The Token, edited by Samuel Goodrich, was one of many gift annuals available to early 19th-century readers. These lavishly bound, lushly illustrated collections of poetry and prose were intended as Christmas and New Year’s gifts—reminding us that in early 19th-century America, New Year’s was a gift-giving holiday. Gift books were published both for children and for adults, though the audiences often overlapped: some pieces by Goodrich appearing in The Token were reprinted in his works for children, including Robert Merry’s Museum. Goodrich saw in The Token a chance to promote American writers and engravers. He succeeded quite well, especially with the writers, who included John Neal, Catharine Sedgwick, N. P. Willis, Lydia Sigourney, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Eliza Leslie, and—in retrospect, most significant—Nathaniel Hawthorne. The first volume of The Token appeared in 1827; the last was published in 1842. Almost always, it was a decorative volume, with a handsome binding, fulsome end papers, and contents that were—well—decorative. Scenic views and scenic ladies were staples in the poetry; the prose tended to be lightly humorous, slightly sensational, and delicately edifying. Most of what appeared in The Token was innocuous.

The volume for 1835 is 376 pages bound in embossed leather. The pages are gilded on all exposed sides, and the text is embellished by 11 engravings, snapshots of which are reproduced here. In keeping with the book’s intended purpose as a gift, a presentation plate is included at the front, and the list of engravings appears before the table of contents for the text—establishing for shoppers that there was a good number of illustrations for the money.

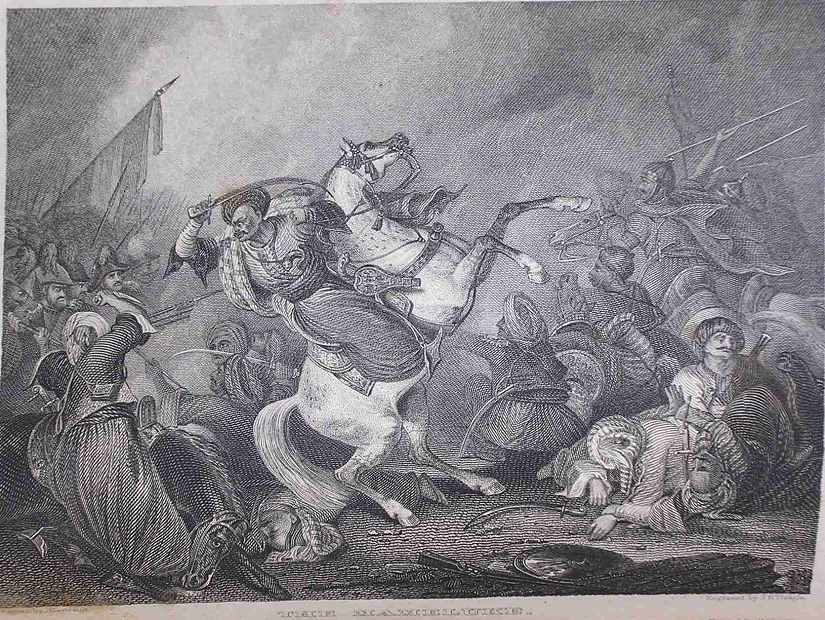

While Goodrich wanted the Token to represent American themes, this volume abounds in non-American settings and characters. Historical women include Mary Stuart—with whom the female readers of the Token were expected to sympathize—and Catherine the Great—with whom they weren’t. Benvenuto Cellini boasts of firing the shot that kills the Duke of Bourbon, in “Bourbon’s Last March;” “The Bride” involves a European count. “The Mameluke” and “The Cobbler of Brusa” pursue Middle-Eastern themes. Even Catharine Sedgwick mingles romance and religious persecution against the Paterins in 13th-century France, in “St. Catharine’s Eve.” The story may have been inspired by Valperga, by Mary Shelley, in which a character is excommunicated by the Catholic church, having become a Paterin, whose beliefs were antithetical to the Church’s traditions. Valperga was reviewed on the same page (p. 105) as the second edition of Sedgwick’s New England Tale in the British Monthly Review for May 1823; it’s tempting to think that Sedgwick read Shelley’s book and found an enticing theme. Sedgwick’s story is extremely anti-Catholic—a theme woven through several volumes of the Token. Here, not only do we have characters executed for their religious beliefs, but an evil archbishop persuading the king to oppress Jewish people.

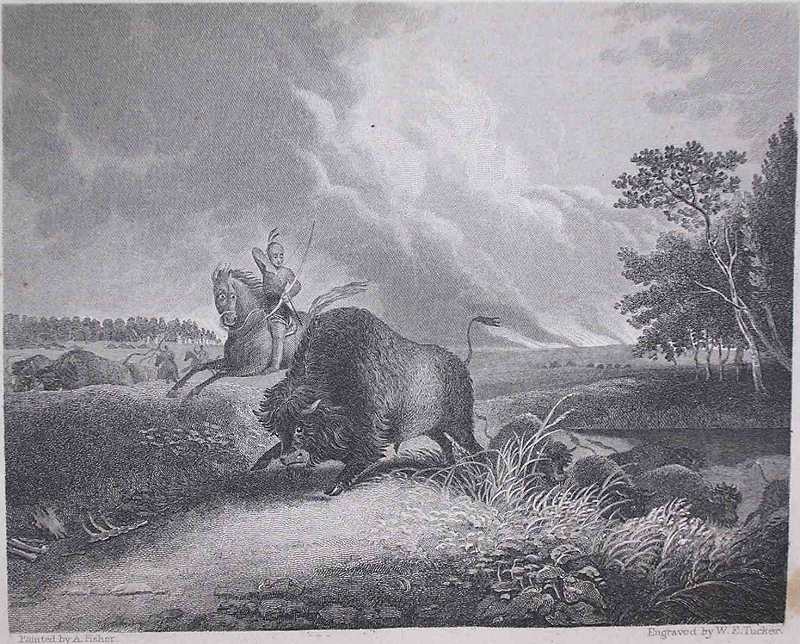

There are, of course, American themes. Nathaniel Hawthorne has three stories, all set in the U.S. “Alice Doane’s Appeal” involves the witch trials in Salem, Massachusetts; “The Mermaid” is about New England fisherfolk; “The Haunted Mind” snapshots a night in a small town. Eliza Leslie’s “The Reading Parties” is an amusing look at social politics in a tiny village. The American prairie is the subject of “A Legend of the Prairies,” by James Hall (The Harpe’s Head is an historical novel including as characters the Harpe brothers, who murdered and pillaged in 18th-century Kentucky and Ohio), and “The Buffalo Hunt.” Native Americans haunt these prairies, hunting the buffalo and menacing travelers. “Fort Mystick,” by Lydia Sigourney, details the destruction of Native Americans in Connecticut in a story built on stereotypical tropes, while “The Departed Tribes” laments that Native Americans are fading, falling, and dying.

Women in the stories are often vulnerable and young. Catherine the Great is the villain of “The Fate of a Princess,” demanding the “removal” of a naive teenager who could supplant her and smilingly adding the girl’s wedding ring to the jewels on her hand after the girl has been betrayed. Mary Stuart is “lovely and … innocent” and endured “unmerited sufferings;” readers evidently were expected to sympathize with the young and vulnerable woman eventually executed for plotting to usurp the throne, rather than with the powerful and celebrated woman who held that throne. And, oh, are the heroines young. The biography of Mary Stuart ends before her twenties. The 21-year-old count in “The Bride” marries a 13-year-old; Sedgwick’s young heroine is sixteen. “The Fate of the Princess” is based on an historical incident in which a 30-year-old woman claimed to be the true heir to the throne; here, however, the woman is a 15-year-old girl. Pages and pages of the Token are given to florid descriptions of lovely innocents.

Dreams and stories are a minor theme in this volume, with the mother in Sedgwick’s “St. Catharine’s Eve” inspired by a dream she considers heaven-sent and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s narrator in “The Haunted Mind” mingling dream images with the realities of the night. Hawthorne explores stories and storytelling in “Alice Doane’s Appeal,” as the narrator reads aloud from his story of betrayal, and in “The Mermaid,” with the narrator telling stories beside the hearth. Eliza Leslie’s “The Reading Parties” makes references to a number of popular stories and poems.

Love and romance are complicated in this volume of the Token. First love is not always eternal. The narrator of “Consolation” falls in love with one woman and then another, and since each young woman has married another man, he hopes to fall in love with a third. The narrator of “To E—” has loved Mary, but “E.” is exactly like her, so he falls in love with her. Sarah Josepha Hale shows how a marriage can survive bankruptcy in “The Broken Merchant,” but a surprising number of the marriages are simply politically or economically expedient. The count in “The Bride” marries his 13-year-old only because he must marry in order to inherit a fortune, and she is likely to be the most malleable female he could find. Alexis Orloff marries the unsuspicious princess in the way of Catherine the Great because he fears his plot has been exposed; Mary Stuart marries for political reasons, though her brief marriage is treated as romantic. Romances blossom in “The Reading Parties,” but the marriage appears to be inspired by the bride’s bank account. (Given the groom’s propensity for bankruptcy, it’s tempting also to see their union as some sort of punishment for the bride’s pride.)

