The Token and Atlantic Souvenir, edited by Samuel Griswold Goodrich (Boston: Gray & Bowen, 1830)

-----

[presentation page]

Drawn by G. Hervey ANA Engraved by E. Gaulladet.

-----

[frontispiece]

Painted by Newton. Engraved by Danforth.

ISABEL.

Published by Gray & Bowen, Boston.

-----

[“fancy title page”; engraved title page]

-----

[printed title page]

CHRISTMAS AND NEW YEAR’S PRESENT.

—

EDITED BY S. G. GOODRICH.

—

‘Then take my flower, and let its leaves

Beside thy heart be cherished near,

While that confiding heart receives

The thought it whispers to thine ear.’

BOSTON.

PUBLISHED BY GRAY AND BOWEN.

—

MDCCCXXXI.

-----

[copyright page]

DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS, TO WIT:

District Clerk’s Office.

Be it remembered, that on the tenth day of August, A. D. 1830, in the fiftyfifth year of the Independence of the United States of America, S. G. Goodrich, of the said district, has deposited in this office the title of a book, the right whereof he claims as proprietor, in the words following, to wit:—

‘The Token, a Christmas and New Year’s Present. Edited by S. G. Goodrich.

“Then take my flower, and let its leaves

Beside thy heart be cherished near,

While that confiding heart receives

The thought it whispers to thine ear.” ’

In conformity to the act of Congress of the United States, entitled ‘An act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies during the times therein mentioned;’ and also to an act, entitled ‘An act supplementary to an act, entitled “An act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies during the times therein mentioned; and extending the benefits thereof to the arts of designing, engraving, and etching historical and other prints” ’

JNO. W[.] DAVIS,

Clerk of the District of Massachusetts.

-----

[p. iii]

PREFACE.

—

In coming a fourth time with our sober ANNUAL before the world, we need offer little, beside thanks to the public and to our friends, for the ample aid and favor, they have hitherto bestowed upon us.

We have already expressed our intention to make the Token strictly national, and to depend entirely upon the resources of our country for the engravings, and the literary contents of the work. We yet see no cause to regret, or change this design, and as in the present volume, so in the future ones, we propose to adhere to it.

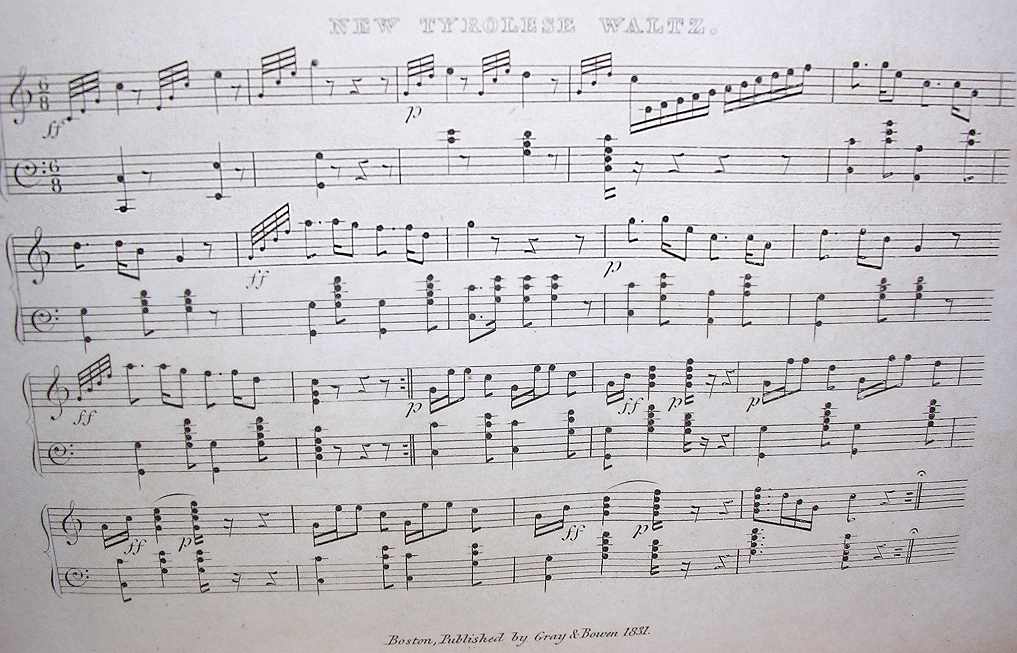

We have the pleasure of giving in the present work an engraving from our countryman, M. J. Danforth, who has so much distinguished himself in London, within the last two years. We have also one engraving from a fine picture by Cole, for which we owe particular thanks to D. Wadsworth, Esq., of Hartford, to whom the picture belongs, and who politely gave us permission to have it

-----

p. iv [printed as vi]

copied. For the piece of music inserted in the volume, we are indebted to Dr Lieber, who received it recently from Germany, where it was among the new favorites of the musical world.

As to the future, we need only add, that we have made arrangements to prosecute our work with additional zeal, and we hope with additional satisfaction to the public. If we mistake not, the present volume will be found to possess higher claims than any of its predecessors, to public approbation, and it will be our aim, every succeeding year, to surpass what has gone before.

To our contributors we owe many thanks, and some apologies. If any of them have had reason to expect the insertion of pieces which are not to be found in the volume, we beg them to impute what may seem neglect, to simple necessity. We are too deeply sensible of our dependence upon them, willingly to give them just cause of complaint. We may be permitted to say that most of the embarrassment we feel, in the editorial department of our work, arises from the lateness of the period at which the articles are received, and from the undue length to which many of them extend. We need but intimate these things, and hope our friends will hereafter keep them in mind.

-----

p. 5

EMBELLISHMENTS.

—

1. Presentation Plate—designed for Gray and Bowen, by G. Harvey, and engraved by E. Gallaudet.

2. Titlepage—The Ornamental Part designed for Gray and Bowen, by G. Harvey, and engraved by V. Balch. The Figures engraved by E. Gallaudet, after Sir Thomas Lawrence … 1

