The Token, edited by Samuel Griswold Goodrich (Boston: Gray & Bowen, 1832)

-----

[p. 1 blank]

-----

[p. 2 blank]

-----

[p. 3 blank]

-----

[p. 4]

Note. The figures, inserted in the outlines of the letters forming the word ‘Token,’ on the opposite page, are taken from ancient medals. They are explained as emblems of Genius, Imagination, Painting, Poetry and Knowledge.

-----

[p. 5; presentation page]

A. HARTWELL SC.

[The presentation page has been filled in as follows:

FROM

[Dr S. Rosa]

as a

TOKEN

of

[parental regard]

To

[Catharine O. Rosa] ]

-----

[p. 6 blank]

-----

[frontispiece]

Painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Engraved by J. Cheney.

GUARDIAN ANGELS.

Published by Gray Bowen, Boston.

R. Neale Print. Boston.

-----

[“fancy title page”; engraved title page]

Engraved by E. Gallaudet.

THE TOKEN

BOSTON, 1833.

-----

[p. 7; printed title page]

AND

ATLANTIC SOUVENIR.

A

CHRISTMAS AND NEW YEAR’S PRESENT.

EDITED BY S. G. GOODRICH.

BOSTON.

PUBLISHED BY GRAY AND BOWEN.

MDCCCXXXIII.

-----

[p. 8; copyright page]

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year eighteen hundred and thirty-two, by Samuel G. Goodrich, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of Massachusetts.

BOSTON:

Printed by Samuel N. Dickinson,

52 Washington Street.

-----

[p. ix]

PREFACE.

In issuing our sixth volume, it gives us pleasure to state that an arrangement has been effected with the publishers of the Atlantic Souvenir, by which that work has been united with the Token. Having thus been able to unite the efforts of the artists and writers who have before contributed to each of these publications, we may be allowed to hope that the present volume is, in some respects, superior to any of its predecessors.

The publishers have made great exertions to procure suitable embellishments. Their expenses in this department have been much larger than in any previous year. It is a subject of regret to them that they have been unable to obtain a larger number of original designs for their engravings. The extreme difficulty of procuring such as are appropriate must be their apology. The original subjects in the present volume are thought to possess great merit, and will add to the fame of the artists, to whom they have been indebted for them. As to the other engravings, they believe that the great beauty of many of them will compensate for the fact that they are from designs of European origin.

We have again to thank our literary friends for their numerous favors, and to request a continuance of their kind assistance. Our contributors are particularly requested to preserve copies of their articles, as from the multiplicity of communications received we can in no case promise to return them. They will also please bear in mind that no decision as to the insertion of a piece, can in general be announced to the author till near the time of publication.

It only remains to mention the necessary absence of the editor, while a portion of the volume was going through the press. A part of his duties has consequently been discharged by a friend.

Boston, October 1, 1832.

-----

[p. x]

EMBELLISHMENTS.

