“The Chinese in California,” by Lucy St. John (from Robert Merry’s Museum, February, 1870; pp. 69-71)

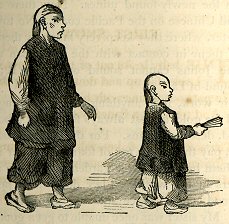

Boys, how should you like to wear such baggy clothes as this boy has on, and have your hair all shaved excepting a bit at the top of your head, pulled and braided to hang down in a tail behind, and be called See Hop, or Ah Wy, or Hop Chang, or Wee Ling? Instead of papa, with overcoat and shining beaver, what would you say, now, to such a father as this John Chinaman, shuffling along behind the small Johnnie?

I don’t believe you’d change places, or papas, though I’ve no doubt that this youngster, as he runs about the streets of San Francisco, is happy enough in his way; yet you, I think, are vastly better off.

There are not many Chinese children in California, for it is very seldom that a Chinaman brings his wife and family from the Celestial country; but they often take “secondary wives,” so that there are some families.

When the story of gold found on the Pacific shores reached China, the sleepy-looking Celestials were as wide awake about it as any nation under heaven. They had been pent within the walls of their own kingdom for ages, grovelling on as their dead fore-fathers had done; but now they were all agog, and in the streets of their chief cities were placards, with “Ho for the Golden Mountains!” in great Chinese letters, upon them.

The largest emigration took place in 1852, when twenty thousand John Chinamen flocked to California for their share of

-----

p. 70

treasure from the newly-found mines. Now there are more than sixty thousand Chinese on the Pacific coast. No town but has its Chinese quarter, where they keep very much by themselves, unless work brings them in contact with the “Melican man,” as they call us. The Johns cannot sound our letter R; they always give it the sound of L.

As for their work, it is anything and everything. Thousands wash the soil for gold, almost always following other miners, and delving in old, deserted claims. For the privilege of mining, they, as foreigners, pay the state a tax of four dollars per month.

Many of them have vegetable gardens; and they are among the best gardeners in the world. They do general housework, and they make good cooks. Once showing them how to do a thing is sufficient. My sister was once unable to get a good Irish servant, and took into her service Ah Sam, a Chinaman, who did very well when he was so carefully watched that he could not steal everything he laid his hands upon,—as he would have been glad to do,—and who especially excelled in washing and ironing. The linen looked lovely when it came from his hands; but to my sister’s dismay, she once caught him sprinkling the clothes by squirting the water over them from between his teeth. This, however, was not so bad as our neighbor’s How Chee; for he was discovered moistening the tops of loaves of bread ready for the oven in the same appetizing manner.

All the Chinese on the Pacific coast belong to one of six companies. These companies are organized for the purpose of protecting the members, helping them to get work, and—what they are very anxious about—seeing that their dead bodies are taken to China for burial. It is said that some of the ships sailing to China take home as many dead as living Chinese.

They bury their dead, temporarily, in California ground; and they are sure to scatter bits of white paper from the house to the grave, that the spirit may find its way back to its earthly home. At the grave they roast a pig, which they carry home to eat at the funeral supper.

The great mass of Chinese in California live in low, dark houses, filled as full as they can be crowded; and the Chinese quarter of any town is by no means the most delightful for a walk.

The traits of Johnny’s character are not often beautiful or generous; he is a great coward, afraid of every dog that he meets; he will tell lies very fast, and steal sometimes as fast; and yet—poor

-----

p. 71

old yellow boy in baggy clothes and trailing pig-tail—he has some positive virtues; he is charitable among his own people, quiet enough, not intemperate, and he reverences old age as few others do. Do think how he has been shut up in that old kingdom of China for ages, growing tea for all the old ladies in the world to drink, and making silk for all the younger ones to wear; and is it strange that he cannot make a sudden plunge into a new land without “both looking and feeling queer”?

I always pitied him, to be treated so shamefully as he is in California—nicknamed, cheated, robbed, kicked, and hooted at. A patient old creature under all this abuse, too, is John; he seldom asserts his rights, but jogs along, glad to get a living any way that he can.

Sometimes the Chinaman gets the best of it. I knew a jolly young man, who, without a bit of ill will towards Johnny, loved dearly to poke fun at him; he was accustomed to greet the strange Johnnies who got out of the cars or stages, at the Folsom depot, with this salutation: “John, how’s your grandmother?” to see the vacant, helpless stare the poor fellows would give on being questioned in unknown words. One morning, when the train arrived from Sacramento, a Celestial stepped out, and my friend greeted him as usual: “John, how’s your grandmother this morning?” The Chinaman looked him steadily in the face, and in good English replied, “She’s very well, thank you—how’s yours?” I believe the young man never put this question again to a Johnny, and the laugh of the bystanders was louder than ever.

One can hardly help laughing at the strange race, they seem such a queer sort of patch in the mottled quilt of California life. They do everything in such a comical way! They never walk, but jog; they never run, but trot. If they ride horseback, as they are fond of doing, they sit so near the horse’s tail, they are in constant danger of going off behind. When they wish to rest in their journeys afoot, they squat down, three or four often in a row, in the most ridiculous attitude imaginable.

Queer as they are, they have built for us the great Pacific Railway. We want work done, and they are willing and eager to do it; and I don’t see why they should not be suffered to remain with us, protected, so long as they mind peaceably their own business, and given equal rights with the Irish, or any other foreigner who seeks America as the home of all the world.