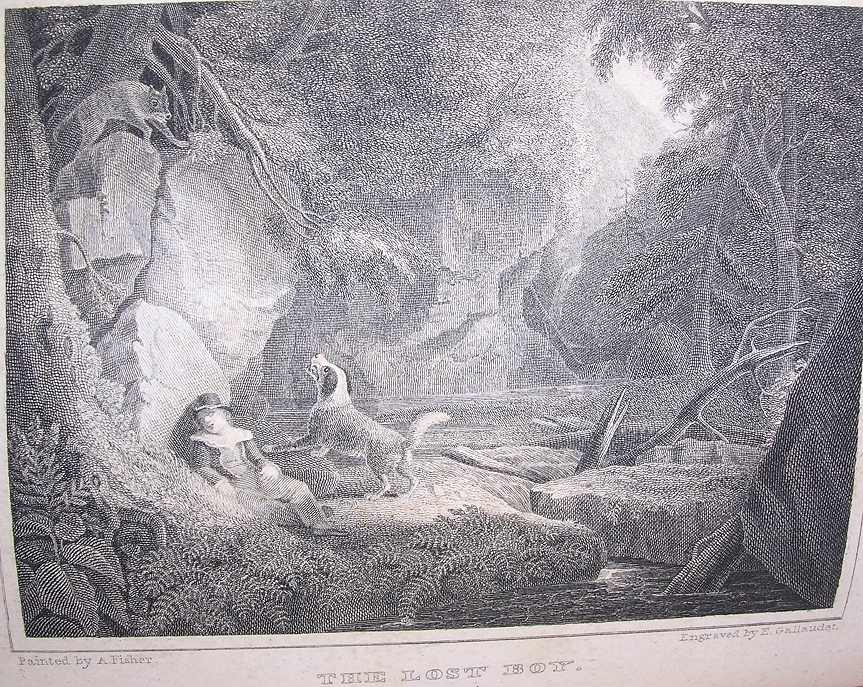

3. The Lost Boy, from a Painting by A. Fisher, belonging to that Artist, and engraved by E. Gallaudet … 27

4. Just Seventeen—engraved by J. Cheney, after a Portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence … 141

5. Music (St Cecelia)—engraved by E. Gallaudet after Dominichino … 107

6. Blind Mother—engraved by J. Andrews, after Lescot … 187

7. Isabel—painted by S. Newton, and engraved by M. J. Danforth … 217

8. The Shadow—painted by A. Fisher and engraved by J. Andrews … 247

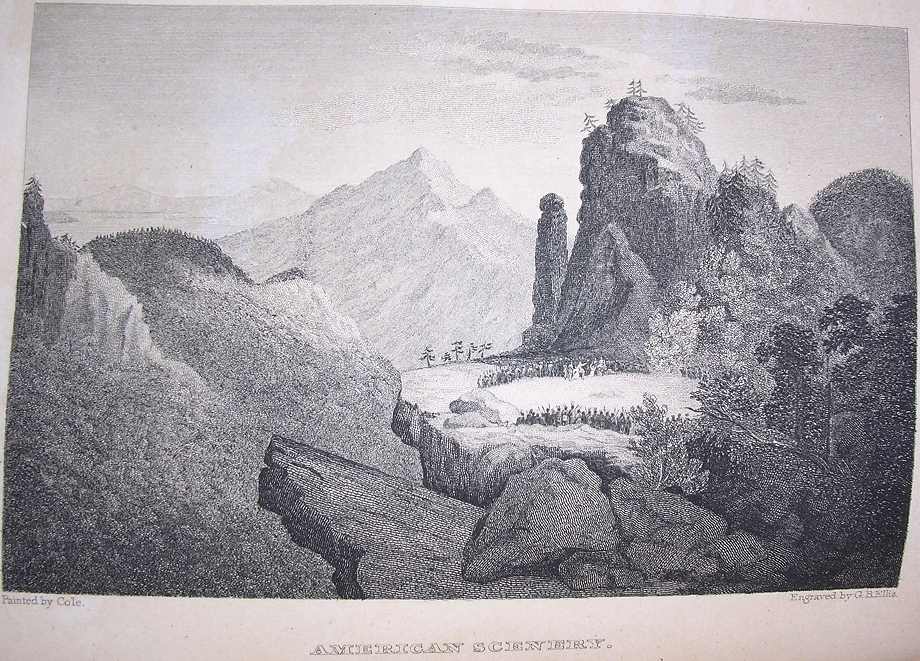

9. American Scenery—engraved by G. B. Ellis, from a Painting by T. Cole, in the possession of D. Wadsworth, Esq. of Hartford, Connecticut … 55

10. The Snow Shoe—drawn by Lieut. Hood, of the Royal British Navy, and engraved by O. Pelton … 285

11. New Tyrolese Waltz … 313

-----

[p. 6 blank]

-----

[p. vii]

CONTENTS.

—

Page.

The Mysteries of Life—By Orville Dewey … 9

To a City Pigeon [N. P. Willis] … 24

To the Moonbeams—By Hannah F. Gould … 26

The Lost Boy—By O. W. H. … 27

To —— … 28

Religion of the Sea—By F. W. P. Greenwood … 29

Sights from a Steeple [Nathaniel Hawthorne] … 41

Lake Superior—By S. G. Goodrich … 52

Lines—By L.M…t … 54

American Scenery … 55

The Fated Family … 57

Remembrance—By Charles West Thomson … 83

Ronda—By the Author of ‘A Year in Spain’ [Alexander Slidell Mackenzie] … 85

A Thought—By P. M. Wetmore … 106

Ode on Music—By Grenville Mellen … 107

I meet them in my Dreams—By Mrs L. P. Smith … 114

The Haunted Quack. A Tale of a Canal Boat—By Joseph Nicholson [Nathaniel Hawthorne] … 117

-----

p. viii

The Midnight Mail—By H. F. Gould … 138

Lines … 140

Just Seventeen … 141

Te Zahpahtah. A Sketch from Indian History—By the Author of ‘Tales of the Northwest’ [William Joseph Snelling] … 143

Return to Connecticut—By Mrs Sigourney … 152

The New England Village … 155

The Birth of Thunder. A Dahcotah Legend—By J. Snelling … 177

The Indian’s Burial of his Child—by Mrs Sigourney … 184

To the Witch Hazel … 186

The Blind Mother [N. P. Willis] … 187

The Adventurer—By J. Neal? … 189

To —— By O. W. B. Peabody … 213

To a Lady on her Thirtieth Birthday … 216

Isabel … 217

The Village Musician—By James Hall … 219

The Shadow … 247

Lord Vapourcourt; or a November Day in London [Alexander H. Everett] … 249

Farewell … 284

The Snow Shoe—By J. S. [William Joseph Snelling] … 285

The Captive’s Dream—By S. G. Goodrich … 288

Mary Dyre—By Miss Sedgwick … 294

The Waltz … 313

The Alchymist—By S. J. H. … 314

Oriental Mysticism—By L. W. [Leonard Woods] … 315

The Last Request—By B. B. Thatcher … 319

-----

[p. 9]

THE TOKEN.

—

THE MYSTERIES OF LIFE.

BY GRENVILLE DEWEY.

—

To the reflecting mind, especially if it is touched with any influences of religious contemplation or poetic sensibility, there is nothing more extraordinary, than to observe with what obtuse, dull, and commonplace impressions most men pass through this wonderful life, which Heaven has ordained for us. Life, which, to such a mind, means everything momentous, mysterious, prophetic, monitory, trying to the reflections, and touching to the heart, to the many is but a round of cares and toils, of familiar pursuits and formal actions. Their fathers have lived; their children will live after them; the way is plain; the boundaries are definite; the business is obvious; and

-----

p. 10

this to them is life. They look upon this world as a vast domicil, or an extensive pleasure ground; the objects are familiar; the implements are worn; the very skies are old; the earth is a pathway for those that come and go, on earthly errands; the world is a working-field, a warehouse, a market-place,—and this is life.

But life indeed—the intellectual life, struggling with its earthly load, coming it knows not whence, going it knows not whither, with an eternity unimaginable behind it, with an eternity to be experienced before it, with all its strange and mystic remembrances, now exploring its past years as if they were periods before the flood, and then gathering them within a space as brief and unsubstantial as if they were the dream of a day—with all its dark and its bright visions of mortal fear and hope; life, such as life, is full of mysteries. In the simplest actions, indeed, as well as in the loftiest contemplations, in the most ordinary feelings, as well as in the most abstruse speculations, mysteries meet us everywhere, mingle with all our employments, terminate all our views.

The bare act of walking has enough in it to fill us with astonishment. If we were brought into existence in the full maturity of our faculties, if experience had not made us dull, as well as confident, we should feel a strange and thrilling doubt, when we took one

-----

p. 11

step, whether another would follow. We should pause at every step, with awe at the wonders of that familiar action. For who knows anything of the mysterious connexion and process, by which the invisible will governs the visible frame? Who has seen the swift and silent messengers, which the mind sends out to the subject members of the body? Philosophers have reasoned upon this, and have talked of nerves, and have talked of delicate fluids, as transmitting the mandates of the will; but they have known nothing. No eye of man, nor penetrating glance of his understanding, has searched out those hidden channels, those secret agencies of the soul in its mortal tenement. Man indeed can construct machinery, curious, complicated, and delicate, though far less than that of the human frame, and with the aid of certain other contrivances and powers, he can cause it to be moved; but to cause it to move itself, to impart to it an intelligent power to direct its motions whithersoever it will, this is the mysterious work of God.

Nay, the bare connexion of mind with matter, is itself a mystery. The extremes of the creation are here brought together, its most opposite and incongruous elements are blended, not only in perfect harmony, but in the most intimate sympathy. Celestial life and light mingle, nay, and sympathize, with

-----

p. 12

dark, dull, and senseless matter. The boundless thought hath bodily organs. That which in a moment glances through the immeasurable hosts of heaven, hath its abode within the narrow bounds of nerves, and limbs, and senses. The clay beneath our feet is built up into the palace of the soul. The sordid dust we tread upon, forms, in the mystic frame of our humanity, the dwelling-place of high-reasoning thoughts, fashions the chambers of imagery, and moulds the heart, that beats with every lofty and generous affection. Yes, the feelings that soar to heaven, the virtue that is to win the heavenly crown, flows in the life-blood, that in itself is as senseless as the soil from which it derives its nourishment. Who shall explain to us this mysterious union—tell us where sensation ends, and thought begins, or where organization passes into life? There have been philosophers who have reasoned about this, materialists and immaterialists; and under their direction, the powers of matter and spirit have been marshalled in the contest, for ascendancy in this human microcosm; but the war has been fruitless; the argument futile; philosophers have settled nothing, proved nothing for they knew nothing.

Turn to what pursuit of science, or point of observation we will, and it is still the same. In every department of thought and study, we sooner or later

-----

p. 13

come to a region, into which our inquiries cannot penetrate. Everywhere our thoughts run out into the vast, the indefinite, the incomprehensible; time stretches to eternity, place to immensity, calculation to ‘numbers without number’ being to Infinite Greatness. Every path of our reflections brings us at length to the shrine of the unknown and the unfathomable, where we must sit down, and receive with devout and childlike meekness, if we receive at all, the voice of the oracle within.

