So many kids love dinosaurs that it’s difficult to remember that there

weren’t always dinosaurs for them to love.

So many kids love dinosaurs that it’s difficult to remember that there

weren’t always dinosaurs for them to love.

“ ‘A Former State of This Earth’: Fossils in Early American Works for

Children” is a

brief introduction

to works on fossils published for American children in books and magazines

from 1802 to 1853. Some are illustrated; many aren’t. Many of the

illustrations, as with much of the text, are

redrawn from earlier works.

Nathaniel Dwight’s A Short But Comprehensive System of the Geography of

the World (1802) includes mention of the

fossils at Big Bone Lick, but

no real assurance that the mammoth was extinct.

Ezra Sampson mingles fact with folklore in Youth’s Companion; or An

Historical Dictionary (1813), a collection of paragraphs on everything from

William Herschell to cannabis; his tangle of information on the

mammoth includes speculation

that its bones were scattered from Siberia to North America by the Deluge.

Taking the bible as a source of historical information, the author of

Blair’s Outlines of Chronology

(1825) presents the then-standard explanation that the earth was created

in 6 literal days about 6,000 literal years ago and that the Deluge was an

historical event, since “the earth bears visible marks of having experienced

some great convulsion.”

In “Petrified Forests” (1832),

the Juvenile Rambler

describes transformed forests near Rome and near Yellowstone, though the

author doesn’t attempt to place them in the geological chronology.

Parley’s Magazine often

explored the worlds of history and science;

“Fossil Shells” (1834) is a filler

pointing out that a rock layer found in France could also be found high

in the Andes, though there’s no attempt to explain how this was possible.

Evidently reprinted from a British work,

“The Fireside” (1839) describes

coal and the history of its use, explaining to readers of

Parley’s Magazine that it

is the remains of vegetation uprooted by the Deluge.

While mastodons had been discovered well before 1839,

“The Mastodon” is probably the first

description of it published for American children—though “description”

doesn’t mean that readers of the

Youth’s Cabinet would

understand what the animal looked like.

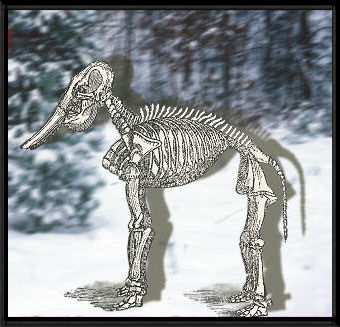

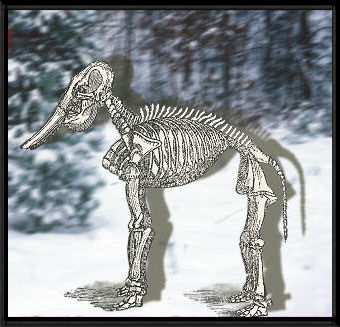

Robert Merry’s Museum

offers young readers an articulated mastodon skeleton and a detailed

description, in

“The Mammoth” (1841). The piece served

to introduce a fuller discussion of fossils to appear later.

Josiah Holbrook gives geology its due in

“Organic Remains” (1841), which

includes illustrations of a megatherium skeleton and explains that

animals become extinct, “to give place to other and different races, each

succeeding race being fitted to the state of the earth at the time they

inhabited it.”

Probably the first dinosaur illustrations in an American periodical for children appear in

Robert Merry’s Museum in 1842,

though the word “dinosaur” isn’t used to describe the iguanodon, the

plesiosaur, or the ichthyosaur;

“Wonders of Geology” incorporates

material from several sources.

The well-illustrated The Wonders of Geology

(1845) examines the fossil record in detail, acknowledges that the

Earth is unimaginably old, and concludes that geology proves that the

biblical story of creation is correct.

The editor of

The Young

People’s Mirror presents readers with a long list of the types of

creatures found in fossil form, in

“Geology” (1849); implied is that the

creatures were exactly the same as modern versions.

The Schoolmate

recreates fossil creatures like the megatherium, the plesiosaur,

and the dinotherium in words and illustrations in

“Wonders of Geology” (1852).

Just as the prehistoric world was remade for humans, readers are assured, so

will it be recreated again after Judgment.

In 1853, “Professor Pickaxe” explores the history of the Earth and the

variety of prehistoric life in the seven-part

“Letters About Geology”; geology proves

that the earth was created in 6 of “God’s days” untold ages ago. The

Deluge isn’t mentioned.

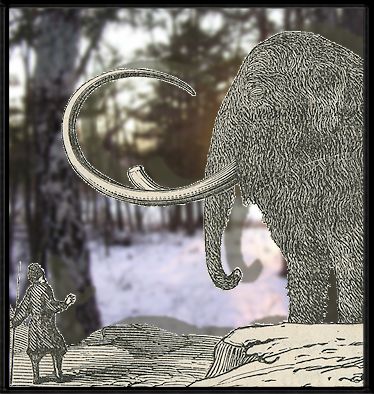

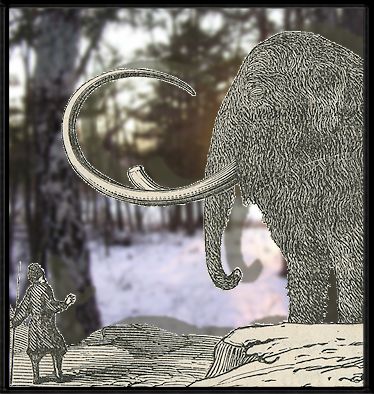

The mammoth’s bones had been clothed in illustrations by 1871, when

“The Mammoth” detailed an exciting

find by a Siberian hunter many years earlier.

“Uncle Jacob” discusses the investigation of creatures who lived

“many ages, perhaps, before the creation of man” in

“The Ancient World (1872),

accompanying an illustration based on Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’s sculptures

of labyrinthodons, pterosaurs, iguanodons, and other dinosaurs

in London’s Crystal Park.

Some good reading:

- Martin J. S. Rudwick. Scenes from Deep Time: Early Pictorial

Representations of the Prehistoric World. Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 1992.

- Jane P. Davidson. A History of Paleontology Illustration.

Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2008.

- Paul Semonin. American Monster: How the Nation’s First Prehistoric

Creature Became a Symbol of National Identity. New York: New York

University Press, 2000.

- Stanley Hedeen. Big Bone Lick: The Cradle of American Paleontology.

Np: The University Press of Kentucky, 2008.

- Dennis R. Dean. Gideon Mantell and the Discovery of

Dinosaurs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Adrienne Mayor. The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and

Roman Times. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Simon Winchester. The Map That Changed the World: William

Smith and the Birth of Modern Geology. New York: HarperCollins, 2001.

So many kids love dinosaurs that it’s difficult to remember that there

weren’t always dinosaurs for them to love.

So many kids love dinosaurs that it’s difficult to remember that there

weren’t always dinosaurs for them to love.