-----

[cover p. 2; inside front cover]

Whatever brawls disturb the street,

There should be peace at home;

Where sisters dwell, and brothers meet,

Quarrels should never come.

Birds in their little nests agree,

And ’tis a shameful sight,

When children of one family

Fall out, and chide, and fight.

Hard names at first and threat’ning words,

That are but noisy breath,

May grow to clubs and naked swords,

To murder and to death.

The devil tempts one mother’s son

To rage against another;

So wicked Cain was hurried on,

’Till he had kill’d his brother.

The wise will make their anger cool,

At least before ’tis night;

But in the bosom of a fool,

It burns till morning light.

Pardon, O Lord! our childish rage,

Our little brawls remove;

That as we grow to riper age,

Our hearts may all be love.

-----

p. 1; p. 17

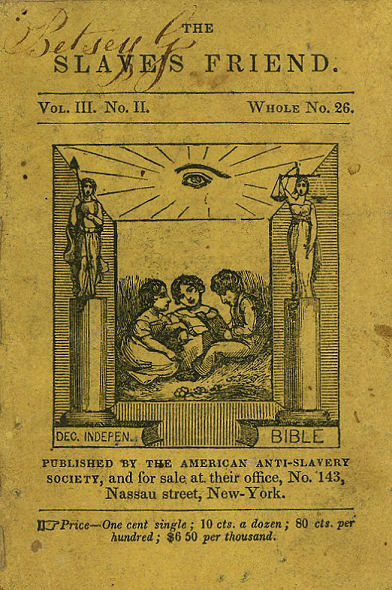

SLAVE’S FRIEND.

-----

Vol. III. No. II. Whole No. 26.

BOWIE KNIFE.

These horrid weapons are usually called Bowie knives. They were invented by a man who lived in the state of Louisiana. His name was Buie. It is a French name, and is pronounced Bóo-e. Afterwards he went to Texas, and was killed there in battle.

People in slave states often carry such knives about them. When they get angry they draw the knife, and sometimes stab one another!

A man who keeps a shop in Broadway, New York city, sells Bowie knives.

-----

p. 2; p. 18

Several people in New York sell them. I saw one at his window. It had two words on the blade, etched in, as they call it. Perhaps you have seen razors with mottoes on the blade, in the same style. Do you want to know what the words were on the blade? I will tell you—“DEATH TO ABOLITION.” I asked the man a great many questions about these knives. He said they were imported from England by several merchants in this city. He told me the names of two of them. One keeps his store in Pearl Street, and the other in Maiden Lane.

The man said also that Bowie knives are made at Newark, New Jersey, and Springfield, Massachusetts, but he never saw any with the words, “death to abolition,” on them, except those imported from England. But one seller said he could have the words put on here if purchasers wished it. How wicked to make such knives! How wicked to sell them!! How wicked to use them!!!

-----

p. 3; p. 19

About a year ago there was an exhibition of the deaf, and dumb, and blind children, at the Chatham Street Chapel.

Several little deaf and dumb children wrote down what was said to them. They also talked to each other. You may think it very strange that children who could not hear should write, and those who could not speak, should talk. But they did not talk as we do. They made signs with their fingers, so that they understood each other.

The blind children also read, and very well too! This, you will say, was very strange indeed—“I never heard of blind people reading.” Do you say so? Then listen. The way they read was this. They had books with the letters raised higher than the rest of the page, so that they could feel them. After they had been taught the difference between different letters, and

-----

p. 4; p. 20

learned their names, they could read quite well.

You are not deaf, nor dumb, nor blind. You can learn to read, and write, much easier than the dear children I have been telling you about. Be thankful, then. God has been very kind to you. Pity those poor children. But there are other children you ought to pity much more. I mean the poor little slaves. They have eyes, and ears, and fingers, and would learn to read and write as fast as you if they were permitted to do so.

But it is against the law, in slave states, to teach them to read and write! They have not privileges equal to our deaf, and dumb, and blind children. The slaveholders keep their minds in darkness. God meant that they should learn to read, and read the Bible, but the slaveholder says NO, you shall not learn to read nor write. They whip any one the first time he dares to teach them, and the next time they hang him!

-----

p. 5; p. 21

I am going to tell you about a little slave in the East Indies. She was born in Burmah. Her name was Meh Shway-ee. Several years ago she was a slave at Amherst, British Martaban. She had a cruel master. He beat her so that one of her arms was broken, and her body was covered with scars.

Once, when he was whipping her, she cried so dreadfully that her master thought some one would hear her. So he shut her up in a secret room, and told people she was very sick, and perhaps would die. Some American missionaries lived at Amherst, and they heard of it. They tried hard to get the cruel master to give up the little girl, and at last succeeded.