Even the purest demonstrations in philosophy and the mathematics, often result in mysteries, and paradoxes. Matter that is finite, is infinitely divisible. A drop of water may be balanced against the universe. That, gentle reader, if thou hast ever chanced to hear of it, is the hydrostatic paradox. But there are pneumatic paradoxes too, and metallic wonders, wrought in the dark and silent mine, and geologic marvels, everywhere disclosed in the capacious bosom of the earth, in which flood and fire seem so mysteriously to have struggled together. Nor is there a plant so humble, no hyssop by the wall, nor flower nor weed in the garden, that springeth from the bosom of that earth, but it is an organized and living mystery. The secrets of the abyss are not more inscrutable, than the work that is wrought in its hidden germ. The goings on of the heavens are

-----

p. 14

not more incomprehensible than its growth, as it waves in the breeze. Its life, that which constitutes its life, who can tell us what it is? The functions that contribute to its growth, flowering, and fruit, the processes of secretion, the organs or the affinities by which every part receives the material that answers its purpose, who can unfold or explain them? Yes, the simplest spire of grass has wonders in it, in which the wisest philosopher may find a reason for humility, and the proudest skeptic an argument for faith.

Life, I repeat—and I say, let the dull in thought, let the children of sense be aroused by the reflection—life is full of mysteries. If we were wandering through the purlieus of a vast palace, and found here and there a closed door, or an inaccessible entrance, over which the word ‘MYSTERY’ was written, how would our curiosity be awakened by the inscription! Life is such a wandering; the world is such a structure; and over many a door forbidding all entrance, and over many a mazy labyrinth, is written the startling inscription that tells us of our ignorance, and announces to us unseen and unimaginable wonders. The ground we tread upon is not dull, cold soil, not the mere paved way, on which the footsteps of the weary and busy are hasting, not the mere arena on which the war of mercantile competition is waged; but ‘we tread upon enchanted ground’

-----

p. 15

The means of communication with this outward scene, are all mysteries. Anatomists may explain the structure of the eye and ear, but they leave inexplicable things behind;—seeing and hearing are still mysteries. The organ that collects within it the agitated waves of the air, the chambers of sound that lie beyond it, after all dissection and analysis, are still labyrinths and regions of mystery. And that little orb, the eye, which gathers in the boundless landscape at a glance, which in an instant measures the near and the distant, the vast and the minute, which brings knowledge from ten thousand objects in one commanding act of vision—what a mystery is that?

And then, if the soul communicates with the outward world, through mysterious processes, what power has that world—its objects, its events, its changes, its varying hues, its many toned voices, what mysterious power have they, to strike the secret springs of the soul within?

‘It may be a sound—

A tone of music—summer’s eve—or spring—

A flower—the wind—the ocean—which shall wound,

Striking the electric chain, wherewith we are darkly bound;

And how and why we know not, nor can trace

Home to its cloud this lightning of the mind.’

But if nature is bound with almost magic spells of

-----

p. 16

association to our maturer years, what a pure and fresh mystery is it to our childhood! Ah! Childhood—beautiful mystery!—how does nature lie all around thee, as a treasure-house of wonders. Sweet and gentle season of being! whose flowers bring on the period of ripening, or bloom but to wither and fade in their loveliness—time of ‘thick coming’ joys and tears! of tears that pass quickly away, as if they did not belong to thee, of joys that linger and abide long, and yet make the long day short—time of weakness! yet of power to charm the eye of sages from their lore;—Childhood! what a mystery art thou, and what mysteries dost thou deal with? What mystery is there in thy unfolding faculties, that call forth wonder from those that gaze upon thee, and seem to thyself at times, almost as if they were strange reminiscences of an earlier being! What mystery is there in thy thoughts, when thou art first struggling to grasp the infinite and eternal! when thou art told of immortal regions where thou shalt wander onward and onward forever, and sayest, even to the teaching voice of authority, ‘It cannot, father! it cannot be!’

And there are mysteries, too, thickly strewed all along the moral path of this wonderful being. There are ‘mysteries of our holy religion.’ Miracles of power, giving attestation to its truth, ushered it into the world. Wonders of heavenly mercy are displayed

-----

p. 17

in its successive triumphs over the human soul. Gracious interpositions, too, of the teaching Spirit and a succouring Providence, help the infirmities and struggles of the faithful.

And the results, moreover, of this great and solemn trial of human nature, that is passing on earth, are as mysterious as the process—the heavenly interposition and the human effort, and these, too, alike mysterious—the heavenly interposition, certain, but indefinable; the human will, strangely balanced somewhere, but nobody can tell where, between necessity and freedom.

Goodness, in the heart, is a mystery. No language can define it, which does not equally need definition. No man can tell what it is. No man can know, but by an inward experience, and an experience in reality inexpressible. Goodness is a breath in the soul, we know not from whence; it cometh and it goeth, like ‘the wind that bloweth where it listeth:’ it is the inspiration of the Almighty.

And sin!—how great and tremendous is that mystery! That beneath these serene and pure heavens, which beam with the benignity of their Maker; that amidst the fair earth, amidst ten thousand forms of perfection—that where all else is perfect, the spoiler should have gone forth to mar and to crush the noblest and fairest—this is ‘the mystery of iniquity,

-----

p. 18

that hath been hidden from ages,’ and is not yet fully unfolded. This was the theme that tasked and tried the meditations of the old philosophers. Unde malum et quare? ‘Whence is evil, and why?’ Noble-minded old men!—sages of the elder world!—when I look at the busy and giddy throng, that think of nothing but pleasure or gain, that question not this mysterious life nor this mighty sphere, but to ask for the way to gratification and profit, I turn to you with veneration, and refreshment of spirit. I pay a homage to your sublime meditations, less only than that which I give to the inspiration of apostles, and the visions of holy martyrs. Ay, christian men of this every-day world may call you heathens, and those who bear of the christian religion nothing but the name, may think themselves entitled to look upon you with pity or scorn; but, contrasted with them, ye are as stars that shine from the depths of the midnight heaven, compared with the insects that sport in the beams of the noontide sun.

The mysteries of our present being, though met with in daily experience, though recognised by the severest philosophy, are never perhaps more sensibly, or, so to speak, consciously shadowed forth to us, than in that scene of strangely mingled experience and illusion, that world veiled from the eyes of philosophy—the world or our dreams. Mr Hogg

-----

p. 19

somewhere remarks, and it seems to be more than a poetical fancy, that our dreams are emphatically mysteries, hitherto sacred from metaphysical analysis. The writer hopes he may be excused, therefore, if he introduces, as appropriate to the meditations of this paper, a dream of his own.

An excursion for health carried me, some years ago, through the beautiful villages of Concord and Lancaster, to the brow of the noble Wachusett. It was in the month of our summer’s glory—June. I know not how it may appear to others; but that enjoyment, leading to surfeit and oppression, which is often described as attending upon one class of our pleasures, seems to me as more than realized in the overpowering, the almost oppressive, the mysterious delight with which we gaze upon the ever-renewed and brightened vision of nature. Such it was to me; and when the evening came, its calmness was as grateful to me, as the rest which hospitality offered.

Yet it brought its own fascination. The moon shed down from her calm and lofty sphere, a more sacred beam than that of day. Her light seemed like an emanation, an element for holy thought, in which there was something like consciousness and witnessing to the thoughts of mortals. The breeze, as it went up the mountain’s side and touched the forest boughs, seemed like a living spirit. The summit,

-----

p. 20

rising towards heaven and resting in a solemn and serene light, appeared like a mount of meditation, where some holy sufferer had retired from the world to pray, and where angels were ascending and descending.

Fatigued and exhausted, I sought repose at an early hour,—and soon fell into that half sleeping and half waking state, with which the diseased and troubled, at least, are so well acquainted. It is the well known and frequent effect of this state of partial consciousness, to give a mysterious and preternatural importance to everything that attracts the notice of the wandering senses. Now and then, an evening traveller passed by; but that was not the simple character with which my imagination invested him. He was a fierce rider from the battle-field—and as he rushed by upon the sounding mountain pavement, he seemed to bear upon his tread, the fate of empires. Then, a sound of laughter and shout of revelry reached me from a neighbouring ale-house, and it appeared like the discordant mockery of fiends over the wreck of kingdoms. And ever and anon, the passing breeze shook the casement of my window, and the sound, in my ear, seemed stern as the voice of destiny, and struck me with that inexplicable awe, that attends the slightest jar of an earthquake.

