The Token, edited by Samuel Griswold Goodrich (Boston: Gray & Bowen, 1831)

-----

[presentation page]

[Transcriber’s note: Missing in my copy; the image is from the digitized database, “Sabin Americana, 1500-1926”]

-----

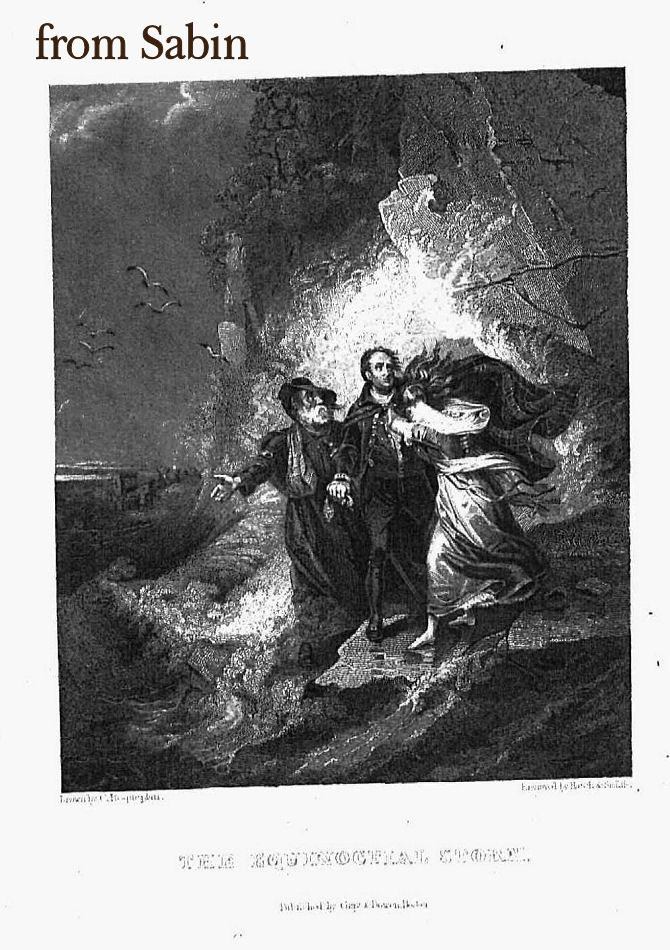

[frontispiece]

[Transcriber’s note: Missing in my copy; the image is from the digitized database, “Sabin Americana, 1500-1926”]

THE EQUINOCTIAL STORM.

-----

[engraved title page]

Engraved by E. Gallaudet.

TOKEN 1832.

-----

[title page]

A

CHRISTMAS AND NEW YEAR’S PRESENT.

EDITED BY S. G. GOODRICH.

—airy messengers have sought

These rosy realms of Fancy through,

And fairest fruits and flowers have brought,

To form an amulet for you.

And Friendship’s hand, and Love’s soft fingers,

Of these have wreathed a mystic Token;

And oh! the chain that round it lingers,

While life remains, be that unbroken.

PUBLISHED BY GRAY AND BOWEN.

MDCCCXXXII.

-----

[copyright page]

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year eighteen hundred and thirtyone, by Samuel G. Goodrich, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of Massachusetts.

HIRAM TUPPER, PRINTER.

-----

[p. 1]

PREFACE.

We need say but little for this, the fifth volume of the Token, as most of the improvements we have made in the work, are of an obvious character. These relate rather to the department of the Publishers, than to that of the Editor, and as they have been made at great expense, it is hoped they may receive due consideration from the public.

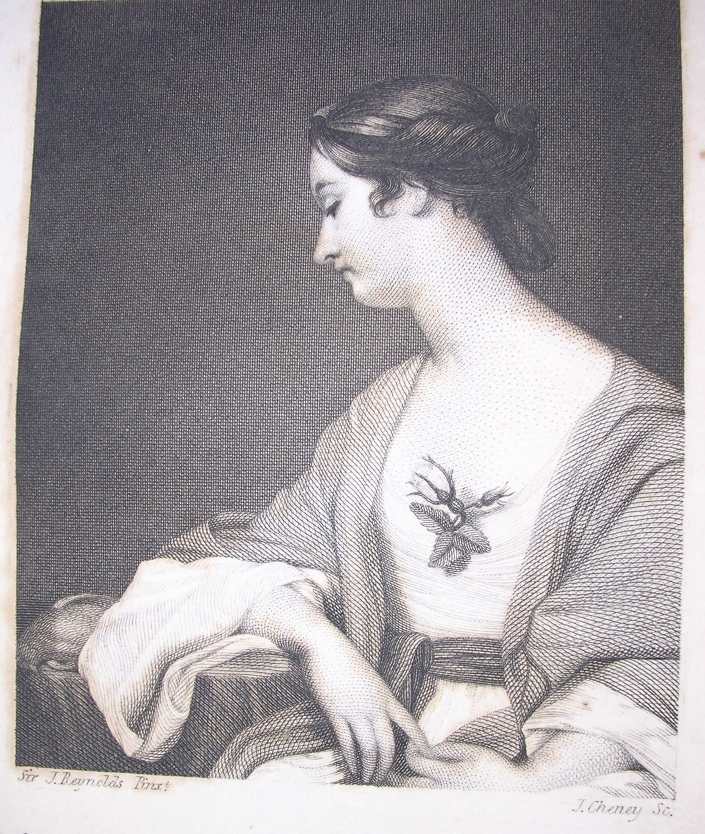

The volume is altogether more splendid than either of its predecessors, and contains twenty engravings, seventeen of which are on steel. These are all executed by our own artists, and several of them may challenge comparison with the best of the English. It will not be invidious, among so many that are excellent, to notice one, as probably superior to any engraving, hitherto produced by an American artist. This is entitled Lesbia; and was executed in London, by our young countryman, J. Cheney.

But while we thus speak of the mechanical departments of the work, we must do justice to our literary friends, who have this year laid us under peculiar obligations. They have enabled us to furnish a greater variety, as well as many more pages, than heretofore, and we trust that our readers, be they grave or gay, sad or sentimental, will each find something to suit his humor.

On the whole, we offer the book with some confidence, that it may meet a favorable reception, and that the continued encouragement of the public may strengthen us in our endeavors, each year, to surpass what we have done before.

Boston, October 1, 1831.

-----

[p. 2]

EMBELLISHMENTS.

1. Presentation, drawn by G. Harvey, and engraved by A. Hartwell. [from the copy in Sabin]

2. Fancy Title Page, the ornamental part drawn by G. Harvey, Figure and Landscape drawn by E. Gallaudet, all engraved by E. Gallaudet [central image is a version of “The Souvenir,” by Jean-Honore Fragonard]