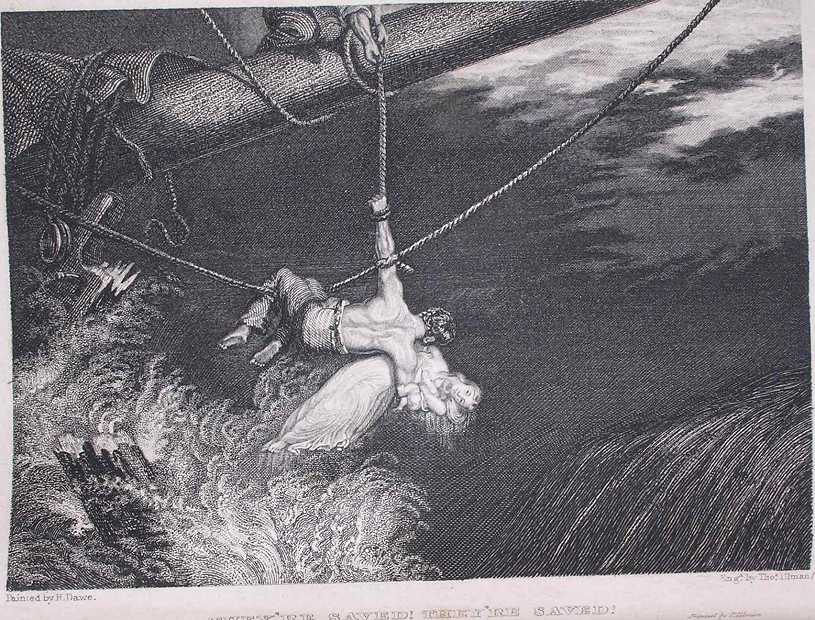

As usual, several pieces are written around the steel engravings that grace the book. “Bourbon’s Last March,” in fact, points that out. Having suggested to Robert Walter Weir that he should add historical figures to the Italian landscape he was painting, Gulian Crommelin Verplanck acceded to Weir’s demand that he write the story pictured in the image. Two dramatic engravings highlight the dramatic shift in Hannah F. Gould’s “Changes On the Deep,” the impending death of an innocent in “My Child! My Child!” and the heroic rescue in “They’re Saved! They’re Saved!” Gould gives a religious twist to the latter phrase.

Few volumes of the Token make as many references as this one. “The Reading Parties” is filled with references to writers and works. “The Widow and Her Son” appears in The Sketch-Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., by Washington Irving; “Alexander’s Feast” by George Frideric Handel. The wreck of the Ariel is described in The Pilot, by James Fenimore Cooper. “Paulding” is James Kirke Paulding, who would have a piece in the next volume of the Token. Mr. Snitterby and Mr. Sniffin act out a scene from Pizarro, by Richard Brinsley Sheridan, a 1799 play in which Alonzo and Rolla are Peruvians fighting the Spanish ledd by Pizarro; captured after a battle, Alonzo is held in a dungeon and awaiting execution, but Rolla helps him disguise himself and takes his place, helping Alonzo to escape. Mr. Ugford recites “The Pet-Lamb” (1800) by William Wordsworth, where a young girl feeds a lamb abandoned by its mother. “The Young Novice,” by Mary Russell Milford, features Bridget Plantagenet, daughter of Henry IV, who was taken to a nunnery at age 10. The poem was printed in Literary Souvenir, edited by Alaric A. Watts. (London, England: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown & Green, 1829). The Battle of Hohenlinden is in “Hohenlinden,” by Thomas Campbell; the quoted stanza is halfway through the poem. Mr. Edwards (and Mr. Binnage) are enamored of “The Song of Marion’s Men,” by William Cullen Bryant (1831): Francis Marion (“the Swamp Fox”) led a small band of soldiers against British forces in South Carolina during the American Revolution; in the poem, Marion’s men cheerily boast of sleeping “[o]n beds of oaken leaves” in “the good greenwood” and harassing the British.

Reviewers of the volume were somewhat critical of the engravings, not only their non-American subjects, but the quality of the artwork: “[W]ho ever saw a man making love with such an immense wrist?” the New England Magazine quipped. That editor was less interested in critiquing the text, which would involve having to do the work of reading it. “Can any one be so unreasonable as to require us to read it?” he asks. “The idea is not to be harbored.”

The entire volume is transcribed here, with spelling intact. Spelling could be erratic. In Sedgwick’s “St. Catherine’s Eve,” “Agnés” is sometimes “Agnes.” The traveler looking for “Westchester,” Pennsylvania, near the battle of the Brandywine, will be disappointed unless looking for “West Chester”—perhaps because either the author of the piece or the editor of the volume was more familiar with the spelling of the county in New York. And there are vagaries of early American spelling: “monysyllable,” “shew.” Unfortunately, scanning all the illustrations would damage the book, so the engravings are quick (and sometimes distorted) snapshots. Reviews are on a separate page.

-----

[presentation page]

Drawn by G. Harvey, A. N. A. Engraved by E. Gallaudet.

Presented to [blank space]

By [blank space]

-----

[“fancy title page”; engraved title page]

Painted by A. Colin. Engraved by E. Gallaudet.

Print. by R. Andrews.

THE TOKEN.BOSTON, 1835.

-----

AND

ATLANTIC SOUVENIR.

A

CHRISTMAS AND NEW YEAR’S PRESENT.

EDITED BY S. G. GOODRICH.

BOSTON.

PUBLISHED BY CHARLES BOWEN.

MDCCCXXXV.

-----

[p. 2; copyright page]

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year eighteen hundred and thirty-four, by Charles Bowen, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of Massachusetts.

![]() As the publisher of this work, is also the sole proprietor,

it is requested that all communications relating to business

matters may be addressed to him; those which relate to the

editorial department may be addressed as usual to S. G.

Goodrich, care of C. Bowen.

As the publisher of this work, is also the sole proprietor,

it is requested that all communications relating to business

matters may be addressed to him; those which relate to the

editorial department may be addressed as usual to S. G.

Goodrich, care of C. Bowen.

Samuel N. Dickinson, Printer,

52 Washington Street.

-----

[p. 3]

CONTENTS.

Page.

To F. … 5

St. Catharine’s Eve—By Miss Sedgwick [Catherine Maria Sedgwick] … 7

Bourbon’s Last March—by G. C. Verplanck [Gulian Crommelin Verplanck] … 37

Will you go? … 61

The Rival Bubbles: A Fable—by S. G. Goodrich … 62

Good Night … 64

The Youth of Mary Stuart—by L******* [Henry Wadsworth Longfellow] … 65

The Haunted Mind—by the author of Sights from a Steeple [Nathaniel Hawthorne] … 76

The Mountain Stream—By B. B. Thatcher … 83

Alice Doane’s Appeal—By the Author of the Gentle Boy [Nathaniel Hawthorne] … 84

Consolation—By Lawrence Manners [John O. Sargent] … 102

The Mameluke—By Grenville Mellen … 103

The Mermaid: A Reverie [Nathaniel Hawthorne] … 106

What shall I bring thee, Mother? … 122

The Bride … 124

Lady Lake—Pencilled while sailing [John O. Sargent] … 158

The Silver Cascade in the White Mountains [Samuel G. Goodrich] … 159

The Cobbler of Brusa: A Turkish Tale … 162

The Bird of the Bastile—By B. B. Thatcher … 174

Fort Mystick—By Mrs. Sigourney [Lydia Sigourney] … 177

The Wreck [Samuel G. Goodrich] … 212

The Dream of Youth [Samuel G. Goodrich] … 213

The Reading Parties: A Sketch—By Miss Leslie [Eliza Leslie] … 216

Job Fustick; or, the Dyers: A Story of all colors … 246

Sonnet to Lord Edward Fitzgerald—By A. D. Woodbridge … 253

Tears—By A. A. L. … 254

The fate of a Princess … 255

Children—What are they?—By J. Neal [John Neal] … 280

The Old Elm of Newbury—By H. F. Gould … 299

A Legend of the Prairies—By the Author of the Harpe’s Head [James Hall] … 303

The Cottage Girl—By V. V. Ellis [John O. Sargent] … 319

Sonnet [John O. Sargent] … 321

The Broken Merchant—By Mrs. S. J. Hale [Sarah Josepha Hale] … 322

Monody—By Mrs. Sigourney [Lydia Sigourney] … 343

The Field of Brandywine—By William L. Stone … 346

Duties of Winter—By F. W. P. Greenwood … 359

The Buffalo Hunt … 367

The Days that are past [Epes Sargent] … 368

To a Lady who called me capricious [John O. Sargent] … 369

To E. … 370

Changes on the deep—By Miss Gould [Hannah F. Gould] … 371

The Departed Tribes … 376

-----

[p. 4]

EMBELLISHMENTS.