At length, I sunk into a deeper sleep; but still the

-----

p. 21

confused images of my half conscious state, mingled with the deeper reveries of my dream. I dreamed, as I often do when awake, of men, and life, and the crowded world. The procession of human generations passed before me. The wandering Tartar flew by me in his sledge over the frozen solitudes of the North. The turbaned Turk moved slowly on, by the many shores of his rich and glorious domain. The politic, bustling, busy European passed over the theatre of my vision, and it was a theatre of merchandize. And then, again, the wilds of the New World were opened to me, and I saw the stealthy Indian retiring from thicket to thicket, and the white man pressed hard upon his retreating steps. Then the palaces and courts of royalty rose before me, and I saw the gay and gorgeous train that thronged them, and heard from many a recess and by-path, the sighs of disappointed ambition. Anon, the camp, with its mingled order and confusion, came upon the wayward fancies of my dream; and the fearful tread of a host drew near, and music from unnumbered instruments burst forth, and swelled gloriously up to heaven. And then suddenly the scene changed, and I thought it was music for the gay assembly and the dance; and a multitude innumerable wandered through boundless plains in pursuit of pleasure. But immediately—either in the strange vagaries of my

-----

p. 22

dream, or according to the broken memory of it—it appeared to be no longer a multitude, but a mighty city of immeasurable extent;—and then the countless habitations of far distant countries came with the range of my vision, and the scenes of domestic abode and all the mazy struggle of human life, were beneath my eye. I saw the embrace of love; I heard the song of gladness; and then the wailings of infancy were in my ears, and stern voices seemed to hush them. In another quarter, the throng of pleasure, and the pall of death passed on, and went different ways, as it seemed, but in a shocking vicinity to each other, and in strangely mingled and mournful confusion; and I thought of human weal and wo, and of this world’s great fortunes, and of the mystery of this life, and of God’s wisdom, till it seemed to me that my heart would break with its longing for further knowledge, and my pillow was wet with the tears of my dream.

As my head was bowed down in meditation and sorrow, it suddenly appeared to me that an unusual and unearthly light was breaking around me. I instantly lifted my eyes, for a thrilling and awful expectation came upon me. I thought of the Judgment, and almost expected to behold the Son of Man in the clouds of heaven. But I immediately perceived that the vision was to me alone; for the light did not spread far, and proceeded from only one luminous cloud. As I gazed upon it, features of more than

-----

p. 23

mortal loveliness became visible, though the form was partly veiled from me in the glorious brightness that surrounded it. I imagined that I perceived a resemblance to the countenance of one that I had known and loved on earth; and I girded up the powers of my mind, as I have often thought I should do, in my waking hours, to meet a spirit from the other world. But the first words that fell upon my ear, instead of inspiring me with the expected terror, spread a sacred tranquillity [sic] through all my faculties. ‘Mortal!’—the voice said—‘once a fellow-mortal!’—and no earthly tongue can express the soothing sweetness and tenderness that flowed into those words—“be patient,’ it said, ‘be strong; fear not; be not troubled. If thou couldst know!—but I may not tell thee—else would not thy faith be perfected:—be yet patient; trust in God; trust in him, and be happy!’ The bright cloud was borne as by the gentlest breath of air away from me; the features slowly faded, but with such a smile of ineffable benignity and love lingering upon the countenance, that in the ecstasy of my emotions I awoke.

I awoke; the songs of the morning were around me; the sun was high in heaven; the earth seemed to me clothed with new beauty. I went forth with a firmer step, and a more cheerful brow, resolving to be patient and happy till I also ‘should see as I am seen, and know even as I am know.’

-----

[p. 24]

TO A CITY PIGEON.

—

Stoop to my window, thou beautiful dove!

Thy daily visits have touched my love!

I watch thy coming, and list the note

That stirs so low in thy mellow throat,

And my joy is high

To catch the glance of thy gentle eye.

Why dost thou sit on the heated eaves,

And forsake the wood with its freshened leaves?

Why dost thou haunt the sultry street,

When the paths of the forest are cool and sweet?

How canst thou bear

This noise of people—this breezeless air?

Thou alone of the feathered race,

Dost look unscared on the human face;

Thou alone, with a wing to flee,

Dost love with man in his haunts to be;

And the ‘gentle dove’

Has become a name for trust and love.

-----

p. 25

A holy gift is thine, sweet bird!

Thou ’rt named with childhood’s earliest word;

Thou ’rt linked with all that is fresh and wild

In the prisoned thoughts of the city child—

And thy even wings

Are its brightest image of moving things.

It is no light chance, Thou art set apart

Wisely by him who tamed thy heart—

To stir the love for the bright and fair,

That else were sealed in the crowded air—

I sometimes dream

Angelic rays from thy pinions stream.

Come, then, ever when daylight leaves

The page I read, to my humble eaves;

And wash thy breast in the hollow spout,

And murmur thy low, sweet music out—

I hear and see

Lessons of heaven, sweet bird, in thee!

—

-----

[p. 26]

TO THE MOONBEAMS.

BY HANNAH F. GOULD.

—

Away! Away! from her favorite bower,

Where ye loved to come in the evening hour,

To silver the leaf, and smile on the flower—

Away! away! for the maid ye seek

Hath a clouded eye, and a pale, pale cheek,

As the lonely walk, and the flowers all speak.

Away! for the voice that ye could win

To flow with the melody found within,

’T is hushed, ’t is gone, as it never had been;—

And the fearful harp that ye could make

Its deepest and tenderest tones awake,

It hath not a string but it fain would break.

Away! to the slope of the dew-bright hill,

Where the sod is fresh and the air is chill,

Where the marble is white and all is still;

But never reveal who there is led

By your light, to mourn for the early dead,

And weep o’er the lost, in her lonely bed!

-----

Painted by A. Fisher. Engraved by E. Gallaudat.

THE LOST BOY.

-----

[p. 27]

THE LOST BOY.

BY O. W. H.

—

How sweet to boyhood’s glowing pulse

The sleep that languid Summer yields,

In the still bosom of the wild,

Or in the flowery fields!

So art thou slumbering, lonely boy—

But ah! how little deemest thou

The hungry felon of the wood,

Is glaring on thee now!

He crept along the tangled glen,

He panted up the rocky steep,

He stands and howls above thy head,

And thou art still asleep!

No trouble mars thy peaceful dream;

And though the arrow, winged with death,

Goes glancing near thy thoughtless heart,

Thou heedest not its breath.

-----

p. 28

Sleep on! the danger all is past,

The watch-dog, roused, defends thy breast,

And well the savage prowler knows

He may not break thy rest!

—

TO ——.

Blessed thou art, and shalt be! though thy day

Hath not been cloudless, nor unknown the tear

Of secret grief, too early and severe—

Darkness and sorrow soon shall pass away.

As the disciples, when their aching eye

Caught the first dawning of the eastern light

That saw their Master rising—let thy sight

In faith and hope be ever fixed on high.

Therefore in patience wait the heavenly prize:

Then shall thy deeds in sweet remembrance rise

Before the throne. And why should earthly love,

When on thy cheek the seal of death is set,

Shed the vain tear, or witness with regret

The beautiful made permanent above?

-----

[p. 29]

RELIGION OF THE SEA.

BY F. W. P. GREENWOOD.

—

‘In every object here I see

Something, O Lord, that leads to thee!

Firm as the rocks thy promise stands,

Thy mercies countless as the sands,

Thy love a sea immensely wide,

Thy grace an ever flowing tide.’

J. Newton

The ocean is wonderful and divine in its forms and changes and sounds, in its grandeur, its beauty, its variety, its inhabitants, its uses and its mysteries, in all that strikes the sense and is immediately apprehended by the understanding. But besides all these, and lying deeper than all, it possesses a moral interest, which is partly bestowed upon it, and partly borrowed from it, by the mind of man. The soul finds in it a fund of high spiritual associations. Analogies are perceived in it, which connect it most affectingly with our mortal life, with dread eternity, and with

-----

p. 30

Almighty God himself, the source and end of all. And thus it becomes a principal link in that great chain of purpose and sympathy, with which the Creator has bound up all matter and mind, together with his own infinite being, in one consenting whole.

The sea has often been likened to this our life. Poetry is fond of remarking resemblances between it and the passions and fortunes of humanity. Our contemplations launch forth on its capacious bosom, and gather up the images and shadowings of our existence and fate, of what we are, and what is appointed to us. Do we see its multitudinous waves rushing blindly and impetuously along wherever they are driven by the lashing wind? They remind us of the tempest of an angry mind,, or the tumult of an enraged people. Are the waves hushed, and is a calm breathed over the floods? It is the similitude of a peaceful breast, of a composed and placid spirit, or a quiet, untroubled time. Doubts, anxieties, and fears pass over our minds, as clouds do over the sea, tinging them, as the clouds tinge the waters, with their deep and threatening hues. Does a beaming hope or a golden joy break in suddenly upon us, in the midst of care or misfortune? What is it but a ray of light, such as we sometimes behold sent down from the rifted sky, shining alone in the dark horizon, a sun-burst on a sullen sea?