They took her to the mission house. She was very pale and thin. She had suffered a great deal of pain, and was almost starved. She cried for several days and nights a great deal. But they dressed her wounds and gave her food,

-----

p. 6; p. 22

and treated her kindly. So she got well at last. Then they put her in the native female school.

When the government knew of this affair, her cruel master was taken up, and put into prison for several months. At last he had his trail, and was sentenced to be kept in prison four years, in irons, and to labor in the public works. His confinement broke down his spirits, and he contrived to get some poison and killed himself. His guilty soul went to eternity, to be tried at the bar of God.

After Meh Shway-ee joined the school she had pretty good health for about six months. Then she was taken ill, and died.

Rest, little slave, thy work is done,

The cross is past, the crown is won:

Rest, suffering child, on Canaan’s shore,

Where pain is felt and fear’d no more.

Thy story tell to saints on high,

And sound His praises through the sky,

Who rescued thee from tortures dread,

And pour’d salvation on thy head.

-----

p. 7; p. 23

Rest, sainted seraph, on thy throne;

The bliss of Heaven is now thine own;

Move in thy sphere, a beauteous star,

And shine on us, thy friends, afar.

For thou art not on earth forgot,

And when our bodies press this spot,

We hope, in heaven, again to see

The ransom’d slave girl, Meh Shway-ee.

Slaves, in this country, are as much abused as the little Burman slave was. But no kind missionary is allowed to “deliver them out of the hand of the oppressor.” And who ever heard of an Americn slaveholder being sent to a state-prison because he was cruel to his slaves?

[For the Slave’s Friend.]

TO JUVENILE ANTI-SLAVERY SOCIETIES.

Dear Young Friends,—A committee was appointed by the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, in May last, in this city, to write to you. That convention consisted of many of your mothers and sisters, and they met to converse about their duties as anti-

-----

p. 8; p. 24

slavery women, and as friends of their free colored brethren and sisters.

They heard, with much pleasure, that many of you feel for the poor slaves, and are trying to do something for them. Sometime ago many persons thought you could not understand much about slavery, or do any thing to put an end to it; and some people think so even now.

A few months ago, two gentlemen were travelling in a stage coach. One was a slaveholder and the other an abolitionist. The abolitionist gave the slaveholder some anti-slavery pamphlets to read. One of them was a Slave’s Friend. The slaveholder turned over the leaves, looked at the pictures, and read some of the stories. He then said, “now I begin to fear. If you make children abolitionists slavery must come to an end.”

Yes, dear young friends, the slaveholder spoke the truth. Slavery will come to an end if the children read, talk, and act about it. You may have

-----

p. 9; p. 25

some influence with your parents, and persons who are older than you. We will tell you a few things that you can do.

Ask your friends to read the anti-slavery publications. Tell them what you have read about slavery. Let them see that you feel for the poor slaves and the free people of color. Try to learn more about slavery. The more you learn about it the more you will feel. And the more you feel on the subject, the more useful you can be. Be very kind to colored people. Treat them as well as you do white people. Above all, pray for colored people, whether bond or free.

When you hear the “sabbath bell” think that there are hundreds of thousands of little children, in the slave states, who never go to the house of prayer. They do not hear about a Saviour as you do. When you sit by your mother’s side, or go hand in hand with your brothers and sisters to school, remember the little slaves. They are

-----

p. 10; p. 26

very often sold and taken away from their dear parents. In many states it is against the law to teach them to read. While you are playing so happily they are working hard in a hot sun, or are driven about by their young masters.

Remember, too, that in the free states the colored children are very often ill-treated. How would you feel if the schools, and museum, and many other places where you love to go, were shut against you? If you were called hard names, or laughed at, by wicked people as you went along the streets? Yet colored children suffer all this and a great deal more.

Now you can do much to make them happy if you will act towards them as you would wish others to do to you, if you were colored. This would be keeping the “golden rule,” you know.

Ah! while we are richly blest,

They are wretched and distrest;

Outcasts in their native land,

Crush’d beneath oppression’s hand,

-----

p. 11; p. 27

Scarcely knowing even Thee,

Mighty Lord of earth and sea!

Do you ever think when you are using sugar, rice and cotton, that the poor slaves work very hard to get these things for the white people? Day after day and year after year, they work in the swamps, and in the fields, without any wages. Now if you eat or wear slave-labor produce do you not encourage slavery? Are you not, therefore, willing to do without sugar, rice, molasses, and other articles, that are produced by slave-labor? There is a plenty of sugars, &c., from places where free people work to raise them without fear of the whip and the chain. When asked to use slave-labor produce you can say with E. M. Chandler,

And ’tis because of all this sin, my mother, that I shun

To taste the tempting sweets, for which such wickedness is done.

If men to men will be unjust, if slavery must be,

Mother the chain must not be worn, the scourge be plied, for me.

