The Token, edited by Samuel Griswold Goodrich (Boston: Carter & Hendee, 1829)

-----

[engraved title page]

THE TOKEN

Boston

PUBLISHED BY CARTER AND HENDEE

1830.

D. Russell Prt.

-----

[printed title page]

THE TOKEN;

A

—

EDITED BY S. G. GOODRICH.

—

‘So, take my gift! ’T is a simple flower,

But perhaps ’t will wile a weary hour,

And the spirit that its light magic weaves,

May touch your heart from its simple leaves—

And if these should fail, it at least will be

A Token of love from me to thee.’

—

PUBLISHED BY CARTER AND HENDEE.

—

MDCCCXXX.

-----

[copyright page]

DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS, TO WIT:

District Clerk’s Office.

Be it remembered, that on the twentieth day of August, A. D. 1828, in the fiftyfourth year of the Independence of the United States of America, S. G. Goodrich, of the said district, has deposited in this office the title of a book, the right whereof he claims as proprietor, in the words following, to wit:—

‘The Token, a Christmas and New Year’s Present. Edited by S. G. Goodrich.

“So, take my gift! ’T is a simple flower,

But perhaps ’t will wile a weary hour,

And the spirit that its light magic weaves,

May touch your heart from its simple leaves—

And if these should fail, it at least will be

A Token of love from me to thee.”

In conformity to the act of the Congress of the United States, entitled ‘An act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies during the times therein mentioned;’ and also to an act entitled ‘An act supplementary to an act, entitled “An act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies during the times therein mentioned;” and extending the benefits thereof to the arts of designing, engraving, and etching historical and other prints.’

JNO. W[.] DAVIS,

Clerk of the District of Massachusetts.

-----

[p. iii]

PREFACE.

—

In presenting the third volume of the Token to the public, the editor may be allowed to say for himself and the publishers, that they have used their endeavours to make it worthy of the same liberal encouragement which has been extended to his predecessors. In the present advancing state of literature and the arts in this country, it has not been deemed sufficient merely to equal the volume of the last year. We have felt that it might be fairly expected that each number should surpass the preceding one, in whatever may constitute excellence in this species of publication. Accordingly we have sought to engage the first talents as well in the literary as the mechanical departments, to which we have added our own exertions, and now respectfully submit the result to the public.

The contributions are, as heretofore, all original, and by American writers.

-----

p. iv

The engravings are on steel. Eight of them are from original paintings, six of which are by American artists, and were executed for the work. The picture entitled ‘Sibyl,’ is from a painting belonging to Dr Binney of this city; ‘Grandfather’s Hobby’ is from a picture by Sully, after a design by King, in the possession of J. Fullerton, Esq. To these gentlemen our thanks are due for the loan of these pictures to the artists who copied them.

From the beginning it has been the design of the proprietors to make the Token strictly American. It is believed to be the only work of a similar kind, which has attained to any considerable distinction, that has employed in its composition, and the execution of its embellishments, American talent only. In waving [sic] the advantage which might be derived from the assistance of eminent English writers and artists, the publishers have relied upon the national feeling of the American public, to foster and sustain a work peculiarly their own. Hitherto the success of the experiment has been encouraging. The Token has not only been favorably received by those to whom it particularly appealed for support, but it has met with unexpected favor at

-----

p. v

the hands of foreign critics. In England, France, and Germany, many of the leading articles have been republished, and the work as a whole has drawn forth terms of commendation, not a little surprising, when it is taken into view how very recent are the first attempts to produce works of this kind in our country.

These remarks are made with no other view than to present such considerations to the public as may excite whatever degree of interest is due to our publication. For, notwithstanding the ready sale which has attended the former volumes, yet the Token has hitherto scarcely paid its expenses. From the published statements, as well in the English as in one of the American Souvenirs, we may safely state that the Token has been more costly to the publishers in proportion to the price at which it sells, than any similar work. It is true that the English publishers pay a higher price for their engravings, and also for the literary contributions. But the number of copies in their editions is twice or thrice that of the Token, and the price at which those annals of an equal number of engravings are sold, is about one third more. Could works of this sort find the same liberal encouragement with us as in England, as to price and

-----

p. vi

extent of sale, we are confident in the opinion, that ours would soon be in no respect inferior to those of London. In truth, reasons, founded upon our peculiar scenery, and upon the rich mines of poetic and legendary materials, which lie buried in our general and local history, together with the aptitude of our countrymen for the fine arts, could easily be assigned why we should ere long take the lead in this elegant class of publications.

There is another consideration which we venture to suggest, as a reason for hinting to our countrymen, that the Token not only asks for, but is dependent upon their liberality. The publishers of the English Souvenirs have their plates executed on steel. These are capable of producing an almost indefinite number of impressions. After having supplied their own market, therefore, they can still strike off a sufficient number of plates to supply America. Add to this, that the literary articles are also on hand, and the setting up of the types is already done. Thus, with reference to the American market, the English publisher can manufacture these works, without either the cost of engravings, the literary articles, or the composition of

-----

p. vii

the types; three items which will embrace at least one half of the whole expenses [sic] of such publications. Then let it be considered that the average duty paid on their importation, does not exceed twelve and a half per cent. ad valorem, and it is obvious, that not only English annuals, but all other works of a similar character published in England, may be introduced into the United States, at a far less relative cost than those of our own production.

But these are, perhaps, too grave topics for an introduction to a work like this. The young and the fair will of couse ‘skip’ them, and give us, as we hope, their good will and good wishes, without taking the trouble to pore over this dull prose. As to those difficult people, who must have a good reason for everything they do, we respectfully submit the foregoing hints, and hope they may find ‘in, on, or about them’ a conclusive argument for lending their support to our humble enterprise. If there is yet a third class who are not provided with a motive for becoming our patrons, we part with them, making the simple request that they will not pass us by until they have consulted the Sibyl.

-----

p. viii

With respect to the future, it is intended still to prosecute the publication of the Token, and every effort shall be made to raise its character for literary and mechanical excelence. The contributions of our friends are again solicited; and we request favorable excuses for any seeming neglect of those which they have already sent us. We have received many articles, well worthy of insertion, which, however, for various reasons, could not appear this year. Several of them will be printed in the next volume.

The subscriber proposes in future to assume the responsibility of the editorial department. It is proper to add, that in the preparation of the present volume, he has had the assistance of a gentleman, whose taste has largely contributed to whatever degree of merit it possesses. With no other pretensions than those which his experience as a publisher may furnish, he submits the present volume, and his future plan, to the public.

S. GRISWOLD GOODRICH.

Boston, September 1, 1829.

-----

[p. ix]

EMBELLISHMENTS.