-----

p. 31

Then how often are the vicissitudes of life compared with the changes of the ocean. Who that has been abroad on the sea, who that has heard or read anything of its phenomena, does not know that to the most propitious winds and skies which can bless the mariner, frequently succeed those which are the most adverse and destructive; that the morning may rise with the fairest promises, bringing the favoring breeze, and smiling over the pleasant water, and ere the evening falls, or before high noon is come, the scene may be wrapt in gloom, the steady gale may be converted into the savage blast, the gay sunbeams may be followed by the blue lightnings, and the floods above be poured down on the floods below, as if together they were determined, as of old, to drown and desolate the world? And do not these things take place in the voyage of human life? Who knows not how often youth sets sail with flattering hopes and brilliant prospects, which are changed before manhood, into dreary disappointment or black despair? Who knows not how often and how suddenly the sun of prosperity may be covered up from sight, and its glowing rays be quenched in the coldness and darkness and fearfulness of howling adversity? Who knows not that in the midst of joy and peace, the billows of affliction may all at once rise up, and roll in upon the soul? ‘All thy waves and thy billows

-----

p. 32

are gone over me,’ cries the mourning Psalmist; and again he complains, ‘Thou hast laid me in the lowest pit, in darkness, in the deeps. Thy wrath lieth hard upon me, and thou hast afflicted me with all thy waves.’ And there is not, perhaps, in all literature, sacred or profane, a more striking image of dank, weltering, utter desolation, than is contained in the exclamation of the prophet Jonah. ‘The depth closed me round about,’ says he, ‘the weeds were wrapped about my head.’

Though no voyage, on the sea or in life, is free from vicissitudes, yet the same changes happen not to all, nor do all suffer the same or equal reverses. Our barks are all abroad on the wide surface of existence, and some experience more severe and frequent storms, or more baffling winds than others. For some, the gales of prosperity appear to blow, as we may say, tropically, so fair and steady is the course of fortune into which they seem to have fallen; while others appear to have encountered, almost at the outset, an unfavorable vein, which has opposed, wearied and persecuted them to the very end. To that end they all arrive, sooner or later. The ocean has many harbors; life has but one. It is safe and peaceful. There the tempests cease to rage, and all the winds of heaven fold up their wings, and rest. There the mariner reposes

-----

p. 33

from all his toils, and forgets his perils and fears, his watchings and fatigues. The billows are without; they foam and toss in vain. The sails are furled, and the anchors are dropped. ‘We sail the sea of life,’ says the poet,

‘We sail the sea of life—a calm one finds,

And one a tempest—and, the voyage o’er,

Death is the quiet haven of us all.’

Thus discourses the ocean on the great themes of mortality—the eloquent ocean, sounding forth incessantly, in its deep toned surges, a true and dignified philosophy; repeating to every shore the moral and the mystery of human life.

But it does something more. It is so vast, so uniform, so full, so all enveloping, that it leads the thoughts to a sublimer theme than life or time, to the theme of dread eternity. When contemplations on this subject are suggested by it, human life shrinks up into a stream, wandering through a varied land, now through flowers, and now through sands, now clearly and now turbidly, now smoothly and quietly, and now obstructed and chafed, till it is lost at last in the mighty ocean, which receives, and feels it not. There is nothing among the earthly works of God, which brings the feeling—for it can hardly be termed a conception—the feeling of eternity so powerfully

-----

p. 34

to the soul, as does the ‘wide, wide sea.’ We look upon its waves, succeeding each other continually, one rising up as another vanishes, and we think of the generations of men, which lift up their heads for a while and then pass away, one after the other, for all the noise and show they make, even as those restless and momentary waves. Thus the waves and the ages come and go, appear and disappear, and the ocean and eternity remain the same, undecaying and unaffected, abiding in the unchanging integrity of their solemn existence. We stand upon the solitary shore, and we hear the surges beat, uttering such grand, inimitable symphonies as are fit for the audience of cliffs and skies; and our minds fly back through years and years, to that time, when, though we were not and our fathers were not, those surges were yet beating, incessantly beating, making the same wild music, and heard alone by the overhanging cliffs, and the overarching skies, which silently gave heed to it, even as they do now. In the presence of this old and united company we feel on what an exceedingly small point we stand, and how soon we shall be swept away, while the surges will continue to beat on that very spot, and the cliffs and the skies will still lean over to hear. This is what may be called the feeling of eternity. Perhaps the feeling is rendered yet more intense, when we lie on our bed,

-----

p. 35

musing and watching, and hear the sonorous cadences of the waves coming up solemnly and soothingly through the stillness of night. It is as the voice of a spirit—as the voice of the spirit of eternity. The ocean seems now to be a living thing, ever living and ever moving, a sleepless influence, a personification of unending duration, uttering aloud the oracles of primeval truth.

‘Listen! the mighty being is awake,

And doth with his eternal motion make

A sound like thunder, everlastingly.’

Where are the myriads of men who have trodden its shores, and gone down to it in ships? They are passed away. Not a single trace has been left by all their armaments. Where are the old kingdoms which were once washed by its waves? They have been changed, and changed again, till a few ruins only tell where they stood. But the sea is all the same. Man can place no monuments upon it, with all his ambition and pride. It suffers not even a ruin to speak of his triumphs or his existence. It remains as young, as strong, as free, as when it first listened to the Almighty Word, and responded with all its billows to the song of the morning stars.

‘Time writes no wrinkle on thine azure brow;

Such as creation’s dawn beheld, thou rollest now.’

-----

p. 36

It is this immutability, which, more than any other of the attributes of ocean, perhaps, impresses our minds with the sentiment of eternity, and gives to it its character of superiority among the works of God. Earth never frees itself entirely from the subjection of man. It constantly receives and covers his fallen remains, indeed, but is made to bear memorials of the victor, even after he is vanquished. All over the world, we see the vestiges of former generations; their caves, their wells, their pyramids, their roads, their towers, their graves. But none of these things are on the sea. Its surface is unmarked but by its own commotions; and when it buries man or man’s works, the sepulture is sudden and entire; a plunge, a bubble, and the waters roll on as before, careless of the momentary interruption of their wonted flowing. Thus immutable, thus unworn and unsullied is ocean. To what shall it be compared, but to the highest subjects of thought, to life and to immortality? It allies itself in its greatness more with spirit than with matter. It holds itself above subjection or control. It seems to have a will, a liberty, and a power.

As these are high associations, they readily lead us up to Him who is above all height. There is a natural connexion between all sublime and pure sentiment, and the conception of Deity. All grandeur

-----

p. 37

directs us to him, because we have learnt that he is greatest. We cannot stop in the creature, after we have received any true ideas of the Creator. And thus God himself comes, as if by an influence of his spirit, into our minds, when we are looking upon the sea, or listening to its roar, and imbibing the emotions which it is so powerful to excite. Where he comes, he reigns. The conception of God, when it enters, takes the throne of authority among the other thoughts, and brings them into easy subordination. And then we think how inferior and dependent are all might and majesty, compared with his. The eternity of ocean becomes a brief type of the eternity of him who made it, and all its grandeur as a passing shadow of his. It does not, however, lose any of its interest, by this kind of inferiority. Nothing is lessened to the pious mind, by being esteemed less than the Supreme. It retains its connexion with eternity and God, and is exalted by its glorious dependence. It puts on the aspect, and speaks with the added solemnity of religion; telling us that all its power and magnificence are from the Maker, and that if it is full of beauty, and life, and usefulness, and mystery, it is because the Maker is good and wise and infinite. The sea has been called the religious sea. It is religious, as it suggests religious thoughts and emotions. And as the feelings excited

-----

p. 38

by a noble object in a contemplative soul, are always in some degree reflected back upon that object, the sea will appear to be in its own self religious; to know that it is lying in the hollow of the Almighty’s hand; to chant loud anthems to his praise in the noise of its rushing floods, and to send up its more quiet devotions in the breathing stillness of its calms. In short, we know nothing of the sea as we ought to know, we feel nothing of its best and sublimest inspirations, unless we receive from it, and communicate to it, the thoughts and feelings of religion; unless we grow devout as we gaze, and return from contemplating it with the consciousness that we have entered into a nearer union with God.

The moral associations which have now been described as naturally arising from the soul’s converse with the sea, are all in a great degree definite. The deep is, as it were, freighted and laden with them, and bears them richly to our receiving bosoms. And when we look out upon the ocean, without fixing on either of these associations as the direct subject of thought, it is the union of several or of all of them, which, almost unconsciously to us, produces such a strong impression within us. But besides these sentiments, which can be traced and numbered, there are feelings suggested by that magnificent object, which cannot so well, if at all, be defined. I believe

-----

p. 39

that no one, who loves nature, has let his soul go out on the sea, without experiencing emotions which he could not possibly explain, but which were as real as any that he ever felt. All that he can tell of them, is, that they are elevating and refining. Further than this he cannot communicate them, for they baffle all description and search. It seems to him, sometimes, as he waits and watches on the shore, that the great Spirit himself moves, as in the beginning, on the face of the waters, and speaks to him holy words, which, though he hears and imbibes, he cannot fully understand; which he knows not now, but will know hereafter. They come like whispers of that communion, intelligence, and consent which pervade creation. They teach us something of our unrevealed connexions, something of the unseen and unimaginable future; and, if so be that we are disposed to bring down all our faith and trust to that alone which we can touch and clearly define, they gently rebuke us for our coldness, and intimate to us that there are more, many more things in heaven and earth and sea, than are dreamt of in our philosophy.

