“Among The Studios,” number 3, by T. B. Aldrich (from Our Young Folks; July 1866, pp. 393-398)

There are certain streets, or parts of streets, in London, which are entirely occupied by booksellers, printers, binders, engravers, &c., &c. There is a seedy row of shops in New York wholly given over to unregenerate dealers in second-hand clothing. In some streets the drug-store has almost become an epidemic: these latter localities are greatly affected by the undertakers, and are always contiguous to some quiet avenue broken out all over with little gilt tin signs bearing the names of doctors, and di-

-----

p. 394

recting the afflicted public to “Ring the night-bell.” Trades of a feather, like the birds, are fond of flocking together, and have a habit of lighting on particular spots without any particular reason for so doing.

Our friends, the artists, possess the same social tendencies, and, in the selection of their studios, often display the same eccentricity. We shall never be able to understand why eight or ten of these pleasant fellows have located themselves in the New York University. *

There is n’t a more gloomy structure outside of one of Mrs. Radcliffe’s romances; and we hold that few men could pass a week in those lugubrious chambers without adding a morbid streak to their natures,—the present genial inmates to the contrary notwithstanding.

There is something human in the changes that come over houses. Many of them keep up their respectability for a long period, and ripen gradually into a cheery, dignified old age; even if they become dilapidated and threadbare, you see at once that they are gentlemen, in spite of their shabby coats. Other buildings appear to suffer disappointments in life, and grow saturnine, and, if they happen to be the scene of some tragedy, they seem never to forget it. Something about them tells you,

“As plain as whisper in the ear,

The place is haunted.”

* The following artists occupy studios in the New York University: Eastman Johnson, A. Fredericks, W. J. Hennessy, Eugene Benson, Edwin White, Marcus Waterman, C. G. Thompson, Winslow Homer (the subject of our present paper), A. J. Davis, and J. A. Howe.

-----

p. 395

The University is one of those buildings that have lost their enthusiasm. It is dingy and despondent, and does n’t care. It lifts its machicolated turrets of whity-brown marble above the tree-tops of Washington Parade-Ground with an air of forlorn indifference. Summer or winter, fog, snow, or sunshine,—they are all one to this dreary old pile. It ought to be a cheerful place, just as some morose people ought to be light-hearted, having everything to render them so. The edifice faces a beautiful park, full of fine old trees, and enlivened by one coffee-colored squirrel, who generously makes himself visible for nearly half an hour once every summer. As we write, his advent is anxiously expected, the fountain is singing a silvery prelude, and the blossoms are flaunting themselves under the very nose, if we may say it, of the University. But it refuses to be merry, looming up there stiff and repellent, with the soft spring gales fanning its weather-beaten turrets,—an architectural example of ingratitude.

Mr. Longfellow says that

“All houses wherein men have lived and died

Are haunted houses.”

In one of those same turrets, many years ago, a young artist grew very weary of this life. Perhaps his melancholy spirit still pervades the dusty chambers, goes wearily up and down the badly-lighted staircases, as he used to do in the flesh. If so, that is what chills us as we pass through the long, uncarpeted halls leading to the little nookery tenanted by Mr. Winslow Homer.

The reader should understand that the University is not, like the Tenth Street Studio Building, monopolized by artists. The ground-floor is used for a variety of purposes. We have an ill-defined idea that there is a classical school located somewhere on the premises, for we have now and then met files of spectral little boys, with tattered Latin grammars under their arms, gliding stealthily out of the sombre doorway and disappearing in the sunshine. Several theological and scientific societies have their meetings here, and a literary club sometimes holds forth up stairs in a spacious lecture-room. Excepting the studios there is little to interest us, unless it be the locked apartment in which a whimsicle virtuoso has stored a great quantity of curiosities, which he brought from Europe, years ago, and has since left to the mercy of the rats and moths. * This mysterious room is turned to very good dramatic account by the late Theodore Winthrop, in his romance of “Cecil Dreeme.”

It has taken us some time to reach Mr. Homer’s atelier, for it is on the third of fourth floor. But the half-finished picture on his easel, the two or three crayon sketches on the walls, (military subjects,) and the splendid view from his one window, cause us to forget that last long flight of stairs.

The studio itself does not demand particular notice. It is remarkable for nothing but its contracted dimensions: it seems altogether too small for a man to have a large idea in. If Mr. Homer were to paint a big battle-piece, he would be in as awkward a predicament as was the amiable Dr. Primrose.

* A friend informs us that this “antiquary’s collection” has been removed within a year or two.

-----

p. 396

when he had the portraits of all his family painted on one canvas. “The picture,” says the good old Vicar of Wakefield, “instead of gratifying our vanity, as we hoped, leaned, in a mortifying manner, against the kitchen- wall, where the canvas was stretched and painted, much too large to be got through any of the doors.”