—

1. Vignette Titlepage, engraved by J. Cheney, after a design by H. Inman … 1

2. Sibyl, engraved by J. Cheney, from a painting after Guido, belonging to Dr Binney … 31

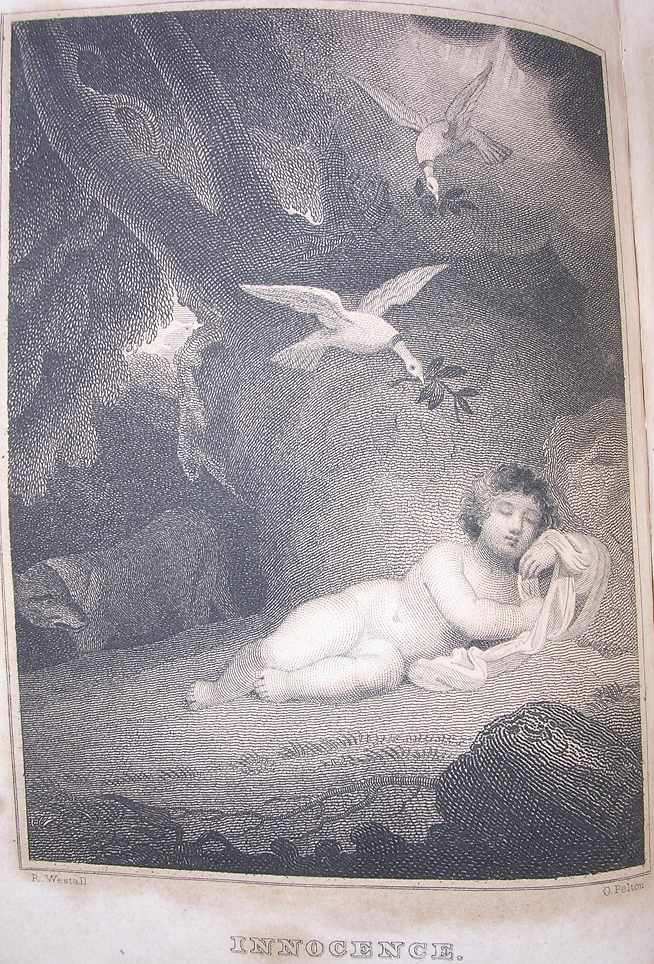

3. Innocence, engraved by O. Pelton, designed by R. Westall … 61

4. Doomed Bride, engraved by G. W. Hatch, from a painting, executed for S. G. Goodrich, by H. Inman … 91

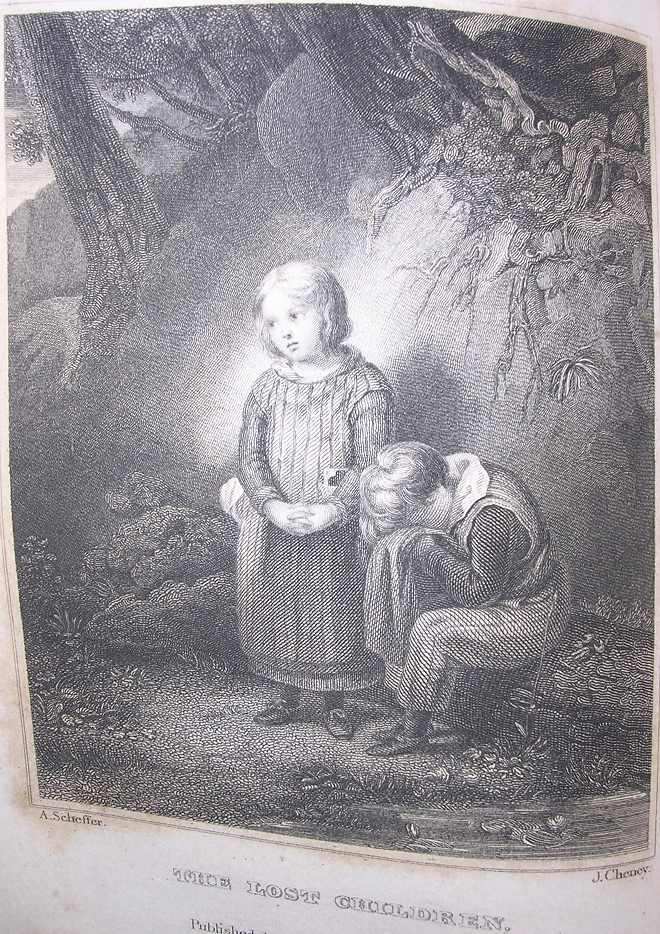

5. Lost Children, engraved by J. Cheney, designed by Scheffer … 117

6. Portrait of J. G. C. Brainard, engraved by J. B. Longacre, painted by E. Tisdale, for S. G. Goodrich … 121

7. Meditation, engraved by G. B. Ellis, designed by H. Fradelle … 151

8. Banks of the Juniata, engraved by G. B. Ellis, from a painting, executed for S. G. Goodrich, by Doughty … 1[9]5

9. Grandfather’s Hobby, engraved by E. Gallaudet, from a painting by T. Sully, after a design by C. B. King, belonging to J. Fullerton, Esq. … 233

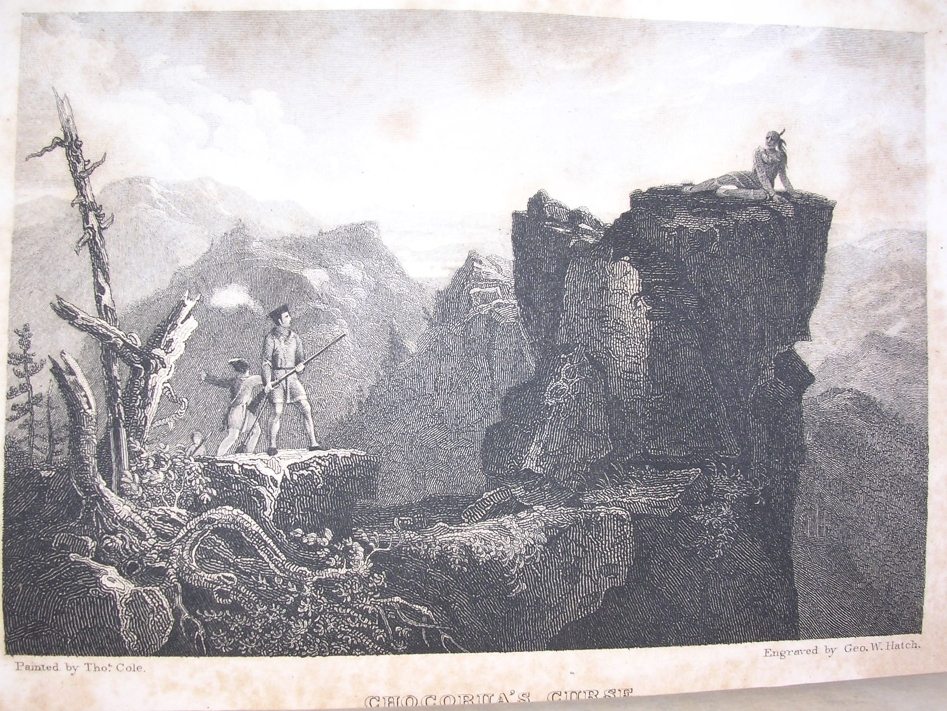

10. Chocorua’s Curse, engraved by G. W. Hatch, after a painting from nature (Corway Peak, New Hampshire), by T. Cole, executed for S. G. Goodrich … 257

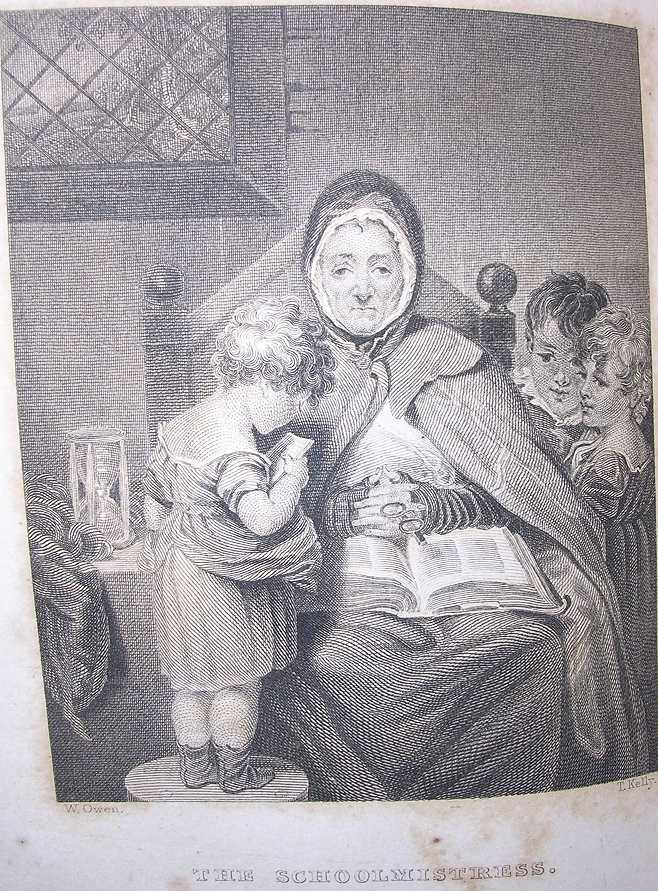

11. Schoolmistress, engraved by T. Kelly, after a design by W. Owen … 295

12. Genevieve, engraved by S. Andrews, designed by A. M. Huffman … 319

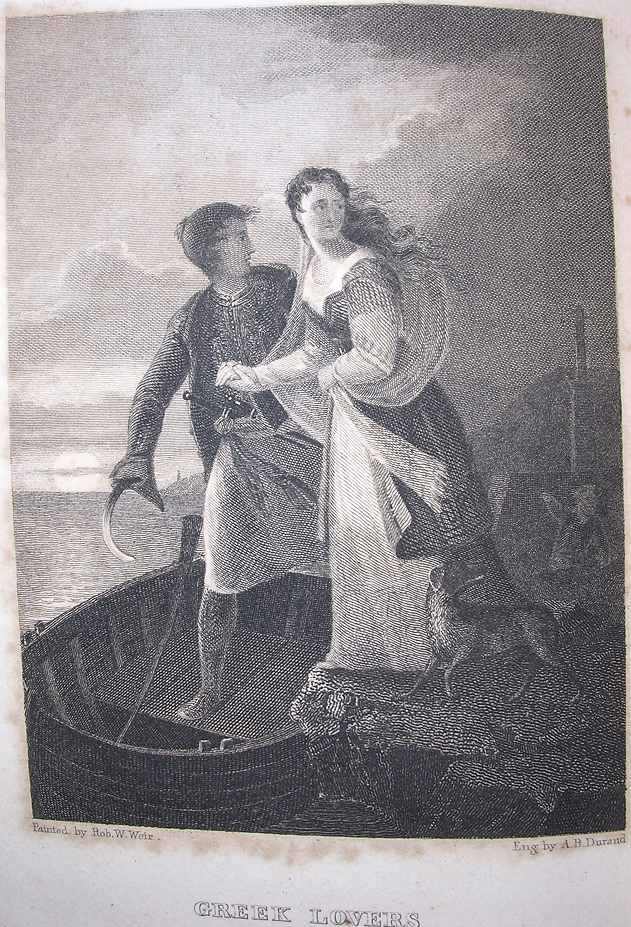

13. Greek Lovers, engraved by A. B. Durand, from a painting by R. W. Weir, executed for S. G. Goodrich … 327

-----

[p. x blank]

-----

[p. xi]

CONTENTS.