1. Presentation, drawn by E. Gallaudet, and engraved by A. Hartwell [Alonzo Hartwell].

2. Fancy Title Page, centre piece painted by A. Fisher, drawn and engraved by E. Gallaudet [Edward Gallaudet].

3. Vignette, altered, drawn and engraved, after a sketch of C. M. Metz, by A. Bowen [Abel Bowen] … 13

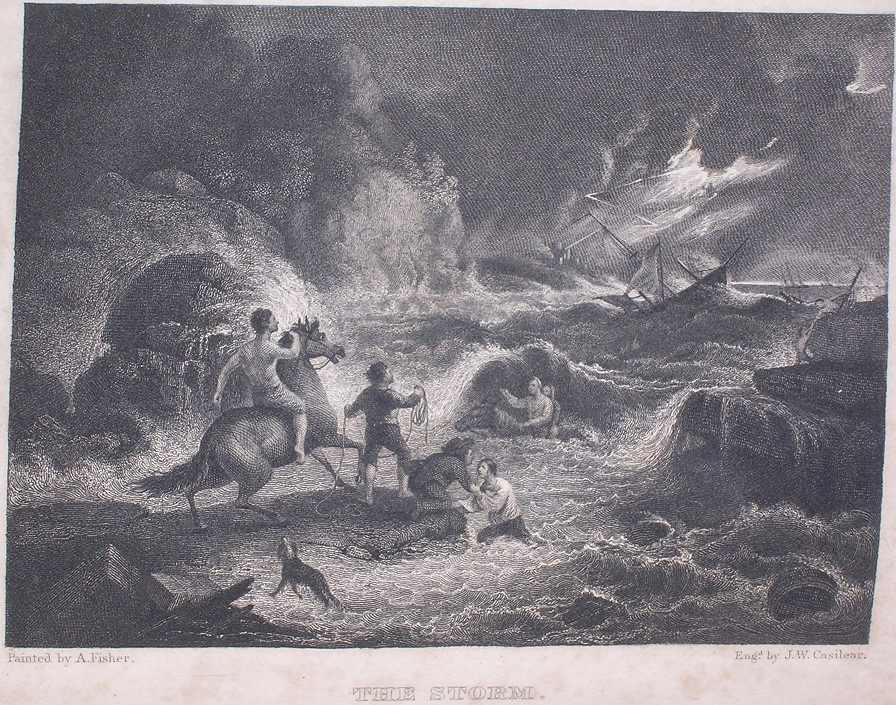

4. The Storm, painted by A. Fisher, engraved by G. W. Hatch [George W. Hatch] … 15

5. The Rescue, painted by A. Fisher, engraved by E. Gallaudet [Edward Gallaudet] … 33

6. Dancing, painted by S. Le Clerc, engraved by J. J. Pease [Joseph Ives Pease?] … 47

7. Guardian Angels, painted by Sir J. Reynolds, engraved by Jno. Cheney [John Cheney] … 73

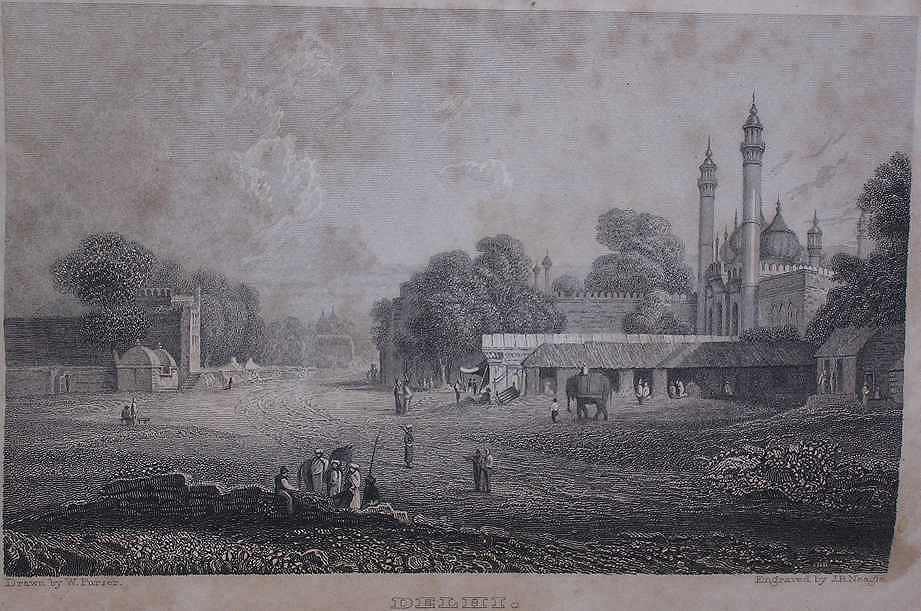

8. Delhi, Drawn by W. Purser, engraved by J. B. Neagle [John Neagle] … 113

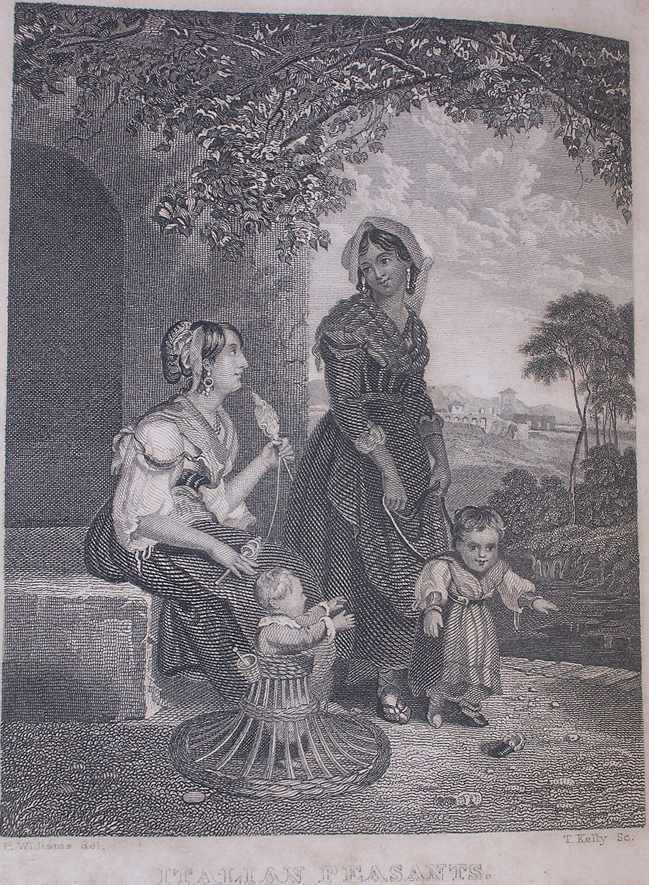

9. Italian Peasants, painted by P. Williams, engraved by T. Kelly [Thomas Kelly] … 135

10. Poor Relations, painted by Stephanoff, engraved by O. Pelton [Oliver Pelton] … 145

11. The Bridesmaid, engraved by G. B. Ellis [George B. Ellis] … 167

12. Joan of Arc, engraved by J. B. Neagle [John Neagle] … 185

13. The Shipwreck, painted by J. Vernet, engraved by J. B. Neagle [John Neagle] … 201

14. Belshazzar’s Feast, painted by J. Martin, engraved by W. Keenan [William Keenan] … 217

15. Audrey and Touchstone, engraved by A. Lawson [Alexander Lawson] … 249

16. Rural Amusement, painted by Sir T. Lawrence, engraved by G. B. Ellis [George B. Ellis] … 273

17. Mazeppa, painted by H. Vernet, engraved by Illman and Pilbrow [Thomas Illman and Edward Pilbrow] … 313

18. The Portrait, painted by Leslie, engraved by J. Cheney [John Cheney] … 337

19. A Scene in Spain, engraved by G. W. Hatch [George W. Hatch] … 353

20. Vignette, drawn by P. Violet, engraved by A. Bowen [Abel Bowen] … 354

-----

[p. xi]

CONTENTS.

Page.

To … … 13

The Storm [Epes Sargent] … 15

The Rescue … 33

Autumnal Musings—By John Pierpont … 34

Passage of the Beresina—By Mrs. Sigourney [Lydia Sigourney] … 43

Dancing Days … 47

Song—By Edward Vere … 48

The Seven Vagabonds—By the Author of ‘The Gentle Boy’ [Nathaniel Hawthorne] … 49

Lines on seeing a Soldier of the Revolution surrounded by his Family [Samuel Griswold Goodrich] … 72

Guardian Angels [B. B. Thatcher] … 73

The Bald Eagle [Henry Wadsworth Longfellow] … 74

The Artist [Samuel Griswold Goodrich] … 90

A Cure for Dyspepsia … 93

Delhi, a Tale of the East—By the Author of ‘The Affianced One’ [Elizabeth M. Sewell] … 113

Sir William Pepperell—By the Author of ‘Sights from a Steeple’ [Nathaniel Hawthorne] … 124

Italian Peasant’s Song—By Thomas Gray, Jun. … 135

Relief of Orleans … 136

To A Wild Deer—By Charles West Thomson … 140

Gibraltar—By the late J. O. Rockwell … 142

The Hypochondriac’s Good Night … 144

Visit of Poor Relations [Frances E. I. Calderon de la Barca] … 145

An Evening in Autumn [Henry Wadsworth Longfellow] … 150

The Canterbury Pilgrims [Nathaniel Hawthorne] … 153

The Bridesmaid—By H. F. Gould [Hannah F. Gould] … 167

Fall of Missolonghi—By B. B. Thatcher … 1[69]

Parisian Milliners and the Fishes—By Mrs. Sigourney [Lydia Sigourney] … 180

Life … 184

Joan of Arc [Frances E. I. Calderon de la Barca] … 185

The Shipwreck—By B. B. Thatcher … 201

-----

p. xii

Sketches of Conversation … 203

Belshazzar’s Feast—By Thomas Gray, Jun. … 217

[The Indian’s Welcome to the Pilgrim Fathers—By Lydia Sigourney … 220]

The Bridal Ring—By Miss Sedgwick [Catharine Maria Sedgwick] … 223

Dirge of a Young Poetess [Henry Pickering] … 247

Touchstone and Audrey [William Shakespeare] … 249

Blind Grandfather—By T. Flint [Timothy Flint] … 250

The Quaker—By H. F. Gould [Hannah F. Gould] … 265

A Night Thought—By Grenville Mellen … 270

Rural Amusement … 273

The Stormy Night [Hannah F. Gould] … 275

On a Noisy Politician—By C. Sherry [John O. Sargent] … 276

To a Lady—By Lawrence Manners [John O. Sargent] … 277

Song—By George Grey [John O. Sargent] … 280

The Stolen Match—By Caleb Cushing … 281

The Fountain of Love … 307

What is it? … 308

The Wasp and the Hornet—By Oliver Wendell Holmes … 309

The Philosopher to his Love [Oliver Wendell Holmes] … 310

My Native Land—By H. Vane [John O. Sargent] … 312

Mazeppa … 313

The Capture … 314

To a Fragment of Silk—By Mrs. Sigourney [Lydia Sigourney] … 335

A Portrait [Oliver Wendell Holmes] … 337

Trout Fishing … 338

The Fur Cloak … 342

Philip of Mount Hope [John O. Sargent] … 351

A Spanish Scene … 353

-----

[p. 13]

THE TOKEN.

To ........

I.

Nay, gentle lady, do not sigh

That summer’s sheen has passed away,

And things, almost too bright to die,

Have meekly yielded to decay.

II.

The forest leaves are sere and dead,

The wind has strewn the ground with flowers,

But yet not all the bloom has fled

From this wide varying world of ours.

-----

p. 14

III.

There is a flower, whose leaves unfold

Upon the chill autumnal air;

Unmindful of the wind or cold

It blossoms still serene and fair.

IV.

It issues from a nobler stem

Than gives the rose or lily birth,

And droops not quickly, when like them,

’Tis gathered from its native earth.

V.

It fears not Time’s relentless hand;

It shrinks not from the wintry weather;

Content to twine the golden band,

Which links remembering hearts together.

VI.

Then, lady, take the blooming flower;

Perhaps ’twill image to your eyes

The radiance of your summer bower,

The waving trees and sunny skies.

VII.

But should it haply fail to move

One pleasant thought, one bygone dream,

The gift, you know, at least may prove

A TOKEN—merely of esteem.

E.

-----

Painted by A. Fisher. Engd. by J. W. Casilear.

THE STORM.

Published by Gray Bowen, Boston.

-----

[p. 15]

THE STORM.

Our ship had traversed many a league

Of the unfathomed sea,

And on her homeward way had swept

With steady flight and free;

But now a hush was brooding

O’er the waters and the land,

And sluggishly she lay becalmed,

Close off our native strand.

She swung upon the smooth paved sea,

With canvas all unfurled;

While not a fluttering breath of air,

Her twining pennant curled.

Her snow-white sails flapped wearily

Against the creaking mast,

And stretched their folds in vain to catch

The whispering of the blast.

Three days and nights a hopeless calm,

Thus spread about our way,

And silent as a slumbering child,

The glassy billows lay.

Another morn—the wind rose up

From its foreboding sleep,

And hurled in wrath the giant waves,

Along the foaming deep.

-----

p. 16

The black and massy clouds bent down,

And darkened all the air,

Save where the severed edges caught

The lightning’s blazing glare:

In vain we strove with eager haste,

To reef the swelling sail;

Our mainmast trembled like a reed,

Before the sudden gale.

The ship drove on as if the storm

Itself had grasped the helm;

The surging waves bent o’er the deck,

They strove to overwhelm;

And on like chaff before the wind,

Our gallant vessel bore—

Until our straining eyes beheld

The dark cliffs of the shore.

She struck—and we—we perished not

Upon the desert sand;

For there were manly hearts to aid,

Beside that wave-beat strand.

But ere the cloud pavilioned sun

Had sunk beneath the wave,

Our bark, with all her bravery on,

Had found an ocean grave.

E. S.

-----

[p. 17]

THE SHIPWRECKED COASTER.

Who can stand before his cold?

Psalm cxlvii. 17.

There are few classes of men more exposed to hardships and disaster, than those employed in the coasting trade of New England, particularly in the winter season. So great are their risks of property and life, at that time of the year, that it is the custom of many to dismantle their vessels and relinquish their employment till the spring; although they can poorly afford this period of cessation from labor, and consequent loss of income. Among those engaged in conveying fuel from the forests of Plymouth and Sandwich to the Boston market, there are some who continue their business through the winter. But they incur great hazards, and sometimes meet with most disastrous issues. One of these events it is my present purpose to relate. The particulars I have ascertained from eye witnesses of a part of the scene; and from one who was a personal partaker of the whole.