1. Presentation Plate, drawn by Harvey, engraved by E. Gallaudet.

2. Title-Page, Painted by A. Colin, engraved by E. Gallaudet.

3. Bourbon’s Last March, painted by R. W. Weir, engraved by Jas. Smillie. … 3[7]

4. Will You Go? painted by A. Fisher, engraved by J. B. Neagle. … 61

5. The Mameluke, engraved by J. B. Neagle. … 103

6. The Mountain Stream, painted by J. Doughty, engraved by J. B. Neagle. … 83

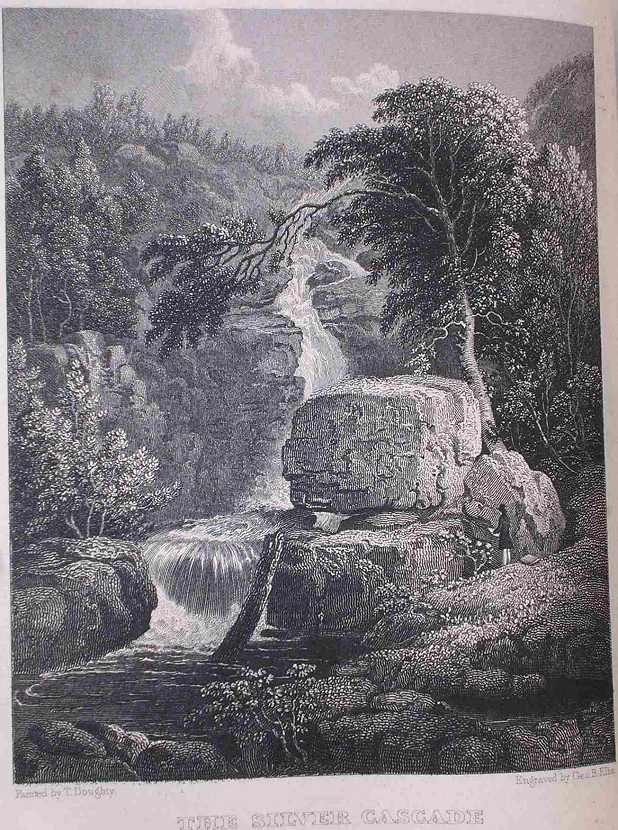

7. The Silver Cascade, painted by J. Doughty, engraved by G. B. Ellis. … 159

8. The Dream of Youth, painted by Guerin, engraved by Cheney. … 213

9. The Young Princess, engraved by Cheney. … 255

10. The Cottage Girl, painted by E. Landseer, engraved by Cheney. … 319

11. The Buffalo Hunt, painted by A. Fisher, engraved by W. E. Tucker. … 367

12. My Child! My Child! painted by H. Dawe, engraved by Thos. Illman. … 371

13. They’re Saved! They’re Saved! painted by H. Dawe, engraved by Thos. Illman. … 375

-----

[p. 5]

THE TOKEN.

—

TO F.

The spring, the summer, they are flown; away

On wizard wings they seek a genial sky,

While Autumn’s yellow leaves come whirling by,

Singing to fancy’s ear a plaintive lay,

Of youthful memories linked with winter’s gloom.

And if the heart will deeply listen, love,

Hope, fear, and every other thrilling string,

Swept like sweet Eol’s harp by Music’s wing,

Tremble, as if these leaves from heaven above,

Whispered at once of childhood and the tomb.

Such is the voice of nature, and its tone

Doth weave strange contrasts into harmony,

Then wilt thou not forgive that I for thee

Have gathered leaves as varied for thine own?

Wilt thou not lend thy favor, tho’ the book

May tell of lovers in the title-page,

Met as by chance within some Grecian cave,

To speak the whispers of a golden age,—

While yet another leaf, a legend grave

May tell, of battle with the Mameluke?

-----

p. 6

I prithee listen to the gusty strain

That sweeps thy window, blending with the wail

Of coming winter, summer’s parting gale.

Look at yon lovely landscape; ’tis a plain

O’er which the mountain’s frown is darkly thrown.

The eye is taught to love the blushing flower

Within the cypress’ shadow, and the ray

Of sunshine in a tomb doth seem to play

With darkness in its secret, stolen bower,

More gaily that its revel is so lone.

Still dost thou blame the changeful page, and deem,

It all capricious that a song hath place,

Beside a sermon, shuffled face to face?

Look at thyself, fair lady! Is the theme

Not worthy of perusal? Yet the elf,

Called nature, with its ever changing brow,

Its landscapes, leaves, and fluctuating wind,—

I deem it less capricious far than thou—

Less lovely too I own,—but change thy mind,

And take this book—a semblance of thyself.

-----

[p. 7]

ST. CATHARINE’S EVE.

BY MISS SEDGWICK.

‘All is best though oft we doubt,

What th’ unsearchable dispose

Of highest wisdom brings about,

And ever best found in the close.’

Milton

‘On trouve dans la chronique de Raoul, Abbé de Coggeshall, sous cette année (1201) une histoire touchante qui montre à quel point l’enseignement religieux pouvoit être perverti, et combien le Clergé étoit loin d être le gardien des mœurs publiques.’

Early in the 13th century Agnés de Meran, the misstress-wife of Philip Augustus, held her court at the Chateau des roses Sur-Seine, not many leagues from Paris. The arts and luxuries of the time were lavished on this residence of the favorite. On one side of the Chateau, and leading out of the garden attached to it, was a winding walk, embowered by grape vines which, not being native in the north of France, and the art by which the gardener now triumphs over soil and climate being then in its infancy, were cultivated with great pains and royal expense. The walk, after extending some hundred yards, opened on a sloping ground, bounded by the Seine, and tastefully planted with shrubs and vines formed into arbours and bowers of every imaginable shape. The whole plantation was called Larigne. Parallel to a part of it ran the highway, hidden by a wall, excepting where it traversed an arched stone bridge that spanned the Seine, and which was itself almost embowered by tall acacias, planted at either end of it.

Late in the afternoon of a September day, when the warm air was perfumed with autumnal fruits, and the sun glancing

-----

p. 8

athwart the teeming vines, shot its silver beams across the green sward, and seemed, by some alchemy of the flowers to become molten gold as it touched their leaves, tinted with deep autumnal dyes; two ladies, followed by a Moorish servant girl, issued from the walk.

The eldest was tall and thin. The soft round lines of youth had given place to the angles of forty; but though she had lost the beauty, she had retained the grace (happily that charm is perennial) of youth, and added to it the fitting quality of matronly dignity. Born in Provence, she was an exception to the general hue of its natives, her complexion having an extreme fairness, and a texture as delicate as that of infancy. She had that organ, to whichthe Phrenologist is pleased to assign the religious sentiment, strikingly developed; but a surer indication of a tendency to spiritual abstraction, was expressed in her deep set, intellectual, and rather melancholy eye. Her mouth, when closed, expressed firmness and decision, but, when in play, the gentlest and tenderest of human affections; and the voice that proceeded from it was the organ of her soul, and expressed its divine essence—love. Such was the lady Clotilde—the martyr, who would have been the canonized saint, had she died in the bosom of the orthodox church.

The other female was a girl of sixteen, Rosalie, the daughter of Clotilde, and resembling her in nothing but the purity and spirituality of her expression. Her complexion was of the tint which the vulgar call fair, and the learned Thebans in such matters, brunette; her eyes were the deepest blue, and her eye-lashes long and so black, that in particular lights they imparted their hue to her eyes. Her hair, we are told, was of the color that harmonized with her skin—what that hue was we are left to imagine. Her features, neck, and whole person (the feet and hands are dilated on with a lover’s prolixity) the chronicle describes as cast in beauty’s mould, ‘o

-----

p. 9

that he who once looked on this fair ladye Rosalie saw imperfection in all other creatures.’

Rosalie led, by her hand, a little girl of four years, a cherub in beauty.

‘Why, dear Mama,’ said Rosalie, ‘are you so silent and thoughtful?—and tell me—pray—why were you so cold to our sweet lady queen to-day, when she bade us prepare the fête for the king?—I would not pry into secrets, but when she spake low to you, did she not say something of sad looks not suiting festive days?’

‘She did, Rosalie—nd yet she well knows they are but too fitting. Let us seat ourselves here, my child, and while Zeba looks after Marie I will entrust you with what is better suited to your discretion than your years.’—She beckoned to Zeba to relieve them from the child, but little Marie, a petted favorite of Rosalie’s sprang on the bench and clung around her neck, till she was won away by a promise of a game of ‘hide and go seek,’ among the vines and shrubs.

‘Rosalie,’ continued the mother, pointing to Marie, ‘that child is not the offspring of a union which man deems honorable, and calls marriage, and which it pleases heaven, my child, to authorize to humanity in some stages of its weakness and ignorance, but she is—I hesitate to speak it to your pure ears—the fruit of illicit love.’

‘Mother! what mean you?—She is surely the child of our good lord king and of his wife—our lady Agnés and our queen?’

‘Our lady Agnés de Meran, Rosalie, but not his wife—nor our rightful queen.’

‘You should not have tole me this!—you should not have told me this!’ reiterated Rosalie, covering her eyes from which the tears gushed, ‘I loved her so well!—and Marie!—oh you should not have told me!’

‘My dear Rosalie, I have withheld it as long as I dared.

-----

p. 10

The world to you is as a paradise, and I shrunk from exposing to you the traces of sin and evil that are upon it. But evil—temptation must approach you, and how are you to resist it, if yu know not its existence? Listen patiently, my dear child. There is much in the story of our lady to excuse her with those compromising consciences that weigh sin against temptation; and much to make her pitied by those who weigh the force of temptation against the weakness of humanity.’

‘I am sure I shall pity her,’ interrupted Rosalie.

‘Beware, my child. Pity, the gentlest spirit of heaven, sometimes loses her balance in leaning too far on the side of humanity.’

‘But pity is heaven-born, dear mother.’

Clotilde did not reply, for she had not the heart to repress the instincts of Rosalie’s affections; and Rosalie added, ‘I am sure our lady Agnés has sinned unwittingly.’

‘Alas, my child!—But listen—I must make my tale a brief one. Our royal master, who in his festive hours appears to us so kind and gracious, is stained with crimes, miscalled virtues by his blind guides, and false friends.’

‘Crimes, mother?’

‘Yes, Rosalie, crimes—persecution and murder misnamed, by his uncle of Rheims, zeal—cruelty, rapine, excess, and what I will not name to thy maiden ears. He was anointed king in the blood of his subjects—for les fêtes de la Toussaint, when he was crowned, were scarcely past when, set on by the Archbishop, he commanded his soldiers to surround the synagogues of the Jews, on their Sabbath-day, to drag them to prison, and rob them of their gold and silver to replenish the coffers which his father Louis had emptied for offerings to the church. The Jews hoped it was a passing storm, but the king ordered them to sell all they possessed, and with their wives and little ones to leave his

-----

p. 11

dominions. Their property was sacrificed, not sold, and our royal master received the benedictions of the priests! The next objects of his zeal were the violators of the third commandment—the poor were drowned—the rich paid a fine into the king’s treasury, for as our chronicle of St. Denis hath it, the king holds ‘en horreur et abomination ces horribles sacremens que ces gloutons joueurs de dés font souvent en ces cours, et ces tavernes.’