—

The Token … 13

The Sea—By F. W. P. Greenwood … 15

Napoleon—By Grenville Mellen … 28

The Sibyl—By N. P. Willis … 31

The Maniac—By S. G. Goodrich … 33

The Wounded Bird—By P. … 36

The Indian Fighter—By the Author of ‘Francis Berrian’ [Timothy Flint] … 37

To a Bride—By John W. Stebbins … 59

Innocence—By Grenville Mellen … 61

The Height of Impudence—By James Isaacs … 63

Destiny—By P. M. Wetmore … 84

The Three Ages of Life—By the Author of ‘Memoirs of a New England Village Choir’ [Samuel Gilman] … 85

The Doomed Bride—By Grenville Mellen … 91

Departure of the Eagle—By B. B. Thatcher … 113

A Thought—By G. … 116

The Lost Children—By N. P. Willis … 117

Snow—By E. W. T. … 119

On the Death of a Friend—By G. [Samuel Griswold Goodrich] … 120

To the Memory of J. G. C. Brainard—By Mrs Sigourney … 121

To Mrs Hemans—By G. B. C. … 124

The Young Provincial … 127

Lines—By Signora … 146

To a Wave—By J. O. Rockwell … 147

Songs of the Bees—By H. F. Gould … 149

-----

p. xii

The Sleep Walker [Samuel G. Goodrich] … 150

Meditation [Samuel G. Goodrich] … 151

Infidelity—By J. I***** [Robert C. Sands?] … 152

The Country Cousin—By the Author of ‘Hope Leslie’ [Catherine Maria Sedgwick] … 153

To —By P. … 194

The Juniata—By S. Griswold [Samuel G. Goodrich] … 195

The Unfinished Monument on Bunker Hill—By C. G. … 196

The Captain’s Lady—By James Hall … 197

Thoughts at Sea—By S. G. Goodrich … 211

Nulla nisi Ardua Virtus—by N***** [John Neilson, jr] … 212

To an Aul’ Stane—By Thomas Fisher … 213

The Wag-Water, a West Indian Sketch—By S. Hazard … 215

Grandfather’s Hobby [Samuel G. Goodrich] … 233

A Dream of the Sea—By W. G. Clark … 235

Legend of the Withered Man—By William L. Stone … 237

The Minstrel—By V. V. Ellis [John O. Sargent] … 255

Chocorua’s Curse—By the Author of ‘Hobomok’ [Lydia Maria Child] … 257

Lines [Samuel G. Goodrich] … 265

To — By N—s … 266

The Leaf—By S. G. Goodrich … 267

The Frosted Trees—By Alonzo Lewis … 269

The Huguenot Daughter—By Hannah Dorset … 271

A Dream … 294

The Schoolmistress—By Mrs Sigourney … 295

Ode to the Russian Eagle—By George Lunt … 297

The Utilitarian—By John Neal … 299

Genevieve—By N. P. Willis … 319

The Bubble—By J. O. Rockwell … 321

The Bugle—By Grenville Mellen … 323

Sketch—By J. P. Brace … 325

Greek Lovers [Samuel G. Goodrich] … 327

Extract—By John Pierpont … 329

-----

[p. 13]

THE TOKEN.

—

THE TOKEN.

REFERRING TO THE VIGNETTE TITLEPAGE.

The sportive sylphs that course the air,

Unseen on wings that twilight weaves,

Around the opening rose repair,

And breathe sweet incense o’er its leaves.

With sparkling cups of bubbles made

They catch the ruddy beams of day,

And steal the rainbow’s sweetest shade

Their blushing favorite to array.

They gather gems with sunbeams bright

From floating clouds and falling showers,

They rob Aurora’s locks of light

To grace their own fair queen of flowers.

-----

p. 14

Thus, thus adorned, the speaking rose

Becomes a Token fit to tell

Of things that words can ne’er disclose

And nought but this reveal so well.

Then take my flower, and let its leaves

Beside thy heart be cherished near,

While that confiding heart receives

The thought it whispers to thine ear.

—

-----

[p. 15]

THE SEA.

BY F. W. P. GREENWOOD.

—

— and thou, majestic main,

A secret world of wonders in thyself,

Sound his stupendous praise, whose greater voice

Or bids you roar, or bids your roarings fall.

THOMSON.

—

‘The sea is his, and he made it,’ cries the Psalmist of Israel, in one of those bursts of enthusiasm and devotion, in which he so often expresses the whole of a vast subject by a few simple words. Whose else indeed could it be, and by whom else could it have been made? Who else can heave its tides, and appoint its bounds? Who else can urge its mighty waves to madness with the breath and the wings of the tempest; and then speak to it again in a master’s accents, and bid it be still? Who else could have poured out its magnificent fulness round the solid land, and

‘Laid as in a storehouse safe its watery treasures by?’

Who else could have peopled it with its countless inhabitants, and caused it to bring forth its various

-----

p. 16

productions, and filled it from its deepest bed to its expanded surface, filled it from its centre to its remotest shores, filled it to the brim with beauty, and mystery, and power? Majestic ocean! Glorious sea! No created being rules thee, or made thee. Thou hearest but one voice, and that is the Lord’s; thou obeyest but one arm, and that is the Almighty’s. The ownership and the workmanship are God’s; thou art his, and he made thee.

‘The sea is his, and he made it.’ It bears the strong impress of his greatness, his wisdom, and his love. It speaks to us of God with the voice of all its waters; it may lead us to God by all the influences of its nature. How, then, can we be otherwise than profitably employed while we are looking on this bright and broad mirror of the Deity? The sacred scriptures are full of references to it, and itself is full of religion and God.

‘The sea is his, and he made it.’ Its majesty is of God. What is there more sublime than the trackless, desert, all surrounding, unfathomable sea? What is there more peacefully sublime than the calm, gently heaving, silent sea? What is there more terribly sublime than the angry, dashing, foaming sea? Power, resistless, overwhelming power, is its attribute and its expression, whether in the careless, conscious grandeur of its deep rest, or the wild tumult of its excited wrath.

-----

p. 17

It is awful when its crested waves rise up to make a compact with the black clouds, and the howling winds, and the thunder, and the thunderbolt, and they sweep on in the joy of their dread alliance, to do the Almighty’s bidding. And it is awful, too, when it stretches its broad level out to meet in quiet union the bended sky, and show in the line of meeting the vast rotundity of the world. There is majesty in its wide expanse, separating and enclosing the great continents of the earth, occupying two thirds of the whole surface of the globe, penetrating the land with its bays and secondary seas, and receiving the constantly pouring tribute of every river, of every shore. There is majesty in its fulness, never diminishing and never increasing. There is majesty in its integrity, for its whole vast substance is uniform; in its local unity, for there is but one ocean, and the inhabitants of any one maritime spot may visit the inhabitants of any one maritime spot may visit the inhabitants of any other in the wide world. Its depth is sublime; who can sound it? Its strength is sublime; what fabric of man can resist it? Its voice is sublime, whether in the prolonged song of its ripple or the stern music of its roar; whether it utters its hollow and melancholy tunes within a labyrinth of wave-worn caves; or thunders at the base of some huge promontory; or beats against a toiling vessel’s sides, lulling the voyager to rest with the strains of its wild monotony; or dies away with the calm and dying

-----

p. 18

twilight, in gentle murmurs on some sheltered shore. What sight is there more magnificent than the quiet or the stormy sea? What music is there, however artful, which can vie with the natural and changeful melodies of the resounding sea?

‘The sea is his, and he made it.’ Its beauty is of God. It possesses it, in richness, of its own; it borrows it from earth, and air, and heaven. The clouds lend it the various dyes of their wardrobe, and throw down upon it the broad masses of their shadows, as they go sailing and sweeping by. The rainbow laves in it its many colored feet. The sun loves to visit it, and the moon, and the glittering brotherhood of planets and stars; for they delight themselves in its beauty. The sunbeams return from it in showers of diamonds and glances of fire; the moonbeams find in it a pathway of silver, where they dance to and fro, with the breeze and the waves, through the livelong night. It has a light, too, of its own, a soft and sparkling light, rivalling the stars; and often does the ship which cuts its surface, leave streaming behind a milky way of dim and uncertain lustre, like that which is shining dimly above. It harmonizes in its forms and sounds both with the night and the day. It cheerfully reflects the light, and it unites solemnly with the darkness. It imparts sweetness to the music of men, and grandeur to the thunder of heaven. What landscape is so beautiful as

-----

p. 19

one upon the borders of the sea? The spirit of its loveliness is from the waters, where it dwells and rests, singing its spells, and scattering its charms on all the coast. What rocks and cliffs are so glorious as those which are washed by the chafing sea? What groves, and fields, and dwellings are so enchanting as those which stand by the reflecting sea?

If we could see the great ocean as it can be seen by no mortal eye, beholding at one view what we are now obliged to visit in detail and spot by spot; if we could, from a flight far higher than the sea eagle’s, and with a sight more keen and comprehensive than his, view the immense surface of the deep all spread out beneath us like a universal chart, what an infinite variety such a scene would display! Here a storm would be raging, the thunder bursting, the waters boiling, and rain and foam and fire all mingling together; and here, next to this scene of magnificent confusion, we should see the bright blue waves glittering in the sun, and while the brisk breezes flew over them, clapping their hands for very gladness—for they do clap their hands, and justify by the life, and almost individual animation which they exhibit, that remarkable figure of the Psalmist. Here, again, on this self same ocean, we should behold large tracts where there was neither tempest nor breeze, but a dead calm, breathless, noiseless, and, were it not for that swell of the sea which never rests,

-----

p. 20

motionless. Here we should see a cluster of green islands, set like jewels, in the midst of its bosom; and there we should see broad shoals and gray rocks, fretting the billows and threatening the mariner. ‘There go the ships,’ the white robed ships, some on this course, and others on the opposite one, some just approaching the shore, and some just leaving it; some in fleets, and others in solitude; some swinging lazily in a calm, and some driven and tossed, and perhaps overwhelmed by the storm; some for traffic, and some for state, and some in peace, and others, alas! in war. Let us follow one, and we should see it propelled by the steady wind of the tropics, and inhaling the almost visible odours which diffuse themselves around the spice islands of the East; let us observe the track of another, and we should behold it piercing the cold barriers of the North, struggling among hills and fields of ice, contending with Winter in his own everlasting dominion, striving to touch that unattained, solemn, hermit point of the globe, where ships may perhaps never visit, and where the foot of man, all daring and indefatigable as it is, may never tread. Nor are the ships of man the only travellers whom we shall perceive on this mighty map of the ocean. Flocks of sea birds are passing and repassing, diving for their food, or for pastime, migrating from shore to shore with unwearied wing and undeviating instinct, or wheeling

-----

p. 21

and swarming around the rocks which they make alive and vocal by their numbers and their clanging cries.