I have spoken as I was able, and not as I could have desired, of the ‘great and wide sea.’ Let the rest be learnt by each one, where it can be learnt much better than from me, from the sea itself. If I

-----

p. 40

have induced a single individual, who has hitherto regarded it as a barren collection of waters, or a medium of traffic merely, to look upon it as something more wonderful, divine, and useful than this, I am satisfied. If his curiosity is at all excited, let him go to the sea-shore, and get wisdom. If his devout affections are at all moved, let him go to the ocean, and worship.

‘His choir shall be the moonlight waves,

When murmuring homeward to their caves;

Or, when the stillness of the sea,

Even more than music, breathes of Thee!’

Every object in nature yields instruction to the teachable and listening mind; but some objects utter a voice more powerful, more commanding, more thrilling than others. If we may find, as one of the best English poets tells us we may, ‘sermons in stones,’ in lifeless stones, what eloquent and soul-stirring addresses may we not hear from the living, glorious, beautiful, eternal sea!

—

-----

[p. 41]

SIGHTS FROM A STEEPLE.

—

So! I have climbed high, and my reward is small. Here I stand, with wearied knees, earth, indeed, at a dizzy depth below, but heaven far, far beyond me still. O that I could soar up into the very zenith, where man never breathed, nor eagle ever flew, and where the ethereal azure melts away from the eye, and appears only a deepened shade of nothingness! And yet I shiver at that cold and solitary thought. What clouds are gathering in the golden west, with direful intent against the brightness and the warmth of this summer afternoon! They are ponderous air ships, black as death, and freighted with the tempest; and at intervals their thunder, the signal-guns of that unearthly squadron, rolls distant along the deep of heaven. These nearer heaps of fleecy vapor—methinks I could roll and toss upon them the whole day long!—seem scattered here and there, for the repose of tired pilgrims through the sky. Perhaps—for who can tell?—beautiful spirits are disporting themselves there, and will

-----

p. 42

bless my mortal eye with the brief appearance of their curly locks of golden light and laughing faces, fair and faint as the people of a rosy dream. Or, where the floating mass so imperfectly obstructs the color of the firmament, a slender foot and fairy limb, resting too heavily upon the frail support, may be thrust through, and suddenly withdrawn, while longing fancy follows them in vain. Yonder again is an airy archipelago, where the sunbeams love to linger in their journeyings though space. Every one of those little clouds has been dipped and steeped in radiance, which the slightest pressure might disengage in silvery profusion, like water wrung from a sea-maid’s hair. Bright they are as a young man’s vision, and like them, would be realized in chillness, obscurity, and tears. I will look on them no more.

In three parts of the visible circle, whose centre is this spire, I discern cultivated fields, villages, white country-seats, the waving lines of rivulets, little placid lakes, and here and there a rising ground, that would fain be termed a hill. On the fourth side is the sea, stretching away towards a viewless boundary, blue and calm, except where the passing anger of a shadow flits across its surface, and is gone. Hitherward, a broad inlet penetrates far into the land; on the verge of the harbour, formed by its extremity, is a town; and over it am I, a watchman, all-heeding

-----

p. 43

and unheeded. O that the multitude of chimneys could speak, like those of Madrid, and betray, in smoky whispers, the secrets of all who, since their first foundation, have assembled at the hearths within! O that the Limping Devil of Le Sage would perch beside me here, extend his wand over this contiguity of roofs, uncover every chamber, and make me familiar with their inhabitants! The most desirable mode of existence might be that of a spiritualized Paul Pry, hovering invisible round man and woman, witnessing their deeds, searching into their hearts, borrowing brightness from their felicity, and shade from their sorrow, and retaining an emotion peculiar to himself. But none of these things are possible; and if I would know the interior of brick walls, or the mystery of human bosoms, I can but guess.

Yonder is a fair street, extending north and south. The stately mansions are placed each on its carpet of verdant grass, and a long flight of steps descends from every door to the pavement. Ornamental trees, the broad-leafed horse-chestnut, the elm so lofty and others whereof I know not the names, grow thrivingly among brick and stone. The oblique rays of the sun are intercepted by these green citizens, and by the houses, so that one side of the street is a shaded

-----

p. 44

and pleasant walk. On its whole extent there is now but a single passenger, advancing from the upper end; and he, unless distance, and the medium of a pocket spy-glass do him more than justice, is a fine young man of twenty. He saunters slowly forward, slapping his left hand with his folded gloves, bending his eyes upon the pavement, and sometimes raising them to throw a glance before him. Certainly, he has a pensive air. Is he in doubt, or in debt? Is he, if the question be allowable, in love? Does he strive to be melancholy and gentlemanlike?—Or, is he merely overcome by the heat? But I bid him farewell, for the present. The door of one of the houses, an aristocratic edifice, with curtains of purple and gold waving from the windows, is now opened, and down the steps come two ladies, swinging their parasols, and lightly arrayed for a summer ramble. Both are young, both are pretty; but methinks the left hand lass is the fairer of the twain; and though she be so serious at this moment, I could swear that there is a treasure of gentle fun within her. They stand talking a little while upon the steps, and finally proceed up the street. Meantime, as their faces are now turned from me, I may look elsewhere.

Upon that wharf, and down the corresponding street, is a busy contrast to the quiet scene which I have just noticed. Business evidently has its centre

-----

p. 45

there, and many a man is wasting the summer afternoon in labor and anxiety, in losing riches, or in gaining them, when he would be wiser to flee away to some pleasant country village, or shaded lake in the forest, or wild and cool sea-beach. I see vessels unlading at the wharf, and precious merchandise strown upon the ground, abundantly as at the bottom of the sea, that market whence no goods return, and where there is no captain nor supercargo to render an account of sales. Here, the clerks are diligent with their paper and pencils, and sailors ply the block and tackle that hang over the hold, accompanying their toil with cries, long-drawn and roughly melodious, till the bales and puncheons ascend to upper air. At a little distance, a group of gentlemen are assembled round the door of a warehouse. Grave seniors be they, and I would wager—if it were safe, in these times, to be responsible, for any one—that the least eminent among them, might vie with old Vincentio, that incomparable trafficker of Pisa. I can even select the wealthiest of the company. It is the elderly personage in somewhat rusty black, with powdered hair, the superfluous whiteness of which is visible upon the cape of his coat. His twenty ships are wafted on some of their many courses by every breeze that blows, and his name—I will venture to say, though I know it not—is a familiar sound among

-----

p. 46

the far separated merchants of Europe and the Indies. But I bestow too much of my attention in this quarter. On looking again to the long and shady walk, I perceive that the two fair girls have encountered the young man, and, after a sort of shyness in the recognition, he turns back with them. Moreover, he has sanctioned my taste in regard to his companions by placing himself on the inner side of the pavement, nearest the Venus to whom I—enacting, on a steeple-top, the part of Paris on the top of Ida—adjudged the golden apple.

In two streets, converging at right angles towards my watch-tower, I distinguish three different processions. One is a proud array of volunteer soldiers in bright uniform, resembling, from the height whence I look down, the painted veterans that garrison the windows of a toy-shop. And yet, it stirs my heart; their regular advance, their nodding plumes, the sun-flash on their bayonets and musket-barrels, the roll of their drums ascending past me, and the fife ever and anon piercing through—these things have wakened a warlike fire, peaceful though I be. Close to their rear marches a battalion of school boys, ranged in crooked and irregular platoons, shouldering sticks, thumping a harsh and unripe clatter from an instrument of tin, and unfortunately aping the intricate manœuvres of the foremost band. Nevertheless,

-----

p. 47

as slight differences are scarcely perceptible from a church spire, one might be tempted to ask, ‘Which are the boys?’—or rather, ‘Which the men?’ but, leaving these, let us turn to the third procession, which, though sadder in outward show, may excite identical reflections in the thoughtful mind. It is a funeral. A hearse, drawn by a black and bony steed, and covered by a dusty pall; two or three coaches rumbling over the stones, their drivers half asleep; a dozen couple of careless mourners in their every day attire; such was not the fashion of our fathers, when they carried a friend to his grave. There is now no clang of passing bell, to proclaim sorrow to the town. Was the King of Terrors more awful in those days than in our own, that wisdom and philosophy have been able to produce this change? Not so. Here is a proof that he retains his proper majesty. The military men, and the military boys, are wheeling round the corner, and meet the funeral full in the face. Immediately, the drum is silent, all but the tap that regulates each simultaneous foot-fall. The soldiers yield the plan to the dusty hearse, and unpretending train, and the children quit their ranks, and cluster on the sidewalks, with timorous and instinctive curiosity. The mourners enter the churchyard at the base of the steeple, and pause by an open grave among the burial stones; the lightning glimmers on

-----

p. 48

them as they lower down the coffin, and the thunder rattles heavily while they throw the earth upon its lid. Verily, the shower is near, and I tremble for the young man and the girls, who have now disappeared from the long and shady street.