‘But, dear mother, was he not right to punish such?’

‘To fine the rich, and drown the poor, Rosalie?’—Rosalie perceived that her shield was ineffectual, and her mother proceeded, but not till she had cautiously looked around her. ‘To fill up the measure of his obedience to sacerdotal pride and hatred, he published an edict renewing the persecution against the Patérins.’—

‘the Patérins, mother?’

Clotilde smiled faintly at her daughter’s interrogatory. ‘The name of these much abused people you have not yet heard, for it is a perilous one to speak in our court; but they are the followers of those pious men who, having obeyed the commands of their Lord, and searched the Scriptures, have changed their faith and reformed their morals. They differ somewhat among themselves, having entered into the glorious liberty of the gospel, and being no longer bound to uniformity by the bulls of the Pope or the word of the Priest. They have all been marked by the purity of their lives—a few by their austerity. Some among them eat no meat, and others deem even marriage criminal.’

‘Mother!’ exclaimed Rosalie, in a tone that indicated a revelation had burst upon her.

‘I read your thoughts, Rosalie—yes—I am a Patérin. Here in the very bosom of the court I cherish the faith for which many that I loved were cast into prison, and afterwards ‘made (I quote from our Court Chronicle) to pass

-----

p. 12

through material flames to the eternal flames which awaited them!’ [sic]

‘And was it such as you, my mother,’ asked Rosalie, pressing her cheek to Clotilde’s, ‘that thus suffered?’

‘Such, and far better, Rosalie; and who,’ she added, the ecstasy of faith irradiating her fine countenance, ‘who would shrink from the brief material fire through which there is a sure passage to immediate and eternal glory?’

If there are moments of presentiment when the future dawns upon the mind with all the vividness of actual presence, this was one to Rosalie. She threw her arms around her mother’s neck and said in a trembling voice, ‘God guard my mother!’

‘He has guarded me,’ replied the lady Clotilder, gently unlocking Rosalie’s arms, ‘and while it is best I shall continue like the prophet safe in a den of lions. ‘Take no thought for the morrow,’ Rosalie.—But I have been led far away from my main purpose, which was to give you a brief history of the lady Agnés.

‘Our lord the king had contracted a marriage with Isemburg of Denmark, daughter of Waldemar le Grand. On his progress to receive her, he visited the castle of one of the Duke of Meranie’s adherents, where a tournament was holding. His rank was carefully concealed. He was announced in the lists as le Chevalier affiancé, and his motto was la bonne ‘esperance.’—Our lady Agnés—then in her sixteenth year—just your present age—presided as queen of love and beauty. Philip was thrice victorious, and thrice crowned by the lady Agnés. At the third time there were vehement demands that his visor should be removed. He appealed to Berchtold, the father of our lady, and prayed permission to preserve his incognito to all but the lady Agnés, to whom, if she were attended by only one of her ladies, he would disclose his name and rank. Berchtold allowing that nought

-----

p. 13

should be refused to the brave and all conquering knight, granted the private audience of his daughter, and she selected me from among her ladies to attend her. Philip, affianced to another, and confessing himself bound to keep the letter of his faith, violated its spirit. He declared himself passionately in love with our lady, and vowed eternal faith to her.—Our poor lady, smitten with love, received and returned his vows. The marriage with Isemburg was celebrated four days after.’

‘Was he married to Isemburg?’

‘Yes, if that may be called marriage, Rosalie, which is a mere external rite—where there is no union of heart—where vows are made to be broken.’

‘this surely is most sinful—but not so when hearts as well as hands are joined—think you, mother?’

The lady Clotilde proceeded without a reply to her daughter’s interrogatory. ‘It was told through Christendom that the king of France, on receiving the hand of the beautiful Isemburg, was seen to turn pale and tremble, and shrink from her; and when her rare beauty and her many graces were thought on, there was much marvelling, and many there were who attributed the strange demeanor of the king to sorcery! The lady Agnés and I alone knew the solution of the mystery.—Eighty days after the marriage he appealed for a divorce to Bishops and Archbishops assembled at Compeigne—his own servile tools. The marriage was annuled on a mere pretext, and immediately followed by the outward forms of marriage with our fair lady.’

‘I comprehend not these matters; but, mother, were not the lawful forms observed?’

‘Rosalie! beware how in your tenderness for your mistress you confound right and wrong[.] Priests may not, at their pleasure, modify the law of God. The rules of holy writ are few and inflexible.—Isemburg denied the validity

-----

p. 14

of the divorce, and retired to a convent. The Pope, from worldly policy, has maintained her part. An interdict was lain upon the kingdom. Marriages and interments in consecrated ground were forbidden. Weeping and mourning pervaded Philip’s dominions—all for this guilty marriage. Then followed reconcilliation with the Pope—then fresh animosities and perjuries—and through all Philip has adhered to our lady.’

‘Faithful in that, at least, mother.’

‘Yes, faithful where faith was not due. The lady Isemburg still lives and claims her rights—every true heart in Christendom is for her, and it is only here, in the court of our lady, that her wrongs are unknown, or never mentioned.’

‘And why, my dear mother,’ asked Rosalie, recurring to her first feelings, ‘why, since you have so long kept this sad tale from me, why did you tell it now?’

‘I kept it because that, yet a child in years, it was not essential you should know it, and I could not bear to throw a shade over your innocent and all-trusting love for our lady. Now you are entering on the scene of action yourself. Temptation will assault you from which I cannot shield you. Even your mother, my child, cannot keep your account with your Judge.’

‘Alas, no!—But what temptations have I to fear, dear mother?’

‘You are endowed with rare beauty, Rosalie, and in this court there will be many smooth tongues to tell you this.’

‘They have already told me so,’ said the ingenuous Rosalie, slightly blushing.

‘Who?—who?’ asked her mother.

‘The lord Thièbant, and the young knights Arnold and Beaumont, and the king himself; but indeed, mother, it

-----

p. 15

moved me not half so much as when my lady Agnés commends the manner of my hair, or the fitting of my kerchief.’

‘Ah, Rosalie, these flattering words have been as yet lightly spoken—as it were to a child, but when they are uttered in words of fire, par amour.’

‘Oh, if you fear for me, mother,’ said Rosalie, dropping on her knees, and crossing her arms in her mother’s lap, ‘I will now vow myself to the Virgin.’

‘Will you, Rosalie?’

‘In sooth I will. Not to immure myself within the walls of a convent, shut out from that communion which the Creator holds with his creatures through his visible works; and that still better communion vouchsafed to us when we are fellow-workers with Him in missions of mercy and love to His creatures.’

‘You are somewhat of a Patérin too, my Rosalie, said her mother, rejoicing that her indirect lessons were so definitely impressed on her daughter’s mind. ‘But have you comprehended the perfect spirituality of the Christian’s law? Do you know there is no virtue in external obedience, however self-denying and self-afflicting that obedience may be, if the affections, the desires, the purposes, are not in perfect subjection to the will of God? Do you know that if you now vow yourself to a vestal’s life, it would be sin should you hereafter, even in thought, repent this vow and sorrow for it’

‘But dear mother that cannot be. I can never love another so well as I love you, and our poor lady Agn[é]s—Now therefore, in this quiet Temple of God let me make the vow.’

Clotilde’s face was convulsed with thick coming conflicting thoughts and feelings. In common with many of her sect, she had retained that tenderest and most poetic feature of the Catholic religion, a tender homage for the Virgin. She believed the holy mother would vouchsafe supernatural aid

-----

p. 16

to her vestal followers, and this aid she thought might be essential to one who, with unsuspecting youth, and surpassing beauty, was beset by the changes of a court of which virtue was not the presiding genius. But on the other hand, she feared to take advantage of the inexperience of her child. Her very willingness to assume the shackles, made her mother shrink from their imposition. Rosalie clasped her hands and raised her eyes. ‘Stay my sweet child—not now’ [sic] said her mother—‘a vow like this demands previous meditation, and much communing with your own spirit. I trust you are moved by heavenly inspiration, and if so, the work now begun, will be perfected. In eight days from this we celebrate the marriage of St. Catharine, that marriage which typifies the sacred spiritual union of the perfected saint with the author of her salvation. I have twice dreamed the day had arrived, and marvellous, and spirit-stirring fancies, if they be fancies, have mingled with my dreams. I witnessed the holy marriage. I gazed at the sacred pair, when suddenly, as St. Catharine was receiving the bridal ring, it was you my Rosalie and not the saint, your face was as vivid as it is now to my actual sense, and instead of the pale slender hand of the saint, was your’s, [sic] dimpled, and rose tinted as it now is; but alas! the ring would not go upon your finger. While I marvelled and sorrowed, flames crackled round me, you, the celestial bridegroom, all vanished from my eyes, clouds of smoke rose around me, as I looked up for help, their dense volume collected over my head parted and I beheld a crown as bright as if it were of woven sunbeams, a martyr’s crown.’

‘Dear mother, I like not this dream.’

‘Be not disquieted my child. Our dreams are sometimes heavenly inspirations, but oftener, compounded of previous thoughts and impressions. Martyrdom has ere now been within the scope of my expectations, and that your marriage

-----

p. 17

may be like that of the blessed St. Catharine, is my continual prayer. Look not back, but forward. If it please heaven to strengthen and confirm the good purpose now conceived, on St. Catharine’s Eve you shall make your vow.’