How various, how animated, how full of interest is the survey! We might behold such a scene, were we enabled to behold it, at almost any moment of time on the vast and varied ocean; and it would be a much more diversified and beautiful one; for I have spoken but of a few particulars, and of those but slightly. I have not spoken of the thousand forms in which the sea meets the shore, of the sands, and the cliffs, of the arches and grottos, of the cities and the solitudes, which occur in the beautiful irregularity of its outline; nor of the constant tides, nor the boiling whirlpools and eddies nor the currents and streams, which are dispersed throughout its surface. The variety of the sea, notwithstanding the uniformity of its substance, is ever changing and endless.

‘The sea is his, and he made it.’ And when he made it, he ordained that it should be the element and dwellingplace of multitudes of living beings, and the treasury of many riches. How populous and wealthy and bounteous are the depths of the sea! How many are the tribes which find in them abundant sustenance, and furnish abundant sustenance to man. The whale roams through the deep like its lord; but he is forced to surrender his vast bulk to the use of man. The lesser tribes of the finny race have each their peculiar habits

-----

p. 22

and haunts, but they are found out by the ingenuity of man, and turned to his own purposes. The line and the hook and the net are dropped and spread to delude them and bring them up from the watery chambers where they were roving in conscious security. How strange it is that the warm food which comes upon our tables, and the substances which furnish our streets and dwellings with cheerful light, should be drawn up from the cold and dark recesses of the sea.

We shall behold new wonders and riches when we investigate the seashore. We shall find both beauty for the eye and food for the body, in the varieties of shell fish, which adhere in myriads to the rocks, or form their close dark burrows in the sands. In some parts of the world we shall see those houses of stone, which the little coral insect rears up with patient industry from the bottom of the waters, till they grow into formidable rocks, and broad forests whose branches never wave, and whose leaves never fall. In other parts we shall see those ‘pale glistening pearls’ which adorn the crowns of princes, and are woven in the hair of beauty, extorted by the restless grasp of man from the hidden stores of ocean. And, spread round every coast, there are beds of flowers and thickets of plants, which the dew does not nourish, and which man has not sown, nor cultivated, nor reaped; but which seem to belong to the floods alone, and the denizens of the

-----

p. 23

floods, until they are thrown up by the surges, and we discover that even the dead spoils of the fields of ocean may fertilize and enrich the fields of earth. They have a life, and a nourishment, and an economy of their own, and we know little of them, except that they are there in their briny nurseries, reared up into luxuriance by what would kill, like a mortal poison, the plants of the land.

‘There, with its waving blade of green,

The sea-flag streams through the silent water,

And the crimson leaf of the dulse is seen

To blush like a banner bathed in slaughter.

‘There, with a light and easy motion,

The fan coral sweeps through the clear deep sea;

And the yellow and scarlet tufts of ocean

Are bending like corn on the upland lea.’

I have not told half of the riches of the sea. How can I count the countless, or describe as they ought to be described, those companies of living and lifeless things which fill the waters, and which it would take a volume barely to enumerate and name? But how can we give our minds in any degree to this subject; how can we reflect on a part only of the treasures of the seas; how can we lend but a few moments to the consideration of the majesty and beauty, the variety and the fulness of the ocean, without raising our regards in adoration to

-----

p. 24

the Almighty Creator, and exclaiming with one of the sublimest of poets, who felt nature like a poet, and whose divine strains ought to be familiar with us all, ‘O Lord, how manifold are thy works! in wisdom hast thou made them all; the earth is full of thy riches; so is this great and wide sea, wherein are things creeping innumerable, both small and great beasts. There go the ships; there is that leviathan whom thou hast made to play therein. These wait all upon thee, that thou mayst give them their meat in due season. That thou givest them they gather; thou openest thine hand, they are filled with good.’

We must not omit to consider the utility of the sea; its utility, I mean, not only as it furnishes a dwelling and sustenance to an infinite variety and number of inhabitants, and an important part of the support of man, but in its more general relations to the whole globe of the world. It cools the air for us in summer, and warms it in winter. It is probable that the very composition of the atmosphere is beneficially affected by combining with the particles which it takes up from the ocean; but, however this may be, there is little or no doubt, that were it not for the immense face of waters with which the atmosphere comes in contact, it would be hardly respirable for the dwellers on the earth. Then, again, it affords an easier, and, on the whole, perhaps a safer medium of communication and

-----

p. 25

conveyance between nation and nation, than can be found, for equal distances, on the land. It is also an effectual barrier between nations, preserving to a great degree the weak from invasion and the virtuous from contamination. In many other respects it is no doubt useful to the great whole, though in how many we are not qualified to judge. What we do see is abundant testimony of the wisdom and goodness of him who in the beginning ‘gathered the waters together unto one place.’

There is mystery in the sea. There is mystery in its depths. It is unfathomed, and perhaps unfathomable. Who can tell, who shall know, how near its pits run down to the central core of the world? Who can tell what wells, what fountains are there, to which the fountains of the earth are in comparison but drops? Who shall say whence the ocean derives those inexhaustible supplies of salt, which so impregnate its waters, that all the rivers of the earth, pouring into it from the time of the creation, have not been able to freshen them? What undescribed monsters, what unimaginable shapes, may be roving in the profoundest places of the sea, never seeking, and perhaps from their nature unable to seek, the upper waters, and expose themselves to the gaze of man! What glittering riches, what heaps of gold, what stores of gems, there must be scattered in lavish profusion on the ocean’s lowest bed! What

-----

p. 26

spoils from all climates, what works of art from all lands, have been ingulfed by the insatiable and reckless waves! Who shall go down to examine and reclaim this uncounted and idle wealth? who bears the keys of the deep?

And oh! yet more affecting to the heart and mysterious to the mind, what companies of human beings are locked up in that wide, weltering, unsearchable grave of the sea! Where are the bodies of those lost ones, over whom the melancholy waves alone have been chanting requiem? What shrouds were wrapped round the limbs of beauty, and of manhood, and of placid infancy, when they were laid on the dark floor of that secret tomb? Where are the bones, the relics of the brave and the fearful, the good and the bad, the parent, the child, the wife, the husband, the brother, and sister, and lover, which have been tossed and scattered and buried by the washing, wasting, wandering sea? The journeying winds may sigh, as year after year they pass over their beds. The solitary rain cloud may weep in darkness over the mingled remains which lie strewed in that unwonted cemetary. But who shall tell the bereaved to what spot their affections may cling? And where shall human tears be shed throughout that solemn sepulchre? It is mystery all. When shall it be resolved? Who shall find it out? Who, but he to whom the wildest waves listen reverently, and to whom all

-----

p. 27

nature bows; he who shall one day speak, and be heard in ocean’s profoundest caves; to whom the deep, even the lowest deep, shall give up all its dead, when the sun shall sicken, and the earth and the isles shall languish, and the heavens be rolled together like a scroll and there shall be ‘no more sea.’

—

-----

[p. 28]

NAPOLEON.

BY GRENVILLE MELLEN.

—

Napoleon, when in St Helena, Beheld a bust of his son, and wept.

—

Long on the Parian bust he gazed,

And his pallid lips moved not;

But when his deep cold eye he raised,

His glory was forgot;

And the heated tears came down like rain,

As the buried years swept back again—

He wept aloud!

He who had tearless rode the storm

Of human agony,

And with ambition wild and warm,

Sailed on a bloody sea,

He bent before the infant head,

And wept—as a mother weeps her dead!—

The pale and proud!

-----

p. 29

The roar of all the world had passed—

On a sounding rock alone,

An exile, to the earth he cast

His gathered glories down!

Yet dreamt he of his victor race,

Till, turning to that marble face,

His heart gave way;

And nature saw her time of power—

A conqueror in tears!

The mighty bowed before a flower,

In the chastisement of years!

What can this mystery control!—

The father comes, as man’s high soul

And hopes decay.

Alone before that chiselled brow,

His proudest victories

Flit by, like hated phantoms now,

And holier visions rise—

The empire of the heart unveils,

And lo! that crownless creature wails

His days of power.

The golden days whose suns went down,

As at the icy pole,

Lighting with dim but cold renown

-----

p. 30

The kingdom of the soul!

When all life’s charities were dead,

And each affection failed or fled

That withering hour!

Oh! had the monarch to the wind

His hope of conquest flung,

And to the victory of mind

Had his warrior footsteps rung,

What then were desert rocks and seas,

To one whom Destiny decrees

Such fadeless fame!