3. Vignette, drawn and engraved, after a sketch by Stothard, by G. L. Brown … 5

4. Will he bite? painted by Fisher, engraved by E. Gallaudet … 7

5. The Fairy Isle, painted by Danby, engraved by G. G. Ellis … 19

6. The Equinoctial Storm, drawn by Roqueplan, engraved by Hatch and Smillie [from the copy in Sabin] … 37

7. Lesbia, painted by Reynolds, engraved by J. Cheney … 63

8. Young Artist, drawn by Cristall, engraved by J. J. Pease … 83

9. The Toilet, engraved by G. B. Ellis … 117

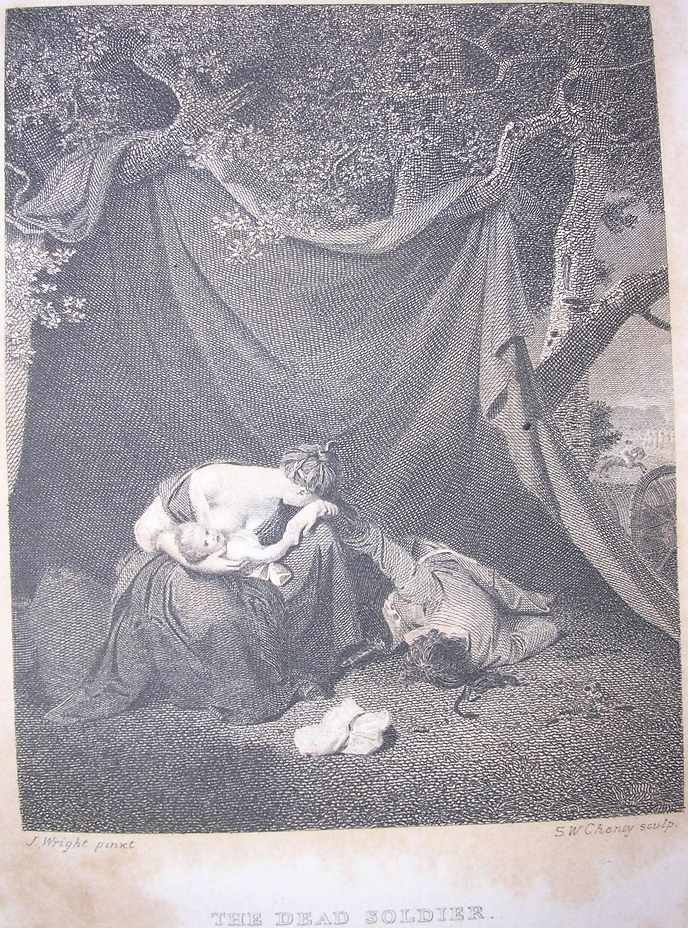

10. The Dead Soldier, painted by Wright, engraved by S. W. Cheney … 121

11. Apprehension, Drawn by Deveria, engraved by J. H. Hills … 153

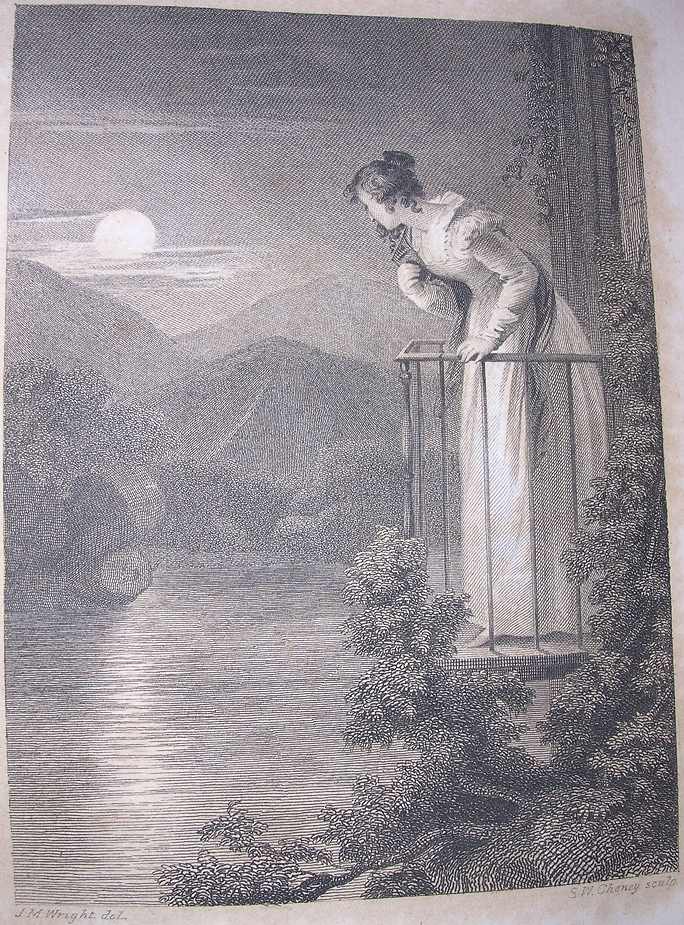

12. Invisible Serenader, engraved by S. W. Cheney … 189

13. The Freshet, painted by Fisher, engraved by G. W. Hatch … 241

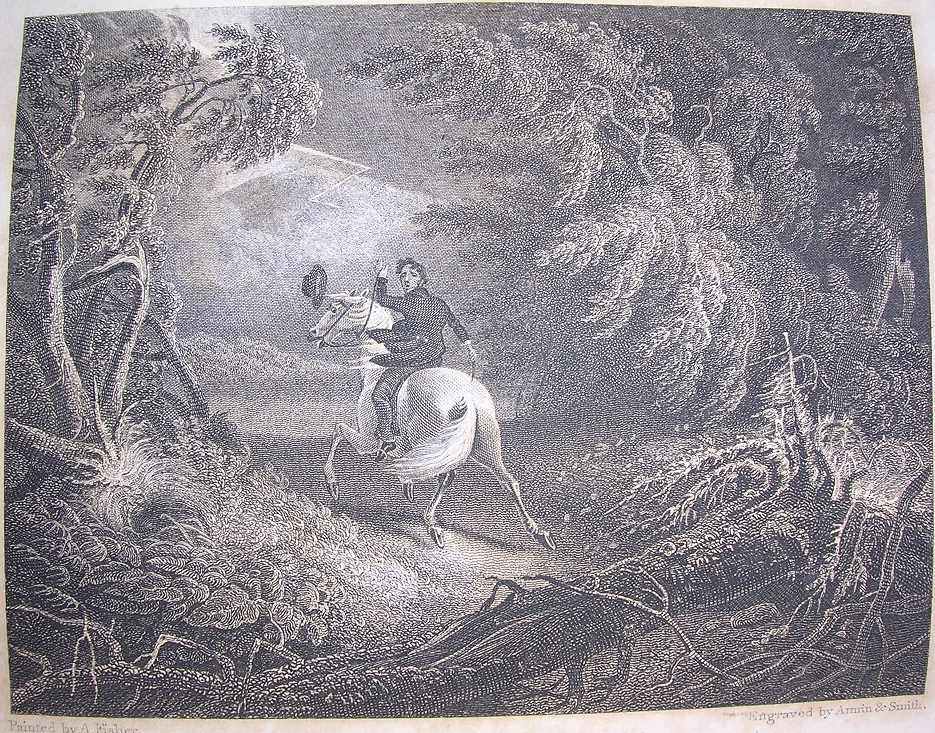

14. An Escape, painted by Fisher, engraved by Annin and Smith … 275

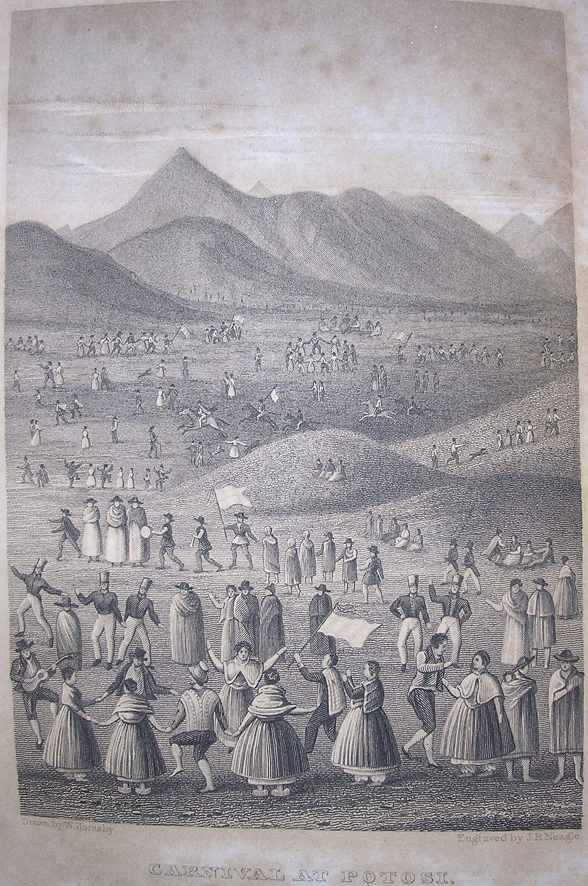

15. Carnival at Potosi, painted by W. Hornaby, engraved by J. B. Neagle … 315

16. Peasant Boy, drawn by Cristall, engraved by O. Pelton … 333

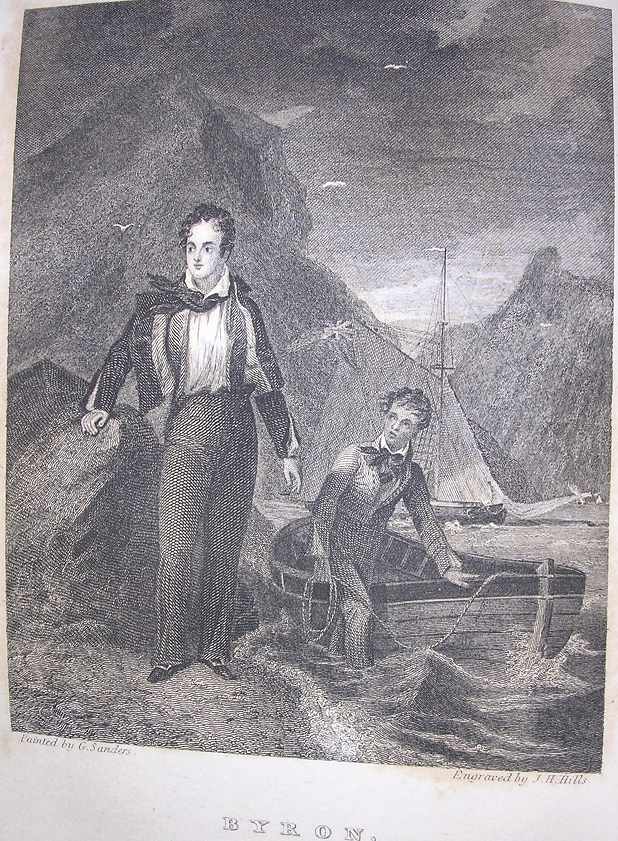

17. Byron, at the age of Nineteen, drawn by Sanders, engraved by J. H. Hills … 347

18. The Lute, engraved by O. Pelton … 373

19. The Opening of the Sixth Seal, painted by Danby, engraved by Illman and Pilbrow … 391

20. Vignette, drawn by G. L. Brown, after Northcote, engraved by A. Bowen … 392

-----

[p. 3]

CONTENTS.

Page.

To ....... [Samuel Griswold Goodrich] … 5

Will he bite? [Samuel Griswold Goodrich] … 7

What is Life? … 8

The Theology of Nature—By Orville Dewey … 9

The Surf Sprite—By S. G. Goodrich … 19

The Indian Summer [Henry Wadsworth Longfellow] … 24

The Dying Storm—By H. F. G. … 36

The Dreams of Hope—By B. B. Thatcher … 39

My Cousin Lucy—By James Hall … 41

To a Lady on her Marriage [Samuel Griswold Goodrich] … 61

The Blind Girl to her Mother [Samuel Griswold Goodrich] … 62

Lesbia—By H. F. G. [Hannah F. Gould] … 63

Scenes in a Spanish Pueblo, A Sketch—By the Author of ‘A Year in Spain’ [Alexander Slidell Mackenzie] … 64

Stanzas—By Grenville Mellen … 67

Frost—By H. F. Gould [Hannah F. Gould] … 69

The Waterfowl—By J. H. Miflin … 70

Autumn—By A. A. Locke … 71

The Wives of the Dead [Nathaniel Hawthorne] … 74

The Young Artist—By H. F. Gould [Hannah F. Gould] … 83

The Meteor [Hannah F. Gould] … 85

Weep not for the Dead—By S. G. Goodrich … 86

Returning a Stolen Ring—By Charles Sherry [John O. Sargent] … 87

My Kinsman, Major Molineux—By the Author of ‘[S]ights from a Steeple’ [Nathaniel Hawthorne] … 89