‘So be it, mother, yet I would it were now.’ The ladies were interrupted by a page from the queen who came to summon the lady Clotilde to his mistress’ presence.

Little Marie seeing her favorite at liberty left her attendant and insisted, with the vehemence of a petted princess as she was, that Rosalie should take a stroll with her along the bank of the river. Rosalie, scarcely past childhood herself, felt her spirits vibrate to the touch of her little friend, and they ran on sportively together, followed by the Moorish servant, till they came to the shore, where beneath a clump of trees, overgrown with flowering vines, a bench had been placed to afford a poste restange, which a painter might have selected, as affording, on one side a view of the turrets of the castle, towering above the paradise in which it was embosomed, and on the other, of the windings of the Seine and the picturesque bridge that crossed it. Just before Rosalie arrived at this point of sight, a cavalcade had passed the bridge on their way to the castle—the Archbishop of Rheims and his retinue. One of them had lagged behind the rest, and stopping on the bridge to survey the river, he had caught a glimpse of what seemed to him the most poetic personifications of youth and childhood that his eye had ever rested on. The spectator was mounted on a Spanish jennet, caparisoned with the rich decorations which the knights of the time, who regarded their steeds almost as brothers in arms, were wont to lavish on them. The bridle was garnished with silver bells, so musical that they seemed to keep time to the graceful motions of the animal. It might have puzzled an observer to decide to which of the two great faineant classes that then divided the Christian world, knights,

-----

p. 18

or monks, to assign the rider. Beneath a long monastic mantle, fastened by a jewelled clasp, a linked mailed shirt might be perceived. The face of the wearer had the open gay expression of a preux chevalier, with a certain softness and tenderness that indicated a disposition rather to a reflective, than an active life. He had become wearied of the solemn and silent pomp of the archbishop’s retinue, and had resigned the distinction of riding beside his highness for a gayer companion and a freer position in the rear of the train.

‘By my faith, Arnaud,’ said he. ‘I find these lords, bishops and archbishops very stupid, in propria persona.’—‘Ah, Gervais, had you heeded me! but as the proverb says ‘good counsel has no price.’—‘But my good master priest, we have yet to see whether my hope will not give the lie to your experience.’

‘Bravo!’ retorted Arnaud, laughing louder than one would have dared to laugh nearer the archbishop. ‘St. Catharine’s is the day you doff that mailed shirt of yours, forever? When that day comes round again, we shall see whether dame experience has forfeited a name for speaking truth, and lying hope has gained one.’

‘Holy Mary!’ exclaimed Gervais de Tilbéry, checking his horse as he entered upon the stone bridge. ‘What houri is that!’ ‘Softly, Sir Gervais,’ replied his friend, ‘it is scarcely prudent to utter oaths, and gaze after houri’s [sic] within a bow-shot of my lord archbishop, within seven days of St. Catharine’s Eve! Are you spell-bound, Gervais.’

Gervais heeded not the prudent caution of his friend, but asking him to bid Hubert (his attendant) come to him, he permitted Arnaud to proceed alone. Hubert came. Gervais gave him the horse to lead to the castle.

Hubert disappeared, and Gervais succeeded in scaling the bridge and letting himself down within the paradise that enclosed the houri, whom he approached (unseen by her)

-----

p. 19

through a walk enclosed by tall flowering shrubs. As he issued from it, he perceived his magnet still standing near where he had first seen her, but now in a state of great alarm. The bench, mentioned above, had been taken from its supporters, and one end of it was projecting over the precipitous bank. An eddy in the river had worn away the bank beneath, and the water there was deep and rapid. Little Marie with the instinct which children seem to possess to find, or make danger, run on to the bench, and when Rosalie stepped on to draw her back she darted forward to its extremity, beyond Rosalie’s reach; she perceiving that if she advanced one inch farther the bench would lose its balance and they must both be precipitated into the river. The children perfectly unconscious of danger was diverted at Rosalie’s terror, and clapping her hands and jumping up and down was screaming ‘Why don’t you catch me Rosalie?’ The Moorish girl threw herself on her knees and supplicated the child to come back, in vain. Rosalie was pale and trembling with terror when she felt a firm tread on the bench, behind her, and turning, saw the stranger, who said to her ‘fear not, sweet lady, give me your hand—I am twice your weight—the board will not move—now advance a step and grasp the little girl.’ This was done in an instant, and the mischievous little gipsey [sic] was dragged from her tormenting position. Rosalie after she had kissed and chidden her, bade her return with Zeba to the castle, saying she would instantly follow, and then turned to thank the stranger for his timely interposition. A bright flush succeeded her momentary paleness. It may be that the joy of transition from apprehension to security was enhanced by its being effected by a young and handsome stranger knight, for the young ladies of the middle ages were as richly endowed with the elements of romance as the fair readers of our circulating libraries, who find in many a last new novel but

-----

p. 20

little besides a new compound of the songs of troubadours, and tales of trouveurs.

The thanks given, and most graciously received, Rosalie felt embarrassed by the stranger continuing to attend her. ‘Think me not discourteous, sir knight,’ said she ‘if I apprise you that you are within the private pleasure grounds of our lady queen—sacred to herself and the ladies of her court.’ While Gervais paused for some pretext for lingering, Rosalie kindly added, ‘I know not how you came here, but I am sure you were heaven-directed.’

‘Surely then, fair lady, I should follow Heaven’s guidance, and not leave the celestial companion vouchsafed me.’

‘But,’ asked Rosalie, smiling, ‘is not thy mission accomplished?’

‘It would be profane in me to say so, while I am within superhuman influence.’

‘Well,’ thought Rosalie, ‘since he persist, there is no harm in permitting him to go as far as the grapery—there we must separate.’ Some conversation followed, by which it appeared that the stranger was of the Archbishop of Rheim’s household, and Rosalie asked him ‘if he knew aught of Gervais de Tilbé?’

‘Ay, lady,’ replied Gervais, ‘both good and evil.’

‘Evil? I have heard nought but good of him.’

‘What good can you have heard of one scarce worthy to be named before you?’

‘This must be sheer envy,’ thought Rosalie, but the thought was checked when, glancing her eye at the stranger’s face, she saw a sweet pleasurable smile there. ‘Many,’ she said, ‘have brought us report of his knightly feats, and some, who note such matters, of his deeds of mercy. Our ladies call him the handsome knight, and the brave knight, and the knight of the spotless escutcheon.’

‘Oh, believe them not—believe them not!’ said Gervais, laughing.

-----

p. 21

‘Seeing is believing, saith the musty adage,’ replied Rosalie. ‘Gervais de Tilbéry is coming to the Chateau des Roses with the Archbishop.’

‘And is here, most beautiful lady,!’ cried Gervais, dropping on one knee, ‘to bless heaven for having granted him this sweet version—to ask thy name—and to vow eternal fealty.’

‘Oh, stop—rise, Sir,’ said Rosalie, utterly disconcerted and retreating from Gervais, ‘I am a stranger to thee.’

‘Nay,’ said he, rising, and following her, ‘I care not for thy name, nor lineage—no rank could grace thee—do not, I beseech you, thus hasten from me—hear my vows.’

‘You are hasty, Sir,’ said Rosalie, drawing up her little person with a dignity that awed Gervais, ‘and now I think of it—have I not heard that it was your purpose to enter the church?’

Gervais became suddenly as grave as Rosalie could have wished. ‘It was my purpose,’ he replied, in a voice scarcely audible.

‘Then you are already bound by holy vows.’

‘Not yet—the ceremony of the tonsure is appointed for the festival of St. Catharine.’

‘St. Catharine!’ Rosalie’s exclamation was involuntary. Her own purposed vow recurred to her, and she may be pardoned if she (being sixteen) deemed the coincidence a startling one.

They proceeded together: Gervais, in spite of her remonstrances, attending her through the grapery to the garden gate, where Marie stood awaiting her. ‘Come in Rose—come in,’ said the impatient child, ‘and you, sir stranger, go back—I hate you, and mama will hate you for stealing away my Rose.’ So saying, she shut the gate in poor Gervais’s face, before he had time to speak, or even look a farewell to Rosalie. He had leisure, during his long, circuitous walk to the castle, to meditate on his adventure, to see bright vision

-----

p. 22

of the future, and to decide, if necessary, to sacrifice the course of ambition opened by the Archbishop’s patronage to the attainment of Rosalie. Gervais de Tilbéry was of noble birth; a richly endowed, gay, light-hearted youth, who was guided by his impulses; but, fortunately, they were the impulses of a nature that seemed, like a fine instrument, to have been ordained and fitted to good uses by its author. A word in apology of his sudden passion, and its immediate declaration: In that dark æra when woman was sought (for the most part) only for her beauty, a single view was enough to decide the choice; the wife was elected as suddenly as one would now pronounce on the beauty of a fabric or a statue. Gervais de Tilbéry, for the first time in his life, felt that woman was a compound being, and that within the exquisite material frame, there dwelt a spirit that consecrated the temple.

* * * * * * *

It was on the evening of the day following Rosalie’s meeting with the young knight, that Clotilde was officiating at her daughter’s toilette. She was preparing for a masked ball, where she was to appear as a nymph of Diana. She was dressed in a light green china silk robe, fitted with exquisite skill to a form so vigorous, graceful and agile, that it seemed made for sylvan sports. Her luxuriant hair was drawn, à la Grecque, into a knot of curls behind, and fastened by a small silver arrow. A silver whistle, suspended by a chain of the same material, richly wrought, hung from her girdle. Her delicate feet were buskined, her arms bare. She had a silver bow in her hand, and to her shoulder was attached a small quiver of the finest silver net-work, filled with arrows. After her mother had finished her office of tire-woman, which she would permit none to share with her, and before tying on Rosalie’s mask, she gazed at her with a feeling of pride and irrepressible triumph. A sigh followed this natural swelling of her heart.