Oh! had the tyrant cast his crown

And jewels all away,

What though the pomp of life had flown,

And left a lowering day!

Then had thy speaking bust, brave boy!

Awoke with memories of joy

Thy fated name!

—

-----

From a Painting after Guido. Engraved by J. Cheney.

SIBYL.

Published by Carter & Hendee, Boston.

McKenzie Printr

-----

[p. 31]

THE SYBIL.

BY N. P. WILLIS.

—

INVOCATION.

Come to my call, sweet spirits! I am sick

Of the poor, even pulses of the world,

And I would yield me to some stirring spell

Till my sad heart sits lightlier. Ye have been

Dew to my life, bright ones! I have no joy

In my remembrance chronicled, unsung;

Never a gentle sorrow, nor a tear

Loosened from over-fulness, nor a prayer,

Nor a meek lesson of humility

Read in a violet’s beauty, nor a sigh,

Nor anything that hath a tie on love,

That is not linked with poetry.

My life

Hath had the seeming pleasantness of a child’s,

And I am bound up in the hearts of them

Who part the hair upon my brow, and pray

Daily for their fair girl; and I have drawn

Holy affections round me, and should find

-----

p. 32

Life but the gliding of a summer’s dream—

Yet I could sometimes die, its changeless pulse

Beateth so wearily, and there doth come

Over my brow a fever, and a thirst

Upon my spirit, difficult to allay,

And nature hath seemed dark to me, and eyes

From the dim kingdom of the night looked out

With a most troubled sadness; and when life

Became to me a wretchedness beneath

These sicknesses of spirit, I have found

Forgetfulness in poetry, and known

How like a blessed medicine it can steal

The pang of an impatient heart away.

Come at my bidding, then, ye spirit dreams!

And in my ears breathe music, and upon

My fancy pencil images of things

Holy and beautiful, and let me in,

As if I were a presence, to your rare

And unsubstantial world. I would put off

The memory of my nature till my love

Is from the earth estranged. I would forget

The heaviness of these delaying hours

Of waking, and go up with you awhile

Into the walks of air, and, like a cloud,

Give myself up unto the passing wind,

To float away on its invisible wings.

-----

[p. 33]

THE MANIAC.

BY S. G. GOODRICH.

—

On a tall cliff that overhung the deep,

A maniac stood. He heeded not the sweep

Of the swift gale that lashed the troubled main,

And spread with showery foam the watery plain.

His daring foot was on the dizzy line

That edged the rock impending o’er the brine;

His form was bent and leaning from the height,

Like the light gull whose wing is stretched for flight.

Far down beneath his feet the surges broke,

Above his head the pealing thunders spoke;

Around him flashed the lightning’s ruddy glare,

And rushing torrents swept along the air.

But nought he heeded, save a gallant sail

That on the sea was wrestling with the gale.

Far on the ocean’s billowy verge she hung,

And strove to shun the storm that landward swung.

With many a tack she turned her bending side

To the rude blast, and bravely stemmed the tide.

-----

p. 34

In vain! the bootless strife with fate is o’er—

And the doomed vessel nears the iron shore.

She seems a mighty bird whose wing is rent

By the red shaft from heaven’s fierce quiver sent.

Her mast is shivered and her helm is lashed,

Around her prow the kindled waves are dashed—

And as a vulture swooping in his might,

Toward the dark cliff she speeds her fearful flight.

She comes, she strikes! the trembling wave withdraws,

And the hushed elements a moment pause;

Then swelling dark and high above their prey,

The billows burst, and bear the wreck away!

One look to heaven the deep-wrapt maniac cast,

One low breathed murmur from his bosom passed;

‘God of the soul and sea! I read thy choice—

Told by the shipwreck and the whirlwind’s voice.

In this dread omen I can trace my doom,

And hear thee bid me seek an ocean-tomb.

Like the lost ship my weary mind hath striven

With the wild tempest o’er my spirit driven;

That strife is done—and the dim caverned sea

Of this wrecked bosom shall the mansion be.

Thou who canst bid the billows cease to roll,

Oh! smooth a pillow for my weary soul,

Watch o’er the pilgrim in his shadowy sleep

And send sweet dreams to light the sullen deep.’

-----

p. 35

Thus spoke the maniac while above he gazed

And his pale hands beseechingly he raised;

Then on the viewless wind he swiftly sprung,

And far below his senseless form was flung;

A thin white spray told where he met the wave,

And the piled surges form his fearful grave.

—

-----

[p. 36]

THE WOUNDED BIRD.

—

This wing no more can flight sustain,

Or I to distant groves would fly;

For less I heed the arrow’s pain

Than in my native wood to die.

Yet, be the struggle brief or long,

The victim’s moan they shall not hear;

Or it shall be a swan-like song,

Too sweet to mark his end so near.

Though scorn shall never watch the woes

It was its pastime thus to deal;

My last, faint flutter may disclose

The wound I can no more conceal.

Yet might it make the fowler weep

To see me fold my crimsoned wing

Upon a barb before too deep,

And hasten death to hide the sting.

P.

-----

[p. 37]

THE INDIAN FIGHTER.

BY THE AUTHOR OF ‘FRANCIS BERRIAN.’

—

That hermit hath gone to his last narrow cell,

And his bosom at length has forgotten to swell.

The couch, where he slept, is all crusted with mould,

And the fire on his hearth is extinguished and cold.

—

Whoever has travelled far, and seen many men, has seen much sorrow. That lonely man of singular habits, so well known, by those who navigate the Upper Mississippi, by the name of Indian Fighter, or the Hermit of Cap au Gris, has at length paid his last debt; and I am released from my promise, not to relate the passages of his life, until he was no more. I well know that the life of man is everywhere diversified with joy and wo; and that his story is but one of countless millions, varied only in the lights and shades. But it seemed right to me, to declare to the proud inhabitants of cities, that scenes of tragic interest, and incidents of harrowing agony, rise on the vision and pass away unrecorded in the desert. As I sojourned

-----

p. 38

on the prairies of Illinois, I experienced, for one night, the well known and ample hospitality of the hermit, and over his cheerful autumnal fire heard the following narrative of the more prominent events of his life.

‘The pride of life hath long since passed away from me. But it is due to the simplicity of fact, to declare, that my family in Britain was patrician, of no ignoble name, or stinted possessions. A hereditary lawsuit deprived us of all but the mere wreck of our fortunes. We came over the seas, to escape from the scene of our pride and humiliation. We crossed the western mountains. We were borne down the forests of the beautiful Ohio. We ascended the majestic father of waters, and debarked on the devious and secluded Macoupin, which, after winding through the central woods and prairies of Illinois, pays its tribute to the Upper Mississippi, some leagues above the mouth of the Missouri.

‘With us emigrated a band of backwoodsmen, who sought their homes on these fair and untrodden plains. As friends knit by the ties of common pursuits, and the strong bond of intending to be fellow dwellers in the desert, we selected contiguous farms on the open grass plains; and our cabins rose under the peccans [sic] and sugar maples, that formed a skirt of deep and beautiful forest on the banks of the stream. We were fresh

-----

p. 39

from the fastidious creations of luxury and art. I well remember the day when our tents were first pitched in the wild. Here all was fresh nature, as in our forsaken home all had been marked with the labor of men. The sky was beautifully blue and cloudless; and the mild south gently rustled the trees, as it bore fragrance in soft whispers along the flowering wilderness. The huge, straight trees were all moss-covered; and their gray trunks rose proudly, like columns. The starting hares, and deers, and the wild denizens of the woods bounded away from our path. Eagles and carrion vultures soared above our heads. Birds with brilliant plumage of red, green, and gold, sang among the branches. The countless millions of water dwellers, awakened from the long sleep of winter, mingled their cries in the surrounding waters. We added to this promiscuous hymn of nature the clarion echoes of our bugles, the baying of our dogs, all the glad domestic sounds of animals that have joined partnership with man, the hearty blows of the woodcutter’s axe, the crash of falling trees, and the reckless wood notes of the first songs which these solitudes had heard from the creation. I look back upon these pleasant, and too fond remembrances, as a green island in the illimitable darkness of the past.

‘We consecrated our cabin in this forest with the affecting and tender name of home. I have seen many

-----

p. 40

a spot since, where nature is beautiful in privacy and seclusion, as it should seem, for her own solitary joy; but none more like Eden than this. I had scarcely lived twenty years. I had seen the richly dressed and haughty fair of my native country and of American cities, as an equal, and all with the same indifference. It may be that the heart has more tender sentiments, the eye keener perceptions, and the imagination more vivid and varied combinations, in places like these, than amidst the palling and commonplace associations of art. Little had I dreamed that in these wild forests I was to see a vision of loveliness, which will forever remained impressed upon my memory and my heart, like the stamp of the seal upon wax. Here is the image of the loved one, I hope innocently worn along with that of my Saviour. I pass my eye from one to the other; and while I remember that they are both in heaven, I long to rejoin them.’

His voice failed for a moment; and he took from his bosom, where it hung with a crucifix, on which, engraven on a gem, was the head of a Jesus, a miniature of a beautiful girl, with raven locks, and radiant eyes of piercing blackness. It showed a countenance of uncommon loveliness even to me, who saw with impartial view. But the eye of a lover discovers perfection where less entranced vision sees

-----

p. 41

only common beauty. As I intensely viewed the miniature in different lights, he proceeded, in the luxuriant amplification of a lover’s poetry, to paint his beloved with a pencil dipped in sunbeams. The ambrosial curls, the divine expression of a melting eye, the lily and the rose in her cheek, the snowy neck, the majestic form, in short, the usual illustrations of that vocabulary were all put in requisition.