Love and Care … 116

The Toilet—By Grenville Mellen … 117

The Dead Soldier—By Mrs Sigourney [Lydia Sigourney] … 121

New England Climate … 123

-----

p. iv

The South Georgian Lark—By Mrs Sigourney [Lydia Sigourney] … 133

Touch Thy Harp—By Louisa P. Smith … 135

Fountain of Forgetfulness … 137

Philosophy—By Charles Sherry [John O. Sargent] … 138

The Bashful Man—By the Author of ‘The Vestal; or, a Tale of Pompeii’ [Thomas Gray] … 144

Apprehension—By H. F. Gould [Hannah F. Gould] … 153

The Winter Leaf—By Charles West Thomson … 154

The Fall of the Temple—By Thomas Gray, Jun. … 156

Roger Malvin’s Burial [Nathaniel Hawthorne] … 161

Legend of the Lake—By Grenville Mellen … 189

The Frozen Dove [Hannah F. Gould] … 192

The Gentle Boy [Nathaniel Hawthorne] … 193

The Freshet—By V. V. Ellis [John O. Sargent] … 241

The Minstrel—By Willis G. Clark … 243

The Valley of Vision … 246

Song of the Revolution—By Thomas Gray, Jun. … 247

Nimrod Buckskin, Esq.—By T. Flint [Timothy Flint] … 249

An Escape—From a Traveller’s Sketch Book … 275

Bloody Brook—By J. I. M’Lellan … 277

La Doncella—From the Spanish [Henry Wadsworth Longfellow] … 280

My Wife’s Novel … 281

The Carnival at Potosi … 315

Falls of the Niagara—By F. W. P. Greenwood … 317

To a Violet—By Charles Wadsworth … 332

Peasant Boy—By B. B. T. [B. B. Thatcher] … 333

A Sketch of a Blue-Stocking—By Miss Sedgwick [Catherine Maria Sedgwick] … 334

Byron, at the age of nineteen [John O. Sargent] … 347

Ruins [John O. Sargent] … 348

David Whicher—A North American Story … [John Neal] 349

The Lute [B. B. Thatcher] … 373

The Garden of Graves [John Pierpont] … 374

The Sixth Seal [Thomas Gray, jr] … 391

-----

[p. 5]

THE TOKEN.

TO .......

Yes, lady! all you say is true—

The book is rather grave than glad;

Yet if you read, perchance your view

Will meet some merry with the sad.

But be it grave, or be it gay,

I prithee let it by thee dwell,

And pardon if my idle lay

Should whisper what I might not tell.

In days of yore, ere Lowell rose,

When cotton cloth was very dear,

The people lived, as each one knows,

In other guise than we do here.

-----

p. 6

Then all were young, and mid soft bowers

They spent life’s sportive holiday;

Like very brothers loved the flowers,

The light companions of their play.

No jarring factories shook the ear,

No whizzing steam went roaring by;

But all was peace, and not a tear

E’er soiled the cheek or dimmed the eye.

Well, ONE among this happy race

Was better known than all the rest;

More wit he had, perchance more grace,

And was, by all the world, caressed.

’T is said he now is rich and old,

Though flirting at each gay cotillion,

And all the ladies, I am told,

Still love him for his half a million.

But quite unlike the one in vogue,

My Cupid was a hearty boy;

And though the maidens called him rogue,

They pressed him with more fervent joy.

They knew he wore a cruel bow,

That sent its arrows to the heart;

Yet still they loved the urchin so,

That each forgave the transient smart.

So Cupid played his merry part,

And grew at length a famous quiz,

But by and by they knew his art,

And so he masqued his roguish phiz.

With stealing step and greybeard look,

He sought the playmates of the flowers[.]

They stared at first, but when they took

The cunning joke, they laughed for hours.

So afterwards, whene’er to view

The visage came, they did not fear it,

For well those little people knew,

That Love was ever lurking near it.

G.

-----

Painted by A. Fisher. Engraved by E. Gallaudet.

WILL HE BITE?

-----

[p. 7]

WILL HE BITE?

No, boy, not one so innocent as thou,

With such youth and gentleness on his brow.

He will not harm thy little hand,

Or shrink from the touch of one so bland.

He sees in thy full and speaking eye,

Only the hues of the bending sky—

He marks in thy cheek but the wild flower’s glow,

He hears in thy voice but the glad rill’s flow.

He sees in thy step but the joyous bound

Of the mountain lamb on the slopes around.

He will not bite, for thine image brings

But semblances of familiar things—

Things that he loves in the breezy wood,

In the leafy dell, and the shouting flood.

It was deeply told, when in youth he swung

Aloft on an oak where the loud winds sung,

It was told by a whispering voice to his heart,

From a look like thine that he need not start.

’T was the wily eye, and the stealing tread,

And the knowing brow, he was taught to dread.

But thou were safe as a mountain flower,

Where the sliding snake and gaunt wolf cower—

Aye, and the proud may learn from the lay,

That Innocence hath a surer shield than they.

G.

-----

[p. 8]

WHAT IS LIFE?

What is life? Saith the sage, we are born but to die;

We live for a summer, but cannot tell why;

And the strong and the feeble, the plain and the fair,

All go in the winter we cannot tell where.

What is life? Saith the preacher, we live and we die,

Permitted to flutter, but hardly to fly;

And hereafter we live, as in this world we do

Either false and deceitful, or faithful and true.

What is life? Saith the lover, a season of bliss,

And all bliss and all life is compressed in a kiss;

To live, is to love—to be scorned, is to die—

I revive with a kiss, and expire in a sigh.

What is life? Saith the soldier, ’t is glory, my son,

The forts that are stormed, and the fields that are won;

’T is thunder and pillage, ’t is glory and strife,

With a sprinkling of beauty—and this, this is life.

What is life? Saith the miser, ’t is twenty per cent.;

’T is a mortgage foreclosed; it is premium and rent;

While his heir will asseverate, ‘Powder my wig!

’T is to dress, and to drink, and drive fast in a gig.’

What is life? Saith my dame, to be seen and admired;

To be envied, and loved, and genteely attired;

To be toasted as belle, to be honored as wife;

This, this is the end and enjoyment of life.

What is life? Saith the statesman, political rank.

Saith the merchant, oh no, it is credit in bank.

Saith the lawyer, ’t is weight with the jury and judge;

And I say, with honest old Burchill, ’t is—fudge!

-----

[p. 9]

THE THEOLOGY OF NATURE.

BY ORVILLE DEWEY.

The turf shall be my fragrant shrine;

My temple’s dome, that arch of thine;

My censer’s breath, the mountain airs;

And silent thoughts, my only prayers.

It is a bountiful creation. It is rich and full and overflowing, with the beneficence of its Maker. Less than all its plenitude and beauty might have sufficed for our wants; but less would not suffice to set forth his inexpressible goodness. When he had founded the earth, and established the mountains, and set up the great frame of nature, and implanted the germ of every useful production, it might have been enough for the necessities of man, but it was not enough for the generous kindness of his Maker; and he came forth again: he came forth with an added work, and scattered, from an unsparing hand, the bounties and delights of every clime and season. Variety and exuberance poured their stores into the lap of nature, and it was full. The earth opened its fertile bosom, and sent forth its flowers and fruits to gratify the taste; the world rung with the voice of melody to regale the ear; and hues of light were spread over the verdant earth, and the glowing clouds of eventide, and the glorious expanse of heaven, to delight the eye of man. And upon this theatre,

-----

p. 10

overspread with more than the magnificence of eastern palaces, and beneath the shining canopy of heaven, there went forth life, buoyant and strung and gifted, to enjoy it to the full; life with its untiring and matchless energies; life with its light sportings of pleasure, and its secret workings of delight; life, not bare and barren, an abstract existence, but clothed with senses, endowed with sensibility, connected by magic ties of association with the objects around it; touched with rapture at the visions that pass before it, and kindling with irrepressible aspirations after brighter visions yet to be revealed; life, full as nature is, of heavenly gifts; full of glorious capacities, of dear affections, and unbounded hopes, and thus tending, with manifest direction, to a higher and a more enduring state of beings.

But let us descend to a humbler theatre of existence, yet equally filled with proofs of the divine goodness. When we go abroad from our dwelling, in one of the bright days of summer, what a scene is presented before us! This, too, is filled with life, infinitely diversified, changing, active, intense life and pleasure. It is, I repeat, a crowded scene. It seems as if it were designed, that everything which could live, should have its happy hours of being. The spot that will not admit one kind of existence, is supplied with another. In every possible variety of situation, from the spire of grass to the lofty tree, from the plain to the mountain-top, on the hill-side and in the deep forest, in the flashing waters and the buoyant air, there are abodes, numberless, various, vast, minute, for every living thing. The very rocks are penetrated by eager claimants for their appointed spaces;

-----

p. 11

the steep and barren precipices give sure footing to the wild goat; the dark caverns echo to the footsteps of living creatures.

Descend we to a still minuter survey, aided by the microscope, and what do we find? Every clod of earth, every drop of water, every morsel of delicious fruit, is animated life. It were scarcely a stretch of imagination to conceive it may yet be proved, that the very sunbeams have life. Let not this discovery of modern philosophy, so full of the wonders of divine beneficence, disgust us. Well, indeed, that ‘man has not a microscopic eye;’ and for a plainer reason than that no-reason, that ‘man is not a fly.’ Well is it, and an added proof of goodness, that the impressions of sense are an overmatch for the teachings of philosophy. But let it not offend us, that the air we breathe, and the dust we tread upon, teem with active and glad existence.

It is a bountiful creation; and bounty demands acknowledgment; but its very silence, as to all demands upon our gratitude, seems to me more affecting, than any articulate voice of exhortation. If ‘cloven tongues of fire’ sat upon every bush and forest bough; if audible voices were borne upon every breeze, saying, ‘Give thanks! give thanks!’ however startling at first, it would not be so powerful, so eloquent, as the deep and unobtrusive silence of nature. The revolving seasons encircle us with their blessings; the fruits of the earth successively and silently spring from its bosom, and silently moulder back again to prepare for new supplies; day and night return; the ‘soft stealing hours’ roll one; mighty changes and revolutions are passing in the

-----

p. 12

abysses of the earth and the throned heights of the firmament; mighty worlds and systems are borne with speed almost like that of light, through the infinitude of space; but all is order, harmony, silence. What histories could they relate of infinite goodness; but they proclaim it not! What calls to grateful devotion are there in earth and heaven; but they speak not! No messenger stands upon the watch-towers of the creation, on hill or mountain, saying, like the Moslem priests from the minarets of their temples, ‘To prayer! to prayer!’ I am sometimes tempted to wish there were, or to wonder there are not. But so it is; there is no audible voice nor speech.