How various are the situations of the people covered by the roofs beneath me, and how diversified are the events at this moment befalling them! The new-born, the aged, the dying, the strong in life, and the recent dead, are in the chambers of these many mansions. The full of hope, the happy, the miserable, and the desperate, dwell together within the circle of my glance. In some of the houses over which my eyes roam so coldly, guilt is entering into hearts that are still tenanted by a debased and trodden virtue,—guilt is on the very edge of commission, and the impending deed might be averted; guilt is done, and the criminal wonders if it be irrevocable. There are broad thoughts struggling in my mind, and, were I able to give them distinctness, they would make their way in eloquence. Lo! the rain-drops are descending.

The clouds, within a little time, have gathered over all the sky, hanging heavily, as if about to drop in one unbroken mass upon the earth. At intervals, the lightning flashes from their brooding hearts, quivers, disappears, and then comes the thunder,

-----

p. 49

travelling slowly after its twin-born flame. A strong wind has sprung up, howls through the darkened streets, and raises the dust in dense bodies, to rebel against the approaching storm. The disbanded soldiers fly, the funeral has already vanished like its dead, and all people hurry homeward—all that have a home; while a few lounge by the corners, or trudge on desperately, at their leisure. In a narrow lane which communicates with the shady street, I discern the rich old merchant, putting himself to the top of his speed, lest the rain should convert his hair-powder to a paste. Unhappy gentleman! By the slow vehemence, and painful moderation wherewith he journeys, it is but too evident that Podagra has left its thrilling tenderness in his great toe. But yonder, at a far more rapid pace, come three other of my acquaintance, the two pretty girls and the young man, unseasonably interrupted in their walk. Their footsteps are supported by the risen dust, the wind lends them its velocity, they fly like three sea-birds driven landward by the tempestuous breeze. The ladies would not thus rival Atalanta, if they but knew that any one were at leisure to observe them. Ah! as they hasten onward, laughing in the angry face of nature, a sudden catastrophe has chanced. At the corner where the narrow lane enters into the street, they come plump against the old merchant, whose

-----

p. 50

tortoise motion has just brought him to that point. He likes not the sweet encounter; the darkness of the whole air gathers speedily upon his visage, and there is a pause on both sides. Finally he thrusts aside the youth with little courtesy, seizes an arm of each of the two girls, and plods onward, like a magician with a prize of captive fairies. All this is easy to be understood. How disconsolate the poor lover stands! regardless of the rain that threatens an exceeding damage to his well-fashioned habiliment, till he catches a backward glance of mirth from a bright eye, and turns away with whatever comfort it conveys.

The old man and his daughters are safely housed, and now the storm lets loose its fury. In every dwelling I perceive the faces of the chambermaids as they shut down the windows, excluding the impetuous shower, and shrinking away from the quick fiery glare. The large drops descend with force upon the slated roofs, and rise again in smoke. There is a rush and roar, as of a river through the air, and muddy streams bubble majestically along the pavement, whirl their dusky foam into the kennel, and disappear beneath iron grates. Thus it was that Arethusa sunk. I love not my station here aloft, in the midst of the tumult which I am powerless to direct or quell, with the blue lightning wrinkling on my brow, and the thunder muttering its first awful

-----

p. 51

syllables in my ear. I will descend. Yet let me give another glance to the sea, where the foam breaks out in long white lines upon a broad expanse of blackness, or boils up in far distant points, like snowy mountain tops in the eddies of a flood; and let me look once more at the green plain, and little hills of the country, over which the giant of the storm is striding in robes of mist, and at the town, whose obscured and desolate streets might beseem a city of the dead: and turning a single moment to the sky, now gloomy as an author’s prospects, I prepare to resume my station on lower earth. But stay! A little speck of azure has widened in the western heavens; the sunbeams find a passage, and go rejoicing through the tempest; and on yonder darkest cloud, born, like hallowed hopes, of the glory of another world, and the trouble and tears of this, brightens forth the rainbow!

—

-----

[p. 52]

LAKE SUPERIOR.

BY S. G. GOODRICH.

—

‘Father of Lakes!’ thy waters bend

Beyond the eagle’s utmost view,

When, throned in heaven, he sees thee send

Back to the sky its world of blue.

Boundless and deep, the forests weave

Their twilight shade thy borders o’er,

And threatening cliffs, like giants, heave

Their rugged forms along thy shore.

Pale Silence, mid thy hollow caves,

With listening ear in sadness broods,

Or startled Echo, o’er thy waves

Sends the hoarse wolf-notes of thy woods.

Nor can the light canoes, that glide

Across thy breast like things of air,

-----

p. 53

Chase from thy lone and level tide,

The spell of stillness, reigning there.

Yet round this waste of wood and wave,

Unheard, unseen, a spirit lives,

That, breathing o’er each rock and cave,

To all a wild, strange aspect gives.

The thunder-riven oak, that flings

Its grisly arms athwart the sky,

A sudden, startling image brings

To the lone traveller’s kindled eye.

The gnarled and braided boughs, that show

Their dim forms in the forest shade,

Like wrestling serpents seem, and throw

Fantastic horrors through the glade.

The very echoes round this shore

Have caught a strange and gibbering tone,

For they have told the war-whoop o’er,

Till the wild chorus is their own.

Wave of the Wilderness, adieu!

Adieu ye Rocks, ye Wilds and Woods!

Roll on, thou Element of Blue,

And fill these awful solitudes!

-----

p. 54

Thou hast no tale to tell of man—

God is thy theme. Ye Sounding Caves—

Whisper of Him, whose mighty plan

Deems as a bubble all your waves!

—

LINES.

Yes! there are pleasures, that so closely tread

On suffering’s dark and melancholy train,

That scarce the throbbing heart, the aching head,

Seem conscious of the change to joy, from pain—

Not yet aroused from fear’s benumbing reign;—

Thus, when the yawning grave to health returns

Friends, for whom prayer had seemed to rise in vain,

The joy, so long delayed, half welcome dawns,

And the vexed spirit, though it kindles, mourns.

So when the bow of beauty in the skies,

Serenely arches in its native heaven,

And in its robes of many-colored dies, [sic]

Renews the promise to the Patriarchs given,—

Though stormy winds and waves are backward driven,

Still trembles Nature with her recent fears;

The agony with which her frame has striven,

In contest strange, upon her face appears,

And, though she sweetly smiles, her smiles are stained with tears.

L. M … t.

-----

Painted by Cole. Engraved by G. B. Ellis.

AMERICAN SCENERY.

-----

[p. 55]

AMERICAN SCENERY.

—

The picture by Mr Cole, of which we have given a copy under the above title, is in the possession of Daniel Wadsworth, Esq., Hartford, by whose favour we have been allowed to give it a place in the Token. It is not a view of a particular spot, but a combination of sketches from nature, taken in various parts of the country. The design of the artist appears to have been, to present in one view, the characteristic features of our mountain landscape; and, as not inappropriate to such a design, he has introduced in the distance a scene from Mr Cooper’s tale of the Last of the Mohicans. The particular point of the story referred to, is indicated by the following extracts. The lines annexed, which might be entitled Cora’s Appeal, were furnished us by a friend.

‘When the sun was seen climbing above the tops of the mountain against whose bosom the Delawares had constructed their encampment, most were seated; and as his bright rays darted from behind the outline of trees that fringed the eminence, they fell upon as grave, as attentive and as deeply interested a multitude, as was probably ever before lightened by his morning beams. Its number somewhat exceeded a thousand souls.’

‘Magua cast a look of triumph around the whole assembly, before he proceeded to the execution of his purpose. Perceiving that the men were unable to offer any resistance, he turned his

-----

p. 56

looks on her he valued most. Cora met his gaze, with an eye so calm and firm, that his resolution wavered. Then recollecting his former artifice, he raised Alice from the arms of the warrior, against whom she leaned, and beckoning Heyward to follow, he motioned for the encircling crowd to open. But Cora, instead of obeying the impulse he had expected, rushed to the feet of the patriarch; and raising her voice, exclaimed aloud;’—

Hear! old of days, hear, father! hear—

Whose ancient form, and temples, crowned

With snows of by-gone time, appear

Coeval with the hills around!

To you these Indian maidens kneel—

For mercy, justice, plead to you.

O let thine aged bosom feel

Ruth for the white man’s daughter too.

To that high peak, whose cloud-clad brow

Approaches near the Eternal’s throne,

Bid these young warriors bear me now,

Thence bid them dash me headlong down;

Or let me die in smoke and fire,

Or in yon torrent find relief,

Or perish here, by tortures dire,

Ere give me to that savage chief—

Yield me not up his victim here.

O rather rend me limb from limb—

As well the panther with the deer

May dwell in peace, as I with him!

-----

[p. 57]

THE FATED FAMILY.