-----

p. 23

‘Why that sigh, dear mother?’ asked Rosalie.

‘I sighed, my child, to think how little you appear in this heathen decoration, like a promised votary of the blessed Virgin.’

‘Not promised,’ replied Rosalie hastily, and blushing deeply.

‘Not quite promised, my child, but meditated.’

‘Mother,’ said Rosalie and paused, for the first time in her life hesitating to open her heart to her parent; but the good impulse prevailed, and she proceeded. ‘Mother, in truth the more I meditate on that, the less am I inclined to it.’

‘Rosalie!’

‘It is true, dear mother; and is it not possible that you directed me to defer the vow in obedience to a heavenly intimation?—I have thought it might be so.’

Clotilde fixed her penetrating eye on Rosalie’s. ‘There is something new in your mind, Rosalie; keep it not back from me, my child; be it weakness or sin, I shall sorrow with, not blame you.’

‘It may be weakness, mother, but I am sure it is not sin. I told you of my meeting with Gervais de Tilbéry, in la Vigne.’

‘Yes, and of his rescuing our little Marie, but else nought.’

‘There was not much else—and yet his words and looks, and not my vow to the Virgin, have been in my mind ever since.’ Rosalie, after a little stammering and blushing, gave her mother a faithful relation of every particular of the meeting, and though she most dreaded her mother’s comments on that part of her story, she did not disguise that Gervais was destined for holy orders.

Her mother embraced her and thanked her for her confidence. ‘Dear child,’ she said ‘forwarned, I trust you will be forearmed. This young Gervais will see no barrier to his pursuit of you in the holy vows he assumes. The indulgence and absolutions of our corrupted church license all sin; but we are not thus taught of the Scriptures, whose spiritual

-----

p. 24

essence has so entered into our hearts that we believe marriage, even performed with all holy ceremony and legal rites, is not permitted to the saint, albeit allowed to human infirmity.’

‘I always believe what you say to me, mother; yet’—

‘Yet—speak freely, Rosalie.’

‘Yet it does seem to me incomprehensible, that the relation should be wrong, from which proceeds the tie that binds you to me and me to you; that opens a fountain of love that in its course is always becoming sweeter and deeper—hark! the bell is sounding—I must hasten to the queen’s saloon—tie on my mask, and be assured no mask shall ever hide a thought or feeling from you, my mother.’

‘Go, my sweet child, remember pleasure enervates the soul, and be watchful—I remain to pray for you.’

* * * * * * *

How did the aspect and the spirit of the scene change to Rosalie, from the quiet apartment of her saintly mother, to the queen’s saloon brilliantlly illuminated, filled with the flower of French chivalry and with the court beauties, whom the lady Agnes, [sic] either from a real passion for what was loveliest in nature, or to show how far her conjugal security was above all envy, delighted to assemble about her in great numbers. She was seated at the king’s right hand, under a canopy of crimson and gold. The king was in his royal robes, and both he and the lady Agnes [sic] were without masks. She was dressed in the character of Ceres, and her rich and ripened beauty personified admirably the Queen of Summer. Her crown (an insignia which, probably from her contested right to it, she was careful never to omit,) was of diamonds and gold, formed into wheat-heads, the diamonds representing the berry, and the gold the stem and beard. Her robe was of the finest Flanders cloth, glittering with embroidery, depicting the most productions of the earth which, as her ample train

-----

p. 25

followed her, seemed to spring up at her tread. The young Philip sat at his father’s feet on an embroidered cushion, Marie at her mother’s, both personifying Bacchantes. The ladies of the court, in the costume of nymphs, muses, and graces, were at the queen’s right hand; the lords and knights, in various fantastical characters, at the king’s left. It was suspected, from several persons wearing the symbols of a holy profession, that the Archbishop’s party was present, but as he was precise in observances, and severe to cruelty in discipline, none ventured to assert it. Rosalie was met at the door by one of the appointed attendants, and led to the lady Agnes’ side, a station always assigned her as the favorite of her mistress. ‘Ah, my little nymph of the chase,’ said the queen, as Rosalie knelt at her feet and laid down her bow in token of homage, ‘you are a rebel to-night; what has Ceres to do with Diana’s followers?’ ‘True,’ said a young knight who had a pilgrim’s staff in his hand, ‘one is the bountiful mother, and the other the nun of mythology—more unkind than the nun, for she does not immure the charms which it is profanity to admire.’

‘Gervais de Tilbéry,’ thought Rosalie, instantly recognising his voice, ‘your words seem to me prophetic.’

‘There is no false assumption in this character of yours,’ continued the pilgrim knight, ‘for the arrow loosed from thy bow is sure to pierce thy victim’s heart.’

‘Hush all!’ cried the queen. ‘Our minstrel begins, and our ears would drink his strain, for his is the theme welcomest and dearest.’

Philip Augustus, as in some sort the founder of the feudal monarchy, has made an epoch in history. His reign seemed to his subjects to revive the glorious era of Charlemagne. It was the dawn of a brilliant day after a sleep of four centuries. He enlarged and consolidated his dominions. France, till his reign had been divided into four kingdoms, of which that

-----

p. 26

governed by the French king was the smallest. He made a new era in the arts and sciences. He founded colleges and erected edifices which are still the pride of France. Notre Dame was reconstructed and enlarged by him. He conveyed pure water by aqueducts to the city of Paris, and in his reign that city was first paved and redeemed from a pestilential condition. His cruelties, his intolerance, and his infidelities were the vices of his age. His beneficent acts were a just theme of praise, but that which made him an inspiring subject to his poet laureate minstrel was his passion for chivalric institutions, his love of the romances of chivalry, and the patronage with which he rewarded the inventive genius of the Trouvéres. ‘In truth,’ says his historian, ‘it was during his reign that this brilliant creation of the imagination, (chivalry,) was in some sort complete.’—The court minstrel, with such fertile themes, sung long, and concluded amidst a burst of applause.

The dancing began, and again and again the pilgrim knight was seen dancing with Diana’s nymph.

‘Ah, Gervais!’ whispered a young man to him, ‘this I suspect is your houri. A dangerous preparation this for your canonicals.’

‘Why so, Arnaud? Do angels never minister to priests?’

‘Never, my friend, in such forms,’ replied Arnaud, laughing.

‘Then heaven forfend that I should be a priest!’

A Dominican friar, in mask, approached Gervais and said in a startling voice, ‘Thou art rash, young man—thou hast lain aside thy badge of sanctity,’ alluding to his pilgrim’s staff.

‘What signifies it, good friar,’ replied Gervais, ‘if I part with the sign, so long as I retain the thing signified? I am not yet a priest.’

‘Have a care, sir,’ replied the friar, in a tone that indicated he was deeply offended by Gervais’s slur upon the priesthood,

-----

p. 27

‘speak not lightly of the office that hath a divine commission!’

‘And assumes divine power, good master friar!’

The friar turned away, murmuring something of which Gervais heard only the words ‘edged tools.’ His mind was full of other matters, and they would have made no impression, had not his friend Arnaud whispered to him, as soon as the friar was again lost in the crowd, ‘Are you mad, Gervais? Knew you not the Archbishop?’

‘The Archbishop!—in that humble suit, how should I?—‘N’importe,’ added the gay youth, after a moment’s panic, ‘the devil, as the proverb says, must hear truth if he listens.’

‘And the proverb tells us too, to ‘bow to the bush we get shelter from.’ ’

‘My thanks to you, Arnaud. I have changed my mind, and shall not seek the bush’s shelter.’

‘Then beware! for that which might have afforded shelter, may distil [sic] poison.’

‘Away with you and your croaking, Arnaud. This night is dedicated to perfect happiness, and you shall not mar it.’

‘Alas, my friend!—the brightest day is often followed by the darkest night.’

But Gervais heard not this word or prophecy. The dance was finished, and he was leading off his beautiful partner. She permitted him to conduct her through the open suite of apartments, each one less brilliantly illuminated than the last, till they reached an apartment with a single lamp, and one casement window which opened upon a balcony that overlooked the garden. The transition was a delicious one from the heated and crowded apartments, to the stillness of nature, and moonlight—from the stifling atmosphere to the incense that rose from the unnumbered flowers of the garden beneath them. Rosalie involuntarily threw aside her mask, and disclosed a face, lit as it was by the sweet emo-

-----

p. 28

tions and enthusiasm of the occasion, more beautiful than the memory and imagination of the enraptured lover had pictured it. It was a moment when love would brook no counsel from prudence; and Gervais, obeying his impulses, poured out his passion in a strain to which Rosalie, in a few, faintly spoken words, replied. The tone and the words sunk to the very depths of Gervais’ heart, assuring him that he was beloved.

An hour flew, while to the young lovers all the world but themselves seemed annihilated—then followed the recollection of certain relations and dependencies of this mortal life. ‘My first care shall be,’ said Gervais, ‘to recede from this priesthood.’

‘Thank kind heaven for that,’ replied Rosalie. ‘As they say in Provence, ‘any thing is better than a priest.’ ’

The lovers both fancied they heard a rustling near them. They turned their heads, and Gervais stepped within the embrasure of the window. ‘It is nothing—we are unobserved,’ he said, returning to Rosalie’s side. ‘But tell me, my Rosalie, (my Rosalie!) where heard you this Provence scandal?’

‘From my dear mother, who spent her youth at the court of the good Raymond.’