In the winter of 1826-7 the weather was uncommonly severe for some weeks, during which the land was covered with snow, and the shores were encased in ice. It was a boisterous, cold and gloomy season. From my dwelling house there was a plain view of the little harbor of Sandwich, in which the few vessels employed in the business before named, shelter themselves, and

-----

p. 18

receive their lading of wood to be conveyed to Boston. Some of these were already dismantled for the winter; others were laden, and had been waiting a relaxation of the weather, in order to effect a passage. In that region a period of severe cold is commonly succeeded by rain. The north west wind which brings ‘the cold out of the north,’ gives place to a wind from a southerly point, which comes loaded with a copious vapor, and pours it down like a deluge. It so took place on the occasion to which I refer. Rain from the south east, had continued for two or three days, accompanied with tempestuous wind and occasional thunders and lightenings. [sic] It had dissolved much of the snow; but had filled the roads and low and level places with water. The ground being hard frozen retained the water on its surface, and this, with the remaining snow half dissolved, rendered the aspect of nature cheerless, and the moving from place to place uncomfortable. About noon, on the sixteenth of January, the rain ceased, and the weather being comparatively warmer than it had been, gave some prospect of a few days in which business might be done.

In the afternoon of that day, perceiving that there were some dry places on which the foot might be safely set, I embraced the opportunity to walk forth; glad to inhale the fresh air and meet the faces of men, after having been so long confined by the weather. The wind was comparatively soft, but gusty; the air was loaded with vapors, and, in the higher regions, clouds of all shapes and varying densities, were seen rolling over each other in different directions, as if obeying no

-----

p. 19

guidance of the wind, but pursuing each an inward impulse of its own.

While doubting, for a moment, which way to walk, I beheld, on an eminence, not far distant, a solitary individual, with his face towards the harbor, seeming to be deeply intent on something there taking place. An impulse of curiosity moved me to approach him, when I discovered him to be an old experienced master in the coasting trade.

I accosted him in the customary style of salutation, but he answered me not a word. His eye was intently following the motions of a small schooner, loaded with wood, which was slowly moving toward the mouth of the harbor. My own eye pursued the motion of his, till the Almira, (the schooner’s name,) had rounded the point, forming the west side of the harbor, and hoisting her sails stood towards the north. As soon as he saw this, he lifted his hands and exclaimed, ‘He has gone out of this harbor, and he will never come into it again!’ I remarked that the wind was southerly, and of course fair. But he paid no attention to the remark. He again lifted his hands, repeated his exclamation, and, with a sorrowful countenance, departed.

I stood awhile observing the progress of the schooner. It was not very rapid. The wind was vacillating, and shifting round about her, as if uncertain in what direction to establish itself. And the vessel seemed as if conscious of the uncertainty of the wind, and therefore, undecided as to the position of her sails and rudder.

The master of the Almira was Josiah Ellis, a man of between fifty and sixty years of age. He was one whose

-----

p. 20

gigantic frame seemed able to abide the fiercest ‘pelting of the pitiless storm.’ He had so often encountered the violence of the elements, and had so often conquered them by the simple energy of a vigorous constitution, that he took little care to guard himself against them. Reckless of what was to come, if he were sufficiently clad and armed for the present state of winds and seas, he thought not of what might be their condition, or his necessities for meeting them to-morrow. When, therefore, he felt a southerly wind and a favoring tide, he launched out for his voyage, with no crew but himself, his son Josiah, and John Smith, a seaman; little regardful that winter was still at its depth, and that an hour might produce the most perilous changes.

Thus prepared and manned, the Almira held on her way with a slow progress for several hours. The wind was changeful, but continued to blow from the southerly quarter, till they had passed Monimet point, a jutting headland about twelve miles from Sandwich harbor, which makes out from the south easterly side of Plymouth, some miles into the sea. It is a high rocky promontory, dangerous to approach; which interferes so much with the passage of vessels from Sandwich to Boston, that, while compelled to avoid it, they yet go as near to it as safety will admit. Beyond this, on its north westerly side, is a bay, at the bottom of which is Plymouth harbor; a safe place when you are once within it; but so guarded with narrow isthmuses on the north and south as to render the entrance difficult, and in tempestuous weather dangerous. They passed Monimet point about ten o’clock, and having Plymouth

-----

p. 21

light for a landmark, were working slowly across the outer part of the bay; but under the discouragements of a dark night, a murky atmosphere, ‘a sky foul with clouds,’ and a wind so varying, that no dependence could be placed on it for a moment. For some hours, they seemed to make no progress; and were rather waiting in hope for some change, than fearing one. The master himself was at the helm, Smith was walking to and fro upon the deck, occasionally adjusting a rope, or altering the position of a sail, and the younger Ellis had lain down on a bench in the cabin. Suddenly the master’s voice was heard, calling all hands in haste. His little crew hurried towards him, and looking towards the north west they saw a clear, bright, and cold sky, about half up from the horizon; the clouds were hastening away towards the south east, as if to avoid some fearful enemy, and new stars were appearing at each successive moment in the northern and western region of the heavens.

Beautiful as this sight was, in the present circumstances it was only appalling. It indicated a rapid change to severe cold, the consequences of which must be terrible. All was immediately bustle and agitation with the scanty crew. The first impulse was to run into Plymouth for shelter. But unfortunately that harbor lay directly in the eye of the wind, and there was little encouragement that they could make their way into it. They tacked once or twice, in hopes to attain the entrance, but having little sea room, and the wind becoming every moment more violent, and the cold more severe, they were constantly foiled; till in one of the sudden motions of

-----

p. 22

the vessel, coming with disadvantage to the wind, the main boom was wrenched from the mast. The halyards were immediately let go, and the mainsail came down, crashing and crackling as it fell, for it had already been converted to a sheet of ice. Too furl it, or even to gather it up, was impossible. It lay a cumbrous ruin on the deck and partly in the sea; a burden and a hinderance on all their subsequent operations.

Their next resource was to lay the vessel to the wind. This they effected by bracing their frozen foresail fore and aft, and loosing the gib. It was not in their power to haul it down. Its motion in the wind soon cracked its covering of ice, and in so doing, rent the substance of the sail itself. It was subsequently torn in pieces. The vessel now obeyed her helm, came up to the wind, and so remained.

While engaged in these operations, the anxious seamen had little opportunity to observe the heavens. But when they now looked up, behold the whole sky was swept clear of clouds as if by magic. The stars shone with unusual brilliancy. The moon had risen before the change of the wind, but had been invisible on account of the density of the clouds. She now appeared in nearly full-orbed lustre. But moon and stars seemed to unite in shedding that stern brightness which silvers an ice rock, and appears to increase its coldness. The brightness of the heavens was like the light of the countenance of a hard philosopher’s ungracious Deity—clear, serene, and chilling cold. They turned towards the wind, and it breathed upon their faces cuttingly severe, charged not only with the coldness of the region

-----

p. 23

whence it came, but also with the frozen moisture of the atmosphere, already converted into needles of ice.

From the care of their vessel, they began to look to that of their persons. They had been wet with the moisture of the air, in the earlier part of the night, and drenched with the spray which the waves had dashed over them during their various labors. This was now congealed upon them. Their hair and garments were hung with icicles, or stiffened with frost, and they felt the nearer approach of that stern power which chills and freezes the heart. But in looking for proper defences against this adversary of life, it was ascertained that the master had taken with him no garments, but such as were suited for the softer weather in which he had sailed. The outer garments of the son had been laid on the deck, and in the confusion of the night, had gone overboard. Smith, likewise, had forgotten precaution, and was wholly unprovided against a time like this. So that here were three men, in a small schooner, with most of their sails useless encumbrances, spars and rigging covered with ice, themselves half frozen, exposed to the severest rigors of a winter’s sky and winter’s sea, and void of all clothing, save such as was suited for moderate weather or the land.

In this emergency, they sought the cabin, and with much difficulty succeeded in lighting a fire; over which they hovered till vital warmth was in some measure restored. On returning to the deck, they found their perils fearfully increasing. The dampness and the spray which had stiffened and loaded their hair and garments, had in like manner congealed in great quantities about the

-----

p. 24

rigging, and on the deck, and over the sails. The spray as it dashed over the vessel, froze wherever it struck; several inches of ice had gathered on deck, small ropes had assumed the appearance of cables, and the folds of the shattered mainsail were nearly filled. The danger was imminent, that the accumulating weight of the ice would sink the schooner; yet all means of relieving her from the increasing load were utterly out of their power.