-----

p. 12; p. 28

Sarah M. Grimké, and her sister, Angelina E. Grimké, were at a meeting of children, in Boston, last June, and told them a very pretty story about a little African girl. “Dear children,” said Sarah, “when I was a little girl, I had a present. A little girl was bought out of a slave-ship, and given to me for my slave!

“The poor little orphan child was frightened at the sight of white people. She would not eat, and was very thin and poor. I asked her why she did not eat and grow fat? She said she was afraid if she ate and grew fat, the white people would kill and eat her.”

“When she saw the cook carving with his knife, she would tremble all over, thinking he was going to kill and eat her. She told me her mother was a princess in Africa; that one day she went out a great way from her mother,

-----

p. 13; p. 29

and some white men sprung out from the bushes, threatened to kill her if she cried, and carried her to a ship, and brought her away, and she had never heard from her mother since.

“I can but weep,” said Sarah M. Grimké, “to think of this dear child! How much she used to suffer, thinking about her dear mother and her pleasant house in Africa, and about the cruel white people. I treated her kindly, and she died when she was 18. But never, dear children, can I love the slaves enough, and do enough for them.”

The children, and all who were present, were moved to tears. Angelina arose to speak, but she could hardly utter a word, she was so overcome to think how the poor slaves have to suffer. She told the children what she had seen of slavery, and how they are treated. As she has always lived in a slave state she knows all about it.

Sarah told the children she had seen

-----

p. 14; p. 30

twenty children chained together, and driven through the streets of Charleston, S. C. to be sold in New Orleans, never more to see their parents. As they went along the driver would whip them.

Joseph Horace Kimball was at the meeting. He has lately returned from the West Indies, and he told the children that it was safe there to give the slaves their freedom immediately. If safe there it would be here.

A collection was then taken up, as there should be at every anti-slavery meeting; the Slave’s Friend was given to the children; and the meeting was dismissed.

GOD’S CHILDREN.

Little Mary is four years old. One Sabbath her papa had her baptized. The next day I called at her father’s house. Mary came to me, and we talked together sometime. [sic] I asked her a great

-----

p. 15; p. 31

many questions; and she answered them. Among others were the following:

“Mary, whose daughter are you?”

“I am God’s little daughter.”

“What makes you think so?”

“Because papa gave me away to God yesterday.”

“Why did your papa give you away to God?”

“Because papa says I belong to God, and am his child.”

“Do all little children belong to God?”

“Yes, sir, for God made them.”

“Who are they that steal little children from God, and hold, and use them as property?”

“Slaveholders.”

“What does the Bible call them?”

“Men-stealers.”

“Why?”

“Because they steal God’s little children, and sell them.”

“Yes. Slaveholders do steal God’s little children. They will not let the children read any thing about their

-----

p. 16; p. 32

heavenly Father. Yet some of them pretend to love God, while they rob him of his children.”

“How can slaveholders love God, while they rob him of his children, and treat them so?”

“They deceive themselves when they say they love him. Slaveholders do not tell the truth if they say they love God, while they hate little children and make them slaves.”

Little Mary prays for the slaves and for their oppressors. One day she said to her mamma;—

“Ma, I want to go and pray for the slaves.”

“Well, my dear, you may go.”

Soon after, the same day, she said “ma, I want to pray for Mr. Wright, the children’s agent.” So she went and prayed for the children’s agent. Let us all pray for him, that God will give him the spirit of Christ.

-----

[cover p. 3; inside back cover]

A little colored child was asked this question, “What is abolition?” He gave this answer—“It is being good to colored people.” Dear reader! If you call yourself an abolitionist be kind to colored people. If you are not God will call you a hypocrite!

THE SUM OF THE COMMANDMENTS;

Out of the New Testament.

Matthew xxii, 37.

With all thy soul love God above,

And as thyself thy neighbor love.

EXODUS, CHAPTER XX.

1. Thou shalt have no more Gods but me.

2. Before no idol bow thy knee.

3. Take not the name of God in vain.

4. Nor dare the Sabbath-day profane.

5. Give both thy parents honor due.

6. Take heed that thou no murder do.

7. Abstain from words and deeds unclean.

8. Nor steal, though thou art poor and mean.

9. Nor make a wilful lie, nor love it.

10. What is thy neighbor’s, dare not covet.

-----

[cover p. 4; back cover]

Bowie Knife, … 1

The Deaf, and Dumb, and Blind, … 3

The Burman Slave Girl, … 5

To Juvenile Anti-Slavery Societies, … 7

Juvenile Anti-Slavery Meeting, … 12

God’s Children, … 14

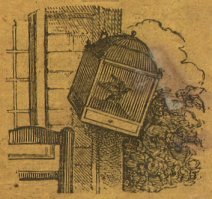

THE STARLING.

[“]I can’t get out, I can’t get out,” said the starling.