‘St. Denis aid us! I believed Trères Gui and Regnier had plucked up heresy by the roots in Languedoc. Heaven forbid that she be infected with heresy!’

‘I know not what you call heresy, Sir Gervais de Tilbéry, but my dear mother drinks at the fountain of truth, the scriptures, and receives not her faith from man, be he called bishop, archbishop, or pope.’

‘By all the saints, I believe she has reason in that. But, dear Rosalie, we will eschew heresy—it is a thorny road to heaven, and we will keep the safe path our fathers have trodden before us, in which there are guides who relieve us of all the trouble of self-direction—will we not?’

-----

p. 29

‘My mother is my guide, Sir Gervais.’

‘So be it, my lovely Rosalie, till her guidance is transferred to me—and thereafter you will be faithful to God, St. Peter, and the Romish Church? And when shall your orthodoxy begin—on St. Catharine’s Eve?’

‘I know not—I know not. All these matters must be referred to my dear mother and the queen. Rise, Sir Gervais, (her lover had knelt to urge his suit)—we linger too long here.[’] Again there was a sound near them, and Gervais sprang forward to ascertain whence it proceeded—Rosalie followed him, and they both perceived the figure of the friar crossing the threshhold of the next apartment. ‘Could he have been here?’ exclaimed Gervais—‘he might have been hidden behind the folds of this curtain—but would he?’

Gervais paused.—‘Whom do you mean?’

‘The friar,’ answered Gervais, warily, for he feared to alarm Rosalie by the intimation of the possibility that the Archbishop of Rheims had overheard their conversation.

Rosalie did not sleep that night till she had confided all, without the reservation of a single particular, to her mother. The lady Clotilde grieved that she must resign her cherished dearest hope of seeing Rosalie self-devoted to a vestal’s life, but true to her spiritual faith that all virtue and all religion were in the mind, and of the mind, she would not persuade—she would not influence Rosalie to an external piety.

She saw much advantage would result to Rosalie from an alliance with Gervais. It would remove her at once and forever from the contagion of the court atmosphere—from lady Agnés’ influence, so intoxicating to a young and confiding nature. Gervais was of noble rank and fortune, and wen that distinction was almost singular among the young nobles of France, he was distinguished for pure morals. ‘It is possible,’ thought Clotilde, as she revolved in her mind all the good she had heard of him, ‘that the renovating Spirit

-----

p. 30

of Truth has already entered his heart. It has not pleased heaven to grant my prayer, but next best to what I vainly asked, is this union of pure and loving hearts.’ The ingenuous disclosure Rosalie had made, awakened in her ind a vivid recollection of a similar experience of her youth, and produced a sympathetic feeling that perhaps, more than her reason, governed her decision. Rosalie that night fell asleep on her mother’s bosom with the sweet assurance that her love was authorized.

The next was a busy, an important, and a happy day to the lovers. ‘Time trod on flowers.’ Alas, the periods of perfect happiness are brief, and one might say with the fated Moor—

‘If it were now to die

’Twere now to be most happy; for I fear

My soul hath her content so absolute,

That not another comfort like to this

Succeeds in unknown fate.’

Every thing seemed to go well and as it should. The Archbishop, with a gloomy brow, but without one comment or hesitating word, acquiesced in Gervais’ relinquishing his purpose of entering the church. The lady Agnés, loath to part with her favorite, yet graciously gave her consent, and persuaded the king to endow the young bride richly, and even the little Marie, though she at first stoutly and with showers of tears, refused to give up her own Rose, yet was at last brought over to the party of the lovers, by the promise of officiating as Bridesmaid on St. Catharine’s Eve.

* * * * * * *

Would that we could end our tale here; but the tragic truth which darkens the page of history must not be suppressed.

The Archbishop of Rheims was devoted to the aggrandizement of his own order—to extending and securing the

-----

p. 31

dominion of the priesthood. His faith might be called sincere, but we should hardly excuse that man who, having been born and educated in a dark room, should spend his whole life in counteracting the efforts of others to communicate the light of heaven to him, and in stopping the little crevices by which it might enter. He was ready to grant any indulgence to errors, or even vices, that did not interfere with the supremacy of the church. He was the uncle of Philip, and, contrary to his inclination, he had been induced by that powerful monarch to countenance him in his rejection of the queen Isemburg, and had thereby involved himself in an unwilling contest with Innocent III. This pontiff, whose genius, his historian says, ‘embraced and governed the world,’ was equally incapable of compromise and pity. He had, a few years antecedent to the events we have related, proclaimed the first crusade against the Albigeois, and had invested the dignitaries of the church throughout Chistendom with the power ‘to burn the chiefs (of the new opinions) to disperse their followers, and to confiscate the property of all that did not think as he did. All exercise of the faculty of thinking in religious matters was forbidden.’ The Archbishop of Rheins was eager to wipe out his offences against the head of the church by his zealous cooperation with him in this persecution. As has been seen, he was nettled by Gervais’ contemptuous hit at the priesthood. It was an indication that the disease of heresy had touched even the healthiest members of the spiritual body, as the general prevalence of corresponding symptoms announced the approach of a wide wasting epidemic. He became restless and uneasy, and, in wandering alone through the apartments of the chateau, he had found his way to the window of the balcony occupied by our lovers, just in time to hear poor Rosalie’s betrayal of her mother. He devoted the following day to a secret inquisition into the life and conversation

-----

p. 32

of Clotilde. He found that she had long ceased to be a favorite of the lady Agnés, who tolerated her only on account of her daughter, and who felt somewhat the same aversion to her (and for analogous reasons) that Herodias cherished against John the Baptist. This feeling of the lady Agnés was rather discerned by the acute prelate than expressed by her, for there was not a fault of which she could accuse the pure and devout woman. Her offences were the rigid practice of every moral virtue. Her time and her fine faculties were all devoted to the benefit of her fellow creatures, so that she fell under the common condemnation, as set forth by a contemporary writer. ‘L’esprit de mensonge, par la seule apparence d’une vie rette, et sans tache, soustrayoit ces imprudens à la vérìté.’ Besides this, she was found deficient in the observance of the Romish ritual, and she ate no meat.

This last sin of omission, being in accordance with the practice of the strictest among those early reformers, was an almost infallible sign of heresy; and on the day following the arrangements for Rosalie’s marriage, the lady Clotilde was summoned before the Archbishop and a council of priests. Her guilt was assumed, and she was questioned upon the several points of the prevailing heresy. We cannot go into details. Our story has already swelled beyond due bounds. The lady Clotilde, unsupported and alone, answered all the questions of her inquisitors, with a directness, simplicity, a comprehension of the subject, and a modesty, that, as a cotemporary chronicler confesses, astounded all who heard her. But it availed nought. She was convicted of denying the right of the Romish church to grant indulgences and absolution, and, in short, of wholly rejecting its authority[.] The Archbishop condemned her as deserving the penalty of death, and the pains of everlasting fire, but he offered her pardon upon a full recantation of her errors.

‘I fear not him who only can kill the body,’ she replied.

-----

p. 33

with blended firmness and gentleness, ‘but Him who can destroy both soul and body, and to Him,’ she added, raising her eyes and folding her hands, ‘I commend that spirit to which it hath pleased Him to vouchsafe the glorious liberty of the gospel.’ Her celestial calmness awed her judges—even the Archbishop hesitated for a moment to pronounce her doom, when a noise and altercation with the guard was heard at the door. It opened, and Rosalie rushed in, threw herself into her mother’s arms, and all natural timidity, all fear of the tribunal before which she stood, merged in one overwhelming apprehension, she demanded, ‘what they were doing, and why her mother was there?’

‘Peace, rash child!’ answered the Archbishop. ‘Shame on thy intrusion—know that thy mother is a convicted heretic.’

‘What wrong has she ever done? Who has dared to accuse my mother?’ cried Rosalie, still clinging to Clotilde, who in vain tried to hush and calm her.

‘Who was her accuser?’ retorted the Archbishop, with a cruel sneer—‘dost thou remember, foolish girl, who revealed the source of the Province scandal?’

The recollection of the sound she had heard during her fatal conversation with Gervais in the balcony, at once flashed upon Rosalie. She elevated her person, and, stretching out her arm towards the Archbishop, exclaimed, with ineffable indignation, ‘Thou wert the listener!’

For an instant his cheeks and lips were blanched with shame, and then stifling this honest rebuke of conscience, he quoted the famous axiom of Innocent III.—‘Dost thou not know, girl, that ‘it is to be deficient in faith, to keep faith with those that have no faith?’—Stand back, and hear the doom of all those who renounce the Romish church.’

‘Pronounce the doom, then, on me too!’ cried Rosalie, kneeling and clasping her hands. ‘I too renounce it—I hate

-----

p. 34

it—I deny all my mother denies—I believe all she believes.’

‘Oh Rosalie!—my child!—my child!’ exclaimed her mother. ‘My lord Archbishop, she is wild—she knows not what she says.’

‘Mother, I do!—have you not taught me?—have we not prayed and wept together over the holy gospels, so corrupted and perverted by the priesthood?’

‘Enough!’ said the Archbishop—‘be assured we will not cut down the dry tree, and leave the green one to flourish.’

‘Thanks!—then we shall die together,’ said Rosalie, locking her arms around her mother’s neck. The delirious excitement had exhauted her—her head fell on her mother’s bosom, and she was an unconscious burden in her arms. Clotilde laid her on a cushion at her feet, and knelt by her while the Archbishop, after a few words of consultation, doomed the mother and daughter ‘to pass through material to immaterial flames,’ on St. Catharine’s day.