It being now impossible either to proceed on the voyage, or to gain shelter in Plymouth, there was no alternative but to endeavor to get back to their own harbor. It was difficult to make the heavy and encumbered vessel yield to her helm. As to starting a rope, the accumulated ice rendered it impossible. Nevertheless by persevering effort, they got her about; and as wind and tide set together that way, they cleared Monimet point, and came round into Barnstable Bay once more. They were now but a few miles from their own homes. Even in the moonlight, as they floated along, they could discern the land adjacent to the master’s dwelling house; and they earnestly longed for the day, in hopes that some of their friends might discover their condition, and send them relief. It was a long, perilous and wearisome night. The cold continued increasing every hour. The men were so chilled by it, and so overcome with exertion, that after they had rounded the last named point, they could make but little effort for preserving their ship. They beheld the ice accumulate upon the deck, the rigging and sails; they felt the vessel becoming more and more unmanageable, and their own danger growing more imminent every moment; yet were wholly unable to

-----

p. 25

avert the peril, or hinder the increase of its cause. It was with them,

‘As if the dead should feel

The icy worm around them steal,

And shudder as the reptiles creep,

To revel o’er their rotting sleep;

Without the power to scare away

The cold consumers of their clay.’

Morning at last began to dawn. But in its first grey twilight they could only perceive that they had been swept by the land they desired, the home they loved. Yet not so far, but that in the dim distance, they could see smoke from their chimney top, reminding them of the dear objects of their affections, from whom they were thus fearfully separated, and between whose condition and their own so dreadful a contrast existed. They looked between themselves and the shore, saw the impossibility of receiving assistance from their friends; and abandoning their vessel to fate, sought only to save themselves from perishing of cold.

Their last remaining sail had now yielded to the violence of the blast, and its accumulated burden of ice. It hung in shattered and heavy remnants from the mast. The vessel left to its own guidance, turned nearly broadside to the wind, and floated rapidly along, as if seeking the spot on which it might be wrecked. They passed the three harbors of Sandwich, that of Barnstable and Yarmouth, either of which would have afforded them safe shelter, could they have entered it. But to direct their course was impossible. With hearts more and more chilled as they drifted by these places of refuge,

-----

p. 26

which they could see, but could not reach, they floated onward to their fate.

From a portion of the town of Dennis, there makes out northerly into the sea, a reef of rocks. On the westerly side of this, there is a sandy beach, on which a vessel of tolerable strength might be cast without being destroyed; on the easterly side there is a cove, having a similar shore, which is a safe harbor from a north west wind. But the reef itself is dangerous.

In the early part of the day, January seventeenth, an inhabitant of Dennis beheld from an eminence this ill fated schooner, floating down the bay, broadside towards the wind; her sails dismantled, covered with ice, gleaming like a spectre in the cold beams of a winter’s morning. He raised an alarm and hastened to the shore, where he was shortly joined by such of the inhabitants as the sudden emergency allowed to collect. Many were seamen themselves; they knew the dangers and the hearts of seamen, and were desirous to render such assistance as they might.

The strange vessel was seen rapidly approaching the reef of rocks, before named. She was so near, that those on land could look on board, but they saw no man. They could perceive nothing but the frozen mass of the disordered sails; the ropes encrusted with ice, to thrice their proper size, and objects so mingled in confusion, and so heaped over with ice, that even experienced eyes could not distinguish whether these were frozen human beings, or the common fixtures on a vessel’s deck. Thinking, however, that there might be living men on board, who if they could be roused, might change the

-----

p. 27

direction of the schooner, so as to avoid the approaching death shock, they raised a shout, clear, shrill, and alarming. Whether it was heard they knew not. But very soon, the three men emerged from the cabin, and exhibited themselves on deck; shivering, half clad, meeting at every step a dashing spray, frozen ere it fell, and exposed to a cutting wind, as if they were

‘—all naked feeling, and raw life.’

‘Put up your helm,’ exclaimed an aged master, ‘make sail, and round the rocks; there’s a safe harbor on the leeward side.’ Lest his words might not be heard, he addressed himself to their eyes; and by repeated motions, wavings, signs and signals, well known to seamen, warned them of the instant danger, and pointed the direction in which they might avoid it. No movement on board was seen in consequence of this direction and these signals. Ellis and his two men felt that such effort would be unavailing, and did not even attempt it.

It was a moment of thrilling interest to both spectators and sufferers. The difference of a few rods, on either side, would have carried the vessel to safety and preserved the lives of the men. The strait forward course led to instant destruction. Yet that strait forward course the schooner, with seeming obstinacy, pursued, as if drawn by mysterious fascination; and hurried toward the rocks by a kind of invincible desire. Near and more near she came, with her incumbered bulk, till she was lifted as a dead mass on a powerful wave, and thrown at full length upon the fatal ledge.

The men on board, when they felt the rising of their vessel for her last fatal plunge, clung instinctively to

-----

p. 28

such fixtures as they could grasp, and in solemn silence waited the event. In silence they endured the shock of her striking; felt themselves covered not now with spray, but with the partially frozen substance of the waves themselves, which made a high way across the deck, filled the cabin, and left them no place of retreat, but the small portion of the quarter abaft the binnacle, and a little space forward near the windlass. To the former place they now retreated, as soon as they recovered from the shock, and there they stood, drenched, shivering and ready to perish; expecting at every moment the fabric under their feet to dissolve; and feeling their powers of life becoming less and less adequate to sustain the increasing intensity of cold.

‘We will make an effort to save them;’ said the agonising spectators of the scene. A boat was procured, and manned by a hardy crew, resolved to risque [sic] their lives for the salvation of their imperilled, although unknown fellow men. The surf ran heavy, and was composed of that kind of ice-thickened substance, called technically sludge; a substance much like floating snow. Through this she was shoved with great effort, by men who waded deep into the semi-fluid mass for the purpose. But scarcely had she reached the outer edge of the surf, when a refluent sea conquered and filled her. Fortunately, she had not gone so far, but that a long and slender warp cast from the shore, reached one of the men. He caught it and attached it to the boat, which was drawn back to land by their friends, and no lives were lost.

They on the wreck had gazed with soul absorbing interest, on this attempt at their rescue. They witnessed

-----

p. 29

its failure, and their hearts died within them. One of them was soon after seen to go forward and sit down on the windlass. ‘Rise, rise and stir yourself,’ exclaimed many voiced at once. They had not read the maxim of Dr. Solander, concerning people exposed to severe cold; ‘He that sits down will sleep, and he that sleeps will wake no more.’ They knew this truth by the sterner teachings of the experience of associates of their own, and by the sayings of the fathers, whose wisdom they revered. Hence their exclamation to him who had taken his seat. It was Smith. He rose not, however, at their call, and they said mournfully, one to another, ‘he will never rise again.’ He did not. In truth, in a little while he was so encrusted with ice, that they could not distinguish the human form from other equally disguised objects that lay around it; and when afterwards they got on board the body was gone. It had been washed away, no one knew when, nor has it ever been known that the sea has given up this dead.

The father and son now stood alone. The only shelter they could obtain from the icy wind and drenching sea, was by occasionally screening themselves on the lee side of the low binnacle. But there they experienced so soon the commencement of the deadly torpor, that they ceased making use of this refuge, and only sought to keep themselves in motion. But resolution, struggling against a disposition of nature, fails at last. The father was seen to go forward and seat himself as Smith had done before. Again the warning cry was raised, and again it was disregarded. ‘We will save him yet,’ it was exclaimed by the sympathising spectators. The

-----

p. 30

boat was again manned, and again launched, and reached beyond the surf in safety. But to get on board the wreck was utterly impossible. They came so near that they could speak to the younger Ellis, and hear his voice in reply. But such was the violence of winds and waves dashing on the rocks and over the wreck, that they could approach no nearer. They were compelled to turn about, leaving the father to sleep the sleep of death, with scarce a hope that the son could be saved. But they encouraged him to persevere in his efforts to keep from falling asleep. They told him that the rising tide would probably lift the vessel from her present position and bring her where they could come on board: that they would keep a constant watch and embrace the first practicable means for his deliverance. He heard them, saw them depart, and with a sad heart took his station on the cabin stairs, where standing knee deep in the half frozen water that filled the cabin, he could in some measure screen his thin clad form from the cold wind. But here he twice detected himself in falling asleep, and left the dangerous post; preferring to expose himself to the bleak wind on the quarter rather than sit down beneath a shelter and die. There he made it his object to keep himself in motion, and the people, when they saw him in danger of relinquishing this only means of preservation, shouted, and moved, and stirred him to new effort.

It took place as the seamen had predicted. The rising tide lifted the vessel from her dangerous position, and brought her on to a sand, where the people with much effort got on board, about four o’clock in the afternoon.

-----

p. 31

They found young Ellis on the quarter deck holding on to the tiller ropes. He had become too much exhausted to continue his life-preserving movements, and the stillness of an apparently last sleep had been for some time stealing over him. His hands were frozen to the ropes which they grasped, his feet and ancles were encrusted with ice, and he was so far gone that he was scarce conscious of the presence of his deliverers.

