPLAINT.

BY MONTGOMERY.

Who loves the little slave? Who cares

If well or ill I be?

Is there a living soul that shares

A thought or wish for me?

I’ve had no parents since my birth,

Brothers and sisters—none:

O, what is all this world to me,

Where I am only one!

I wake, and see the sun arise,

And all around me gay;

But nothing I behold is mine,

No—not the life of day!

No! not the very breath I draw—

These limbs are not my own;

A master calls me his by law,

My griefs are mine alone.

Ah, these they could not make him feel—

Would they themselves had felt

Who bound me to that man of steel,

Whom mercy cannot melt.

Yet not for wealth or ease I sigh,

All are not rich and great:

Many may be as poor as I—

But none so desolate.

-----

p. 14

For all I know have kin and kind,

Some home, some hope, some joy;

But these I must not look to find—

Who knows the colored boy?

The world has not a place of rest

For outcasts so forlorn—

’Twas all bespoken, all possest—

Long before I was born!

Affection, too, life’s sweetest cup,

Goes round from hand to hand;

But I am never ask’d to sup—

Out of the ring I stand!

If kindness beats within my heart,

What heart will beat again?

I coax the dogs,—they snarl and start,—

Brutes are as bad as men.

The beggar’s child may rise above

The misery of his lot,

The gipsy may be loved and love—

But I—but I must not.

Hard fare, cold lodgings, cruel toil,

Youth, health, and strength consume;

What tree could thrive in such a soil?

What flower so scathed could bloom?

-----

p. 15

Should I out grow this cripling work, [sic]

How shall my bread be sought?

Must I to other lads turn Turk,

And teach what I am taught?

O! might I roam with flocks and herds

In fellowship along!

O! were I once among the birds—

All wing, all life, all song!

Free with the fishes may I dwell,

Down in the quiet sea;

The snail in his cobcastled shell—

The snail’s a king to me.

For out he goes in April showers,

Lies snug when storms prevail,

He feeds on fruits, he sleeps on flowers—

I wish I was a snail.

No: never! do the worst they can,

I may be happy still;

For I was born to be a man—

And with God’s leave, I will.

We have altered the title of this sweet little poem, and a word or two in a few of the verses.—Ed.

-----

p. 16

INTERESTING ANECDOTE.

The following is from Mr. Birney’s newspaper, the Philanthropist, printed at New Richmond, Ohio.

A few days since a physician of Cincinnati,—called in to minister to one of the members of a respectable and pious family who are, by no means, abolitionists,—on leaving the house, presented to one of the little daughters a late number of [t]he “Slave’s Friend.” On calling again a day or two afterwards, he was informed by the mother, that she had been found weeping and apparently in great distress; and that on being asked to tell the cause of her tears, she said she could not help crying, when she thought of the poor little negro boy about whom she had been reading in her little book. This same little book was, after this, read by all the family.

-----

[inside back cover]

THE GOOD BOY.

One day I saw a crowd of boys in the street, looking at a white boy insulting a sweep who was rather larger than himself.

The white boy looked passionate, shook his fist in the colored boy’s face, swore at him, and tried to make him fight.

But the sweep stood erect, looked calm, and said nothing. At length the white boy, finding he could not get the sweep into a passion, ran away, and left him.

I could not but think how much more respectable the sweep appeared than the angry white boy; how much more he acted like Jesus Christ.

GOOD MEN.

A slave who had earned money enough to purchase his freedom, chose rather to secure his mother’s liberty.

“Strike me,” said a slave to his master, “but do not curse my mother.”

A white man beat his father, in the presence of a slave, who immediately took away a child of this unnatural son, saying, “I fear this child will learn to imitate his father.”

-----

[back cover]

CONTENTS.

Slave Vessels, … 1

The Good Old Man, … 6

Letters from an Infant Slave, … 7

Bayler Cooley’s Family, … 11

Little Slave’s Complaint, … 13

Interesting Anecdote, … 16

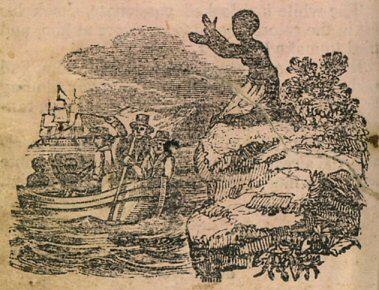

THE POOR MOTHER.

“HELP! oh help! thou God of Christians?

Save a mother from despair;

Cruel white men steal my children,

God of Christians! hear my prayer.

From my arms by force they’re rended,

Sailors drag them to the sea—

Yonder ship at anchor riding,

Swift will carry them away.["]