And for this cause, and for other causes, how many of Heaven’s blessings escape our notice. In how many ways is the hand of Heaven stretched out to us, and yet is unseen; in how many places does it secretly deposit its benefactions! It is as if a friend had come with soft and gentle steps to the dwelling of our want, or to the abode of our sickness, had laid down his gift, and silently turned away. And during half of our lives, the night draws her veil of darkness over the mysterious paths of Heaven’s care; and yet those paths are filled with ministering angels that wait about our defenceless pillow, and keep their watch by the couch of our repose. Yes, in night and darkness and untrodden solitudes, what histories of God’s mercy are recorded! But they are not written in human language; they are not proclaimed by mortal tongue. The dews of heavenly beneficence silently descend; its ocean rolls in its dark caverns; the

-----

p. 13

recesses of the wilderness are thronged with insects and beasts and birds, that utter no sound in the ear of man.

Full of bounty as this work of God is; silent and touching as are its appeals to gratitude, it is yet more; it is a joyous creation; and thus bears another indication of the character of its Author.

Our ideas of religion are apt to be too constrained, and, not to say too solemn, yet too exclusively of that character. Frail and sinful s we are, it is not strange that this should be the tendency of our minds, and especially so, if our minds are not familiar with this great theme. But the theology of nature teaches us a different lesson; teaches us, as the Holy Word also teaches us, to worship God, ‘with joyfulness and gladness of heart.’ The lesson is written with sunbeams upon the ever fair and youthful brow of nature. A dull and slavish piety is at war with the creation. The bright skies, the free and flowing streams, the chainless winds, the waving forests, teach us not so; and every being of nature’s ten thousand rejoicing tribes, calls us to a glad communion with it. If, indeed, the world with its tenants were smitten with universal sadness; or even if the earth were filled with dull, heavy, formal creatures, I might be obliged to think differently. but what is the fact? Is it a solemn creation that I see around me? Is it not rather, I repeat, a joyous creation? Does it not ring from side to side with notes of joy? It is not the moaning owl from her blighted tree that I commonly hear; but the glad song of the birds of day. I look abroad through the glades and forests, too, and I see not demure creatures, stalking forth in staid and dull

-----

p. 14

formality; but the prancing steed in the valley, the bounding goat upon the hills, the sportive flocks in the pasture. All about me is activity; yes, and the activity of pleasure. Swift wings fan the air around me; quick steps hurry by in their gambols; and the whole wide firmament sends forth from its viewless strings, the music of a rejoicing creation. Heaven and earth are filled, I had almost said, with a visible joy. It seems as if the Spirit that is abroad in the universe were scarcely veiled from our eyes; as if we almost saw it through its robe of light; saw an expression, more intense than any countenance can give, in the serene heavens; as if we felt a presence, nearer than that of any friend, in the beauty and fragrance and breath of summer. And the heavens—is it an illusion to think so? the heavens grow brighter, and the earth more beautiful, as we gaze upon them with the eye of devout joy and thanksgiving.

But let us take a minuter survey, and we shall find that the creation is not only filled with blessings and joys, but filled, too, with indications of the most tender and considerate care. The topics that illustrate this may be familiar, but they can never grow old or dull.

When we look abroad upon the universe, we observe, as has been said, that every portion of it, however large, or however minute, is the dwelling-place of animated life. Creatures of every rank, from the soaring eagle to the feeble insect, from the mighty elephant to the creeping reptile; creatures of every size and form and mode of existence, crowd all the regions, the spaces, the habitations of earth, of ocean, and the air. Now, there is for each one of these a path in which to go, an

-----

p. 15

element to live in, a food somewhere deposited to sustain it; but how does each one, without delay, without uncertainty, without mistake, find its proper sphere and provision? Man, with all his knowledge, could never discover it. Yet there is not a way so dark, there is not a mode of action or habit so strange or curious, there is not a provision so hidden, but the mole, the insect, the creature that lives but for an hour, goes straight to its destined end, as if the clearest reason inspired it; as if the experience of ages guided it; as if the light of heaven shone upon its unknown way. And heaven’s light does shine upon its way; and a hand of more than parental care leadeth it. A mighty Intelligence, diffused everywhere, through every clod of earth, through every tract of the inhabited waters, through every region of the populous air; a mighty Intelligence there is, like a sunbeam, guiding the children of instinct, in the darkness and in the light, in the obscure and the clear, in the height and in the depth, and abroad in every unknown and, by man, untrodden path of the living universe. A mighty Intelligence there is, but gracious and kind, present with every being, providing for every occasion, helping the feeble, and directing the strong, opening the storehouse of nature, and pointing each one to his abode, his safeguard, and his supply.

But, not only in every sphere and element of nature, does every tribe of the animal creation need an appropriate sustenance, and a peculiar set of habits, but each one needs a different covering, suited to the mode and place of its existence. With man, to provide this clothing is the work of contrivance and art; manufactories are

-----

p. 16

established at immense cost, and every year adds to the list of new inventions and new fabrics; a fair portion of all the industry in the world is employed in these labors. But while man, because he is endowed with skill to manufacture his own apparel, and in order that he may live in all climates, and possess the world for his inheritance, is left to provide for himself, as his exigences require, observe how admirably nature has taken care for all its irrational children. ‘They toil not; they spin not;’ and yet man, in all the pride of regal pomp, in all the splendor of opulence, in all the multiplicity of his inventions, is not arrayed like one of these; and is obliged, for his goodliest adorning and attire, for his down and his furs, for his ermine and his waving plumes, to resort to the humble creature that prowls in the wilderness, or makes his habitation among the rude and unsightly rocks, or steals forth from the ices of the Pole. Wherever these tenants of nature wander, on the mountains that are covered with eternal snow, or beneath the blazing firmament of the Zone; whether they cut the liquid stream, or try the courses of heaven; whether they walk forth in their might and shake the earth with their footsteps, or creep among the silent reeds and by the still water-courses; whether they paw with the war-horse in the valley, or weave their gossamer web that is shaken in the breeze; behold, each one hath his appropriate vesture, such as all human art could not form, and cannot imitate. Let this art be tasked to the utmost, and it cannot weave their gossamer web that is shaken in the breeze; behold, each one hath his appropriate vesture, such as all human art could not form, and cannot imitate. Let this art be tasked to the utmost, and it cannot weave the fine fabric that clothes the back of the spider, and which, we may add, under the magnifying glass is more beautiful

-----

p. 17

than all that the richest dyes can stamp upon our most exquisitely-wrought fabrics; let this art be tasked to the utmost, and it cannot make a feather; it cannot, in its choicest soil and climate, cause anything to grow like the furs that are nourished amidst the frozen latitudes of the North; it cannot form such a coat of mail, as guards the leviathan of the deep.

And why, let it be asked, is all this, and from whence does it proceed? Why does that which in animals of the warm latitudes is a thin covering of hair, in the cold regions f the earth thicken to a warm clothing of fur; and why does this, in the severest seasons, become longer and warmer to meet the exigency?—a rule so invariable that the dealers in fur depend upon it with perfect confidence. Could the sending of an additional garment by a kind parent, to a child, destitute and exposed, more strikingly indicate a considerate and tender care? And why, also, do the scales of the fish, so perfectly adapted to his element, become in the bird, the most delicate and buoyant plumage?—a clothing so fit and beautiful, that nothing more appropriate could be given to creatures that dwell in the air, and sing among the branches. It is unlike the fur of animals, which it most resembles, in being cooler, as well as that it is fitted for flight; and yet when the sun has withdrawn his power, and the chilling shades come on, it is capable of being gathered and wrapped more closely for a mantle in the night season. Here is united in one dress, lightness as well as beauty, strength and buoyancy, adaptation for every climate and element, apparel for the day, and clothing for the night.

-----

p. 18

Well did the sacred Teacher, so remarkable for his frequent allusions to nature, say, ‘Consider the ravens; behold the fowls of the air; look abroad upon the wonders of the creation; consider these things, O man! and be wise, be faithful, and confiding.’

Confide in God. Trust in a Being, whose inspection and care nothing can escape; whose goodness created wants but to supply them; whose bounty hath no law but that of infinite diffusion. Believe, that He who heareth the young ravens when they cry, will hear the voice of thy prayer. Believe, that he who hath a providence over the limbs and senses, even the weakest and lowest of them, hath a providence over the mind. Believe, that he who guideth the way of instinct; who guideth the flight of the bird in his migration from clime to clime, will guide the soul in its untried and unknown way. ‘There is a Power,’ says a poet of our own, in an admired passage;—

‘There is a power, whose care

Teaches thy way along that pathless coast,—

The desert and illimitable air,—

Lone wandering, but not lost.’

And how reasonable, as well as beautiful, is the inference!

‘He, who, from zone to zone,

Guides through the boundless sky thy certain flight,

In the long way that I must tread alone,

Will guide my steps aright.’

-----

Painted by F. Danby ARA. Engraved by Geo. B. Ellis.

THE FAIRY ISLE.

-----

[p. 19]

THE SURF SPRITE.

BY S. G. GOODRICH.

I.

In the far off sea there is many a sprite,

Who rests by day, but awakes at night.

In hidden caves where monsters creep,

When the sun is high, these spectres sleep.

From the glance of noon, they shrink with dread,

And hide mid the bones of the ghastly dead.

Where the surf is hushed, and the light is dull,

In the hollow tube and the whitened skull,

They crouch in fear or in whispers wail,

For the lingering night, and the coming gale.