‘She, too,’ he resumed, replacing the miniature in his bosom, ‘before she had seen sixteen summers, had seen reverses; and her piercing eye sometimes swam in a languor, which told a tale of sorrow. Her father had ventured all on the seas; and his wealth had been merged in the fickle element. His proud spirit, like mine, brooked not the affected pity of those who had shared in the hospitality of his better days. He sought repose in the same forests, and had selected his home on the same stream a few leagues above. In passing near our cabin, his horse, affrighted by the starting of a hare from his path, had thrown him. I found him, bore him home, and nursed him, during his lameness, till he was able to return to his own house. Next time we saw him, he brought his lovely daughter with him on a visit to our settlement. I no longer complained of the tedium of slumbering affections, or spoke in derision of the mock torments of love.

-----

p. 42

‘The time of her visit was a sweet April evening; and the place an extensive sugar camp, near our cluster of cabins. The greater portion of our settlement were gathered round the caldrons [sic] and the blazing fires in that pleasant valley. The sugar maple poured its rich syrup abundantly; and the tree itself, the fairest of the American forest, had begun to start the germs of its leaves beneath its brilliant red flowers. The fresh air told that the snow had not yet all melted from the higher hills. But violets, columbines, the white clover, the cornel, and red bud already mingled their fragrance in the evening breeze. A requiem to departing day was lulling the song birds to rest among their branches. A number of black servants, engaged in the work, sang, in the strain of their spicy native groves, songs, at once gay and plaintive, which breathed remembrances of the Lote and the Palm. Steaming above the bright fires arose the fragrance of the forming crystals. The aged parents sat under the trees, and told their feats of hunting buffaloes and bears, and their still sterner contests with the Indians. The young men and their elected maidens were grouped apart. A fat and joyous black, as laughing and as reckless as though he had neither heard nor known the import of the word slave, scraped his violin. At the note the scattered groups left their satisfying privacy for the more exciting sport of the dance. The Africans, meanwhile, enacted

-----

p. 43

their own under plot of still more boisterous gladness; and, when weary with laughter, sipped the syrup, and, imitating the phrase of the adjacent dancers, talked of their dusky loves as still sweeter than the forest nectar.

‘It was at such a time and place that the father and Emma dismounted from their horses and joined us. It was, as if Diana had descended amidst the rustic assemblage. I no longer had indistinct visions of grace, and loveliness, and dignity, which all stood embodied before me. The time and the place added their charmed influence to the impression. The father named me to his daughter as one to whom he owed a debt of grateful obligation. At her home the maple was not found; and this scene, and the process of preparing the sugar, had for her all the charm of novelty. She seemed no ways disinclined to make the circuit of the camp with me, nor to repose herself on a rustic bench at a spring fountain, whence the whole gay scene was surveyed below, and which was beautifully illumined by the hundred bright fires. Her reserve wore away with mine; and I became bold, as she turned her melting eye upon me, as if to inquire, why a being as unlike the rest as herself, had been cast in these woods. I talked of the charming country, and of the unlimited selection in these fertile solitudes. I spoke of the peace of those who are far from the corroding passions

-----

p. 44

and the venal motives of crowded cities, and who live in guileless peace, content, and privacy; and, I added, that the poet’s song, in the days of primeval innocence, had peopled such scenes with gods and nymphs; but that I had not dreamed to find, as I now did, the fable true in these iron days. A smile slightly ironical gave me no omens of displeasure. We named over our stores of books; and in the course of this delightful evening she incidentally expressed the hope that our fathers might be acquainted. The song and the dance and our fathers’ colloquy and ours ceased not until the moon in the centre of the concave told us, that it was the noon of night; and yet much remained for us both to say.

‘Her father came for her, complaining, in the usual phrase, of the unperceived lapse of the hours. They mounted, and rode towards their home. I followed them with my eyes and my thoughts, as the yet unabated and boisterous mirth around rung upon my ear. The tempest of war had begun to rage along our immense line of frontier; and the fierce and ruthless northern savages were abroad among the commencing settlers of the Illinois plains. We began to hear of their desolations of fire and blood. I neither affirm nor deny the wisdom of believing in presentiment in the case of others. It may be I followed the leading of a new train of thoughts; but it seemed to me as if

-----

p. 45

a mysterious intimation warned me to follow in their course. I moved over the hills until our fires had faded upon my eye, and the mirth around them upon my ear. One height drew me on to another, until I heard a sharp and piercing scream, preceded by a rifle shot, in a thicket but a little way before me. An instant brought me to the place. The father lay on the ground, apparently lifeless, and covered with his blood. A half-suppressed groan, as if one flying away among the fallen trees, directed me to the daughter. She, too, was on the earth; but whether in faintness or death, appeared not; though, reclined in her white dress, my dark thoughts viewed her as lying in her shroud. In springing to reach her, I stumbled over a fallen tree. It providentially saved me from the unerring aim of an Indian hatchet, which gleamed past the point, to which I should otherwise have advanced. The sender instantly after grasped me in deadly strife. Then first I knew by experience the fierce encounter of the red man. Providence or love endowed me with more than mortal powers. While I felt in the tremendous clutch of my adversary, as exerting the weak efforts of man against the brute and irresistible powers of nature, I had, I scarcely know how, inflicted such a wound, that I felt his spasmodic grasp relax. His arms sunk away nerveless; and the sternness of disappointed vengeance was sealed upon his grim brow in death.

-----

p. 46

‘I need not prolong my tale. Water from a neighbouring spring restored Emma. She had fled unharmed, and fallen in faintness and terror. Her father had been wounded, but not severely, by a rifle shot. He was removed to my father’s cabin; and nursed, I need not say, with tenderness. While a firm friendship grew up between the fathers, a compact of another sort had been unalterably ratified between their children. There was no glade, spring source, or cool and sequestered bower of the broad-leaved grape, that had not been consecrated by the repetition of our vows, and our words of love. The days fled, and we counted not how fast; for the sun, moon, stars, and seasons were not our remembrancers. Alas! the memory of these halcyon days alone remains to me; but even the memory is pleasant. It is like a calm and sweet dream in a feverish night of pain.

‘The time of our union was fixed. Our parents would not separate until it had taken place. Ample provision had been made for our commencing a farming establishment in rustic abundance and comfort. Earth can furnish no happier anticipations than were ours.

‘A savage that we had deemed friendly, and who often brought us venison for sale, came in one evening, when a number of our neighbours were paying us a social visit. He begged my father to send some one to help him bring in a deer, which, he said, he had

-----

p. 47

killed near the house. The greater number of the men, and I among them, improvidently set forth to see the game. An ambush of hostile Indians rose between them and the house. The yells of the savages, the dying groans of our neighbours, the sharp reports of the rifles, all ring in my ears as I think of the past. I was stunned and struck down, remote from the rest, with a rifle blow. The fathers and mothers, the brothers and sisters, the husbands and wives fell together. Savage knives spilled the blood of the young infants. They exerted themselves even to kill our house dogs. To render the ruin complete, conflagration glared upon their murders. With horrid dexterity, they composed a pyramidal pile of bodies; the longer laid at the base, the shorter forming another tier, and the little infants, lying in their innocent blood, crowned the pile. By this pile they held their infernal orgies, dancing and yelling, as they circled round it, by the glare of the burning buildings. I should have made one, had they found me. I remained awhile insensible at a distance among the brush; and awoke to consciousness with this shocking scene in full view, though it was my fortune not to be myself discovered.

‘In the midst of their horrid rites of blood and drunkenness, the clarion notes of the rangers’ bugles awakened the night echoes. The murderous foe cowed and fled, like wolves from the sheepfold.

-----

p. 48

Had it been heard an hour before, I had not passed from hope to despair; and many a brave heart had palpitated with the joy of welcome, which would now beat no more. The rangers soon came up in measured gallop, and, clad in steel, alighted to survey the work of death. I called them to my aid. They carried me to a cabin which the savages had spared; and I speedily recovered of my bruises. Revenge burned at my bosom, and for that alone I wished to live. Besides, the body of Emma had not been found among the dead. Might not the loved and forlorn orphan be a captive to these ruthless invaders? To seek for her, and to measure back to the murderers the cup of retaliation, these were motives for which to cherish life. All uncertainty touching Emma’s fate, was soon dispelled. A single captive, with her, sole survivors of the massacre of my father’s house, escaped them, rejoined our settlement, and reported, that they were carrying the lovely captive to Rock Fort, near Peonia of the Illinois.

‘The rangers had gone on their ordered destination, in another direction. But, stimulated by the sympathy of common feelings, and urged by my despair, a few gallant friends from the vicinity joined me in pursuit of the captive. They were brave and determined spirits, who knew how to find a home in the forest, to whom rivers and forests, and prairies and distance, and danger and death were familiar objects. They

-----

p. 49

were men of robust body and unconquerable mind. We mounted our horses, heedless of provisions, as long as we had powder and lead, and as long as the prairies and the forests alike afforded food for our horses. We bounded away through the wood, stream, prairie, and over hill and dale. On the third night of our march we saw the watch fires of our foe gleaming afar through the forests. So far away from the scene of their murders without pursuit, they now reposed in reckless riot. Gorged with food, most of them slept in drunkenness. One trusty sentinel slept not; and his dismal guttural song occasionally chimed in with the hoot of the owls, the long dismal cry of the wolves, and the distant crash of trees, falling in the forests under the weight of time.