Their moving him roused him a little. Yet he said nothing, till as they bore him by his father’s body he muttered, ‘there lies my poor father,’ and relapsed into a stupor, from which he only awaked after he had been conveyed on shore, and customary means were employed for his restoration. Through the humane attention of the inhabitants, he was restored, but with the ultimate loss of the extremities of his hands, and his feet. He still survives, a useful citizen, notwithstanding these mutilations. But the memory of that fearful night and day is fresh in his mind. It taught him, in truth, the inefficiency of human strength, when matched against the elements of nature; and made manifest, likewise, the value of that kindness of man to man, which leads him to watch and labor, and expose even his life for the shipwrecked stranger; to minister to his wants, and nurse his weakness, and safely restore him to his family and friends. A child of their own could not have been more kindly or carefully attended than he was, nor more liberally provided for, by the humane people among whom he was cast. I doubt not there is a recompense for them, with him who hath said,

-----

p. 32

[‘]inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.’

Reader, I know not what interest you may take in my simple narrative, but I have given you a true account of the SHIPWRECKED COASTER.

Sandwich, June, 1832.

-----

Painted by A. Fisher. Engraved by E. Gallaudet.

THE RESCUE.

Published by Gray Bowen, Boston.

R. Neale, Print.

-----

[p. 33]

THE RESCUE.

The father has clasped his child,

And sprung with her on his steed,

And away through the depths of the forest wild,

From their savage foes they speed.

They have reached the opposing stream—

They have dashed through its silent tide,

And swift as the lightning’s vivid gleam,

They pass up the green hill’s side.

But look! upon their rear,

Gliding with rapid pace,

The Indian hunters fast appear,

And press upon the chace. [sic]

A pistol-shot in the air!

And the foremost bite the ground;

And the courser springs like a startled hare,

Away at the sudden sound.

Away, down the rocky height,

And on through the tangled wood,

He moves in his free and rushing might,

Unseen and unpursued.

And soon to her mother’s love,

The father his fair child gave,

And their mingled thanks went up above

To Him who is strong to save.

-----

[p. 34]

AUTUMNAL MUSINGS:

SUNDAY EVENING.

BY JOHN PIERPONT.

We have withdrawn ourselves from the busy crowd, from the noise and the cares of the world, from social converse, and even from the domestic circle, to think upon our ways and to cultivate an acquaintance with our Maker among the things which he hath made. We are amidst the works of nature. We are in the school of natural religion. The volume is open before us on whose pages of light God has written his own character with his own hand. We do not, indeed, see therein his whole character, for not all of his works are visible by any of his creatures, in any part of the universe; still less are all his designs disclosed by the works of his hand. We neither see all that he has done, nor all that he will do; neither all that he has done to load his other creatures with blessing, nor all that he has done and will do, to crown us with immortality. But though we see but a part of his ways, though a cloud still rests upon all but the lower steps of his throne, all that he has shown us in the volume of nature, is presented to us in the light of unerring truth. If, in his word, he has spoken upon topics on which his works are silent, the silence of the latter does not contradict the testimony of the former. So far as the light of nature does lead us in our inquiries

-----

p. 35

after the Author of nature, its guidance may be followed with entire confidence. If the light of revelation leads us still farther on, happy shall we be if we walk in that light, and grateful should we be that it is given: but no book can be a revelation from God which speaks of him in a manner that contradicts the language in which he has spoke of himself in the great volume of nature.

We would now seek to approach him by walking, for a few moments, in the light which in his works he hath shed upon our path. We cannot, indeed, look forth upon all his works. We cannot contemplate the great machine of nature in all its parts, and take particular notice of all its complicated operations, in all worlds, and at all times. We cannot even dwell upon all the effects of revolving seasons upon this little world of ours. We are minute objects when we come to compare ourselves with the other works of God, immeasurably extended, incalculably multiplied, perpetually varied as they are. Our view must consequently be narrow. We are, at best, beings of a day; and a great part of even that day must be actively engaged, and consequently we can devote but a little time to the business of retired meditation. But we can spend a few moments in reading one page of the great volume that is open before us, and in gathering instruction from it in relation to its Author and to ourselves.

The day is holy that is now coming to its close. It is congenial to holy meditations. It is a day of rest. The labors that fatigue the body are suspended. The cares that rack the mind, are, or should be, shut out from it. A calm is breathed over the passions that convulse the

-----

p. 36

soul. We have been engaged in the worship of God. What day then is more proper than this, on which to meditate upon the object of our worship.

The season is favorable. It is the fall of the year:—a season which, while it goes by us with the wealth, seems also to move along with the gravity of age. There is a composed sobriety, a seriousness, a tender melancholy in the fall, which softens the heart of him who looks upon the fading beauties of the year; and which lifts it insensibly to the Being who is seen to have crowned it with his goodness. The very fields seem to ask repose, as if weary of the delights, or exhausted with the labors of the summer; and, in the air that goes over them, there is so much sedateness, there is something so cool and temperate, that it seems impossible, while we breathe it, that our hearts should be frozen with ingratitude, or that they should burn with unhallowed desires.

It is now eventide. With little effort we may call up to our minds the scene that has so often arrested our attention as we have walked alone in the fields of our fathers; when the toils of the day were over, when the sun was going down in glory, yet a glory so mild that the eye could repose upon it; when the shadows of evening were stretched out, and its dews were falling around us. What one of us, is there, that cannot easily recall to his mind, in all its composing, tranquilizing power—with all its interesting circumstances softened by time, and consecrated by grateful recollections—the picture of an autumnal evening, when he has been out in his native fields, meditating at the eventide! Can

-----

p. 37

there be any whose days, from infancy to the present hour, have been so exclusively spent amidst the hum of business, in the glowing focus of a crowded population, that his memory can furnish him with no scene wherein Nature dwells so nearly alone as to make it interesting to him as the dwelling of Nature? The walks of no one, surely, can have been so narrow that he has never seen the sickly hues of autumnal woods, and meadows white with frost; and never witnessed the silent, yet touching sadness of the world, when its light was departing from it.

It is in the cool, calm breath of evening, that the Deity seems peculiarly present. Our first parents are said to have heard the voice of the Lord God, walking in the garden in the cool of the day. The voice of the present Spirit was heard as the leaves of their arbor rustled in the evening breeze: and, conscious of their guilt, they shrunk away into deeper shade, as if to retire from the meditations of that religious hour. It was in the same holy season, that Jeremiah felt the phrophetic [sic] spirit come over him. ‘The hand of the Lord,’ says he, ‘was upon me in the evening.’ And Jesus, ‘when he had sent the multitudes away, went up into a mountain, apart, to pray; and when the evening was come, he was there alone.’ There he might meditate upon the events of the day that was gone; there he might look forward with humble resignation, to scenes of future trial: there he might commune with his heavenly Father, and, like his father David, might say, while ‘I remember the days that are past, while I meditate on all they works, and muse on the work of thy hands—I will stretch forth my hands unto thee.’

-----

p. 38

Indeed it seems impossible that he, who withdraws himself from the world in the sober light of the retiring day, who walks alone in fields, or among trees that are brightened with the sun’s last rays; and who then will meditate upon the works of God, and muse upon all that is calm and fair around him; should not then stretch forth his hands, and open his heart to the Author of so much loveliness and peace.

‘When day, with farewell beam, delays

Among the opening clouds of even,

And we can almost think we gaze

Through golden vistas into heaven;

Those hues that make the sun’s decline

So soft, so radiant, Lord, are thine.’

He who can stand forth beneath the autumnal sky, amidst glories so mild, and can be deaf to the whisper of the breeze that speaks of God, and blind to the golden ray that points to his throne; who can then limit his desires to a world that shall so soon grow dark; who can quit such a scene at such a moment, without one thought of God, without one wish, one prayer for heaven, must be blind to all that is lovely in virtue, and deaf to the eloquence of Him who speaks from the skies.

How eloquent, how impressive is this preaching of nature! How valuable the lessons it inculcates upon the mind of him who meditates at eventide, upon what he sees! He looks at the lofty elm which the frost has touched. Its leafy honors have faded, and are falling away; but the grass beneath it is still green. Why then should he envy the proud, or despise him who is of low estate? For the pitiless blast of adversity shall sweep over the one, and bear away all but a faded

-----

p. 39

remnant of his glories, and the proud one shall sigh when he feels that even that remnant, must soon be resigned, and that too in the evening of his life; while the other, though humble, is bright and cheerful to the last, and patiently waits till the white robe of death is spread over him.