But at eventide, when the shore is dim,

And bubbling wreaths with the billows swim,

They rise on the wing of the freshened breeze,

And flit with the wind o’er the rolling seas.

At summer eve, as I sat on the cliff,

I marked a shape like a dusky skiff,

That skimmed the brine, toward the rocky shore—

I heard a voice in the surge’s roar—

I saw a form in the flashing spray,

And white arms beckoned me away.

II.

Away o’er the tide we went together,

Through shade and mist and stormy weather.

-----

p. 20

Away, away, o’er the lonely water,

On wings of thought like shadows we flew,

Nor paused mid scenes of wreck and slaughter,

That came from the blackened waves to view.

The staggering ship to the gale we left,

The drifting corse and the vacant boat,

The ghastly swimmer all hope bereft—

We left them there on the sea to float!

Through mist and shade and stormy weather,

That night we went to the icy Pole,

And there on the rocks we stood together,

And saw the ocean before us roll.

No moon shone down on the hermit sea,

No cheering beacon illumed the shore,

No ship on the water, no light on the lea,

No sound in the ear but the billow’s roar.

But the wave was bright, as if lit with pearls,

And fearful things on its bosom payed;

Huge crakens circled in foamy whirls,

As if the deep for their sport was made,

Or mighty whales through the crystal dashed,

And upward sent the far glittering spray,

Till the darkened sky with the radiance flashed,

And pictured in glory the wild array.

III.

Hast thou seen the deep in the moonlight beam,

Its wave like a maiden’s bosom swelling?

Hast thou seen the stars in the water’s gleam,

As if its depths were their holy dwelling?

-----

p. 21

We met more beautiful scenes that night,

As we slid along in our spirit-car,

For we crossed the South Sea, and, ere the light,

We doubled Cape Horn on a shooting star.

In our way we stooped, o’er a moonlit isle,

Which the fairies had built in the lonely sea,

And the surf spirit’s brow was bent with a smile,

As we gazed through the mist on their revelry.

The ripples that swept to the pebbly shore,

O’er shells of purple in wantonness played,

And the whispering zephyrs sweet odors bore,

From roses that bloomed amid silence and shade.

In winding grottos, with gems all bright,

Soft music trembled from harps unseen,

And fair forms glided on wings of light,

Mid forests of fragrance, and vallies of green.

There were voices of gladness the heart to beguile,

And glances of beauty too fond to be true—

For the surf sprite shrieked, and the Fairy Isle,

By the breath of the tempest was swept from our view.

Then the howling gale o’er the billows rushed,

And trampled the sea in its march of wrath;

From stooping clouds the red lightnings gushed,

And thunders moved in their blazing path.

’T was a fearful night, but my shadowy guide

Had a voice of glee as we rode on the gale,

For we saw afar a ship on the tide,

With a bounding course and a fearless sail.

In darkness it came, like a storm-sent bird,

But another ship it met on the wave—

-----

p. 22

A shock—a shout—but no more we heard,

For they both went down to their ocean grave!

We paused on the misty wing of the storm,

As a ruddy flash lit the face of the deep,

And far in its bosom full many a form

Was swinging down to its silent sleep.

Another flash! and they seemed to rest,

In scattered groups, on the floor of the tide—

The lover and loved, they were breast to breast,

The mother and babe, they were side by side.

The leaping waves clapped their hands in joy,

And gleams of gold with the waters flowed,

But the peace of the sleepers knew no alloy,

For all was hushed in their lone abode.

IV.

On, on, like midnight visions, we passed,

The storm above, and the surge below,

And shrieking forms swept by on the blast,

Like demons speeding on errands of woe.

My spirit sank, for aloft in the cloud,

A star-set flag on the whirlwind flew,

And I knew that the billow must be the shroud

Of the noble ship and her gallant crew.

Her side was striped with a belt of white,

And twenty guns from each battery frowned,

But the lightning came in a sheet of flame,

And the towering sails in its folds were wound.

Vain, vain was the shout, that in battle rout,

Had run as a knell in the ear of the foe,

-----

p. 23

For the bursting deck was heaved from the wreck,

And the sky was bathed in the awful glow!

The ocean shook to its oozy bed,

As the swelling sound to the canopy went,

And a thousand fires like meteors shed

Their light on the tossing element.

A moment they gleamed, then sank in the foam,

And darkness swept over the gorgeous glare—

They lighted the mariners down to their home,

And left them all sleeping in stillness there!

V.

The storm is hushed, and my vision is o’er,

The surf sprite changed to a foamy wreath,

The night is deepened along the shore,

And I thread my way o’er the dusky heath.

But often again I shall go to that cliff,

And seek for her form on the flashing tide,

For I know she will come in her airy skiff,

And over the sea we shall swiftly ride.

-----

[p. 24]

THE INDIAN SUMMER.

Farewell!—as soon as I am dead,

Come all, and watch one night about my hearse;

Bring each a mournful story and a tear,

To offer at it, when I go to earth.

With flattering ivy clasp my coffin round;

Write on my brow my fortune.

The Maid’s Tragedy.

In the melancholy month of October, when the variegated tints of the autumnal landscape begin to fade away into the pale and sickly hue of death, a few soft, delicious days, called the Indian Summer, steal in \upon the close of the year, and, like a second spring, breathe a balm round the departing season, and light up with a smile the pallid features of the dying year. They resemble those calm and lucid intervals, which sometimes precede the last hour of slow decline; mantling the cheek with the glow of health; breathing tranquillity around the drooping heart; and, though seeming to indicate, that the fountains of life are springing out afresh, are but the sad and sure precursors of dissolution; the last earthly sabbath

Of a spirit who longs for a purer day,

And is ready to wing her flight away.

I was once making a tour, at this season of the year, in the interior of New England. The rays of the setting sun glanced from the windows and shingle roofs of the little farmhouses scattered over the landscape; and the

-----

p. 25

soft hues of declining day were gradually spreading over the scene. The harvest had already been gathered in; and I could hear the indistinct sound of the flail from the distant threshing floor. Now and then a white cloud floated before the sun, and its long shadow swept across the stubble field and climbed the neighboring hill. The tap of a solitary woodpecker echoed from the orchard; and at intervals a hollow gust passed like a voice amid the trees, scattering the colored leaves, and shaking down the ruddy apples.

As I rode slowly along, I approached a neat farmhouse, that stood upon the slope of a gentle hill. There was an air of plenty about it, that bespoke it the residence of one of the better class of farmers. Beyond it, the spire of a village church rose from a clump of trees; and to the westward lay a long cultivated valley, with a rivulet winding like a strip of silver through it, and bounded on the opposite side by a chain of high, rugged mountains.

A number of horses stood tied to a rail in front of the house, and there was a crowd of peasants in their best attire at the doors and windows. I saw at once, by the sadness of every countenance, and the half-audible tones of voice in which they addressed each other, that they were assembled to perform the last pious duties of the living to the dead. Some poor child of dust was to be consigned to its long home. I alighted, and entered the house. I feared that I might be an intruder upon that scene of grief; but a feeling of painful and melancholy curiosity prompted me on. The house was filled with country people from the neighboring villages, seated around with that silent decorum, which in the country

-----

p. 26

is always observed on such occasions. I passed through the crowd to the chamber, in which, according to the custom of New England, the body of the deceased was laid out in all the appalling habiliments of the grave. The coffin was placed upon a table in the middle of the room. Several of the villagers were gazing upon the corpse, and as they turned away, speaking to each other in whispers of the ravages of death, I drew near, and looked for a moment upon those sad remains of humanity. The countenance was calm and beautiful, and the pallid lips apart, as if the last sigh had just left them. On the coffin-plate I read the name and age of the deceased. She had been cut off in the bloom of life.

As I gazed upon the features of death before me, my heart rebuked me. There was something cold and heartless, in thus gazing idly upon the relics of one whom I had not known in life; and I turned away with an emotion of more than sorrow. I look upon the last remains of a friend, as something that death has hallowed. The dust of one, whom I had loved in life, should be loved in death. I should feel, that I were doing violence to the tender sympathies of affection, in thus exposing the relics of a friend to the idle curiosity of the world; for the world could never feel the emotion that harrowed up my soul, nor taste the bitterness, with which my heart was running over.

At length the village clergyman arrived, and the funeral procession moved towards the church. The mother of the deceased followed the bier, supported by the clergyman, who tried in vain to administer consolation to a broken heart. She gave way to the

-----

p. 27

violence of her grief, and wept aloud. Beside her walked a young man, who seemed to struggle with his sorrow, and strove to hide from the world what was passing in his bosom.

The church stood upon the outskirts of the village, and a few old trees threw their soft, religious shade around its portals. The tower was old and dilapidated; and the occasional toll of its bell, as it swung solemnly along the landscape, deepened the soft melancholy of the scene.

I followed the funeral train at a distance, and entered the church. The bier was placed at the head of the principal aisle, and after a moment’s pause, the clergyman arose, and commenced the funeral service with prayer. It was simple and impressive; and, as the good man prayed, his countenance glowed with pure and fervent piety. He said there was a rest for the people of God, where all tears should be wiped from their eyes, and where there should be no more sorrow nor care. A hymn was then sung, appropriate to the occasion. It was one from the writings of Dr Watts, beginning,

Unveil thy bosom, faithful tomb;

Take this new treasure to thy trust,

And give these sacred relics room

To slumber in the silent dust.

No pain, no grief, no anxious fear,

Invade thy bounds; no mortal woes

Can reach the peaceful sleeper here,

While angels watch its soft repose.

-----

p. 28

The pauses were interrupted by the sobs of the mother; it was touching in the extreme. When it ceased, the aged pastor again arose and addressed his simple audience. Several times his voice faltered with emotion. The deceased had been a favorite disciple since her residence in the village, and he had watched over her slow decay with all the tender solicitude of a father. As he spoke of her gentle nature; of her patience in sickness; of her unrepining approach to the grave; of the bitterness of death; and of the darkness and silence of the narrow house, the younger part of the audience were moved to tears. Most of them had known her in life, and could repeat some little history of her kindness and benevolence. She had visited the cottages of the poor; she had soothed the couch of pain; she had wiped away the mourner’s tears!