‘I felt that my motives impelled me to confront the first dangers; and they detached me to reconnoitre, or, if I chose, to enter the camp in secret. I almost suppressed my breath, the beatings of my heart I could not suppress, as, panther-like, I crept upon the foe. The tall, grim sentinel, with half blinking eyes, nodded erect over a decaying fire. A fallen tree interposed on his f[l]ank, as a screen, and I crept undiscovered by him. Unheeded, as I crawled, I surveyed many a brawny warrior in deep sleep; and one, as I passed near him, half started up, and commenced a dozing note of his habitual “Cheowanna! ha! ha!” and sunk back to his visions. Providence, that watches over innocence,

-----

p. 50

guided me to the very tent where Emma lay, feeding upon her sleepless tears. A start of joy marked her instant recognition. “Hush! A word is death. Follow me. We are free, or fall together!” I waited in breathless impatience. In sounds inaudible by any but a lover’s ear, she whispered, “I am bound.” I cut the vile bonds from her swollen and tender limbs. I felt at my heart the full and confiding pressure of her pledged hand. We stole away, as noiseless as the footstep of time. Our devious course was often changed by seeing a gigantic body, first in this direction, and then in that. More than one turned in his sleep, as we passed, with a half waking spasm, and settled back with a long drawn sigh to his repose again. The warrior sentinel seemed to have caught in his ear the rustle of our feet among the leaves; for he raised himself fully erect, and cast a keen and searching glance on every side. We sunk unmarked behind a briar tangle. Our hearts palpitated equally with love and terror during this suspense of horror. The grim Argus, having scrutinized the whole scene with a detail of survey, stirred his fire, passed his dusky form twice around it, uttered in his most lugubrious tones, “Cheowanna! ha! ha!” and, as if ashamed of his fears, seemed to court his former dozing apathy.

‘This dreadful suspense elapsed, we fled; and I safely brought back the captive orphan to my friends.

-----

p. 51

We saw most clearly that the foe was too numerous for prudent attack. We whispered a moment in earnest debate. Having secured the chief object of pursuit, we concluded to return with all possible speed to our settlement. We commenced our march by the uncertain light of the moon, now dimmed by clouds and mists. Morning dawned upon our forest march in crimson splendor and dewy freshness. The glad sounds of matin music showed that every living thing rejoiced in the renovated day but ourselves. We would have chosen the sheltering darkness that was the scourge of Egypt; for, from the hills behind us, the Indian yell of pursuit was heard. Behind us was this loud and appalling war song of the foe; before us a prairie, gay with flowers, dripping and sparkling in the freshness of morning dew, but measureless to vision, and offering only the unsheltered nakedness of a level plain.

‘To fight, retreat, or seek shelter, were our only alternatives. The foe outnumbered us ten to one. Their horses were fresh; ours fatigued. We were unwilling that the rescued orphan should sustain the same chance from their rifles as ourselves. One of those immense elliptical, concave basins, so common on the verge of the western prairies, offered itself before us. The general voice was to descend the basin, take down our horses, and, if we might, lie there concealed until the storm of pursuit should be past. If the foe had

-----

p. 52

not tracked us, our chances were good. The basin was a hundred feet in perpendicular depth; and the descent so prone, that our horses slid from the summit to the base. Briars and thorns and bushes and small shrubs sheltered the rim as a kind of hedge. At the base a cool spring trickled across the limestone floor.

‘Here we stood in breathless suspense, while Emma clung fast to my side. Alas! we soon heard the measured trample of their horses at hand; and, as if to preclude all chances of concealment, our horses, scenting theirs, neighed vehemently, and were instantly answered by theirs. Our basin was surrounded in a moment. The rifle’s sharp clang was heard, again and again, followed by the heavy sigh of my falling comrades; while our return fire upon those who stood high above, and showed only their heads at the moment of discharge, took little effect. Emboldened by impunity, and impatient at the slowness of their work, the foe soon came howling down the basin. Then we fought at bay, and with desperation; and the blood of more than one of their number mingled with ours. Emma fell on my bosom. “Henry,” said she, ‘we die together.” Stout frames, and noble minds, and fearless hands availed nothing against numbers. Darkness came over my own eyes; and the last sensation of a heavy and iron sleep,

-----

p. 53

was, that our released spirits were making the last journey together.

‘But life returned to me, and brought with it bitter and distinct consciousness, and rayless despair. The morning sun had just emerged from the mists when we entered this basin. It was now burning noon. I lay on the stone floor. The pale, cold face of Emma was near me. Her eye, lately so piercing, was fixed and glassy. I was bound in various points by thongs, which a giant could not have broken. I struggled madly with them, until I was exhausted, and nature would go no further. Then I cried to Heaven from the depths, and called aloud on God for mercy. When I paused in the intervals of my groans, what a spectacle! There were my companions, lying as they fell. My brain began to madden. I strove to dash my head on the stone floor. Bright, broad gleams of light, in all the colors of the prism, filled the heavens in my view, and I fondly hoped that my last hour had come. But I was not permitted thus to lay down my loathed life.

‘The sun seemed, for a whole age, to remain suspended high in the heavens only to concentre his radiance on my head. But after the scorching of theat long period, the burning orb declined. I was in darkness, wet with the chill dews of night, and constantly enduring the benumbing torture of my cords. First I heard the hooting of owls. The panther’s harsh

-----

p. 54

scream next grated on my ear. The sharp bark and the hungry howl of the wolves commenced, and still drew nearer. I soon heard their menacing growl, and their stealthy and cat-like tread. Immediately after a whole troop, emboldened by numbers, rushed down the den, licking their greedy jaws, as they fell at once upon their horrid feast. The bodies were torn, and in their rabid eagerness, they often turned their rage upon each other. Could they have instantly destroyed my own life, I had been content. But, when I saw them tearing the form of my beloved, all my associations with life arose; and I unconsciously raised such a cry of horror, as drove the satiated and coward prowlers in rapid retreat from the den.

‘The morn returned. The hot sun once more illumined the summit of the basin. Corruption had commenced its appropriate work; and a new evil, more insupportable than all the rest, crowned my miseries. I burned with the mad thirst of fever, and my mouth and throat were as parchment. Then I knew the truth of all that I had heard of the agony of thirst. Mere physical thirst expelled all horrors of the mind, and reigned sole object of my thoughts. Drink! Give me drink! I cried, till I heard the wild echoes calling for drink. I had no conception of any misery but thirst, or of any joy in earth or heaven, but to quaff water forever from a cool spring.

-----

p. 55

‘Then I felt that time is a relation of the mind, and the creation of thought. I looked up at the sun. Roll on, I cried in my despair; roll on, and bring me death. But it seemed as though the voice that suspended his course in Ajalon had renewed the mandate. Worn down and exhausted, I slept, as I knew by a waking start, that broke off a dream that myself and my beloved had passed our mortal agonies and were safe landed in heaven. The cool evening was drawing on, convincing me, that in joy or sorrow, time never stands still. I had long seen the carrion vultures wheeling their droning flight above the basin, allured by the scent of carnage. The effluvia now directed them to their mark. They settled down by hundreds.

‘But God, who is rich in mercy, heard my cry in the bottom of this deep basin. The corps of mounted rangers was scouring the prairie in search of the bodies of their friends. Their practised eyes were directed in a moment, by the wheeling circles of these birds of evil omen. They found me; and in the madness of my thirst, I struggled with them in wrath, to be allowed to quaff my fill, and drink death at the spring. But by kindly violence they held me back. Some washed my swollen limbs, while others with manly tears committed decently to the earth the mangled remains of my friends.

‘All my purposes and affections were now concentered in the insatiate desire of retaliation and vengeance. At

-----

p. 56

the head of a volunteer corps of rangers, I vowed to the shade of Emma, that I would expiate her murder by copious libations of Indian blood. I faithfully redeemed my pledge. When a daring assault was to be made on one of their villages, or a body of their warriors, I was the first in attack, and the last to spare. My companions saw that I took no counsel from distance, toil, exposure, or danger. My only inquiry was, where is the foe? My corps emulated my example; and many a burning village testified to the deluded miscreants that we knew how to retaliate. So terrible had my name become to them, that I bore in their language an appellation which imports Indian Fighter.

‘At length we met the same band that destroyed my father’s family and Emma. they retreated, after a short fight, to the same basin where she fell. It was filled with the high grass of autumn. We sent down flames among them, and drove them howling upon the plain. We destroyed many of them there. The remnant fled before us to their lair, their summer residence near the Illinois. Here were their wives and children, and the mounds that contained the bones of their forefathers. Here they turned and stood a bay. Why should I recal [sic] these scenes of vengeance and blood? their warriors agreed to kill their women and children, and then despatch each other. We heard the aged warriors singing the death song, as the work

-----

p. 57

of destruction went on. Our rangers were affected, and the reports of their rifles ceased. All had fallen but the leader of the band. He fired the village, and came forth. “Indian Fighter,” he said to me, “I killed thy father and mother. I killed the maiden of thy love. If thou art indeed a warrior, and a warrior’s son, seek thy revenge now.” Nor was I one to refuse that invitation. We struggled long for mastery, for life and death. These scars remain, as durable memorials of that strife. But as I was weak with loss of blood, I shouted Emma! and my arm was renerved. He rolled on the grass, and I saw, not without a strange feeling of respect, the look of defiance and denial of triumph fixed on his stern brow, after his spirit had passed.