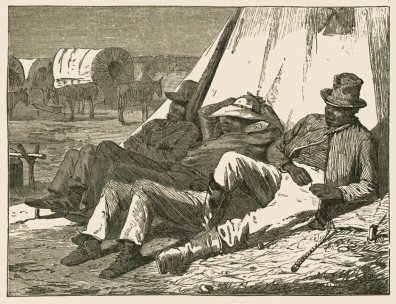

It is only a few years since Mr. Homer’s name became known to the public. He is the youngest among the men to whom we look for a high order of excellence in the treatment of purely American subjects. Mr. Homer served his apprenticeship as draughtsman for several illustrated periodicals, learning to draw before he plunged into colors, as more impatient aspirants usually do. The back numbers of the pictorial weeklies furnish innumerable evidences of his industry and progress. A better school of instruction could not have been devised for him. shortly after the beginning of the war, Mr. Homer went to Virginia, and followed for a while the fortunes of the Army of the Potomac, contributing, from time to time, spirited war-sketches to the pages of a New York illustrated journal. He returned North with a year’s experience of camp-life and a portfolio of valuable studies. From these studies he has since painted his most successful pictures. Mr. Homer is very skilful in the delineation of negro characteristics. The engraving which we print on this page, copied by the artist from the original painting en-

titled “The Bright Side,” seems to us in his best manner. Of course the broad effect of sunlight attained by oil-colors cannot be reproduced in a wood-cut. Three picturesque-looking Contrabands, loving the sunshine as bees love honey, have stretched themselves out on the warm side of a tent, and, with their ragged hats slouched over their brows, are taking “solid comfort.” Something to eat, nothing to do, and plenty of sunshine constitute a

-----

p. 397

Contraband’s Paradise. The scene is one that was common enough in our camps down South during the war; but the art with which it is painted is not so common.

While Mr. Homer was engaged on this canvas, he suddenly found himself in want of a model for one of the figures. In Italy or France there are men and women who earn their livelihood by serving as models for the painters; but this class does not flourish very well in our country, and Mr. Homer was somewhat puzzled as to how he should find his man. In one of the cross-streets near the University lives a colored person whom we shall call Mr. Bones,—if we were to use his real name he might resent it as a liberty. Mr. Bones (formerly) “belonged to one of the first families of Virginia,” but when the Rebellion broke out he selected New York as his residence, and, at the time of which we are writing, was engaged in the lucrative profession of bootblack,—a profession of which he is still a shining ornament.

It occurred to our artist, that Mr. Bones would serve his purpose excellently well. One morning, as Mr. Bones was passing the University on his usual tour in search of customers, he was accosted by the painter, who explained his artistic wants. But Mr. Bones was proof against the most lucid explanation. If Mr. Bones’s head had been iron-clad, it could n’t have resisted a new idea more successfully. He was at length induced to enter the University, and, after great trouble,—Mr. Bones at the foot of each stairway evincing a desire to run away,—was finally conducted to the artist’s studio. In order that his prize might not escape him, the painter quietly locked the door. No sooner did Mr. Bones perceive this movement than he gave vent to a series of unearthly shrieks, and proceeded to roll himself up into a ball, much after the fashion of a sow-bug,—a cunning little creature, that can, at will, make itself look for all the world just like large-sized buckshot.

Mr. Bones bounced round the narrow apartment so furiously, and continued to shriek so lustily, that the astonished painter made haste to throw open the door. Mr. Bones instantly ricocheted over the threshold like a huge cannon-ball, and ws heard bounding down stairs, five steps at a time.

The cause of this singular conduct on the part of Mr. Bones was afterwards accounted for. It appears the simple fellow had somehow conceived the idea that the artist was “a medicine-man,” (i. e. an army-surgeon,) and that he had lured him, Mr. Bones, into his den for the purpose of relieving the said Mr. Bones of a limb or two, by the way of practice. This is one solution of our friend’s terror. Our own impression is, however, that the profound gloom of the University turned his brain.

In spite of this mischance, “The Bright Side” was finished, the artist being fortunate enough to obtain a less refractory model.

We think it was in 1863 that Mr. Homer received his first general recognition as a painter. In that year he contributed to the thirty-eighth annual exhibition of the National Academy of Design two small pictures, which attracted considerable attention, and were at once purchased by a well-known connoisseur. It was our good fortune to be among the many who saw in

-----

p. 398

these paintings, not only a promise of future excellence, but an excellence accomplished. In an old memorandum-book, kept in those days, is the following note, which we beg leave to transcribe.

“Two little war-scenes (Nos. 255 and 371), by Winslow Homer,—his first appearance in any academy. Mr. Homer calls his pictures ‘The Last Goose at Yorktown,’ and ‘Home, Sweet Home.’ The former represents a couple of Union boys cautiously approaching, on all fours, an overturned barrel, out of the farther end of which the wary goose is observed making a Banks-like retreat. A neat bit of humor, Mr. Homer. The second picture shows a federal camp at supper-time. The band in the distance is supposed to be playing ‘Home, Sweet Home’; in the immediate foreground are two of the boys, one warming the coffee at the camp-fire, and the other dreamily watching the operation; but his heart is ‘over the hills and far away,’ for the suggestive music of the band has filled his eyes with visions of home. The different sentiments of the two incidents are worked out with gracious skill. The figures are full of character, but a trifle fresh in color, as is also the landscape.”

Mr. Homer has greatly improved on his first war-pictures, admirable as they were, and has given us several careful works on more peaceful subjects than Zouaves and cavalry charges. Yet we think his transcripts of camp-life, the battle-field, and the bivouac are the best exponents of his strength. It is to be hoped that his portfolio and his memory will afford him themes for many a noble picture illustrative of the most desperate struggle that the good knight Freedom ever had with the Prince of Darkness.