When the funeral service was finished, the procession again formed, and moved towards the graveyard. It was a sunny spot, upon a gentle hill, where one solitary beech-tree threw its shade upon a few mouldering tombstones. They were the last mementos [sic] of the early settlers and patriarchs of the neighborhood, and were overgrown with grass and branches of the wild rose. Beside them there was an open grave. The bier was placed upon its brink, and the coffin slowly and carefully let down into it. The mother came to take her last farewell. It was a scene of heart-rending grief. She paused, and gazed wistfully into the grave; her heart was buried there. At length she tore herself away in agony; and, as she passed from the spot, I could read in

-----

p. 29

her countenance, that the strongest tie, which held her to the world, had given way.

The rest of the procession passed in order by the grave, and each cast into it some slight token of affection, a sprig of rosemary, or some other sweet-scented herb. I watched the mournful procession returning along the dusty road, and, when it finally disappeared behind the woodland, I found myself alone in the graveyard. I sat down upon a moss-grown stone, and fell into a train of melancholy thoughts. The gray of twilight overshadowed the scene. The wind rushed by in hollow gusts, sighed in the long grass of the grave, and swept the rustling leaves in eddies around me. Side by side, beneath me, slept the hoary head of age, and the blighted heart of youth; mortality, which had long since mouldered back to dust, and that from which the spirit had just departed. I scraped away the moss and grass from the tombstone, on which I sat, and endeavored to decipher the inscription. The name was entirely blotted out, and the rude ornaments were mouldering away. Beside it was the grave that had just closed over its tenant. What a theme for meditation! The grave that had been closed for years; and that upon which the mark of the spade was still visible! One whose very name was forgotten, and whose last earthly record had crumbled and wasted away; and one over whom the grass had not yet grown, nor the shadows of night descended!

When I returned to the village, I learned the history of the deceased. It was simple, but to me it was affecting. The mother had been left a widow with

-----

p. 30

two children, a son and a daughter. The son had been too soon exposed to the temptations of the world; had become dissolute, and was carried away by the frenzy of intemperance. This almost broke her heart, but it could not alienate her affection. There is something so patient and so enduring in the love of a mother! it is so kind to us; so consoling; so forgiving! the world deceives us, but that deceives us not; friends forsake us, but that forsakes us not; we may wound it, we may abandon it, we may forget it; but it will never wound, nor abandon, nor forget us!

The daughter was delicate and feeble. She sickened in her mother’s arms, and fell into a slow decline. Her brother’s ingratitude had stricken her too. Those who have watched the progress of slow and wasting decline, may recollect how fondly the sufferer will cling to some favorite wish, whose gratification she thinks may strengthen her wasted frame, and which, though we are persuaded it will be useless to grant, we feel it cruelty to deny. With this hope, she had longed for the calm retirement of the country, and had come with her mother into the bosom of these solitudes, to breathe their pure, exhilarating air, and to forget, in the calm of rural life, the cares that seemed to hurry on the progress of the disease. There is a quiet charm in rural occupations, which soothes and tranquillizes the soul; and the invalid, that is heartsick with the noise of the city, retires to the shades of country life, finds the hope of existence renewed, and something taken away from the bitterness of death. When the poor girl saw her young friends around her in the bloom of health and the hilarity of

-----

p. 31

youth, and she alone drooping and sickly, she felt that it was hard to die. But in the shades of the country, the gaiety of the world was forgotten. No earthly desire intruded to overshadow the soft serenity of her soul; and, when the last hope of life forsook her, a voice seemed to whisper, that in the sleep of death no cares intruded, and that they were blessed who died in the Lord.

The summer passed away in rural occupations, and the simple pastimes of country life. She was regular in her devotions at the village church on Sundays, and after the service, would visit the cottages of the poor with her mother, or stroll along the woodland, and listen to the song of the birds, and the melancholy ripple of the brook. At such times she would speak touchingly of her own fate, and look up with tears into her mother’s face. Then her thoughts would wander back to earlier days—to her young companions—to her brother. When she spoke of him, she wept as though her heart would break. They were nearly of the same age, had been educated together, and had loved each other with all the tenderness of brotherly love. There was something terrible in the idea that he had forgotten her, just as she was dropping into the grave. But there are sometimes alienations of the heart, which even the dark anticipations fo death cannot change.

At length the autumn came, that sober season, whose very beauty reminds us of dissolution and decay. The summer birds had flown, the leaf changed its hue, and the wind rustled mournfully amid the trees. As the season advanced, the health of the invalid gradually

-----

p. 32

declined. The lamp of life was nearly exhausted. Her rambles became confined to a little garden, where she would sometimes stroll out of a morning to gather flowers for her window. The fresh morning air seemed to revive her; but, towards the close of day, the hectic would flush her cheek, and but too plainly indicate that there was no longer any hope of life.

The mother watched her dying child with an anguish, that none but a mother’s heart can feel. She would sit, and gaze wistfully upon her, as she slept, and pour out her soul in prayer, that this last solace of her declining years might yet be spared her. But the days of her child were numbered. She had become calm and resigned, and her soul seemed to be springing up to a pure and heavenly joy. Religion had irradiated the gloom of the sick chamber, and brightened the pathway of the tomb. Death had no longer a sting; nor the grave a victory.

The soft, delightful days of the Indian Summer succeeded, smiling on the year’s decline. The poor sick girl was too weak to leave her chamber; but she would sit for hours together at the open window, and enjoy the calm of the autumnal landscape. One evening she was thus seated, watching the setting sun, as it sank slowly behind the blue hills, dying in crimson the clouds of the western sky, and tinging the air with soft, purple light. Her feelings had taken a calm from the quiet of the scene; and she thought how sweet it were that life should close, like the close of an autumn day, and the clouds of death catch the radiance of a glorious and eternal morning.

-----

p. 33

A little bird, that had been the companion of her sickness, was fluttering in its cage beside her, and singing with a merry heart from its wicker prison. She listened a moment to its song, with a feeling of tenderness, and sighed. ‘Thou hast cheered my sick chamber with thy cheerful voice,’ said she, ‘and hast shared with me my long captivity. I shall soon be free, and I will not leave thee here a prisoner.’ As she spoke she opened the door of the cage; the bird darted forth from the window, balanced itself a moment on its wings, as if to say farewell, and then rose up into the sky with a song of delight.

As she watched her little favorite floating upwards in the soft evening air, and growing smaller and smaller, until it diminished to a little speck in the blue heaven, her attention was arrested by the sound of a horse’s hoofs. A moment after, the rider dismounted at the door. When she beheld him, her cheek became suddenly flushed, and then turned deadly pale again. She started up, and rushed towards the door, but her strength failed her; she faltered, and sunk into her mother’s arms in a swoon. Almost at the same moment the door opened, and her brother entered the room.

The ties of nature had been loosened, but were too strong to be broken. The rebukes of conscience had risen above the song of the revel, and the maddening glee of drunkenness. Haunted by fearful phantoms, and full of mental terrors, he had hurried away from the scenes of debauch, hoping to atone for his errors, by future care and solicitude. His mother embraced

-----

p. 34

him with all the tender yearnings of a mother’s heart. Sorrow had chastened every reproachful feeling; silenced every sentiment of reproof. She had already forgotten all past unkindness.

In the mean time, the poor invalid was carried to bed insensible; and an hour passed before signs of returning life appeared. A small taper threw its pale and tremulous rays round the chamber, and her brother sat by her bed-side, silently and anxiously watching her cold, inanimate features. At length a slight color flushed her cheek; her lips moved, as if she were endeavoring to articulate something; then she sighed deeply, and languidly opened her eyes, as if awakening from a deep sleep. Her mother was bending over her; she threw her arms about her neck and kissed her. ‘Mother,’ said she, in a soft and almost inaudible voice, ‘I have had such a dream!—I thought that George had come back again; and that we were happy; and that I should not die—not yet! But no, it was not a dream,’ continued she, raising her head from the pillow, and gazing wistfully about the room. ‘He has come back again; and we are happy; and, oh! other, must I die!’ Here she fell back upon her pillow, and, covering her face with both hands, burst into tears.

Her brother, who sat by the bed-side hidden by the curtain, could no longer withstand the violence of his emotions. He caught her in his arms, and kissed her tears away. She unclosed her eyes, smiled, and faintly articulated ‘dear George;’ the rest died upon her lips. It was nature’s last effort. She turned her eyes from

-----

p. 35

him to her mother; then back; then to her mother again; her lips moved; an ashy hue spread over her countenance; and she expired with a sigh.

Such was the history of the deceased, as I gathered it from one of the villagers. I continued my journey the next morning, and passed by the graveyard. The sun shone softly upon it, and the dew glistened upon the turf. It seemed to me an image of the morning of that eternal day, when this corruptible shall put on incorruption, and this mortal shall put on immortality.

L.

-----

[p. 36]

THE DYING STORM.

I am feeble, pale, and weary,

And my wings are nearly furled;

I have caused a scene so dreary

That I long to quit the world.

With bitterness I ’m thinking

On the evil I have done,

And to my caverns sinking

From the coming of the sun!

The heart of man will sicken

In that pure and holy light,

When he sees his hopes are stricken

With an everlasting blight.

For, widely, in my madness,

Have I poured abroad my wrath;

And, changing joy to sadness,

Scattered ruins on my path!

Earth shuddered at my motion,

And my power in silence owns;

But the deep and troubled ocean

O’er my deeds of horror moans.

I have sunk the brightest treasure;

I ’ve destroyed the fairest form;

I have sadly filled my measure,

And am now a dying storm!

H. F. G.

-----

[p. 37]

THE EQUINOCTIAL STORM.

The description of the storm, and the perils of Sir Arthur Wardour and his daughter, in the ‘Antiquary,’ has been always deemed one of the finest passages in Scott’s Novels. In presenting our readers with an engraving, illustrative of the most interesting part of this scene, we cannot do better than quote the particular words to which the picture refers.