—

Shortly after the close of the Revolutionary war, I visited the islands, which in a clear day, are seen so distinctly from the coast of New Hampshire. One who sees them from the shore, would take them for barren rocks rising from the sea. And such in fact they are; but they were then inhabited by a few bold and hardy men, who had little intercourse with the continent, and who did not encourage the visits of strangers by any cordiality of reception. These islands were the scene of shipwrecks, much more frequently in that day than in this, when the navigation of our coast is better understood; and as their situation made them a secure resort for those engaged in evading the revenue laws of the country, it seemed important that the inhabitants should be taught the duties of humanity to the one, and justice to the other. As I had buried the last of my family, and was desirous to spend the short remainder of my life in the service of my heavenly Master, I determined to visit

-----

p. 58

these islands in the way of my professional duty, hoping, though without enthusiasm, to do something for the benefit of the islanders, by encouraging their improvement in religion, and the duties of social life.

It was on a fine summer morning that I left the shore and stood out for the islands. They rose white and shining, like icebergs, from the dark blue sea. Our little boat sprang gaily over the waters, and in two short hours we approached the one which was distinguished from the rest by a small stone church, that stood on an elevated rock, and towered above the neighbouring buildings. As we turned the corner of the projecting rock which formed their little harbour, we saw a number of men engaged in removing the fish from their boats to the shore. When they saw us, they armed themselves with stones, and seemed determined to prevent our landing. This they would perhaps have done, but for an old man, who seemed to be superintending their labor. He reproved them with authority, though not perhaps with the dialect of a patriarch, and approaching the boat, bade me welcome. I explained to him that my desire was to preach in the church, and to instruct their children; that, as he might easily imagine, I had no interested purpose to answer, and should ask of them nothing but the privilege of doing good. After a moment’s consideration, he invited me to land, and

-----

p. 59

explained to the people the purpose with which I had come. They made no objections. Some of them even showed an interest in the plan, but soon returned to their labor, while the old man led me over the rocks into the little town.

I soon found that he had a prescriptive authority among them, and thought myself fortunate in securing his favor. As we walked slowly through the rude street, he explained to me the reason of the welcome he had given me. ‘I know nothing about priestly matters,’ said he, ‘but I have always tried to do my duty. No man can say that I have not been as honest as the times would allow. Still, there is no doubt a good deal that might be mended in all of us, and I am willing that you should try your hand. But you will have discouraging work of it, I forewarn ye. Our young men are as rough as the sea, and the children are as ignorant as cattle, though you will find them ready to mind you, if they see that you want to do them good. But there is one family here, somewhat different from the rest. It consists of a poor young girl and her brother, a wild youth, who follows the sea. Ever since she has been here, she has lived in a house of my own; and as she has often wished to see a person of your cloth, I cannot do better, than give you your lodgings in the same

-----

p. 60

house, where they live more after your inland fashion than we do.’

Thus saying, he without ceremony opened the door of a small house, and invited me to enter. A young female was sitting by the fire with her face turned from us. The old man spoke to her in a kind and respectful manner, saying, ‘Well, Miss Mary, you have often wished that there was a minister here, and here is one come at last. He seems well disposed, and as there is no other house on the island, where he could make himself content for a day, I must make bold to quarter him with you.’ I know not that I was ever more astonished, than to see a delicate and graceful girl rise when she heard the sound of his voice, and express her pleasure at seeing him. Then turning to me, she offered me her hand, and said with much sweetness, that she was happy to receive me in the house of her aged friend, which he had kindly assigned for her dwelling. Such attentions as she herself and her old companion, pointing to a deaf old woman, could afford me, they would be most happy to render; and she was confident, that as nothing but desire of doing good could have brought me thither, I should not be offended at the defects of their hospitality. Such a vision in such a place, surprised me so much, that I was almost unable to reply to her kind welcome.

-----

p. 61

The next day was the sabbath; and it rose as bright and calm, as any day that ever dawned upon the world. I saw that the boats were drawn up high upon the shore. Nothing but the low murmur of the waves broke the quiet of the islands; and the only sign of life, was the blue smoke which was gently winding upward from the humble habitations. My young companion informed me, that the islanders, though little informed with respect to religion, always respected the sabbath as a release from labor which was needed by weary man. Before the sun was high, a bell, which was used instead of a light to warn vessels by night of the danger of the islands, sent an unusual summons across the waves, and in an hour or two, boats were seen putting off from their rocky harbours, with their supplies for the little assembly at the church. I explained to them the history and purpose of Jesus Christ, who chose his apostles from an humble employment like their own; whose whole object was to make them happy in this life and another, by making them holy, just and good. I spoke with simplicity and with some effect. I wished to see no effects but such as were likely to endure, and when I could see that I had gained the attention of my little audience, my purpose was answered. I was met after the service by some of the congregation, who expressed, in rude phrase, their gratifica-

-----

p. 62

tion at hearing me talk sense and religion, and their wishes that I might do them some good. I could not help being struck with the respectful, but compassionate interest, with which my young companion was regarded; while she, in turn, had something to say to each, and she appeared so much like a superior being, with her gentle dignity of manner, that every eye, as it was turned toward her, seemed to kindle with delight.

Old as I was, I could hardly suppress my curiosity to learn the explanation of this mystery; but I felt that she had a right to take her own time to give her confidence, and I would not ask the explanation from any but herself. Meantime, she went with me from house to house, and from island to island. In every dwelling she seemed to be familiar. The children clapped their hands when they saw her, and rant o the doors to tell the inmates that she was near. I found much sickness and suffering among them; but instead of being treated as an intruder, which I expected would be the case at first, I found that I was welcomed with respect and kindness. When I gently suggested to them the consolations of religion, I found that they had heard them all before. It seemed as if an angel had preceded me to prepare my way. In these lowly mansions, I found religion kindling the innocent smiles of youth, and glowing

-----

p. 63

with holy serenity on the venerable brow of age. there were straw-built sheds from which the Samaritan would have almost turned away; in them, I found that a messenger of peace had been before me. Religion had been set before them as a principle of duty to God, and benevolence to man, and their hearts had given a quiet verdict in its favor.

Such a state of things I had never found in any other community, and the grateful testimony of all, assured me, that it was owing to her who stood modestly silent by my side. She told me that she had been early taught to derive happiness from heavenly sources, and in some of her leisure hours had read and explained the Scriptures to the sick and aged, who were unable to read for themselves. The view of its effect recommended the subject to others, and though she said she knew nothing but the first elements of Christianity, she had taken pleasure in teaching them that they were immortal, and that they had it in their own power to determine what that immortality should be.

Unequal as is the friendship of age and youth, we were almost unseparable companions; and all my acquaintance with her, served to confirm the respect, with which she had already inspired me. I often sat with her on a tomb, which is raised on a little hill, to the memory of some persons, who, in the early age of

-----

p. 64

the colony, perished by shipwreck on these islands. I found that to her everything was a subject of religious and happy contemplation. She delighted to watch the day, as it went down over the edge of the horizon to join the eternal past, and the evening star, when it began to burn in the purple radiance, as a signal for all the other fires to be lighted in the sky.

Nothing could exceed the beauty of such hours, when small sails, gilt with the soft light, were hurrying homeward, and the distant beacons were beginning to twinkle on the waters; while the very ocean seemed to share the calmness, and hushed its resounding voice to a tone as gentle and mournful as the murmurs of a dream. She loved to gaze upon the same ocean, when it was lifted and broken by the storm; when the everlasting rock of the island seemed to tremble before the battering waves, and the lightning shot its dazzling bolt to the lowest depths of the sea; while the sound of the bell, warning the seamen from the dangerous coast, was plaintive as the death angel’s voice, and at times rose higher and louder upon the wind, as if to give the alarm, that some ill-fated vessel was dashed upon the shore.

One evening when we were sitting upon this tomb, which was our favorite retreat in the summer evenings, we saw a sail at a distance, which seemed to

-----

p. 65

belong to a larger vessel, than the fishing craft that generally passed the island. The old patriarch of the community was with us, and his experienced eye at once detected it to be a ship bound for Portsmouth harbour. ‘Oh! if my poor brother should be on board,’ said Mary. ‘No, no,’ said the old man; ‘he sails in no such vessel as that, and does not often make for a harbour in the daytime.’ ‘Yes, you are right,’ she said; ‘but I live upon the home that he will abandon this infamous employment, and do something worthy of him.’ ‘Why,’ said the old man, ‘as to its being infamous, I do not exactly know; it wrongs nobody but the government, and they have not done so well by your family, that you need be uneasy about their losing a little. But I suppose the minister thinks harder of it than I do, so I won’t undertake to justify it; and yet I suppose, if he knew just how it is, he would see some excuse for your wild brother.’ ‘I hope, indeed,’ said Mary, ‘that there is some excuse for him, considering how unfortunate he has been; but I can find no justification whatever for his employment, and I would give up everything—I would labor day and night to the last breath of existence, if I could induce him to live like one of the honest young men of these islands. But this gentleman ought to know something about us, and with your leave, I will tell him our short history.’ She turned

-----