Double Vision: Recycling Illustrations in 19th-Century American Magazines

[More examples]

Early periodicals often reprinted articles and poems that originally had appeared elsewhere: Fanny Fern’s success was assured when her first article was reprinted immediately in several other periodicals. Images were no exception. Illustrations sometimes appeared in several works: The Book of One Hundred Pictures (Philadelphia: American Sunday School Union, 1861) reprinted at least one illustration from Stories by Jack Mason; and The Good Scholar used two of the illustrations which had appeared in the ASSU book. Robert Merry’s Museum and the Youth’s Companion shared tastes—and illustrations. (Ironically, the Museum merged with the Companion in 1872.) Sometimes the image was altered to mesh with the piece it accompanied.

The images on this page appeared in the Youth’s Companion—and in other magazines. Until the late 1860s, the Companion rarely featured more than one illustration per issue. Merry’s Museum featured more, but few were engraved especially for the magazine—or for any children’s magazine, for that matter. An illustration of “Grandfather’s Wig,” published in 1829, in Samuel Goodrich’s Peter Parley’s Winter Evening Tales was the frontispiece for the July/August 1832 issue of The Juvenile Miscellany. In 1867, The Little Corporal printed engravings of four Rogers Groups: “After looking everywhere for illustrations peculiarly appropriate to the pages of The Little Corporal—pictures which should be purely American, and worthy of the admiration of all Americans—we have determined to have an engraving of one of these unsurpassed Groups in each number of our paper ….” Not only was each the only large engraving to appear in the issue, but it afforded an opportunity to advertise these “statuettes … made from composition which will bear careful washing with soap and water,” which could be ordered in Chicago from William Goodsmith & Co.; Goodsmith and John Rogers thus exploited an advertising venue, and the Little Corporal had a ready source of attractive engravings.

http://www.merrycoz.org/double/DOUBLE01.xhtml

This image was sent to readers of

Robert Merry’s Museum in December 1841, to be used as a frontispiece when the issues for that year were bound. (Accompanying it was a

delightful paean to squirrels which may have been inspired by the gift of a live squirrel to editor

Samuel Goodrich.) The red border was printed in black when the picture was reprinted in volumes apparently created for sale later.

This image appeared on the first page of the May 3, 1855 issue of Youth’s Companion, above a brief piece titled “The Gray Squirrel” which describes what good pets squirrels make and how unpopular they were with farmers. (The engraving seems to have been a bit too large for the space allowed on the page.)

This popular squirrel also leaped into the December 1857 issue of

The Youth’s Casket, as a full-page illustration for a brief piece on the gray squirrel.

This image appeared on the first page of the May 10, 1855 issue of Youth’s Companion, above a brief piece titled “The Newfoundland Dog” which describes how useful they are as labor animals in Newfoundland. (The engraving was given a bit more space on the page than was the engraving of a squirrel printed a week earlier.)

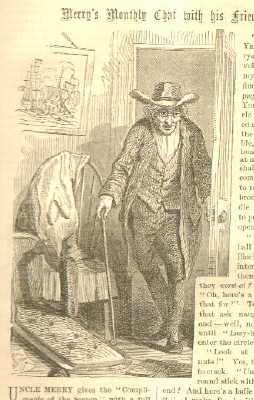

This image appeared on the first page of the December 19, 1861 issue of The Youth’s Companion, to illustrate a piece called “Holiday Times” on the issue’s second page. It’s a piece with a moral: “Grandfather Thomas,” who always tells visiting children to “Go where you like—do what you like, and say what you like”—and who also insists they “don’t do any mischief”—finds that they have invaded his library, and upset everything. He is, however, equal to the situation and doesn’t “suffer the sun to go down upon his wrath,” feeling “all the better for keeping close to the Scripture precept.”

In the January 1862 issue of Merry’s Museum, “Uncle William” was introduced to the

“Merry

Cousins”: “But who’s this entering the sanctum without

knocking, just as if he were at home? Much joy to you, boys and girls, for

we recognize an old friend, both to you and Uncle Merry.” The “old friend”

was William A. Fitch, who

thus joined the editorial staff. Cropped of its playing children, the

illustration helped to emphasize the sense that the column was a physical

place where the editors and the subscribers met for conversation.

Harper’s Weekly included a lovely engraving of a carte de visite

available from the National Freedman’s Relief Association, in its January

30, 1864 issue, with the

stories of the people pictured. The image is

similar to “Emancipated Slaves,” photographed by M. H. Kimball, which is

reproduced in Young America: Childhood in 19th-Century Art and Culture, by Claire Perry (p. 100).

[Other examples]