‘It was indeed a dreadful evening. The howling of the storm mingled with the shrieks of the sea-fowl, and sounded like the dirge of the three devoted beings, who, pent between two of the most magnificent, yet most dreadful objects of nature—a raging tide and an insurmountable precipice—toiled along their painful and dangerous path, often lashed by the spray of some giant billow, which threw itself higher on the beach than those which had preceded it. Each minute did their enemy gain ground perceptibly upon them. Still, however, loth to relinquish the last hopes of life, they bent their eyes on the black rock pointed out by Ochiltree. It was yet distinctly visible among the breakers, and continued to be so, until they came to a turn in the precarious path where an intervening projection of rock hid it from their sight. Deprived of the view of the beacon on which they had relied, here then they experienced the double agony of terror and suspense. They struggled forward however; but, when they arrived at the point from which they ought to have seen the crag,

-----

p. 38

it was no longer visible. The signal of safety was lost among a thousand white breakers, which, dashing upon the point of the promontory, rose in prodigious sheets of snowy foam as high as the mast of a first-rate man-of-war, against the dark brow of the precipice.

The countenance of the old man fell. Isabella gave a faint shriek, and, “God have mercy upon us!” which her guide solemnly uttered, was piteously echoed by Sir Arthur—“My child! my child!—to die such a death!”—

“My father! my dear father!” his daughter exclaimed, clinging to him, “and you too, who have lost your own life in endeavoring to save ours!”—

“That ’s not worth the counting,” said the old man. “I hae lived to be weary o’ life; and here or yonder—at the back o’ a dyke, in a wreath o’ snaw, or in the wame o’ a wave, what signifies how the auld gaberlunzie dies!”

“Good man,” said Sir Arthur, “can you think of nothing?—of no help?—I ’ll make you rich—I ’ll give you a farm—I ’ll—[”]

“Our riches will be soon equal,” said the beggar, looking out upon the strife of the waters—“they are sae already; for I hae nae land, and you would give your fair bounds and barony for a square yard of rock that would be dry for twal hours.”

While they exchanged these words, they paused upon the highest ledge of rock to which they could attain. Here then they were to await the sure though slow progress of the raging element[.]’

-----

[p. 39]

THE DREAMS OF HOPE.

BY B. B. THATCHER.

Far out upon the desert sea,

When winds and surges roar,

And many a deep cloud veils the sky

And the dim ocean o’er;

Sweet is the weary wanderer’s sleep,

Long tossed upon that main,

Who, morn and eve, hath watched and wept

For his native land in vain.

What, then, though the proud ship tremble

With the proud waves’ angry dash;

And aloft on the rocking foam-crests,

Fiercely the storm-fires flash!

For gloriously, oh! gloriously,

Of his own old mountain-shore

He dreams; and the airs of his childhood

Breathe round him as of yore.

So slumbereth on, mid wind and wave,

In sorrow and in strife,

The immortal pilgrim spirit

On the weary sea of life.

Hopes! burning hopes! these are its dreams,

These are its rich repose;

-----

p. 40

Come they alone at midnight hour,

Or at dusky even-close?

Come they alone to him that sleeps

On the ocean’s rolling foam?

Or to those who wait to welcome him

Again to his dear home?

Oh no! oh no! visions arise,

Even now, of the bright clime,

Where never sounds an echo

Of the dashing surge of time:

Far off, far off, amid the gloom

Over that strand divine,

I see the star of Bethlehem

Like a mariner’s beacon shine:

I feel the balm of odors sweet

Breathing from that dim shore,

While thoughts of Heaven, like birds from land,

Fly forth, unseen before.

I hear with my spirit’s ear the gush

Of the rills of holy ground;

And low love-tones of angels

From the starry skies around:—

In vain! in vain!—when shall my bark

E’er cross this stormy sea!

When, when shall hopes that pass not by,

Come out, O God, from thee!

-----

[p. 41]

MY COUSIN LUCY.

BY JAMES HALL.

It has been well said, that the memory never loses an impression, that has once been made upon it. The lines may be obscured for a time, as an inscription is defaced by rust, but they are never obliterated; they may be buried under a crowd of other recollections, but there are times when these roll away, as the mist rises from the valley, and the whole picture stands disclosed, in its original integrity. Impressions made in childhood are the most vivid; years may pass, and other remembrances be gathered in, but those that lie deepest are longest retained, and most fondly cherished. Other events touch the heart and pass off, without leaving a trace, but these strike in, engraft themselves, and become a part of our nature. Such, at least, has been my experience. I have lived a busy, and I trust not an useless life; I have seen much of the world, my feelings and passions have been excited, and my attention powerfully fixed, by events of deep interest; but none stand recorded in the same bold, indelible characters which mark some of the remembrances of my childhood.

Not far from my father’s residence, there was a school house. It was a small log building, such as we often see in new countries, and stood in a grove, on an eminence near the road. Whether chance, or taste, or convenience, dictated the choice of the spot, I cannot tell; but it

-----

p. 42

always struck me as being not only well adapted to the purpose, to which it was appropriated, but remarkably picturesque. The grove contained not more than an acre or two of ground, but the trees were large spreading oaks, that I have seldom seen surpassed in size or beauty; for every observer of nature will agree with me, that trees, even of the same species, differ in appearance as widely as human beings. In every grove, the vegetation has some distinguishing characteristic, just as all the inhabitants of a village have some trait in common. The trees are stinted, or luxuriant, spreading or tall, majestic or beautiful; or else they are vulgar, common-place trees, as devoid of interest, as the unmeaning people whom we meet with every day. I never see a great oak standing by the road side, without observing its peculiarities. Some are round and portly, some tall and spindling; some aspire, and others grovel; one has a gracefully rounded outline, and another a rugged, irregular shape. Here you may behold one waving its head with a courtly bend, and there you may see another tossing its great arms up and down like some angular, long limbed, gigantic booby. Trees, too, have their diseases, their accidents, and their adventures. They are torn by the wind, shattered by the lightning, and nipped by the frost; and while some of them have in their youth the aspect of sallow and dyspeptic invalids, others flourish in a green old age; and whether standing singly in the field, or crowded together in the forest, whether embraced by ivy, clothed with moss, or hung with misletoe, [sic] they always attract attention, by the peculiarities which they derive from these, and other incidents.

-----

p. 43

Our schoolhouse oaks were of the majestic kind. They had braved the elements for at least a century, and seemed to be still in the vigor of life. Their great, dark trunks were covered with moss, and their immense branches interlocking far above the ground, shadowed it with a canopy, that not a sunbeam could penetrate. The soil was trodden hard and smooth by the school-boys, and covered with a short greensward, over which the wind swept so freely, as to carry away all the fallen leaves.

Here we played, and wrestled, and ran races; here, in hot weather, the master, forsaking the schoolhouse, disposed his noisy pupils in groups among the trees; here the rustic orator harrangued his patriotic fellow-citizens on the anniversary of Independence; and here the itinerant preacher addressed the neighbors on the Sabbath. On occasions like the latter, our grove became as gay as a parterre. The bonnets, and ribbons, and calicoes, were as numerous, and many colored, as the flowers of the field. The farmers and their families generally came to the preaching on horseback; and it was a fortunate animal that bore a lighter burthen than two adults, and a brace of children. The young women rode behind their brothers or sweethearts, or in default of such attendants, mounted sociably in pairs, the best rider taking the saddle and holding the reins, as smart girls are always willing enough to do. It was a goodly sight to see the horses hitched to the trees in every direction, shewing off their sleek hides, and well-combed manes to the best advantage, and decked with new saddles and gaudy saddle-cloths, and fine riding skirts,

-----

p. 44

that were never exposed to the weather or the eye, except on Sundays and holidays. Then the people, before the sermon began, sitting in groups, or strolling in little companies, looked so gay and so happy, that Sunday seemed to be to them, not merely a day of rest, but of thanksgiving and enjoyment. When they collected round the preacher, sitting silent and motionless, with their heads uncovered, and thrown back in devout attention, the scene acquired a graver and deeper interest. I have never witnessed that spectacle on a calm, sunny day, without a sensation of thrilling pleasure; and often as I have seen it, the impression that it made continued ever fresh and beautiful. There was a mingled cheerfulness and solemnity in this sight, that attached itself to the spot, and I have afterwards felt in the midst of my studies or sports on school-days, a soothing calmness creeping over me, a feeling that the place was hallowed, like that which we experience when strolling in a grave-yard, or lingering in the aisle of a church.

My memory clings to this spot, as the scene of the most vivid pains and pleasures of my childhood. I pass over the detail of all the sufferings that I endured from the brutality of ignorant and tyrannical teachers; perhaps I was more sensitive than other children; but be that as it may, it is certain, that although I was fond of learning, and docile in my disposition, I imbibed, very early in life, a cordial hatred for the whole race of schoolmasters. But I loved my books, and my companions; I loved to play at ball, and run races; and I loved the schoolhouse grove, with its tall oaks and verdant lawn. I used to

-----

p. 45

linger on a neighboring hill, to look on that graceful swell, and those fine trees, and to wonder why I thought the landscape so attractive. Those who recollect their sensations on first entering a theatre, or reading a novel, can form some idea of my feelings. That first play, and first novel, remain through life impressed upon the imagination, as standards with which all similar objects are compared; and it was thus, that the most interesting spot that attracted my young fancy, became to me the beau ideal of rural and romantic beauty.

There was another charm connected with this spot, the secret of which I will now disclose to the reader, although for many years I hardly dared acknowledge it to myself. My cousin Lucy was my school companion, and I never think of that green hill, without seeing her slender form, gliding among its shades, with the same calm blue eye, and meek countenance, and soft smile, that she wore when we were children. I hardly know why I loved Lucy better than any body else, for she was several years my senior, and never was my playfellow. I romped and laughed with the other girls, and played them all sorts of tricks; but I never hid her bonnet, or pinned her sleeve to that of her next neighbor. From her childhood she was sedate and womanly; her deportment was always delicate and dignified; there was a something about her that repelled familiarity, while the winning softness of her manners invited love and respect. When I came near to Lucy, I was no longer a wild, mischievous boy, but was elevated into a better and more rational being, by the desire that I felt to please and serve her.