They were together conveyed to a dungeon appertaining to the chateau.

* * * * * * *

St. Catherine’s Eve arrived. The hour that had been destined for Rosalie’s bridals found her in a dungeon, seated at her mother’s feet, her head resting on her mother’s breast, and her eyes fixed on her face, while Clotilde read by the light of their lamp the fourteenth chapter of St. John. She closed the book. The calmness that she had maintained till then forsook her. She laid her face to Rosalie’s, and the tears from her cheeks dropped on her child’s. ‘Oh!’ she exclaimed, nature subduing the firmness of the martyr, ‘it is in vain! I read, and pray, and meditate, but still my ‘heart is troubled’—the spirit is not willing.’

‘Dear mother!’ cried Rosalie, feeling as if the columns against which she leaned were tottering.

-----

p. 35

‘My child, it is not for myself I fear or feel. My mission on earth is finished—and I have an humble, but assured hope, that my Saviour will accept that which I have done in his service. For me death has no terrors. I should rejoice in the flames that would consume this earthly tabernacle and set my spirit free; but oh, my child!’ She closed her eyes as if she would exclude the dreadful vision, ‘when I think of thy sweet body devoured by elemental fire my heart fails. I am tempted, sorely tempted. I fear that in that hour I shall deny the faith, and give up heaven for your life.’

‘Mother, mother, do not say so. I hoped it was only I that had sinful thoughts, and affections binding me to earth.’ The weakness of nature for a moment triumphed over the sublime power of religion, and the mother and child wept, and sobbed violently.

So absorbed were they in their emotions that they did not hear the turning of the bolts of their prison, nor were they conscious of any one’s approach till Rosalie’s name was pronounced in a low voice; when they both started and saw, standing before them, Gervais de Tilbéry, the lady Agnés and her confessor. Gervais threw himself on his knees before Rosalie, took her hand and pressed it to his lips. She returned the pressure, but spoke not.

‘There is no time to be lost my dear friends,’ said the lady Agnés. ‘Clotilde,’ she continued, ‘I have vainly begged the boon of your life—it is denied me—but your child’s—yours—my own dear Rosalie, I can preserve. It boots not now to say by what means I shall effect it.’

‘Can she live,’ cried Clotilde vehemently, ‘without renouncing her faith? without denying her Lord?’

‘Without any condition but that she now give her hand to Gervais de Tilbéry—the priest is ready.’

‘Oh tempt me not! tempt me not,’ exclaimed Rosalie,

-----

p. 36

throwing herself on her mother’s bosom. ‘I will not leave her. I will die with her.’

‘Hear me my child,’ said her mother in a voice so firm, sweet, and tranquilizing that it spoke peace to the storm in Rosalie’s bosom. ‘Hear me. I have already told you that for myself this dispensation has no terror, but my spirit shrinks from your enduring it—spare me, my child. God has condescended to my weakness and opened for you a way of escape—do you still hesitate? On my knees Rosalie I beg you to live—not for Gervais—not for yourself—for me—for your mother—give me your hand.’ Rosalie gave it. ‘Now God bless thee my child—shield thee from temptation and deliver thee from evil!’ She put Rosalie’s hand into Gervais’ and bidding the priest do his office, she supported her child on one side while Gervais sustained her on the other. Rosalie looked more like a bride for heaven than earth, her face as pale as the pure white she wore, and her lips faintly, and inaudibly, repeating the marriage vows.

As the ceremony proceeded, her mother whispered again, and again, ‘courage my child! courage! It is for my sake Rosalie.’ The priest pronounced the benediction. Rosalie had lost all consciousness. Her mother folded her in one fond, long protracted embrace, and then, without one word, resigned her to Gervais.

The lady Agnés signed to the priest. A female attendant appeared. Rosalie was enveloped in a travelling cloak and hood and conveyed out of the prison. Clotilde remained alone. We may say, without presumption, that angels came and ministered to her.

We have only to add the conclusion of the contemporary record. ‘One of the condemned escaped from punishment, and it is maintained that she was carried off by the devil; the other without shedding a tear or uttering a complaint submitted to death with a courage that equalled her modesty.’

-----

Robt. W. Weir pinxt. James Smillie sculpt.

Bourbon’s Last March,

(Halt at La Riccia).

Printed by R. Andrews.

-----

[p. 37]

BOURBON’S LAST MARCH.

BY G. C. VERPLANCK.

[My friend Weir was at work upon a very pleasing landscape of a picturesque scene not far from Rome, from a sketch made by himself whilst studying in Italy. It was the town of La Riccia, better known to scholars and antiquaries as the Aricia of Horace, where he made his first resting place after leaving Rome on his journey to Brundusium.

Egressum magnâ me accepit Aricia Româ,

Hospitio modico.

It occurred to me that the picture would gain much additional interest by the introduction of some historical figures, or a story connected with the scene. The march of the Constable Bourbon to Rome happening to suggest itself to my mind, I recommended that subject to the artist as a suitable accessary to his landscape. He adopted my suggestion and executed it with his usual taste and effect. When therefore, the picture was to be engraved for the decoration of the annual, I could not refuse the painter’s claim in return upon me for a literary illustration of his work. This I have endeavored to give by throwing the story of the last days of the Constable Bourbon into the form of a dialogue or dramatic sketch. I have made little effort at invention, but have aimed at giving as much as I could of facts, incidents, and even minute details, as furnished by the almost contemporary historians, Brantome and the author of the Sacco di Roma, and I have interwoven as many characteristic particulars as the space allowed me would permit. The auto-biography of the eccentric and versatile Cellini furnished other materials, ample and rich enough for a volume instead of the few pages with which I have been obliged to content myself. All the characters, as well as the incidents, are drawn from history.

G. C. V.

-----

p. 38

Part First. Personages Charles Duke of Bourbon, formerly Constable of France, now the commander-in-chief of the Imperial army in Italy. Philibert de Chalons, Prince of Orange, a young nobleman of French descent, now an officer of high rank in the imperial servies. Pomperan, the confidential friend of Bourbon and companion of his flight from France. Jonas, an old Gascon captain of high military reputation. Cabrera, D’Avallos, [a]nd others, Spanish officer.

[Scene First. The neighborhood of La Riccia, twelve or thirteen miles from Rome. The town and castle crowning a hill, along the foot of which runs the ancient Roman road, the Via Appia; an extensive view, to the east, of the Campagna di Roma, a level country reaching to the mouth of the Tiber, which is seen in the distance. The army of the Duke de Bourbon is winding through the valley to the south of La Riccia, in the van a large body of Spanish cavalry, knights mounted, and men-at-arms, in the midst of whom ride the Duke and the Prince of Orange by his side. At their hed a mounted trumpeter, and a man-at-arms, bearing a furled standard, followed by Pomperan, and Captain Jonas, and Spanish officers. Time. Good Friday, the 3d of May, 1527.]

Jonas. So, Sieur de Pomperan, we are now upon the old road leading direct to Rome. What means this? I had given up all thoughts of seeing the holy city, this blessed Easter. If fasting will fit us for keeping Easter at Rome, St. Paul knows we have had a strict enough Lent of it; and for to-day never anchorite kept the holy fast more rigidly than we poor fellows have done. But I had thought that the Duke meant to end our long Lent and find us quarters and good cheer at the enemies’ expense further south. But this sudden detour looks—tell me Sieur de Pomperan what it means.

Pomperan. The Duke is his own counsellor and a

-----

p. 39

safe and a wise one he is. In due time we shall all know whither we are bound, and quite time enough, too, to enable us all to do our duty like gentlemen and soldiers.

Jonas. You say right. It is no business of ours, where we were going. The Duke will take good care of us. He is as secret as Hannibal, the Carthagenian, as rapid and bold as Scipio, and as gentle and cocurteous a knight as Julius Cæsar himself. So says your Spanish camp song, and it says true. Let Cæsar and the other old fellows be quiet and give way to the fame of our Bourbon.

Cabrera and D’Avallos. Aye, aye.

(They sing in a sort of ballad chant.)

Calla, calla Julio Cesar, Hannibal y Scipion

Viva la fama de Bourbon.

The cavalry, officers and soldiers, join in the chorus, Viva la fama de Bourbon, which is repeated by troop after troop along the whole line of march, until the whole army appear to join in it.

Pomperan to Cabrera. But why do you not give us the new stave that the Duke himself made the other day when we were all growling and snarling about our misery and poverty as we were crossing the Appenines in a snow storm. How does it go captain?

Jonas. Me, do you ask me, how should I recollect your Spanish ditties. I am not like the Duke or the Emperor Charles. I cannot jabber a new language after a week’s study. I have been living among these Spaniards these six years, and none of the block-heads have learnt my language. Why do you expect me to know more of them than I am obliged to. I can give

-----

p. 40

a word of command, or ask forr bread, meat and wine, in Castilian, and that is all. But if you want a stave in the tongue of Oc, the beautiful language of Provence and Languedoc, I am your man; I will sing you my last roundelay.

Pomperan. Not now; but, Cabrera, let us have that stanza of the Duke’s which he added to our Spanish camp songs the other night, during our cold arch over the mountain. I mean that in which he says he is as poor a gentleman as any of us, without a single ducat in his pocket.

Cabrera. And well might he say so, has he not distributed among us all his money, jewels, plate, wines, provision, clothes, every thing but his own arms and two chargers. There is no fiction in his poetry, strike up D’Avallos.

D’Avallos sings.

Deziales mis Señores, yo soy

Pobre Cavallero

Y tanbien como vos otros no tengo

Un dinero.

Chorus of Spanish cavalry; ‘Deziales mis Señores,’ etc. ending with Viva la fama de Bourbon.