Peale’s Museum, from

The Child’s First Book of History

by

Samuel Goodrich (1832)

Charles Willson Peale founded his museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in

1786. It contained an eclectic collection of natural history specimens,

portraits of admirable historical figures, and human artifacts from various

countries—all intended to edify visitors and to show the place of human

beings as part of the animal kingdom.

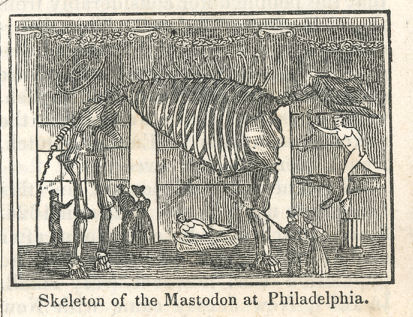

His most famous display, however, was the mastodon skeleton he obtained in

1801. Eleven feet high at the shoulder and fifteen feet from chin to rump,

it was huge and strange and confusing: was it

carnivorous?

Was it an elephant? If so, what were elephants doing in North America?

There were a lot of questions to be answered about the “Great American

Incognitum.”

So it’s no wonder that when

Samuel Griswold Goodrich

described Philadelphia in The Child’s First Book of History, he

included a brief description of the museum and a picture of the mastodon

skeleton on display. In his quest to provide entertaining and educational

books for children,

he quickly realized that those books needed to be illustrated. This was

especially important when describing something like the mastodon, so bizarre

that young readers would have difficulty visualizing it.

Other

writers

had included mammoths or mastodons in their works, but Goodrich managed to

show what they looked like.

Well, sort of. The image is tiny (two inches wide and 1.5 inches tall) and

the skeleton is almost lost in the background. It’s tuskless, and, to the

modern reader, the head is oddly misshapen. But the illustration certainly

gets across its point: the skeleton is huge—the human visitors barely reach

the first leg joint—and it’s evidently part of a wide-ranging collection.

What appears to be a stuffed alligator (or crocodile) is suspended in the

background, with two statues (a message-bearing Hermes and a Roman sarcophagus)

nearby. The “windows” in the back may be the display of taxidermied

birds in a self-portrait Peale painted of himself standing in his museum. Was the

illustration wholly accurate? Probably not. But it’s a charming visualization of

the major themes of Peale’s museum: education and variety.

Illustrators need models to work from, and those illustrating

early works on fossils were no

different. The skeleton pictured here greatly resembles

one drawn by Titian Ramsay

Peale II, which appeared in American Natural History, by John D.

Godman (1826-1828).

Strange as the skeleton looks, the illustration is fairly accurate. The

head is flat on the top because the top of the skull hadn’t yet been

discovered. But where are the tusks? Tusks seem to have puzzled

naturalists of the time; there were arguments that the tusks curved up, like

those on elephants, and there were arguments that the tusks curved down, so

the mastodon could dig for mussels (and a wood engraving by Alexander

Anderson appears to have the tusks inserted in the eye sockets). Leaving off

the tusks may have seemed the safest option.

Illustrations were expensive to produce, and publishers made sure to

get their money’s worth by reusing the

engraving blocks. Goodrich was no different: this little wood block

found its way into

The Child’s Own Book of American Geography

(1832) and—thanks to some creativity—in

Peter Parley’s Tales about the State and City

of New York (1832).

My copy is of the 1832 edition.

(Dimensions of the skeleton are in Stanley Hedeen’s Big Bone

Lick: The Cradle of American Paleontology [Lexington, KY: The

University Press of Kentucky, 2008], p. 85. Information about research on

the mastodon and the tusk controversy appears in Paul Semonin’s American

Monster: How the Nation’s First Prehistoric Creature Became a Symbol of

National Identity [New York: New York University Press, 2000].)

http://www.merrycoz.org/books/Goodrich/PPHist1/PEALE.xhtml

Peale’s museum, from The Child’s First Book of History, by Samuel Griswold Goodrich. (Philadelphia: Key, Meilke, and Biddle; Boston: Richardson, Lord, & Holbrook, 1832; p. 58)

CHAP. XXIX.

STATE OF PENNSYLVANIA.

1. This is a large, wealthy and flourishing State. Our

travels through it will afford us much gratification. We must examine

Philadelphia in the first place. In my opinion, it is the handsomest city

in the United States. The streets are all straight, and cross each other in

a regular manner.

2. We shall find many interesting objects in the city.

The Bank of the United States is built of white marble, and is one of the

most beautiful edifices in the world. The Arcade is a very curious

building, in which there are a great many shops. In the upper part of this

building is Peale’s Museum.

3. This is a most interesting collection. There are

hundreds of stuffed birds and animals, which look as if they were really

alive. There are grisly bears, and deer, and elk, and prodigious great

serpents, and birds with beautiful feathers, and cranes, with legs as long

as a man; and there are bugs and butterflies, and Indian tomahawks, and a

multitude of other things.

4. But the most wonderful of all is the skeleton of the

Mastodon, or Mammoth. These bones were found in the State of New York; the

animal to which they belonged must have been as large as a small house. No

animals of this kind now live in America, or anywhere else. But long before

the white people came to this country, it is certain that they roamed

through the forests of America. Some of them must have been at least four

times as large as the largest elephant.