-----

p. 46

We had a succession of schoolmasters, the most of whom were illiterate men, who remained with us but a few months. At last there came one of higher pretensions than the rest. He strolled into the neighborhood on foot, and so great was his modesty, that it was some time before any body discovered his acquirements, or suspected the object of his visit. At length he proposed, with some diffidence, to fill the vacant situation of teacher, and, having produced his credentials, was readily admitted to that thankless office. He was altogether a different man from any of his predecessors. His temper was even, his heart kind, his manners easy, and he had the rare talent of commanding respect, and communicating knowledge, without the appearance of an effort. He was as bashful as a girl, and as artless a being as ever lived. Every body liked him; his good sense, his cheerfulness, his inoffensive manners, and industrious habits, made him the favorite of young and old.

It was customary in those days, for the schoolmaster to board with his patrons, each one entertaining him for a week at a time, in rotation; an arrangement which, while it divided the burthen of his subsistence equally, enabled the whole neighborhood to become personally acquainted with the pedagogue. When the latter happened to be a dull, prosing dog, scantily supplied with good manners and good fellowship, the week of his reception wore heavily away, the table was less plentifully spread than usual, and the whiskey jug was sure to have suffered some disaster on the day previous

-----

p. 47

to his arrival. The head of the family indulged himself on such occasions, in liberal remarks upon the idleness and effeminacy of learning, and the good wife by frequent allusions to the scarcity of provisions, and the high price of schooling, gave the unfortunate teacher to understand that he was considered as a mere incubus upon the body politic, a Mr Nobody, who was only tolerated, and fed, and allowed to sit in the chimney corner, for the purpose of keeping the children out of mischief. But if the schoolmaster was a pleasant fellow, one who read the newspapers, and played the fiddle, and told a good story, the week of his visitation brought holiday times, and high doings, to the farmer’s hospitable fireside. Then the good man heard the news, the girls heard the violin, and the mistress of the house found a patient auditor to the recital of all the misadventures which had befallen the family, within the scope of her memory. Then the boys wore their holiday clothes every day, the hospitable board groaned under a load of good things, and the cheerful family enjoyed seven long days of good humor and good eating.

Of all schoolmasters, Mr Alexis, the gentleman above alluded to, was the most popular one that ever darkened the door of a farm house. In his time, the ‘schoolmaster’s week,’ was a week of festival. He not only read the news, and played the fiddle, but could sing a good song, and recite the veracious biography of a hundred real ghosts. He could explain all the hard words in the Testament, all the outlandish names in the newspapers, and all the strange hieroglyphics which are mischievously set down in the almanac, to puzzle the brains of simple

-----

p. 48

country folks. Then he was affable, and talkative; with all this he was good humored, and, what perhaps was more effective than all the rest, he was good looking. With such qualifications, he was always a welcome visiter, and I can well remember the stir that his coming occasioned in my father’s house. On the preceding Saturday, there was a universal scrubbing; the floors, the windows, the chairs, the pewter plates, the milk pails, and the children, were all scrubbed. The dimity curtains that lay snugly packed away in the great press, sprinkled with lavender and rose leaves, were now brought forth, and hung over the parlor windows; and the snow white counterpanes, that were kept for great occasions, were ostentatiously spread upon the beds. The yard was swept, and the great weeds that had been suffered to grow unmolested, were plucked up; and the whole messuage, out houses, tenements, and appurtenances, made to look as fine and as smart, as the nature of the case would admit. Then such baking, and brewing, and cooking! The great oven teemed with huge loaves, and rich pastry; yielding forth from its vast mouth, puddings, and pies, and tarts enough to have foundered a whole board of aldermen. The fatted calf was killed, the brightest ornaments of the pig-sty and poultry yard were devoted to the knife, and the best blood of the farm was freely spilled to furnish forth delicate viands, with which to pamper the appetite of that important and popular character, the schoolmaster.

I am often singular in my opinions; for I do not consider myself bound to believe anything, merely because every body else believes it. As to the schoolmaster, I

-----

p. 49

disliked him from the very first; and when everybody else praised him, I was silent. I had an inherent antipathy against al pedagogues. I viewed them as our natural enemies, a race created to scourge and terrify children; and for the person in question, I entertained a special and particular aversion. This was the more singular, as I was by nature confiding and placable, and never indulged a malignant feeling towards any other human being. He treated me with kindness, instructed me with unwearied patience, and I verily believe would have found the road to my heart, had I not suspected, that he was searching out the way that led to my cousin Lucy’s. I was always jealous of her, because the disparity of our ages placed her at a distance which almost extinguished hope, and because she always treated me as a boy and a relation, and either never did, or never would see, that I cherished feelings towards her, infinitely more tender than any that the mere ties of consanguinity could have awakened. A boy in love becomes cunning beyond his years. Unable to enter the lists as a candidate, and obliged to look on in silence, he becomes the secret and vigilant enemy of his unconscious rival. I was continually watching the schoolmaster and my cousin Lucy; and not a glance, nor a blush, nor a touch of the hand escaped my jealous eye. An indifferent observer would have seen nothing in their intercourse to excite the slightest suspicion; an enamored boy, who had loved devotedly from the first dawn of intelligence, read volumes of meaning in every act and look. The conduct of both of them was perfectly delicate and unexceptionable. There was not the least approach to gallantry on

-----

p. 50

his part; not an inviting, or an encouraging glance, on hers; but I could mark the softened tone of his voice, and the involuntary reverence of his manner, when he addressed her. I could detect the brightening of his eye when she spoke, and the courteous bow with which he replied to any question from her, so different from the common-place civility with which he treated his other female pupils. He often walked home with her, but never without other company, for she was always surrounded by children, one or two of whom she held by the hand, as if to prevent the possibility of a tète-a-tète. Perhaps she never had a thought that there was any particular meaning in his attentions; but there is an instinct in female delicacy, and although it might never have occurred to Lucy, that her teacher had opportunities beyond other men, which required that she should place a careful watch over her affections, nature regulated her conduct. I was often with them; they conversed without constraint, and never spoke of love, or courtship, or marriage. But he pointed out to her the finest traits of the landscape, gathered for her the choicest flowers, and discoursed of poetry; sometimes reciting the most beautiful passages, in so eloquent a tone, that I could have knocked him down, and was ready to quarrel with Lucy, for the apparent interest with which she listened. Often did I wish that he was a thousand miles off, or that I was a schoolmaster.

It would be too tedious to set down all the mischievous pranks that I played our teacher, in revenge for his supposed attachment to my cousin. Though fond of learning, I obstinately persisted in a resolution to owe

-----

p. 51

nothing to his teaching; and more than once disgraced him and myself, by wilful blunders, at our public examinations. I incited the biggest boys into conspiracies against his peace and dignity. Once when he was going to a tea-party at my uncle’s, a little better dressed than usual, a troop of us scampered past him as he was crossing a miry brook, and pretending not to observe him, splashed a shower of mud and water over his only holiday suit. We sent him one day into a large company with a grotesque figure chalked on his back; and on another occasion, scorched off his eyebrows by exploding gunpowder under his nose, while he was intently engaged in working a problem in Algebra. None of these persecutions ever ruffled his temper; and when my mother, who could not believe that the fault was mine, reproached him with the slowness of my progress, he mildly told her that the greatest geniuses were often dull boys at school, and that I would no doubt make a shining man.

At length the term of the schoolmaster’s engagement expired, and my heart bounded with joy, when I heard that he was going to quit the country. I was at my uncle’s on the morning of his departure, when he called to take leave of the family. Lucy was in the garden, and Alexis went there to look for her. Young as I was, I could readily comprehend that a latent passion would be most apt to betray itself in a parting interview, and that of all places in the world, a garden is the fittest to excite tender thoughts in the bosom of young lovers. In a moment, a thousand thoughts flashed through my mind—in another moment, love and jealousy prompted

-----

p. 52

me to observe a meeting which my foreboding heart told me would be fraught with more than usual interest. It was a mean act, but jealousy is always mean. I was to young, too much in love, and too angry, to reflect; and if I had reflected, who could have thought it improper to witness anything which could possibly take place between two such perfect beings, as my cousin Lucy and the schoolmaster?

I crept secretly to the garden, and from the covert of a thick hedge, saw Alexis approach my cousin. He took her hand, and told her that he had come to bid her farewell; that he had bade adieu to all his other friends, and had deferred calling upon her until the last, because to part with her was more painful than all the rest. There was a touching softness in his voice, and a corresponding melancholy clouded his features. ‘What a canting rascal,’ said I to myself; ‘I ’m afraid Lucy will never be able to stand it.’

He then dropped her hand, and began to pluck twigs from a peach tree, while Lucy was industriously engaged in demolishing a great rose. At last he said, ‘There is one subject—’ Lucy stooped down and began to pull the weeds from a tulip bed. The schoolmaster stopped, and looked embarrassed.

‘Silly fellow!’ said I exultingly, ‘why does he not kneel down, and lay his hand upon his heart?’ I took courage when I saw his trepidation, believing that he would never be able to tell his love, or that Lucy would discard so clumsy a lover.

‘Miss Lucy—’ said the schoolmaster.

‘Sir!’ said Miss Lucy.

-----

p. 53

‘What a canting villain!’ said I.

Mr Alexis looked round, as if fearful of observation.

‘He looks as if he were stealing,’ said I; ‘and well he may, the vile pedagogue!’

Alexis sighed, threw down his eyes, and resumed, ‘There is one subject, Miss Lucy, upon which I have long wished—’ He looked up, but Lucy was several paces off, twining the delicate vines of a honey-suckle through the lattices of the summer-house.