From the same objects too, he who meditates in the field upon the works of God, and who says, with David, ‘My meditations of him shall be sweet,’ may learn the goodness, as well as the wisdom, and the mild majesty of the Author of nature. The elm has thrown its shade around during the sultry season, and has tempered the blaze of many a summer noon. It continued to do so, so long as that shade is grateful to the traveller that rested, or the laborer that toiled, or the cattle that ruminated beneath it. But the frosts and cold winds of autumn have succeeded, and man now asks the genial warmth of the sun, and shuns the chilling shade; and lo! the shade that he shuns is taken away, and the light which he asks is let in upon him. The beasts of the field, however, still claim their verdant food, and the green pasture is spared to them.

In the dimness that at eventide gradually steals upon the objects before us, and renders our view of them indistinct, and our judgment of them uncertain, we see the doubts that darken our prospects of futurity, and the uncertainty that is thrown over every thing before us in life. It is this evening magic, that in changing the appearance of distant objects, presenting some in a disproportionate magnitude, and giving others a gaudy coloring that does not belong to them, invites us to reflect

-----

p. 40

upon the mutability of every thing earthly, and upon the flatteries and falsehoods of the visions of hope. The dwelling that crowns a distant hill, as its windows catch the sun’s last ray, seems illuminated with living rubies; and while we gaze upon it, the mansion which youthful fancy rears for our future abode, and which hope sees in the distance, seems not less brilliantly lighted up with the smiles of love and prosperity, and peace; not less radiant with the honors that shall shine upon it in the sunset of our life. But the sun sinks behind the hills, and with it the glittering pageant is gone. The house that, a moment before, was so brilliant, has become perhaps the comfortless hut of poverty, or at best, the homely dwelling of patient, unaspiring labor. At such a moment, then, it is our own fault if we do not infer that the splendor which a warm imagination has thrown around our future condition, will almost as certainly fade into the sober scene of careful toil; if not even into the sad one of penury and pain. And then, while the feeling of the uncertainties of the future is thus pressed upon our heart, when we feel that our most strenuous efforts may fail, and that our wisest plans may be defeated; that it may be ours to walk unfriended through the vale of obscurity, to be chilled as the cloud of neglect settles upon us, or as the blast of adversity sweeps over us; it is then that we naturally endeavor to fortify ourselves against the evils which we may be called to encounter, and to prepare our hearts to give up, without a murmur, the good things which we may be called to resign, and the brilliant prospects that have once flattered us; and it is then that we almost irresistibly lift our eyes

-----

p. 41

to the Great Fountain of good; and in the subdued tone of filial submission, say ‘Father, thy will be done.’

It is in such a contemplative moment, too, when the great ruler of the day is retiring in majesty from the world, when he is seen

‘Arraying with reflected purple and gold

The clouds that on his western throne attend,’

that our thoughts turn to the last moments of one whose life has been a blessing to mankind. It is then that we see the glorious exit of a good man from the world. We see with what sublime composure he can sink into the grave, who, in life, has been ‘a burning and a shining light;’ and it is then that our hearts must join in the prayer of the prophet of old, ‘Let me die the death of the righteous, and let my last end be like his!’

And lastly, it is when we go out to meditate in the field at eventide, when we linger there, in the temple of nature, till its swelling dome is lighted up with stars, till all around us is still, save perhaps the solemn murmur of the ocean, or the roar of the distant water-fall, or the moan of the autumnal blast, that seems to breathe a sigh of regret over the loveliness which it is commissioned to destroy; it is then, that meditation invites to worship; it is then that the heart rises, if indeed it can be moved, with feelings of reverence and profound devotion, towards the all pervading Spirit who sustains ourselves and all that we behold.

If there is any thing softening to the heart, it is the evening song of winds and waters; if any thing overwhelming, it is the grandeur of the skies. Can we listen to the one or gaze upon the other, without one

-----

p. 42

thought of him who thus speaks on earth, and shines in heaven? Must we not rather stand, like the father and mother of our race,

‘—and under open sky, adore

The God that made both sky, air, earth and heaven,

Which we behold; the moon’s resplendent globe,

And starry pole.’

If, like the father of Israel, we were often to retire from the world to meditate in the fields, at eventide, from how many of the pollutions of the world might we not escape! How many past errors might we not detect! and for the future what strength might we not give to our virtuous resolutions! How correctly might we come to estimate the relative importance of the present and the future! With what complacency might we dwell upon the character of God, and with what pleasure contemplate his continual presence! How might the mind be tranquilized at evening, after the agitations of the day; and when we feel the frost of age settling on our heads, and the winter of death advancing upon us, with what serenity might we view the shadows gathering and deepening around us; and in another life, how bright would our morning be!

-----

[p. 43]

PASSAGE OF THE BERESINA.

BY MRS. SIGOURNEY.

‘On with the cohorts, on! A darkening cloud

Of Cossack lances hovers o’er the heights,

And hark! the Russian thunder on the rear

Thins our retreating ranks.’

The haggard French,

Like summoned spectres facing toward their foes,

And goading on their lean and dying steeds

That totter ’neath their huge artillery,

Give desperate battle. Wrapped in volumed smoke,

A dense and motley mass of hurrying forms

Press toward the Beresina. Soldiers mix

Undisciplined amid the feebler throng,

While from the rough ravines the rumbling cars

That bear the sick and wounded, with the spoils

Torn rashly from red Moscow’s sea of flame,

Line the steep banks. Chilled with the endless shade

Of black pine forests, where the unslumbering winds

Make bitter music; every heart is sick

For the warm breath of its far, native vales,

Vine clad and beautiful.

Pale, meagre hands

Outstretched in eager misery, implore

Quick passage o’er the flood. But there it rolls,

’Neath its ice curtain, horrible and hoarse,

A fatal barrier ’gainst its country’s foes.

-----

p. 44

The combat deepens. Lo! in one broad flash

The Russian sabre gleams, while the sharp hoof

Treads out despairing life. With maniac haste

They throng the bridge, those fugitives of France,

Reckless of all, save that one desperate chance,

Rush, struggle, strive,—the powerful thrust the weak,

And crush the dying.

Hark! a thundering crash,

A cry of horror! Down the broken bridge

Sinks, and the wretched multitude plunge deep

’Neath the devouring tide. That piercing shriek

With which they took their farewell of the sky,

Did haunt the living, as some doleful ghost

Troubleth the fever dream. Some for a while

With ice and death contending, sink and rise,

While some in wilder agony essay

To hold their footing on that tossing mass

Of miserable life, making a path

O’er palpitating bosoms. ’Tis in vain!

The keen pang passes, and the satiate flood

Shuts silent o’er its prey. The severed host

Stand gazing on each shore. The gulph, the dead,

Forbid their union. One sad throng is borne

To Russian dungeons, one with shivering haste

Spread o’er the wild, thro’ toil and pain to hew

Their many roads to death.

From desert plains,

From sacked and solitary villages,

Gaunt famine springs to seize them; winter’s wrath

Unresting day or night, with blast and storm,

And one eternal magazine of frost,

-----

p. 45

Smites the astonished victims. King of Heaven!

Warrest thou with France, that thus thine elements

Do fight against her sons? Yet on they press,

Stern, rigid, silent, every bosom steeled

By the strong might of its own misery

Against all sympathy of kindred ties;

The brother on his fainting brother treads,

Friend tears from friend the garment and the bread,

That last scant morsel which his famished lip

Hoards in its death pang. Round the midnight fires,

That fiercely through the startled forest blaze,

The dreaming shadows hover; madly pleased

To bask, and scorch, and perish, with their limbs

Crisped like the martyr’s, and their heads fast sealed

To the frost pillow of their fearful rest.

Turn back, turn back, thou fur clad emperor!

Thus toward the palace of the Tuileries

Flying in breathless speed. Yon wasted forms,

Yon breathing skeletons, with tattered robes,

And bare and bleeding feet, and matted locks;

Are these the high and haughty troops of France,

The buoyant conscripts, who from their blest homes,

Went freely at thy bidding? When the cry

Of weeping love demands her cherished ones,

The nursed upon her breast, the idol gods

Of her deep worship, wilt thou coldly point

The Beresina, the drear hospital,

The frequent snow mound on the unsheltered march,

Where the dead soldier sleeps?

Oh War! War! War!

Thou false baptized, who by thy vaunted name

-----

p. 46

Of glory, stealest o’er the ear of man,

To rive his bosom with thy thousand darts,

Disrobed of pomp and circumstance, stand forth,

And show thy written league with sin and death.

Yes, ere ambition’s heart is seared and sold,

And desolated, bid him mark thine end,

And count thy wages.

The proud victor’s plume,

The hero’s trophied fame, the warrior’s wreath,

Of blood dashed laurel, what will these avail

The spirit parting from terrestrial things?

One slender leaflet from the tree of peace,

Borne dovelike o’er the waste and warring earth,

Is better passport at the gate of Heaven.

-----

Painted by S. Le Clerc. Engraved by J. I. Pease.

DANCING.

Published by Gray Bowen, Boston.