‘Peace has revisited these plains any years past; and it is not long since I made a pilgrimage to the ruins of the Indian village. I should say to thee, stranger, that I trust I have long since become a Christian. Anger, revenge, despair are alike merged in my immortal hopes, and the new tempers of a better mind. I stand amazed at myself, and ask, is this quiet and forgiving bosom the same, where such a whirlwind of vengeance and wrath so lately raged? I shed tears of pity and forgiveness over these affecting ruins. There were the scathed peach and plum trees. There were the dilapidated remains of the few cabins that had escaped the fire. There were the clumps of hazel bushes

-----

p. 58

covered with the wild hop. There were patches of the green velvet sward of blue grass, indicating that human habitancy had introduced it among the wild grass of the prairies. I remembered to have seen this sward covered with the business and bustle of life. I remembered the bench at the head of the village, where I had beheld the aged council chiefs smoking their calumets in silent gravity. Their bones were now bleaching around me. In their sculls [sic] the ground rattlesnake had gathered up his coil, and waited for his prey. But the robin redbreast and the purple cardinal, birds that love the shorn sward of blue grass, picked their seeds upon it, and now and then started a few mellow notes, as if singing the dirge of the dead.

‘That whole race is wasting away about me, like the ice in the vernal brooks. I shall soon be with them. But, stranger, when thou goest thy way, say to those that come after me, that it is wise, as well as christian, to stay the storm of wrath, and leave vengeance to Him, who operateth by the silent and irresistible hand of time, and will soon subdue all our enemies under our feet.’

—

-----

[p. 59]

TO A BRIDE.

BY JOHN W. STEBBINS.

—

Farewell! that seal is set,

In life unbroken;

Thou hast with the heartless stranger met—

With the quivering lip, the eyelid wet,

And blessing spoken—

In the holy scene that haunts me yet.

Farewell! for thou art now

Enshrined forever;

With the bridal chaplet round thy brow,

And thy spirit holier for the vow,

That breaks not ever,

To which thy soul must hopeless bow.

For thee my lonely heart

With passions’ sorrow

Will wither as thy guileless steps depart,

And oft the heavy tear will start,

When on the morrow

Thou ’rt gone, my life-star as thou art!

-----

p. 60

Yet is thine image one,

That long will linger

In Memory’s temple, like a melting tone

Of music from a spring bird gone,

Till Death’s dark finger

Hath written that my hour is run.

My love will to thee cling,

Like thought in morning

Around a vision that hath taken wing

From sleep, or as to flowers of spring,

The bower adorning,

That have been ta’en away while blossoming.

Farewell! I keep my sight

Where thou art fleeting,

And with a feeling of sad delight,

While darkens around me despair’s deep night,

View thee retreating,

As if an angel was there in flight.

—

-----

R. Westall. O. Pelton.

INNOCENCE.

Published by S. G. Goodrich & Co. Boston.

-----

[p. 61]

INNOCENCE.

BY GRENVILLE MELLEN.

—

‘The pure in heart.’

—

Emblem of purest light on earth!

In whom the beautiful has birth,

That with a silent power commands

The stern and sinful of all lands;

Type of the sainted and divine!

That first on Eden’s bowers did shine

With the young morning of that day

So soon to pass in clouds away!

Sweet purity and love!—sleep on—

Not yet, not yet has glory from the dim earth gone!

Sleep mid thy forest leaves, fair boy—

The heavens hang over thee in joy,

And through thy shadowy solitude

Steals glaring by the horrid brood

Whose roar has startled the lone night,

Turning the dream-flushed slumberer white,

-----

p. 62

Now passing onward as in fear

Of youth so bright and brow so clear,

Laid in its wondrous beauty there,

Under the waving woods and dewy scented air!

Sleep ’neath thy whispering canopy—

Thy infant look has hallowed thee,

And thy untented head reposes

Mid noise of brooks and breath of roses,

’Neath desert crags with garlands gray,

Where wild birds wing their glancing way,

Secure, as if in guarded dome

Had been thy pillow and thy home,

As though a hundred heads were bent

Intense, o’er thee, less lovely and less innocent!

So go the beautiful in heart,

From all the troubled world apart,

And mid the wild flowers and the voice

That make life’s wilderness rejoice—

All bloom and music!—they lie down

With time’s most enviable crown!

Kind spirits glance about their way,

And guard and glad each dreamy day,

Until the quiet and the pure

Pass to that better world whose glories shall endure.

-----

[p. 63]

THE HEIGHT OF IMPUDENCE.

BY JAMES ISAACS.

—

Mr A. Flint was a clerk in one of the public institutions in the city of New York. He received a modest salary for his services, which enabled him to support in comfort, and with unambitious propriety, a wife and a very small family. It is not at present necessary to be more explicit as to his circumstances. He was a good man; that is to say, good enough, according to the moral barometer of his times and his topical latitude and longitude. But he was a man of timid disposition; and, though not troubled himself with thick coming fancies, was apt to be troubled by those of other people, whether they were traditional or inspired. Mr Flint had no great taste for encountering belligerent flesh and blood in the day time; and of ghosts in the night time he had a mortal abhorrence.

Now he was returning once, on a winter afternoon, after his daily labors, to his dwelling in one of the streets in the upper part of the town, which cross the Bowery Lane, reflecting, probably, on the small

-----

p. 64

concerns comprehended in the small routine of his own operations and associations. I have no right to thrust a candle into his encephalic machinery, or to mention any other of his cogitations than the following. He reflected that his wife had gone to drink tea with her neighbour, Mistress Dobbs, and had taken the three small children and infant with her, and that he had promised to call for them; and, as he felt already very much fatigued indeed, he sorrowed that the balance of his daily labor was not yet stricken.

But, as may be inferred, he was an obedient husband, and easily pacified with a good reason, or no reason at all, when he got it from his wife. He grinned and bore the minor trials of this life with creditable and enviable resignation. One other domestic anticipation, at the point of time from which I start, made him uneasy. He was apprehensive that his solitary domestic, with her usual Gallio-like contempt of orders, had availed herself of the absence of her mistress and her Cupids, to go a-visiting likewise; thus leaving the house empty of all live stock, save the cat and her customers.

The day had been cloudy; and when our friend arrived at his own door, it was, as they say, pretty much dark. He knocked; but no one appeared, nor did he hear any stirring within. The house was of humble pretensions, having but one entrance in front. The door of this, with considerate precaution, was

-----

p. 65

always fastened on the inside; but, as dead silence succeeded to the reverberations of a second knock, our friend thought he might as well, by way of experiment, try the handle before he went to the neighbouring grocery store, where the key was usually left on such emergences. [sic] Much to his surprise, this piece of chironomy operated as an open sesame; or, in plainer English, the door opened, and he stood in his own entry. Internally bestowing a malison on the untrustworthy wench, who had left the house thus desolate and liable to invasion, and, with a slight flutter of trepidation, Mr Flint made his way through the dark but familiar passage, hoping to find in his back parlour, sparks enough among the ashes to light a candle with.

Hastily entering, and unconsciously closing the door behind him, he was thrown into an unequivocal paroxysm of terror. A far better fire than had ever gladdened it under Mr Flint’s administration, was blazing on the hearth. Two spermaceti candles on the mantlepiece, long kept for ornament and not for use, were dispensing their radiance beautifully. There was light, and too much of it; for, right in front of the fire, with his back to Flint, sat the strangest figure his eyes had ever beheld. It was sitting on a pillow, which must have appertained to the family bed, and have been brought from a room above; and the coup d’œil our friend took, before the ague of his fear came upon

-----

p. 66

him, revealed to him the astounding fact, that this phantom was using for a spit-box the curiously painted China jar, which his wife’s aunt had left her in her will, and which had been immemorially, that is to say, for seven years, the pride of Mrs Flint’s mantlepiece. That mantlepiece was now singularly adorned with two very muddy old overshoes, one hanging on each side from a branch of a brass ornament; while an old greasy hat, with a brim whose circumference was as large as that of a corn basket, depended between them from the nail that supported the picture of Flint’s grandfather. Other desecrations seemed to have taken place; but the visible objects in his back parlour were presented to our friend, just as those on the road are to a traveller, in a dark night, by a flash of lighting. The presence of the representation of a man before the fire, palsied his physical energies, and he was completely terrified. His immediate impulse was to make his exit, more rapidly than he had made his entrance, and to call for help from his neighbours. But, either from the disordered state of his nerves, or from some other cause which is unknown, the knob of the lock was not so successfully tractable as its brother at the street door had been, and our friend’s dalliance with it was ineffectual;

‘For his trembling hand

Refused to aid his heavy heart’s demand.’

-----

p. 67

But, heavens and earth! what were his feelings, when the Eidolon before the fire slowly turned round, and fixed him with its calm, cold, fascinating gaze! He did not swoon; but, as the clammy moisture gushed from his forehead, stood, upheld by the energy of his own terror, which was so strong, that if his organs of speech could have executed a monosyllable, his paralysed will was not able to dictate it. I hold it to be indecorous to go further into the anatomy of the passion of fear.

‘Amaziah,’ said the Image, ‘sit down. I have something to say to thee.’