-----

[p. 47]

DANCING DAYS.

What is Care? such a thing they say there is,

Though it never invades my laughing hours;

Can it come to a spot so green as this,

To sadden a maiden so crowned with flowers?

But my cheerful days will pass away,

As the aged say when my step they praise,

Sorrow will wrinkle my brow, they say,

If I should survive my dancing days.

But I live to dance and not to sigh,

Though others may weep if they will my dear,

I can only dance, yet I fain would fly

So light I seem when the pipe I hear.

What is youth, but a cheerful and mazy dance,

In which pleasure leads us a thousand ways;

What is life but a long and sweet romance,

In which all the days may be dancing days.

The waters dance through the banks of green,

Or bound along over rocky fall,

The clouds dance over the vault serene,

And I must dance, if I move at all.

Then the world let them call a place of wo,

Where a lover deceives and a friend betrays,

Or if love is a cheat and friendship a snare,

I will look for delight to my dancing days.

O.

-----

[p. 48]

SONG.

BY EDWARD VERE.

One thought for me, my love,

When the silent midnight hour

Touches all around, above,

With the magic of its power;

When the heart is full and deep

With the tenderest of feelings,

And the silken lid of sleep

Is raised to bright revealings.

If then thou chance to see

Gay visions flit before thee,

Many lovers bend the knee,

And promise to adore thee;

Let a thought of him arise,

Once a captive in thy net,—

But who now may thank the skies,

That he baffled a coquette!

-----

[p. 49]

THE SEVEN VAGABONDS.

BY THE AUTHOR OF THE GENTLE BOY.

Rambling on foot, in the spring of my life and the summer of the year, I came one afternoon to a point which gave me the choice of three directions. Straight before me, the main road extended its dusty length to Boston; on the left a branch went down towards the sea, and would have lengthened my journey a trifle, of twenty or thirty miles; while, by the right hand path, I might have gone over hills and lakes to Canada, visiting in my way, the celebrated town of Stamford. On a level spot of grass, at the food of the guide post, appeared an object, which though locomotive on a different principle, reminded me of Gulliver’s portable mansion among the Brobdignags. It was a huge covered wagon, or, more properly, a small house on wheels, with a door on one side and a window shaded by green blinds on the other. Two horses munching provender out of the baskets which muzzles them, were fastened near the vehicle: a delectable sound of music proceeded from the interior; and I immediately conjectured that this was some itinerant show, halting at the confluence of the roads to intercept such idle travellers as myself. A shower had long been climbing up the western sky, and now hung so blackly over my onward path that it was a point of wisdom to seek shelter here.

‘Hallo! Who stands guard here? Is the door keeper

-----

p. 50

asleep?’ cried I, approaching a ladder of two or three steps which was let down from the wagon.

The music ceased at my summons, and there appeared at the door, not the sort of figure that I had mentally assigned to the wandering show man, but a most respectable old personage, whom I was sorry to have addressed in so free a style. He wore a snuff coloured coat and small clothes, with white top boots, and exhibited the mild dignity of aspect and manner which may often be noticed in aged school masters, and sometimes in deacons, selectmen, or other potentates of that kind. A small piece of silver was my passport within his premises, where I found only one other person, hereafter to be described.

‘This is a dull day for business,’ said the old gentleman, as he ushered me in; ‘but I merely tarry here to refresh the cattle, being bound for the camp meeting at Stamford.’

Perhaps the moveable scene of this narrative is still peregrinating New England, and may enable the reader to test the accuracy of my description. The spectacle, for I will not use the unworthy term of puppet-show, consisted of a multitude of little people assembled on a miniature stage. Among them were artisans of every kind, in the attitudes of their toil, and a group of fair ladies and gay gentlemen standing ready for the dance; a company of foot soldiers formed a line across the stage, looking stern, grim, and terrible enough, to make it a pleasant consideration that they were but three inches high; and conspicuous above the whole was seen a Merry Andrew, in the pointed cap and motley coat of

-----

p. 51

his profession. All the inhabitants of this mimic world were motionless, like the figures in a picture, or like that people who one moment were alive in the midst of their business and delights, and the next were transformed to statues, preserving an eternal semblance of labour that was ended, and pleasure that could be felt no more. Anon, however, the old gentleman turned the handle of a barrel organ, the first note of which produced a most enlivening effect upon the figures, and awoke them all to their proper occupations and amusements. By the self-same impulse the tailor plied his needle, the blacksmith’s hammer descended upon the anvil, and the dancers whirled away on feathery tiptoes; the company of soldiers broke into platoons, retreated from the stage, and were succeeded by a troop of horse, who came prancing onward with such a sound of trumpets and trampling of hoofs, as might have startled Don Quixote himself; while an old toper, of inveterate ill-habits, uplifted his black bottle and took a hearty swig. Meantime the Merry Andrew began to caper and turn somersets, shaking his sides, nodding his head, and winking his eyes in as life-like a manner as if he were ridiculing the nonsense of all human affairs, and making fun of the whole multitude beneath him. At length the old magician, for I compared the show man to Prospero, entertaining his guests with a masque of shadows, paused that I might give utterance to my wonder.

‘What an admirable piece of work is this!’ exclaimed I, lifting up my hands in astonishment.

Indeed, I liked the spectacle, and was tickled with the

-----

p. 52

old man’s gravity as he presided at it, for I had none of that foolish wisdom which reproves every occupation that is not useful in this world of vanities. If there be a faculty which I possess more perfectly than most men, it is that of throwing myself mentally into situations foreign to my own, and detecting with a cheerful eye, the desirable circumstances of each. I could have envied the life of this gray headed show man, spent as it had been in a course of safe and pleasurable adventure, in driving his huge vehicle sometimes through the sands of Cape Cod, and sometimes over the rough forest roads of the north and east, and halting now on the green before a village meeting house, and now in a paved square of the metropolis. How often must his heart have been gladdened by the delight of children, as they viewed these animated figures! or his pride indulged, by haranguing learnedly to grown men on the mechanical powers which produced such wonderful effects! or his gallantry brought into play, for this is an attribute which such grave men do not lack, by the visits of pretty maidens! And then with how fresh a feeling must he return, at intervals, to his own peculiar home!

‘I would I were assured of as happy a life as his,’ thought I.

Though the show man’s wagon might have accommodated fifteen or twenty spectators, it now contained only himself and me, and a third person at whom I threw a glance on entering. He was a neat and trim young man of two or three and twenty; his drab hat and green frock coat with velvet collar, were smart, though no longer new; while a pair of green spectacles, that seemed

-----

p. 53

needless to his brisk little eyes, gave him something of a scholar-like and literary air. After allowing me a sufficient time to inspect the puppets, he advanced with a bow, and drew my attention to some books in a corner of the wagon. These he forthwith began to extol, with an amazing volubility of well-sounding words, and an ingenuity of praise that won him my heart, as being myself one of the most merciful of critics. Indeed his stock required some considerable powers of commendation in the salesman; there were several ancient friends of mine, the novels of those happy days when my affections wavered between the Scottish Chiefs and Thomas Thumb; besides a few of later date, whose merits had not been acknowledged by the public. I was glad to find that dear little venerable volume, the New England Primer, looking as antique as ever, though in its thousandth new edition; a bundle of superannuated gilt picture books made such a child of me, that, partly for the glittering covers, and partly for the fairy tales within, I bought the whole; and an assortment of ballads and popular theatrical songs drew largely on my purse. to balance these expenditures, I meddled neither with sermons, nor science, nor morality, though volumes of each were there; nor with a Life of Franklin in the coarsest of paper, but so showily bound that it was emblematical of the Doctor himself, in the court dress which he refused to wear at Paris; nor with Webster’s spelling book, nor some of Byron’s minor poems, nor half a dozen little testaments at twenty-five cents each. Thus far the collection might have been swept from some great book store, or picked up at an evening auction

-----

p. 54

room; but there was one small blue covered pamphlet, which the pedlar handed me with so peculiar an air, that I purchased it immediately at his own price; and then, for the first time, the thought struck me, that I had spoken face to face with the veritable author of a printed book. The literary man now evinced a great kindness for me, and I ventured to inquire which way he was travelling.

‘Oh,’ said he, ‘I keep company with this old gentleman here, and we are moving now towards the camp meeting at Stamford.’

He then explained to me, that for th present season he had rented a corner of the wagon as a book store, which as he wittily observed, was a true Circulating Library, since there were few parts of the country where it had not gone its rounds. I approved of the plan exceedingly, and began to sum up within my mind the many uncommon felicities in the life of a book pedlar, especially when his character resembled that of the individual before me. At a high rate was to be reckoned the daily and hourly enjoyment of such interviews as the present, in which he seized upon the admiration of a passing stranger, and made him aware that a man of literary taste, and even of literary achievement, was travelling the country in a show man’s wagon. A more valuable, yet not infrequent triumph, might be won in his conversations with some elderly clergyman, long vegetating in a rocky, woody, watery back settlement of New England, who, as he recruited his library from the pedlar’s stock of sermons, would exhort him to seek a college education and become the first scholar in his class. Sweeter and prouder yet

-----

p. 55

would be his sensations when talking poetry while he sold spelling books, he should charm the mind, and haply touch the heart of a fair country school mistress, herself an unhonoured poetess, a wearer of blue stockings which none but himself took pains to look at. But the scene of his completest glory would be when the wagon had halted for the night, and his stock of books was transferred to some crowded bar room; then would he recommend to the multifarious company, whether traveller from the city, or teamster from the hills, or neighouring squire, or the landlord himself, or his loutish hostler, works suited to each particular taste and capacity; proving, all the while by acute criticism and profound remark, that the lore in his books was even exceeded by that in his brain. Thus happily would he traverse the land; sometimes a herald before the march of Mind; sometimes walking arm in arm with awful Literature, and reaping everywhere, a harvest of real and sensible popularity, which the secluded book worms by whose toil he lived, could never hope for.

‘If ever I meddle with literature,’ thought I, fixing myself in adamantine resolution, ‘it shall be as a travelling book seller.’

Though it was still mid-afternoon, the air had now grown dark about us, and a few drops of rain came down upon the roof of our vehicle, pattering like the feet of birds that had flown thither to rest. A sound of pleasant voices made us listen, and there soon appeared halfway up the ladder, the pretty person of a young damsel, whose rosy face was so cheerful, that even amid the gloomy light it seemed as if the sunbeams were

-----

p. 56

peeping under her bonnet. We next saw the dark and handsome features of a young man, who with easier gallantry than might have been expected in the heart of Yankee-land, was assisting her into the wagon. It became immediately evident to us, when the two strangers stood within the door, that they were of a profession kindred to those of my companions; and I was delighted with the more than hospitable, the even paternal kindness, of the old show man’s manner, as he welcomed them; while the man of literature hastened to lead the merry eyed girl to a seat on the long bench.

‘You are housed but just in time, my young friends,’ said the master of the wagon. ‘The sky would have been down upon you within five minutes.’

The young man’s reply marked him as a foreigner, not by any variation from the idiom and accent of good English, but because he spoke with more caution and accuracy, than if perfectly familiar with the language.

‘We knew that a shower was hanging over us,’ said he, ‘and consulted whether it were best to enter the house on the top of yonder hill, but seeing your wagon in the road—’

‘We agreed to come hither,’ interrupted the girl, with a smile, ‘because we should be more at home in a wandering house like this.’

I, meanwhile, with many a wild and undetermined fantasy, was narrowly inspecting these two doves that had flown into our ark. The young man tall, agile, and athletic, wore a mass of black shining curls clustering round a dark and vivacious countenance, which, if it had not greater expression, was at least more active,

-----

p. 57

and attracted readier notice, than the quiet faces of our countrymen. At his first appearance, he had been laden with a neat mahogany box, of about two feet square, but very light in proportion to its size, which he had immediately unstrapped from his shoulders and deposited on the floor of the wagon. The girl had nearly as fair a complexion as our own beauties, and a brighter one than most of them; the lightness of her figure, which seemed calculated to traverse the whole world without weariness, suited well with the glowing cheerfulness of her face, and her gay attire combining the rainbow hues of crimson, green, and a deep orange, was as proper to her lightsome aspect as if she had been born in it. I hardly know how to hint, that, as the brevity of her gown displayed rather more than her ancles, I could not help wishing that I had stood at a little distance without, when she stept up the ladder into the wagon. This gay stranger was appropriately burdened with that mirth inspiring instrument, the fiddle, which her companion took from her hands, and shortly began the process of tuning. Neither of us, the previous company of the wagon, needed to inquire their trade; for this could be no mystery to frequenters of brigade musters, ordinations, cattle shows, commencements, and other festal meetings in our sober land; and there is a dear friend of mine, who will smile when this page recalls to his memory a chivalrous deed performed by us, in rescuing the show box of such a couple from a mob of great double fisted countrymen.

‘Come,’ said I to the damsel of gay attire, ‘shall we visit all the wonders of the world together?’

-----

p. 58

She understood the metaphor at once; though indeed it would not much have troubled me, if she had assented to the literal meaning of my words. The mahogany box was placed in a proper position, and I peeped in through its small round magnifying window, while the girl sat by my side, and gave short descriptive sketches, as one after another the pictures were unfolded to my view. We visited together, at least our imaginations did, full many of a famous city, in the streets of which I had long yearned to tread; once, I remember, we were in the harbour of Barcelona, gazing townwards; next, she bore me through the air to Sicily, and bade me look up at blazing Ætna; then we took wing to Venice, and sat in a gondola beneath the arch of the Rialto; and anon she set me down among the thronged spectators at the coronation of Napoleon. But there was one scene, its locality she could not tell, which charmed my attention longer than all those gorgeous palaces and churches because the fancy haunted me, that I myself, the preceeding summer had beheld just such an humble meeting house, in just such a pine surrounded nook, among our own green mountains. All these pictures were in crayons, and tolerably executed, though far inferior to the girl’s touches of description; nor was it easy to comprehend, how in so few sentences, and these, as I supposed, in a language foreign to her, she contrived to present an airy copy of each varied scene. When we had travelled through the vast extent of the mahogany box, I looked into my guide’s face.

‘Where are you going my pretty maid?’ inquired I, in the words of an old song.

-----

p. 59

‘Ah,’ said the gay damsel, ‘you might as well ask where the summer wind is going. We are wanderers here, and there, and every where. Wherever there is mirth, our merry hearts are drawn to it. To-day, indeed the people have told us of a great frolic and festival in these parts; so perhaps we may be needed at what you call the camp meeting at Stamford.’

Then in my happy youth, and while her pleasant voice yet sounded in my ears, I sighed; for none but myself, I thought, should have been her companion in a life which seemed to realize my own wild fancies, cherished all through visionary boyhood to that hour. To these two strangers, the world was in its golden age, not that indeed it was less dark and sad than ever, but because its weariness and sorrow had no community with their etherial nature. Wherever they might appear in their pilgrimage of bliss, youth would echo back their gladness, care stricken maturity would rest a moment from its toil, and age, tottering among the graves, would smile in withered joy for their sakes. The lonely cot, the narrow and gloomy street, the sombre shade, would catch a passing gleam like that now shining on ourselves, as these bright spirits wandered by. Blessed pair, whose happy home was throughout all the earth! I looked at my shoulders, and thought them broad enough to sustain those pictured towns and mountains; mine, too, was an elastic foot, as tireless as the wing of the bird of Paradise; mine was then an untroubled heart, that would have gone singing on its delightful way.

‘Oh, maiden!’ said I aloud, ‘why did you not come hither alone?’

-----

p. 60

While the merry girl and myself were busy with the show box, the unceasing rain had driven another way farer into the wagon. He seemed pretty nearly of the old show man’s age, but much smaller, leaner, and more withered than he, and less respectably clad in a patched suit of gray; withal, he had a thin, shrewd countenance, and a pair of diminutive gray eyes, which peeped rather too keenly out of their puckered sockets. This old fellow had been joking with the show man, in a manner which intimated previous acquaintance; but perceiving that the damsel and I had terminated our affairs, he drew forth a folded document and presented it to me. As I had anticipated, it proved to be a circular, written in a very fair and legible hand, and signed by several distinguished gentlemen whom I had never heard of, stating that the bearer had encountered every variety of misfortune, and recommending him to the notice of all charitable people. Previous disbursements had left me no more than a five dollar bill, out of which, however, I offered to make the beggar a donation, provided he would give me change for it. The object of my beneficence looked keenly in my face, and discerned that I had none of that abominable spirit, characteristic though it be of a full blooded Yankee, which takes pleasure in detecting every little harmless piece of knavery.

‘Why, perhaps,’ said the ragged old mendicant, ‘if the bank is in good standing, I can’t say but I may have enough about me to change your bill.’

‘It is a bill of the United States Bank,’ said I, ‘and better than the specie.’

-----

p. 61

As the beggar had nothing to object to the national credit, he now produced a small buff leather bag, tied up carefully with a shoe string. When this was opened, there appeared a very comfortable treasure of silver coins, of all sorts and sizes, and I even fancied that I saw, gleaming among them, the golden plumage of that rare bird in our currency, the American Eagle. In this precious heap was my bank note deposited, the rate of exchange being considerably against me. His wants being thus relieved, the destitute man pulled out of his pocket an old pack of greasy cards, which had probably contributed to fill the buff leather bag, in more ways than one.

‘Come,’ said he, ‘I spy a rare fortune in your face, and for twenty-five cents more, I’ll tell you what it is.’